Georges Clemenceau, a notable French politician (1841-1929), was apt as he said, “War is too serious a matter to entrust to military men.” But in the case of the Russia-Ukraine war, it seems it is politicians at large who are failing in reading the bigger picture of peace and security, as the erstwhile bloc politics is once again pushing the world at the brink of a catastrophic World War-III.

Russia has risen too fast and is a power to be reckoned with. Under the leadership of the Czar, President Vladimir Putin, the Kremlin is challenging the world order, and since February 2022 when Moscow invaded its western neighbour, Ukraine, the so-called bipolarity has come to an end.

The globe and politics are in a non-polarity transition phase, and the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war will go a long way to define which tactical weapons are used, what is the role of Artificial Intelligence, especially the use of drone and surveillance systems, as well as the role of natural resources that shape the responses of neighbours, allies and adversaries when pitched in an environment of utter interdependence.

Moscow’s audacity to invade a smaller but literally powerful and resource-based neighbour, and get away with it as the United States and the democracy-preaching West harps to inaudible tunes is a theme of realpolitik in times to come.

The emerging new equation in the realms of geo-economics simply suggested that state-state security reigns supreme and no amount of extra-territorial assurance to safeguard one’s independence and sovereignty are fruitful, if confronted with an existential paradigm. Likewise, the neo-liberalism concept of interstate affairs of the 21st century that trade and commonality of interests can override enmity and ensure a level-playing field in times of confrontation proved to be quite hollow, as is the despicable case of Ukraine.

International guarantees to protect its integrity proved to be hollow, and one of the best trade and commerce connectivity failed in stopping an aggression. This 2022 war on Ukraine, the first interstate war since 1945, taught a cardinal lesson to smaller states across the world, and especially for South Asian minions, that self-reliance and self-insured security is a must. Ukraine by giving up its nuclear shield had committed a blunder, and Russia and the likes in the league of power can never be trusted come-what-may.

The new power-peg

We are breathing in a wayward world. It is now a foregone conclusion that the lone superpower, the United States of America, is struggling to keep its momentum in global affairs. Its leadership stands challenged, especially in the backdrop of a hurried exit from Afghanistan and now the war in Ukraine, where despite pumping in more than $14 billion of armament, the US and its allies are taking flak.

The rise of China, likewise, is a case in point. Beijing is undoubtedly emerging as the next biggest economy of the world, and coupled with its geo-strategic muscles is getting hard to be contested by Washington. By playing a discreet role in the Russo-Ukrainian war, China has taught a lesson to the Capitalist West. It went ahead to rope in economic benefits from Russia by importing cheap oil, and at the same time expressed its neutrality in the war, despite categorically supporting Moscow and understanding its qualified concerns relevant to its geographical exigency. Beijing has killed two birds with a single stone: won over Russia, and kept the US guessing by staying aloof from being a direct stakeholder in the war.

South Asia’s dilemma

The South Asian region, including Afghanistan, which directly stands impacted by the war in Ukraine has taken a stance that is unique, and marvels how national interests influence decision-making in dire straits. It goes without saying that the underdeveloped world i.e., South Asian, has drunk from a chalice of poison, as their respective economies have nosedived and they suffer from scarcity of energy and food supplies.

The fact that Kyiv and Moscow have dictated the new geo-economics terms and proved beyond doubt how important uninterrupted food and energy supply chains are is a lesson to be learnt for the West. The US and its allies had always relied on flimsy security conundrums by selling arms and ammunition, inventing power blocs, intoxicating allies with aid, and then leaving them in lurch when faced with adversities. Afghanistan and Pakistan being the Most-Allied-Allies are cases in point.

Thus, Russia is back on the canvas, and the last few years testify to the fact that its power and glory is shining. This makes it an interesting equation for the continent itself, as Asia is rapidly and surely outclassing the dominance of the Western hemisphere. Thus, an Asian Century is in the making, and Russia has led from the front in staging a comeback as a spent force to a remarkable entity in world affairs.

The impact is over-bound and is casting repercussions all over the continent. The international security compass is seeing new poles of power, as the unanimity between China and Russia is definitely outclassing the yesteryear American hegemony, especially in Southwest and South Asia.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China, which will go on to amalgamate around 60 countries in three continents in a nexus of trade and connectivity, has changed the entire paradigm of power politics. Russia too is never lost in the new equation of power-mongering as it has reconnected itself with many of the Asian states, especially the Central Asian Republics as well as European states in fomenting a new relationship, which is trade and investment oriented, and primarily caters to energy requirements. This is why we can say with confidence that Russia is the new power entrant on the Asian horizon and the emerging international order is in a state of flux.

The new change of order is witnessing a sea-change in economic ties, trade and investment. New logistical systems are emerging, and the connectivity pace has seen remarkable acceleration. This also corresponds to the Russian desire for laying new pipeline networks meant to supply oil and gas to the energy-starved countries of Europe, South Asia and elsewhere. This in itself is a shot in the arm for Russia’s military and political aspirations, and pitches it at the center-stage of power politics.

The momentum is evident as European states, despite nursing political and geo-strategic differences with the Kremlin, are moving towards Russia and are eager to trade in the spheres of energy. The year 2022 saw the turnover and the intensity of contacts increase dramatically. So is the case with India, Sri Lanka and many other South Asian countries. Pakistan too is interested in an energy corridor with Russia, and wants to import oil as well as edibles on a preferential basis.

The Asian Order

Asia is emerging on the horizon. The continent has conveniently replaced European dominance. The thrust is on social mobility and overcoming abject poverty. This in itself has created a new world order. The lifting up of 700 million people above the poverty line of poverty in China within 30 years, and the rise of Africa as a forward-looking continent are contemporary success stories.

This is why major powers of Asia are in a struggle of their own. They are struggling to create political and economic space for protecting their spheres of interest in the gradually slipping multipolar world. The manner in which South Asian states, including Pakistan, conducted themselves at the United Nations in abstaining from condemning Russia, and the uniting to call for Ukrainian territorial sovereignty manifests smart diplomacy.

Countries such as China, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and even Sri Lanka and Nepal believe in strong multilateralism as the way to go in foreign relations, as Russia sits pretty cool as the new magnet. This new amalgamation will usher in peace and stability in the Eurasian region, too.

Russian vibrancy and Pakistan

Russia sits on a portfolio of $14 billion regional gas infrastructure, and more than a dozen countries are beneficiary of it. Moscow has an edge in industrial collaboration, and there is a lot that Pakistan can gain from it. Any meaningful understanding with Russia comes as a win-win equation for Pakistan.

As Pakistan struggles with inflated oil and gas bills in the international market, the Russian option is seriously being studied. The desire on the part of Moscow to sell oil and wheat at subsidized rates is a welcome proposition. It is a source of strength and a shift in its foreign policy, and reflects that Pakistan wants to have a good working relationship with all the major powers, including Russia.

The flagship economic project between the two countries is the Stream Gas Pipeline. The 1,100 kilometers long pipeline from Karachi to Kasur has been longing for Russian expertise. The $2.5 billion Pakistan Steam Gas Pipeline project has been on the agenda since 2015. This coincides with CPEC’s first phase completion, and the initiation of the second phase which will see industrialization take roots.

In pursuit of energy, Pakistan is forging a long-term relationship with Russia. Former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s visit to Moscow underscored how important oil and gas are in state-centric relations. That reality lives on to this day, and despite the shenanigans of the 13 parties’ coalition government that they are uninterested in any such energy receipts, the truth rests somewhere else.

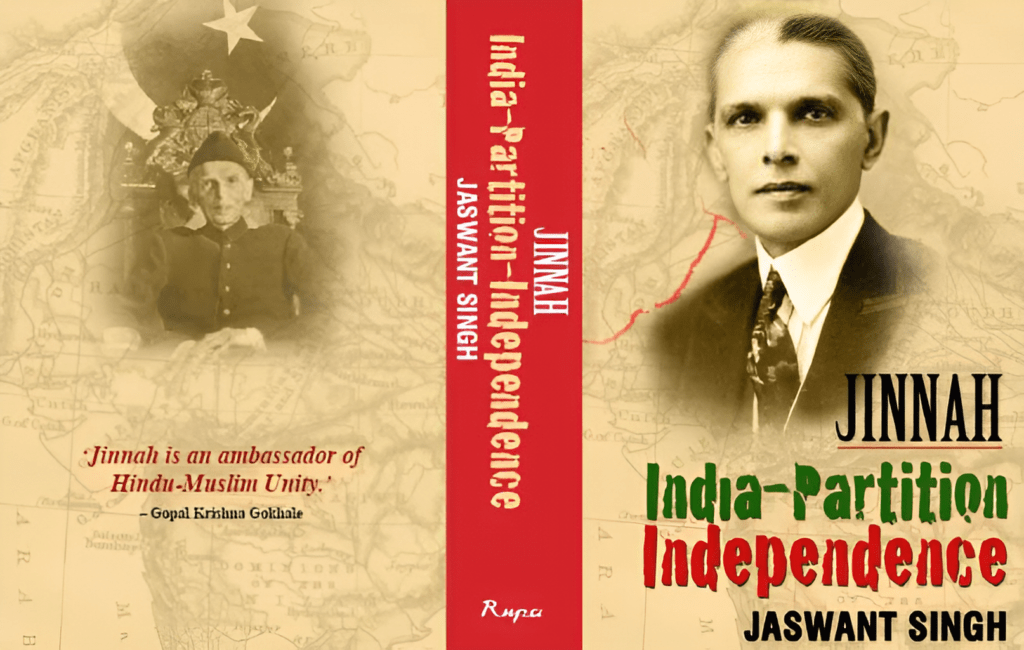

Former Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh, author of “Jinnah: India-Partition-Independence”, once quipped while talking to South Asian journalists in Delhi, where I was present too, in his poetic excellence, “QATL MAIDAN MEIN SIPAYI HONGE; AUR SURKH ROOH ZILL-E-ELAHI HONGE,” [Soldiers will embrace martyrdom on battlefield, whereas the credit shall be reaped by the sovereign emperor]. Sounds so true as President Putin builds a new order on the rubbles of minions’ destruction.