The recent standoff between India and Pakistan has become a familiar script where every few years both countries reach this crossroad and after a few days of saber rattling and flurry of international diplomatic activity they pull back. The conflict began on April 23, 2025, following a terrorist attack in the Pahalgam valley of Indian controlled Jammu and Kashmir, which resulted in the death of twenty-seven tourists.

India claimed that Pakistan was behind this attack without sharing any evidence. Pakistan, on the other hand, denied any involvement.

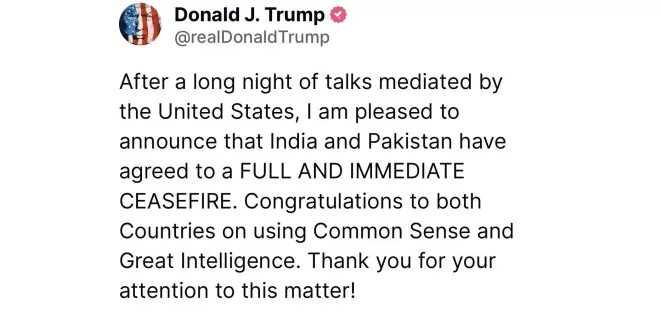

There were missile and drone attacks by both sides and seventy-two hours later President Donald Trump announced on twitter that both sides have agreed to a ceasefire. Whenever such a standoff occurs, hyperactive Indian and Pakistani media and few news items in international media run usual narrative and a familiar cast of regional experts weigh in before everything fizzles out and the whole show is usually over in a few days.

This article will look at the deeper aspect of the thought process of both sides rather than the periodic symptoms that appear every few years.

It is an exercise of analyzing the behavioral psychology of both sides. In a crisis, current intelligence, which according to Robert Clarke covers fast breaking events is like ‘newspaper or television news reporting’ but this article will look at the issue in depth and trajectory over long term that is more like ‘world of university or a research laboratory’.

Individual and organizational processing of information is influenced by previous experience and organizational norms. This background exerts influence on what is observed, which information is considered relevant and how this information is processed, organized, and interpreted. This is the mindset that operates during a crisis and controls the perception.

In the case of India, civilian decision makers are in control of national security decisions and the military and intelligence agencies are under civilian control. In Pakistan, the army performs both roles and is the final arbiter of all major decisions. Indian and Pakistani security personnel and decision makers have a mental image of the other and all information filters through this existing image.

Psychological experiments have shown that once a mental image is formed it is very resistant to change despite the availability of new and more accurate information. Both sides have a set of assumptions and expectations about the motivation of the other side and perceive what they expect to perceive.

Information that meets expectations is quickly recognized and assimilated while contrary information is ignored, explained away or considered an anomaly. If a security analyst or decision maker has already reached a conclusion without reliable evidence, any incoming information can fit into the existing belief especially if contradictory information is rejected.

This sets the stage for ‘perceptual bias’ that is aggravated by organizational or political need for consistency. Revision is perceived negatively as it implies that the earlier judgement was incorrect. This was operative on the Indian side in the immediate aftermath of the attack on tourists.

The right approach is to encourage revision that simply suggests that earlier judgment was based on information available at that time and now that additional and more accurate information is available that requires revision.

Both India and Pakistan fall victim to ‘centralization misperception’ where adversary’s all moves are viewed as carefully planned and coordinated and actions emanating from a centralizing process. This view is held despite their own experience with short term political compulsions of decision makers rather than strategic thought, mediocre military and foreign policy bureaucracy, ignorance, errors, and chance occur rences. It is entirely possible that an event occurred with no link with the usual suspects but accepting this phenomenon is what Robert Jervis calls ‘psychologically uncomfortable and intellectually unsatisfying’.

The Indian narrative is that the attack on tourists was either planned or given approval by the Pakistani state, specifically the army. Pakistan’s narrative is that it was a ‘false flag’ operation conducted by the Indian security establishment for specific gains. Both sides have fallen victim to the ‘single hypothesis’ trap that suits the existing national narrative.

Any information that aligns with the mindset is quickly assimilated in the existing model while information that is contradictory is explained away, ignored or considered as an anomaly. A correct approach is having several alternative hypotheses and information should be judged on its merit and see which hypothesis it rejects rather than which information supports existing assumption. Rigorous exercise to reject a hypothesis should be the criterion rather than finding only supporting evidence. It is possible that both Indian and Pakistani conclusions are wrong and a militant group after careful evaluation of the events of the last few years concluded that their cause was eclipsing and something needed to be done to challenge the status quo. They decided to act now but did not have the capacity for a high profile, complex and expensive operation therefore a decision was made for a low cost, simple attack on a soft target. Three or four militants with AK-47 rifles and few magazines walking in a valley away from heavily patrolled large population centers, killing two dozen tourists in few minutes and disappearing in the forest. The ensuing response of both countries was beyond their expectations as suddenly two nuclear armed countries were facing each other down with international headlines about Kashmir.

A careful study of conflicts of the last two decades shows that militant networks capitalize on the conflict between nation states. Escaping the ‘cages of mind’ is a challenging task and usually professional analytic segments of military, intelligence and foreign policy establishments, academia, think tanks and investigative journalist community are engaged in such exercise but unfortunately all these avenues are either absent or very weak in India and Pakistan.

India and Pakistan are chained by what is called ‘affirming conclusions’. Information that affirms existing assumptions is quickly assimilated without question while information that challenges existing belief is discarded. The most challenging but most rewarding task is to take all existing data out of mind and make it explicit, preferably in written form, reorganize it and look at it from different perspectives.

This requires first acknowledging biases and then taking this fact into assessment process. Expose familiar information to challenges to see if it passes the test of scrutiny. Opening the windows always refreshes the environment. Unfortunately, very few analysts, let alone decision makers take this road. During crisis, the need for current intelligence sucks all the oxygen from the system as policy makers are pushing the collectors and analysts for interpretive analysis of large amount of incoming data that requires ‘early judgment’ on incomplete, ambiguous, and sometimes contradictory information. The art is to pick the relevant information that is a challenging task in short term analysis as there is fear that something is missing that can have a negative impact on ongoing crisis. It is easier for medium- and long-term analysis and if judgment is suspended for as long as possible then rewards are worth the wait. It is important to understand how Pakistan and India see the goals and means of the adversary as actions taken by each side are based on this image of the other side. Pakistan believes that the current right wing Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) government has instinctive hatred against Muslims, and its goal is to balkanize Pakistan and supporting Baloch and Taliban militants are the means to achieve this goal.

India holds a similar mirror image of Pakistan and believes that it is using militants to prevent the rise of India. It is not just paranoia and there is a good amount of evidence that both sides have used proxies for national security goals. However, this simplified assumption is a sign of intellectual laziness that ignores changing dynamics and context of actions of the adversary.

It is extremely hard to understand the mental process of the other side let alone to visualize assumptions and fears of the other side. Both sides never consider that the actions of the other could be generated in response to their own actions. In 1971, India’s active support was instrumental in successful secession of then East Pakistan into independent Bangladesh. In the 1990s, Pakistan used Kashmiri militants to tie down Indian forces in Kashmir that would decrease pressure along Pakistan border. It also supported Sikh militants in Indian Punjab fighting for an independent Sikh state. Pakistani military decision makers of this strategy were young officers during the traumatic days of Pakistan’s humiliating defeat of 1971, and this policy was seen as paying India back in the same coin. India did not view this as Pakistan’s reaction to India’s previous policy of fomenting trouble for Pakistan by assisting its disaffected population but as visceral hostility against India. Now, that India is using Baloch separatists to tie down Pakistani forces in Balochistan is not viewed by Pakistan as a response to Pakistan’s previous policy, but India’s Machiavellian thought process is blamed for this policy. On part of India, current policy is more revenge for past Pakistani misdeeds rather than response to any current Pakistani actions.

India’s own assessment on the ground as well as third parties have good evidence that for almost two decades Pakistan ceased active support of militant organizations operating against India. The major drawback of the mindset of attributing evil designs to the adversary is that many opportunities of reproachment will be missed.

Two cases highlight this dilemma. In 1998, Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee visited Pakistan and in an unprecedented move gave a speech at the national monument. This was a very bold move and a crucial crossroad that could have taken Pakistan and India on a path of peaceful coexistence model. The Pakistan Army could not see the changed dynamics and embarked on an ill planned folly at Kargil heights with disastrous short- and long-term consequences for Pakistan.

In another stunning move, Vajpayee at a significant political risk went for another round and this time with the architect of Kargil operation General Pervez Mussharraf who was now ruling Pakistan, but this effort also failed.

In mid 2000s, Pakistan decided to roll back support of Kashmiri militants; this was done not as a favor to India but was thought to be in the best interest of Pakistan. Despite concrete evidence on the ground India made the same mistake that Pakistan had made in the late 1990s.

This opportunity was not used to take small incremental steps of trying to decrease mistrust. Twenty-five years later, both countries find themselves at the same point of the circle and until the thought process changes, this cycle will continue.

One prevalent misperception is that large events must have large causes. In the last two decades, significant militant attacks occurred in India.

In December 2001 attack on the Parliament in Delhi, in October 2008 the Mumbai attack, in September 2016 on the Indian army base in Uri, in February 2019 the attack on paramilitary soldiers in Pulwama and in April 2025 the attack on tourists in Pahalgam. In all these cases, the result was heightened tension between the two countries, limited conflict resulted, and required international intervention to pull both sides apart. India perceives that the cause of such major events could not be simply that militant organizations acted independently to secure their own interests and now acting independent of former patron. India is not willing to acknowledge that interests of Pakistan and militant organizations are now divergent. On the other hand, Pakistan views that marked escalation and sophistication of attacks on Pakistanis security forces by Baloch militants is due to evil machinations of India with no consideration for alienation of almost all segments of Baloch society. Both countries are now prisoners of this mindset and unable to break free from these ‘mental cages’.

Both sides are also snared in the ‘historical precedent’ trap that limits understanding of changing dynamics of the adversary’s society. In the case of India, the unknown information about the current terrorism incident in Pahalgam is presumed to be the same as known information about historical such incidents when Pakistan was actively supporting Kashmiri militants.

In the case of Pakistan, the historic visit of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee that could have been a turning point in India-Pakistan relations was actively sabotaged by the army by launching Kargil operation in 1999. The conflict between the civilian leadership of that time and the army is not given its due share. The historic precedents could be so powerful and vivid that it is extremely hard to overcome this hurdle. In the case of Pakistan secession of its eastern wing in 1971and increasing and more devastating attacks by Baloch militants on Pakistani security forces and in case of India, Kargil conflict in 1999, Parliament attack in 2001 and Mumbai attack in 2008 are such examples. Over the last decade, there is convergence of India’s problems along Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China and Line of Control (LOC) with Pakistan. It is not the case for the threat of a two front conflict where China and Pakistan coordinate to engage India on both fronts simultaneously but threat of what Indian defense analyst Praveen Sawhney calls an ‘enhanced one front’ conflict.

Pakistan has drifted away from American orbit and is increasingly coming into Chinese orbit. Now, over eighty percent of Pakistani military hardware comes from China. This comes with joint research and training that results in alignment on security and foreign policy subjects over an extended period. Technological advancement of China in all spheres has dramatically improved the quality of weapons platforms but price is significantly lower than western hardware.

Combination of technological advancement and low cost will ensure that defense cooperation between two countries will increase in the coming years. This will not only reinforce the existing Indian mental image but aggravate the fear of Pakistan as now Pakistan is aligned with a more powerful China is a bigger threat than a weak Pakistan alone.

The alternative world view where a modus vivendi with China and Pakistan can provide a powerful economic block consisting of over two billion people is not being considered in India although this aligns more closely with India’s ambitions of an emerging economic power.

On the part of Pakistan, rising economic power of India is viewed through the prism of hegemony. An alternative model could be easily constructed where Pakistan’s strategic location could be viewed through a cooperative economic model rather than a security paradigm, but that item is no where to be seen on the discussion table. India wants to be an economic power to uplift its large population out of poverty and take its place on the world’s stage. Before reaching this goal, it is behaving as it has already achieved that goal that resulted in conflict with almost all its neighbors. Indian leadership is either not aware or simply ignoring the fact that in pursue of multiple goals there are always trade offs and bargains. No country, no matter how powerful, has the luxury to ignore these tradeoffs. The conflict with China and Pakistan is the major impediment in securing India’s economic goals and this fact must be considered in the equation. India and Pakistan overestimate the centralization of each other’s policies and not taking into consideration internal checks. In case of India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his national security advisor Ajit Doval are key architects of national security policy, but the armed forces and the Ministry of Defense Bureaucracies that are instruments of executing these policies have serious problems.

In case of Pakistan, the army is in the driving seat but facing challenges from disaffected opponents in Pakistan Tehreek Insaaf (PTI), ethnic minorities and even current partners like Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PML-N) and Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). It is psychologically uncomfortable for both countries to admit their own weaknesses or failures of policies therefore the fallback position is that the other side must be Machiavellian holding evil designs. When Pakistan decommissioned militant organizations, India perceived it not that the geo-political landscape has dramatically changed after September 11, 2001, and the army realized the folly of their policy but as the result of its own aggressive posture. In 1990’s when India did not aggressively punish Pakistan for its support of Kashmiri militants that were causing significant casualties of Indian security forces, Pakistan did not perceive it as Indian restraint but due to nuclear doctrine of Pakistan that did not exclude first strike. When either country pursues a policy that is desired by the adversary, it is perceived as due to the strength of one’s own policy rather than independent policy decision of the other side. However, on the other hand, if a party does not behave as expected, the adversary perceives it as due to evil designs and not as a response to one’s own policies. Both sides view success as the result of their own actions, but their failures are not due to their own actions. This is the reason that they are unable to break free from the vicious cycle and look at other available alternatives.

Decision makers do not have the luxury of the knowledge of the historian therefore they overestimate their own potency. Both countries will likely evaluate the current crisis through this ‘potency paradigm’. India will view that Pakistan did not escalate because of India’s strength and Pakistan could have done more harm if India did not act in this manner. Pakistani assessment will be the mirror image thinking that India’s original plan was more aggressive, but Pakistan’s actions prevented it. Pakistan was ready to accept the downing of Indian jets as victory and not go for any retaliatory measures. If leaders think that their own strength achieved the desired result, they will not be inclined to cooperate or give incentives to the adversary. If this perception is reinforced, then the country will overreach, and this happened with Indian decision to cross another threshold by directly attacking Pakistani air bases.

In this decision, we also see how events dictate actions that were not on the table in the original script. The unexpected downing of several Indian aircrafts by Pakistani defensive measures created a new situation where India had to go for another round to placate domestic audience that was suffering from the war fever. The fact that aircrafts were downed meant that the measure had to be against the Pakistan Air Force.

Sending aircraft into Pakistani territory was out of question, therefore next logical move was to hit airbases to convince the Indian public that revenge has been taken. The mistake that India made was that in addition to some remote small bases, it hit a strategic air base that is alleged to store nuclear weapons. Pakistan viewed it as crossing the red line and decision was now made to retaliate by targeting Indian bases that was not part of the earlier Pakistani decision.

Pakistan communicated to the international community that set off the fire alarm in Washington that forced the ceasefire within hours. Policy makers are consumers of intelligence and if political leadership is already selling a product to the public, neither the individual analyst nor the organization will risk their career and reputation, and the circle of incomplete information is completed with assumption.

Both countries are cognizant of the ground reality that there are limits to escalation under the nuclear umbrella and action on both sides will be very calibrated and restrained. It is likely that climbing will be a cautious one step up and then quick descent but there is always the risk of things going the wrong way due to overreach, incompetence, ignorance, or a mistake. In the current scenario, the background of extreme mistrust and anger and absence of a robust back channel increases the risk of such mishap. This fact alone should be a sobering thought for both sides and the minimum requirement is establishment of a permanent back channel at high level that can be useful in crisis situations.

There is deep mistrust on both sides but contrary to widely held belief, the history of both countries tells us that blood lust is not as deep as it seems. A comparison with recent conflicts can clarify this point. In the last seventy years, in all the conflicts between the two countries with a population of over one billion, the total casualties have been a few thousand only. In the current crisis, the total number of people killed on both sides is less than sixty. In contrast, in recent conflict between Russia with a population of one hundred and forty million and Ukraine with a population of thirtyseven million, a conservative estimate of casualties is one million.

In the most recent cycle of violence between Israel with Jewish population of seven million and Palestinian population of five million, the total number killed is over sixty thousand. Maybe this is the ray of hope that if both sides can overcome the ‘mindset’, they can find alternative ways that addresses their basic need for security without reliance solely on coercive means.

Current attitude of India and Pakistan towards each other is best expressed in a German phrase ‘Schadenfreude’ meaning one gets pleasure and satisfaction from the misery and suffering of the other.

In my view, this is the most dangerous trait and if not contained it can increase the likelihood of both countries using proxies to inflict pain on the opposing side as a major plank of national security policy. Unless both sides can work to change this negative mindset, they will hand over the conflict to now the fifth generation since independence in 1947. This challenging task is the responsibility of both societies and no outsider, no matter how well meaning, can help them in this regard.

A better understanding of psychological factors in decision making process can help both countries as well as third parties engaged with the region. National security is a much larger canvas, and military means is just one tool that usually has limited returns. A realistic approach is for small incremental measures such as easing visa restrictions, allowing religious pilgrimage, cultural and sports activities, etc. This should be complemented with allowing a debate within their own societies to talk about alternative approaches.

It is a low-cost approach that creates the environment for listening to other narratives. There is old Quaker saying that ‘the enemy is the one whose story we have not heard’.

“Everything in your life reflects a choice you have made. If you want a different result, make a different choice.”

Acknowledgements: Author thanks a number of well-informed individuals from India, Pakistan and third parties who candidly shared their views. All errors and omissions are the author’s sole responsibility.