So tell the tale — perhaps they will reflect. [Koran 7:176]

The Word Islam

The Arabic word ‘Islam’ means “to turn oneself over to, to resign oneself, to submit.” In religious terminology it means submission or surrender to God, or to God’s will. The Koran uses the term and its derivatives in about seventy verses[1] but in only a few of these verses can we claim that the word refers exclusively to “Islam,” meaning thereby the religion established by the Koran and the Prophet Muhammad (Pbuh).

We have already seen that the Koran and the Hadith use the word din (religion) in a range of meanings. This is typical for many important terms employed in the Koran and the Islamic tradition. Incomprehension often occurs because people think they are talking about the same thing, whereas in fact they are merely using the same words. For example, when non-Muslims speak about Islam, they usually have in view the specific religion established by Muhammad (Pbuh). Muslims mean that religion too, but they frequently have one or more of the other meanings of the term in mind as well, and this tends to make mutual understanding difficult.

In the broadest sense, Islam means “submission to God” as an undeniable fact of existence. If God is understood as the only reality truly worthy of the name—or Reality with an uppercase R—then nothing else is truly real. In other words, everything else is dependent upon God for its reality. Or, to use less philosophical and more theological language, all things in the universe, and the universe itself, are creations of God. Since God made them the way they are, they depend totally upon God. Hence they are “submitted” to God.

In the first verse quoted below, a verse that we have already cited, this broadest sense of the term Islam is used to prove that true religion is established by God alone. The other verses illustrate the Koranic view that everything in the natural world praises and glorifies God. Simply by existing, all creatures demonstrate their Creator’s glory and perform acts that acknowledge God’s mastery over them:

What, do they desire another religion than God’s, while to Him has submitted whoso is in the heavens and the earth, willingly or unwillingly? (3:83)

Have you not seen how whatsoever is in the heavens and the earth glorifies God, and the birds spreading their wings? (24:41)

Have you not seen how to God bow all who are in the heavens and all who are in the earth, the sun and the moon, the stars and the mountains, the trees and the beasts, and many of mankind? (22:18).

Notice that “many of mankind” bow to God; this means, conversely, that many do not. Although from one point of view human beings are included in “the heavens and the earth” and hence are creatures of God and submitted to him, from another point of view they are free not to submit to him. This is the great mystery. It is here that human problems begin. People are not like mountains and trees, which simply submit to God’s will and give no thought to it. People are always faced with the fact of their freedom, the fact that they can choose to obey or disobey when someone tells them to do something, whether that someone be God, their parents, the government, or whoever. If there were no choices to be made, everything would be fine, because no one would be able to conceive of any other situation.

The book, “The Vision of Islam” by American Professor couple Dr. Sachiko Murata and Dr. Professor William C. Chittick [Shamas-ud-din Chittick] covers the four dimensions of Islam as outlined in the Hadith of Gabriel, practice, faith, Ihsan/spirituality, and the Islamic view of history. The excerpts from this popular simple, but interesting book are being presented here with his permission through a series of articles. The original language and words of the book have been kept as far as possible like the Koran for the Quran but supplications have been added with the name of Prophet (Pbuh) as per Muslim tradition of respect. Drawing on the Koran, the sayings of the Prophet (Pbuh) and the great authorities of the tradition, the text introduces the essentials of each dimension and then shows how it has been embodied in Islamic institutions throughout history. ‘The Vision of Islam’ is an introductory book, not the book of fiqh hence wherever the author has touched the matters related with the fiqh, the Muslim reader may follow the fiqh practiced by him/her.

The Koran says in the verse just cited that “many of mankind” bow to God. It frequently refers to these many as Muslims, that is, “those who have submitted to God.” Although “Muslim” normally means a follower of the religion established by the Koran, in the Koranic context it frequently means those who follow any of God’s Prophets. In translating the word in this sense we will employ the term muslim, rather than Muslim.

When [Abraham’s] Lord said to him, “Submit,” he said, “I have submitted to the Lord of the worlds.” (2:131)

Jacob said to his sons, “What will you worship after me?” They said, “We will worship your God and the God of your fathers, Abraham, Ishmael, and Isaac, one God, and we will be muslims a toward Him.” (2:133)

And when I revealed to the Apostles [of Jesus], “Have faith in Me and in My messenger,” they said, “We have faith, and we bear witness that we are muslims.” (5:111)

All prophets submitted themselves to God’s will and hence were muslims. In the same way, all those who follow the religions brought by the prophets are muslims. But clearly this does not mean that they follow the religion established by the Koran, which appeared in Arabia in the seventh century. Hence, in a still more specific sense, the word islam refers to the historical phenomenon that is the subject of this book, the religion that goes by the name “Islam.” Surprisingly, none of the eight Koranic verses that mention the word islam itself refers exclusively to this religion, since the wider Koranic context of the term is always in the background. It is probably true that most Muslims read these verses as referring to Islam rather than islam in a wider sense, but as soon as one understands the broad Koranic context, one can easily see that the verses have more than one meaning.

Religion in God’s view is the submission. (3:19)

If someone desires other than the submission as a religion, it will not be accepted of him. (3:85)

In these two verses, both the word religion and al-islam (“the submission”) can be understood in broader or narrower senses. Most Muslims read them to mean that the right way of doing things is that set down by the Koran and the Hadith. Others understand the verses to mean that every revealed religion is one of the forms of islam, just as the message of all the prophets is tawhid. If someone rejects God’s religion—that is, “the submission” revealed to all the prophets—and follows instead a human concoction, God will not accept that from him. Having one’s religion rejected by God is the same as being sent to hell.

Some of the verses that speak of islam might well be read as referring exclusively to the religion brought by Muhammad (Pbuh), because he is mentioned in the context:

They count it as a favor to you that they have submitted. Say: “Do not count your islam as a favor to me. No, rather God confers a favor upon you, in that He has guided you to faith.” (49:17)

Today I have perfected your religion for you, and I have completed My blessing upon you, and I have approved islam for your religion. (5:3)

Several other Koranic verses that refer to islam or muslims can be read as referring to the historical religion of Islam. But at least one verse refers to islam in a still narrower sense. Apparently a group of bedouins—that is, tribes people who lived a nomadic existence in the desert—had seen that the new religion was the rising power in their region and that they could gain advantages by joining up with it. Hence they came before the Prophet (Pbuh) and swore allegiance to him in the time-honored manner of the Arabs. But of course, Islam came with a set of conditions that were completely unfamiliar to the bedouins; that is, the five practices of the religion that are mentioned in the hadith of Gabriel[2] and part of swearing allegiance to the Prophet (Pbuh) was agreeing to observe these practices. At some point, after having sworn allegiance, the bedouins told the Prophet that they had faith in Islam. Now God enters the discussion by revealing the following verses to Muhammad (Pbuh):

The bedouins say, “We have faith.” Say: “You do not have faith, rather say, ‘We have submitted,’ for faith has not yet entered your hearts. If you obey God and His messenger, He will not diminish you anything of your works.” (49:14)

In this verse, it is clear that submission is not the same as faith (iman), since submission means obeying God and the Prophet (Pbuh), whereas faith is something deeper, having to do—as we will see later—with knowledge and commitment. Obeying God and the Prophet (Pbuh) pertains to the domain of activity, to the realm of commands and prohibitions. The Prophet (Pbuh) has come with specific instructions from God for the people. If they obey the Prophet (Pbuh) they obey God’s instructions.

“Whosoever obeys the Messenger, thereby obeys God” (4:80).

God, in turn, will pay them their wages. It is this fourth meaning of the word that is the topic of the present chapter and is made most explicit in the hadith literature. Thus the hadith of Gabriel, in defining submission, simply lists a set of activities that must be performed in order for people to obey God:

Submission

is that you witness that there is no god but God and Muhammad is His messenger, that you perform the prayers, you pay the alms tax, you fast during Ramadan, and you make the pilgrimage to the House if you are able to go there.

In short, we have four basic meanings for the word islam, moving from the broadest to the narrowest:

(1) the submission of the whole of creation to its Creator;

(2) the submission of human beings to the guidance of God as revealed through the prophets;

(3) the submission of human beings to the guidance of God as revealed through the prophet Muhammad (Pbuh) ; and

(4) the submission of the followers of Muhammad (Pbuh) to God’s practical instructions. Only the third of these can properly be translated as Islam with an uppercase ‘I’. The other three will be referred to as “submission” or islam.

It should not be imagined that these four meanings are clearly distinct in the minds of Muslims, especially those who live in the ambiance of their religion. It is common for Muslims to think of Islam as their own practices, and to think of their practices as the same as the practices of all religions (since all religions are islam). If other practices are different, it must be because they have become corrupted. In the same way it is common for traditional Muslims to think that their own religious activities are the most normal and natural activities in the universe, since they are simply doing what everything in creation does constantly, given that “to Him has submitted whoso is in the heavens and the earth.” In other words, the various meanings of the terms become conflated and it is not always easy to separate them.[3]

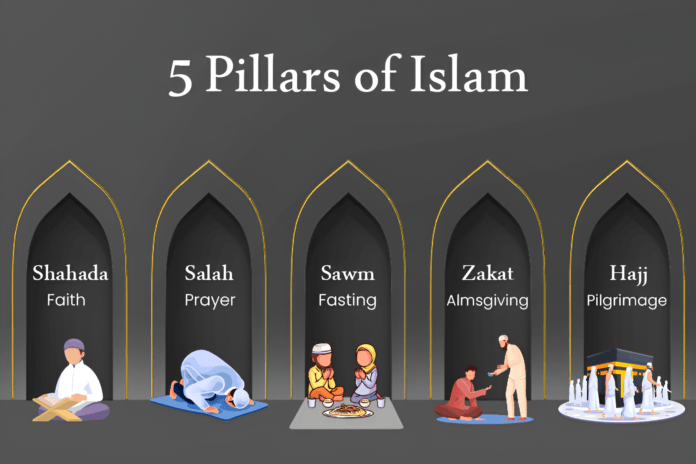

The Five Pillars

A pillar is a support, something that holds up a structure. The structure is the religion of Islam with its three dimensions. If the five fundamental practices of Islam are called “pillars,” the implication is that everything else depends upon them.

Practice: Embodied Submission

Practices pertain to the domain of the body. Our bodies determine our configuration within reality, so much so that there have always been people who claim that bodies make up the whole of existence, or at least everything significant. The Koran sometimes cites the criticisms that such people make of those who follow the prophets:

If you obey a mortal like yourselves, then you will be losers. What does he promise you that when you are dead, and become dust and bones, you shall be brought forth? Away, away with what you are promised! There is nothing but our life in this world. We die, and we live, and we will not be raised up. (23:34-37)

If bodies were not of such profound importance for human existence, people would not think in such terms. But bodies play a determining role in all the individual characteristics that give us our identity. Our meeting with our surroundings always begins on the bodily level, through the intermediary of the senses. If philosophers and theologians can speak of non bodily-realities, their words may have no meaning for children or unreflective people.

From the beginning Islam set out to build a society. What Islam has always understood is that people are united by common practices at least as much as by common ideals. Islam has functioned socially by harmonizing people’s activities.

The body is a lived reality for everyone, but non-bodily realities do not make much sense to many people. “Show me,” they say. And the Koran simply replies that salvation will be achieved by those who “have faith in the unseen.” At this first level, people are not asked to understand the unseen, simply to accept that it is there and to act accordingly, by performing the Five Pillars and the other activities set down in the revealed guidance.

For the most part, people are born into the religion they profess. Islam recognizes that correct practice makes people Muslims and that, for most people, correct belief follows upon correct practice. Muslim children are rarely taught a catechism. Rather they are taught to pray and to perform other rituals. They grow up performing basic purification rites, because these determine the nature of toilet training. And like children everywhere, they enjoy doing what grown-ups do, so they frequently follow along in the movements of the ritual prayer when their parents or other family members perform it. No one cares if they lose interest in the middle and go off to play. The point is for the practices gradually to become a natural and organic part of the human configuration.

Behind all the stress on practice is the recognition that the Koran must become flesh and blood. It is not enough for people to read the Koran or learn what it says. They have to embody the Book. It must become the determining reality of what they do (islam), what they think (iman), and what they intend (ihsan).

The First Pillar: The Shahadah

The pillars are practices, which is to say that they are described and defined in terms of activity. What do you do to be a Muslim? This question does not pertain to the level of faith, understanding, or intention. Questions on that level belong to Islam’s second or third dimensions, not the first.

The first pillar is the fundamental act upon which all Islamic activity depends. It is to acknowledge verbally that one accepts the reality of God and the prophecy of Muhammad (Pbuh) (and hence the truth of the Koran, the message with which Muhammad was sent). It is known as the Shahadah (Arabic shahada, which means “to testify” or “to bear witness”).

The Koranic usage of the term shahada throws interesting light on its significance. One of God’s Koranic names is “Knower of the ghayb and the shahada.” Ghayb means “the absent, the unseen, the invisible, the hidden.” Shahada means “that which is visible or witnessed.” By employing this divine name and in other ways as well, the Koran divides reality into two realms, that which is absent from our senses, and that which our senses are able to witness. We know only the witnessed realm, while God knows both the witnessed and the invisible realms. Included in the unseen realm are God and spiritual beings while included in the witnessed domain are all bodily things. Another of God’s names is al-shahid, the ‘Witness’, for God is witness to everything that happens, because, as the Koran puts it:

He is with you wherever you are. (57:4).

God is Witness of what they do. (6:19)

Suffices it not as to thy Lord, that He is Witness over everything? (41:22)

The Koran also frequently uses the term shahada in the sense of giving witness. For example, it tells people that when someone borrows money, two witnesses should be present and the whole transaction should be recorded;

“That is more equitable in God’s sight, and more reliable as shahada” (2:282).

The act of bearing witness to God’s unity is the most basic act of Muslims. By performing it, they imitate God and the angels, who also perform it, and they enter into the ranks of those who have been given knowledge:

God bears witness that there is no god but He—and the angels, and the possessors of knowledge—upholding justice; there is no god but He, the Inaccessible, the Wise.(3:18)

In its briefest form, Islam’s first pillar is simply to say the two sentences, “There is no god but God” (la ilaha illa’llah) and “Muhammad is God’s messenger” (Muhammadun Rasul Allah).

Normally, the words “I bear witness that” (ashhadu an) are added before each sentence.

Theoretically, it is only necessary for a Muslim to utter the Shahadah once in his or her lifetime, but in practice, Muslims recite it frequently, especially because it is incorporated into the daily required prayers. Traditionally, a child’s father whispers the Shahadah into its ear at birth, thus the child is exposed to the first pillar at the very beginning of life. The formula is recited by Muslims on all sorts of occasions, and a child is taught to say it as early as possible.

No one supposes that the child understands the Shahadah. It is the act itself that is important. The Shahadah’s primary importance comes out clearly in the fact that reciting the Shahadah is the ritual whereby one submits oneself to God, that is, becomes a Muslim. In this ritual, the formula must be recited in Arabic, with the intention of submitting oneself to God, in the presence of two Muslim witnesses.

Most Muslims agree that pronouncing the Shahadah is all that is absolutely necessary for one’s Islam to be accepted by God. However, they add that Islam is not genuine and sincere if it remains simply verbal. By reciting the Shahadah, one makes the remaining four pillars incumbent upon oneself, and if one does not observe them, one’s Islam is lacking, if not unacceptable.

The Second Pillar: Salat

Although uttering the Shahadah is the fundamental act of Muslims, performing the salat (ritual prayer) is, in a certain sense, even more basic. The Prophet called salat the “centerpole” of the religion, suggesting the image of a tent with a single pole holding it up in the middle and with other poles as secondary supports. The Koran commands performance of the salat more than it commands any other activity[4], and prophetic sayings suggest that God loves the salat more than every other human act. It is not accidental that performing the ritual prayer in communion has come to symbolize Islam on television. For TV producers, the reason is simply that the salat makes good footage but for Muslims, this act embodies what it means to be a Muslim more than any other, and Muslims have always recognized that this is the case.

Like many other Koranic terms, the word salat has several meanings. The basic sense of the word in Arabic is to pray or bless. Just as God and the angels utter the Shahadah, so also they perform the salat. And just as people bear witness to God’s oneness in imitation of God, so also they perform the prayer in imitation of God. In Koranic usage, there are at least four forms of salat:

First, God and the angels perform a salat whereby they bless God’s servants.

It is He who performs the salat over you, and His angels, that He may bring you forth from the darkness into the light. (33:43).

Second, all creatures in the heavens and the earth perform salat as the expression of universal islam.

Have you not seen that everyone in the heavens and the earth glorifies God, and the birds spreading their wings? Each one knows its salat and its glorification. (24:41).

Third, every voluntary muslim performs the salat, which is to say that the term is applied to one of the specific forms of worship revealed to all the prophets.

And We delivered [Abraham], and Lot. . . . And We gave him Isaac and Jacob as well, and every one We made wholesome. . . . And We revealed to them the doing of good deeds and the performance of the salat. (21:73)

Fourth, Finally, in the most common usage of the term, salat refers to the specific form of ritual that is the second pillar of Islam.

Although the Koran repeatedly commands Muslims to perform the salat, it says little about what the salat actually involves. How to perform the salat was taught by the Prophet (Pbuh), and thus Muslims today, wherever they live, pray in essentially the same way that Muhammad (Pbuh) prayed and taught them to pray. [Note: Minor variations among different fiqh are insignificant].

Salat is divided into two basic kinds—required and recommended. The required salat is the second pillar, while other salats are recommended on all sorts of occasions. The primary required salat is performed five times a day, while there are other occasional forms, such as the congregational prayer on Fridays. After sunset (the beginning of the day in Islamic—as in Jewish—time reckoning) and before the disappearance of the last light from the horizon, the first of the five daily prayers, the evening salat, is said. The next prayer is the night salat, whose period extends from the end of the time of the evening prayer to the beginning of the time of the morning prayer. The morning salat can be said any time between the first appearance of the dawn and sunrise.[5] The fourth salat is said between noon and mid afternoon. Noon is the time when the sun reaches the meridian—not clock noon, which seldom coincides exactly with solar noon. Midafternoon is usually defined as the time when something’s shadow is slightly longer than the thing itself. The period for saying the fifth salat extends from midafternoon until sunset.

Each prayer consists of a certain number of cycles (rak`a). The evening salat has three cycles, the night four, the morning two, the noon four, and the afternoon four. Each cycle involves a number of specific movements and the recitation of a certain amount of Koranic text and various traditional formulas, all in Arabic.

If we were to observe a group of people performing the salat together, we would see the following (perhaps with slight differences from place to place): First, those performing the salat stand up straight. After a minute or two, they bow at the waist with backs straight. After a few seconds, they stand up straight again, then almost immediately they place their knees, hands, and foreheads on the ground. They remain in this position of prostration for a few seconds, then come up for a second or two to a sitting position, then prostrate themselves for a second time.

This is the end of the first cycle. From the position of prostration, they go back to a standing position and begin a second cycle, exactly like the first. After the second cycle, instead of standing again, they come up to a seated position and recite formulae of blessing and peace directed to the Prophet (Pbuh) and the faithful.

Here they also recite the Shahadah in an elongated form. If this prayer that we have just observed is the morning salat it now comes to an end with greetings of peace to the right and the left. If it is any of the other prayers, it goes into a third cycle. The evening prayer ends after the third cycle, with the seated Shahadah, blessings, and greetings. The other three salats have four cycles, so they correspond to the morning prayer performed twice.

During the two, three, or four standing parts of the prayer, Muslims recite the Fatihah, which is the first chapter of the Koran, consisting of seven short verses. In the first two cycles, they also recite another chapter or some verses from the Koran.

In order to perform the salat, people must be in a state of ritual purity (tahara). For practicing Muslims, maintaining ritual purity is a daily concern, since it involves preserving the body and clothing from contamination by excretions and blood. Muslim toilet training is determined by the rules of ritual purity. Although children are not expected to perform the prayers until puberty, even infants are taught to clean themselves in a way that keeps them ritually pure. What this cleaning involves is basically careful elimination of all traces of bodily wastes, preferably with water.

There are two main categories of impurity, and two basic kinds of ablution to remove impurity. The major ablution (ghusl) is required after sexual intercourse or emission of semen, menstruation, childbirth, and touching a human corpse. A person without a major ablution cannot perform the ritual prayer and should not enter a mosque or touch the Koran. In order to perform the salat, one has to be free from minor impurity as well. This kind of impurity occurs if one sleeps, goes to the toilet, breaks wind, and in certain other ways as well. It is removed by a minor ablution (wudu’).

The major ablution involves washing the whole body from head to toe, making sure that every part of it gets wet. The minor ablution involves rinsing or wiping the following with water, in this order: the hands, the mouth, the nose, the right and left forearms, the face, the head, the ears, and the right and left feet.

If there is no access to water, or if a person should not touch water because of illness or some other reason, and if the time for prayer arrives, a simpler form of ablution is made with clean sand or a stone. Called a tayammum, it can replace both major and minor ablutions.

The five daily prayers are incumbent on all Muslims who have reached puberty. However, women who are impure because they are menstruating or have just given birth should not perform the salat. People who are too ill to pray are excused; if they are well enough to recite the prayers seated or lying down, they should do that[6]. Just as people must have been purified through the ablutions before they can perform the salat, so also their clothing and the place where they perform the salat must be pure. Clothing is pure as long as it has not been tainted by human or animal excrement, urine, semen, or blood. Following the Sunnah of the Prophet (Pbuh), Muslim men traditionally squat when they urinate, in order to avoid splashing their clothing with urine. If clothing becomes impure, it must be rinsed before it can be worn while one performs the salat.

In the same way, the place of prayer must be kept pure. Practicing Muslims normally keep their homes pure, which explains why they (like Far Easterners) remove their shoes before entering the house. They will commonly pray in their homes wherever purity is preserved. In places inside or outside the house that are impure or of questionable purity, people put down a piece of cloth or a prayer carpet, which they then fold up and put away when they finish. This cloth or carpet is called a sajjada, a “place of much prostration.”

Nature is by definition pure, and it is common in Muslim countries to see people praying in the fields by the side of the road. The main way to purify clothing or carpeting that has become impure is to wash it, but if the impure substance itself has been removed, placing the article in the sun for two or three days will also purify it. Saying prayers in congregation is highly recommended. According to the Prophet, a salat said in congregation is rewarded with seventy times the reward of a salat said alone. A congregation is defined as two or more people praying together. Hence a husband and wife or a mother and her child are a congregation when they pray together. But in general, it is felt that the larger the congregation, the better, and this fits in nicely with the social dimension of much of Islamic practice.

The places in a community where congregational prayers are held are called “mosques.” This English word is derived from the Arabic masjid, which means “place of prostration.” The social house of worship is called a masjid because prostration is understood as the salat’s highpoint, as it were. It symbolizes the utter submission and surrender (islam) of the human being to God. Men must attend the mosque once a week for the Friday congregational prayer, which is held in place of the noon prayer. Women are not required to go. Shi’ite Muslims maintain that the Friday prayer, although recommended, is not incumbent.

The rhythm of life in a traditional Islamic society is largely determined by the five daily prayers. Even today, one is made aware of this rhythm in any Muslim city by the call to prayer—the adhan—that is made at every mosque to summon the faithful to salat. Except for the first sentence, which is recited four times, and the last, which is recited once, each sentence is recited twice.

God is greater.

I bear witness that there is no god but God.

I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God.

Hurry to the salat.

Hurry to salvation.

God is greater.

There is no god but God.

In the morning adhan, the sentence “The salat is better than sleep” is usually added after “Hurry to salvation.”

The person who recites the adhan, the muezzin, is typically selected for his strong and beautiful voice. In a traditional city, where there are many mosques located not far from each other, one hears a symphony of beautiful voices, each reciting the adhan in a slightly different rhythm and tune. This is particularly striking and moving at the time of the morning adhan, when the city is otherwise silent. Nowadays, most people in charge of mosques have lost their sense of beauty and harmony. Instead of hearing a variety of beautiful voices issuing from the minarets, people hear the sound of loudspeakers. Often every mosque broadcasts the recorded voice of the same muezzin[7]. Although the voice may be beautiful, loudspeakers make even the most beautiful recording ugly. The adhan becomes an electronic imposition that can be quite disturbing, not only to travelers, but also to the locals who have preserved their taste.

A great deal can be said about the significance of the salat for Muslim life. Here we will only remark that observing it has a deep effect on both the individual and collective psyches. The whole color of a society in which most people perform five daily prayers is profoundly different from one in which there is no time for God, or in which religion is a private affair, or reserved only for one day a week. The following hadith puts the prayer’s effect into a nutshell:

God’s messenger said, “Tell me, if one of you had a river at his door in which he washed five times a day, would any of his filthiness remain?”

The people replied, “Nothing of his filthiness would remain.”

He said, “That is a likeness for the five salats. God obliterates sins with them.”

The Third Pillar: Zakat

Zakat is commonly translated as “alms tax.” It is defined as a certain percentage of one’s acquired property or profit for the year that is paid to the needy. In keeping with the Koran (9:60)[8], there are eight categories of people to whom zakat should be given: the needy, the poor, those who collect the zakat, those whose hearts are to be reconciled to Islam, captives, those in debt, those who are fighting in God’s path, and travelers. The rules and regulations for calculating zakat are quite complex. Depending on the nature of the property and the conditions under which it was acquired, it can range from 2.5 percent to 10 percent of one’s profit.

The root meaning of the word zakat is “purity.” The basic idea behind zakat is that people purify their wealth by giving a share of it to God. Just as ablutions purify the body and salat purifies the soul, so zakat purifies possessions and makes them pleasing to God. Zakat has an obvious social relevance. Purification of an individual’s possessions takes place through helping others. In order to pay it, one has to concern oneself with the situation of one’s neighbors and discover who the needy are. Salat, like zakat, has a social significance, but what is required is that the salat be recited, not that it be recited with others. In contrast, zakat depends totally upon social interaction. One cannot pay zakat to oneself.

Paying zakat depends not only on the circumstances of those who receive, but also on the circumstances of those who pay. In other words, people pay zakat only if they fulfill the required conditions. They must have had an income over the year and made a profit[9]. Those who do not fulfill these conditions cannot pay zakat. If they give charity in spite of their own need, this is praiseworthy, but it is not the required zakat because it does not fulfill the conditions. [Note: This is general view of the author, follow your respective fiqh]

This way of looking at zakat is a typical example of how Islam sets up priorities. Certain things are absolutely obligatory, like the Shahadah and the ritual prayer. Others depend upon circumstances, like the zakat. Notice that what is absolutely essential pertains to the individual, because there is always a person who stands before God. What is secondary pertains to society, because one is not necessarily a part of any given social conditions. This means, in brief, that Islam asks Muslims to put their own houses in order first. Only then are they expected to look at other people’s houses, according to the instructions given by God. In short, the primary task is to set up a right relationship with God, and this begins with the individual. A healthy society can only exist when its members are healthy. The individuals who make up the society are the primary focus of attention. But their religious well-being demands that they accept some measure of social responsibility. If, as the Prophet (Pbuh) said, “Marriage is one-half of the religion,” this is because the family is the fundamental building block of society. If the family can be kept healthy—and this depends on the spiritual health of its members—then society can be kept healthy.

The Fourth Pillar: Fasting

The fourth pillar is “to fast during the month of Ramadan.” Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar. Since this is a lunar calendar of 355 days, each month lasts twenty-nine or thirty days. For a month to be considered as having twenty-nine and not thirty days, the new crescent moon must have been sighted. This helps explain why day begins at sundown: the new moon is seen at sunset on the western horizon, and then it sets. If it is cloudy and people have to depend upon calculation to decide if the new month has begun or not, the month is counted as lasting thirty days.

The month of Ramadan begins when the new crescent moon is sighted, or when the previous month reaches thirty days. Fasting begins at dawn the next morning. Dawn is defined as the time when the earliest light shows on the eastern horizon, or the time when one can see the difference between a black and a white piece of string by natural light. This is the time of the morning adhan, about an hour and a half before sunrise. The fast comes to an end when the sun sets; that is, when the evening adhan is sounded.

Fasting consists of refraining from eating, drinking, smoking, and sexual activity. All Muslims who have reached the age of puberty are required to fast, although there are several valid excuses for not fasting, such as illness and travel, and, while pregnant or menstruating, women are forbidden from fasting. Missed fasting needs to be made up for at another time, at the discretion of the person. Ramadan is a time of heightened attention to the rules of right conduct. For example, the Prophet said, “Five things break the fast of the faster—lying, backbiting, slander, ungodly oaths, and looking with passion.” In other words, at a time when certain normally permitted acts are forbidden, acts that are always forbidden ruin a person’s fast.

The fact that Ramadan is a lunar month has interesting consequences. Except for the spring and autumn equinoxes, every daytime period of the year is of a different length in different locations on the face of the earth. The daylight hours in June are long in the northern hemisphere and short in the southern hemisphere. A solar month when every Muslim in the world would fast the same amount of time cannot be found—especially when one remembers that the pre-Islamic Arab solar calendar was observed by adding an extra month every three years to the lunar calendar, similar to what is done with the Jewish calendar. But the use of the lunar calendar demands that all Muslims who fast for a period of thirty-three years will have fasted for the same amount of time, no matter where they live.

Because of the lunar calendar, Ramadan moves forward in the solar calendar about eleven days every year. Thus in the year 1998 C.E., the first day of Ramadan corresponds to December 20 (give or take a day); in 1999 to December 9; in 2000 to November 28; and so on. People living in northern latitudes who will be fasting for only eight or nine hours a day during December will be fasting for seventeen or eighteen hours a day after seventeen years when Ramadan comes in June. Thus most people’s lives follow a cycle regulated by Ramadan, where fasting becomes easier and then more difficult. Like the other pillars, fasting has a strong social component. When the pattern of individual life changes, the effects are multiplied in society. In a traditional Islamic community, all places of eating are closed during the daylight hours of Ramadan. People usually have a good-sized meal just before the beginning of the fast in the early morning. Depending on the time of the year and their own habits, they may then stay awake or go back to sleep after saying their morning salat. For the rest of the day, they go about their activities more or less as usual.

Those who have not experienced the fast of Ramadan may think it is easy to skip breakfast and lunch, but what about that morning cup of coffee? Even a sip of water makes a difference after a heavy sleep, since it helps turn the metabolism around. In winter it is not difficult to go eight hours without food or drink, but what about June or July? One day may be easy, but what about one week, two weeks . . . ? Unless people are firm in their faith, they are not likely to make it through the whole month, summer or winter. But to suggest that fasting during Ramadan is difficult does not mean that Muslims find it to be a hardship. By and large Ramadan tends to be the happiest time of the year, although this does not become obvious until the night. During the daytime, people are too subdued to show their happiness. Traditional Islamic cities are sights to behold during the month of fasting. Daylight hours and nighttime exhibit a total contrast. During the day there is relatively little activity, many shops are closed, and people tend to be quiet, if not morose. But as soon as the cannon sounds or the adhan is proclaimed, the whole atmosphere changes. Everyone has been anxiously waiting for the day’s fast to end. If they follow the example of the Prophet (Pbuh), they immediately eat a date or two or have a drink of water, then say their evening salat. In public areas, right before sundown, the tea houses and restaurants are full of people sitting patiently, food and drink before them.

In many parts of the Islamic world it has become the custom to have a feast as soon as the fasting ends. In any case, the nights of Ramadan are festive occasions. The city streets come alive with the activity that is reserved for daylight hours at other times of the year. According to Islamic law, not observing the fast is a serious sin. In order to make up for a single day missed intentionally, a person must fast for two months. However, as is often the case, there is no way to enforce this rule. People have only themselves and God to answer to. In traditional Islamic society, everyone carefully observed the fast in public. In private, they could do whatever they wanted, and no one but God was the wiser.

Today, in some of the larger cities in the Islamic world, one may have the impression that few people fast. Restaurants are busy and life seems to be going on as usual. But even in the West, many Muslims who do not observe the pillars of Islam fast for at least a day or two. (In a similar way, residual Christians are likely to go to church once a year at Easter). Part of the reason for token shows of fasting is that the fast is the one ritual that is strictly between the individual and God. Though it has social dimensions, God alone sees whether or not a person observes it. Hence Ramadan is usually considered to be the most personal and spiritual of the pillars. It is a test of people’s sincerity in their religion. The salat can be seen by other people, and in a tight-knit society, everyone knows how well others observe it. But no one can check on your every movement during the day to see whether or not you have taken a sip of water or nibbled a snack. Many otherwise lapsed Muslims sense this, and so they fast for a day or two just to let themselves and God know that they have not left the fold.

The Fifth Pillar: Hajj

The fifth pillar is to “make the pilgrimage to the House of God if you are able.” The hajj is a set of rituals that take place in and around Mecca every year, beginning on the eighth and ending on the thirteenth day of the last lunar month, Dhu’l-Hijja (The Month of the Hajj). Mecca was a sacred center long before Islam, and according to Muslim belief, Adam himself built a sanctuary at Mecca. Eventually it was rebuilt by Abraham, and by the time of the appearance of Islam, the Kaaba (Cube) had long been a place of pilgrimage for the Arab tribes. The Koran and the Prophet (Pbuh) modified and re-sanctified the rituals performed at the Kaaba, making them a pillar of the religion.

Muslims are required to make the hajj once in their lifetimes, but only if they have the means to do so. To understand some of the significance of the hajj, one needs to remember that steamships, airplanes, and buses are products of the past one hundred years. For thirteen hundred years, the vast majority of Muslims made the journey to Mecca on foot, or perhaps mounted on a horse or a camel. It was not a matter of taking a two-week vacation, and then back to the office on Monday morning. Rather, for most Muslims the hajj was a difficult journey of several months if not a year or two. And once the trip was made, who wanted to hurry? People stayed in Mecca or Medina for a few months to recuperate and to prepare for their return, to meet other Muslims from all over the Islamic world, and to study. Often they stayed on for years, and often they simply came there to die, however long that might take.

Today, one can go to Mecca in a few hours from anyplace in the world. Some people decide to do the hajj this year because they did Bermuda last year. In the past, most Muslims had to fulfill strict conditions in order to make the journey. In effect, they had to be prepared for death. They had to assume that they would never return, and make all the necessary preparations for that eventuality. One of the conditions for making the hajj is that people have to pay off all their debts. If a man wanted to make the hajj, but his wife did not want to accompany him, he had to make sure that she was provided for in the way in which she was accustomed. He had to see to the provision of his children as well, and anyone else for whom he was responsible. Traditionally, the hajj was looked upon as a grand rite of passage, a move from involvement with this world to occupation with God. In order to make the hajj, people had to finish with everything that kept them occupied on a day-to-day basis. They had to answer God’s call to come and visit him. The hajj was always looked upon as a kind of death, because the Koran repeatedly describes death as the meeting with God, and the Kaaba is the house of God.

The hajj, in short, was a death and a meeting with God, and the return from the hajj was a rebirth. This helps explain why the title “hajji” (“one who has made the hajj”) has always been highly respected throughout the Islamic world. Hajjis were looked upon as people who were no longer involved with the pettiness of everyday life. They were treated as models of piety and sanctity, and no doubt most of them assumed the responsibilities toward society that the title implies, even if some took advantage of the respect that was accorded to them.

A Sixth Pillar? Jihad and Mujahada

Some authorities have held that there is a sixth pillar of Islam: jihad. This word has become well-known in English because of the contemporary political situation and the focus of the media on violence. Hence, a bit more attention has to be paid to it than would be warranted if we were simply looking at the role that jihad plays in Islam. The first thing one needs to understand about the term jihad is that “holy war” is a highly misleading and usually inaccurate translation. In Islamic history, the label has been applied to any war by “our side.” Until very recently in the West, the situation was similar; every war was considered holy, because God was on our side. By employing the term, Muslims condemned the other side as anti-God. In short, the word has played the role of patriotic slogans everywhere. To undertake a jihad is, in contemporary terms, “to fight for the preservation of democracy and freedom.” It is to do what the good people do.

The Koranic usage of the term jihad is far broader than the political use of the term might imply. The basic meaning of the term is “struggle.” Most commonly, the Koran uses the verb along with the expression “in the path of God.” The “path of God” is of course the path for right conduct that God has set down in the Koran and the example of the Prophet.

From one point of view, jihad is simply the complement to islam. The word islam, after all, means “submission” or “surrender.” Westerners tend to think of this as a kind of passivity.

But surrender takes place to God’s will, and it is God’s will that people struggle in His path. Hence submission demands struggle. Receptivity toward God’s command requires people to be active toward all the negative tendencies in society and themselves that pull them away from God. In this perspective, submission to God and struggle in his path go together harmoniously, and neither is complete without the other.

Within the Islamic context, the fact that submission to God demands struggle in his path is self-evident. Salat, zakat, fasting, and hajj are all struggles. If you think they are easy, try performing the salat according to the rules for a few days. In fact, the biggest obstacles people face in submitting themselves to God are their own laziness and lack of imagination. People let the currents of contemporary opinion and events carry them along without resisting. It takes an enormous struggle to submit to an authority that breaks not only with one’s own likes and dislikes, but also with the pressure of society to conform to the crowd.

The place of jihad in the divine plan is typically illustrated by citing words that the Prophet (Pbuh) uttered on one occasion when he had returned to Medina from a battle with the enemies of the new religion. He said, “We have returned from the lesser jihad to the greater jihad.” The people said, “O Messenger of God, what jihad could be greater than struggling against the unbelievers with the sword?” He replied, “Struggling against the enemy in your own breast.” In later texts, this inward struggle is most often called mujahada rather than jihad. Grammatically, the word mujahada—which is derived from the same root as jihad—means exactly the same thing. But the word jihad came to be employed to refer to outward wars as well as the inward struggle against one’s own negative tendencies, while the word mujahada is used almost exclusively for the greater, inward jihad.

Those Muslim scholars who have said that jihad is a sixth pillar of Islam have usually had in mind the fact that struggle in the path of God is a necessity for all Muslims. At the same time, they recognize that this struggle will sometimes take the outward form of war against the enemies of Islam. But it needs to be stressed that in the common language of Islamic countries, the word jihad is used for any war. In a similar way, most Americans have considered any war engaged in by the United States as a just war. But from the point of view of the strict application of Islamic teachings, most so-called jihads have not deserved the name. Any king (or dictator, as we have witnessed more recently) can declare a jihad. There were always a few of the religious authorities who would lend support to the king—such as the scholar whom the king had appointed to be chief preacher at the royal mosque. But there have usually been a good body of the ulama who have not supported wars simply because kings declared them. Rather, they would only support those that followed the strict application of Islamic teachings. By these standards, it is probably safe to say that there have been few if any valid jihads in the past century, and perhaps not for the past several hundred years.

To be continued ……

https://SalaamOne.com/vision

https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX-kZcyXzjWeGbe6j/pub

[1] The triliteral root sīn lām mīm (س ل م) occurs 140 times in the Quran, in 16 derived forms: https://corpus.quran.com/qurandictionary.jsp?q=slm

[2] https://wp.me/scyQCZ-jibriel, https://bit.ly/Hadith-Jibriel. حدیث ِجبرائیل اُمّ السنۃ: https://bit.ly/Hadis-Jibril

Umar ibn al-Khattab said: One day when we were with God’s messenger, a man with very white clothing and very black hair came up to us. No mark of travel was visible on him, and none of us recognized him. Sitting down before the Prophet, leaning his knees against his, and placing his hands on his thighs, he said, “Tell me, Muhammad, about submission.” He replied, “Submission means that you should bear witness that there is no god but God and that Muhammad is God’s messenger, that you should perform the ritual prayer, pay the alms tax, fast during Ramadan, and make the pilgrimage to the House if you are able to go there.” The man said, “You have spoken the truth.” We were surprised at his questioning him and then declaring that he had spoken the truth. He said, “Now tell me about faith.” He replied, “Faith means that you have faith in God, His angels, His books, His messengers, and the Last Day, and that you have faith in the measuring out, both its good and its evil.” Remarking that he had spoken the truth, he then said, “Now tell me about doing what is beautiful.” He replied, “Doing what is beautiful means that you should worship God as if you see Him, for even if you do not see Him, He sees you.” Then the man said, “Tell me about the Hour.” The Prophet replied, “About that he who is questioned knows no more than the questioner.” The man said, “Then tell me about its marks.” He said, “The slave girl will give birth to her mistress, and you will see the barefoot, the naked, the destitute, and the shepherds vying with each other in building.” Then the man went away. After I had waited for a long time, the Prophet said to me, “Do you know who the questionnaire was,Umar?” I replied, “God and His messenger know best.” He said, “He was Jibriel . He came to teach you your religion.” [http://www.equranlibrary.com/hadith/muslim/1366/93]

[3] A sympathetic observer of Islam, John Esposito, writes, “Islam is not a new religion with a new Scripture. Instead of being the youngest of the major monotheistic world religions, from a Muslim viewpoint it is the oldest religion” (Islam: The Straight Path [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988], p. 22). Many Muslims do indeed believe this, but they do so by conflating the meanings of the term islam as found in the Koran.

[4] https://tanzil.net/#search/quran/صَلَا, https://corpus.quran.com/qurandictionary.jsp?q=Slw

[5] The traditional method of determining the time of dawn mentioned in the Koran involves trying to see the difference (on a moonless night) between a black string and a white string. This works out to roughly one or one and one-half hours before sunrise, varying according to latitude. In Islamic countries, most people live within earshot of a mosque and therefore hear the morning call to prayer at this time.

[6] https://islamqa.info/en/answers/105356/how-should-the-sick-person-purify-himself-and-pray

[7] Not necessarily prerecorded.

[8] https://www.islamawakened.com/quran/9/60/default.htm, https://corpus.quran.com/translation.jsp?chapter=9&verse=60

[9] Paying Zakat is mandatory for all Muslims who have surplus wealth, which they aren’t using for their own basic needs. These surplus savings you have must be above a set minimum amount, called ‘Nisab.’ If it is, and if you’ve held them for a year, then you should be paying Zakat. Zakat is 2.5% of your savings, which the poor and needy have a right over https://akhuwatuk.org/zakat/