Glaciers worldwide are melting at unprecedented rates, with some disappearing so quickly that entire river systems are at risk of collapse. The year 2025 is declared as the International Glaciers Year to create awareness and promote the preservation of glaciers. Natural hazards in the cryosphere are increasing, and nations with emerging economies have limited resources, infrastructure, and adaptive capacity to adapt to climate change. There are several natural phenomena in the cryosphere, like ice melt, glacier surge, permafrost thawing, glacier retreat, decreasing snow cover, and sea ice loss.

Due to climate change, these activities are occurring dramatically and at an alarming pace, which requires immediate and effective actions to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions and the implementation of climate protection agreements.

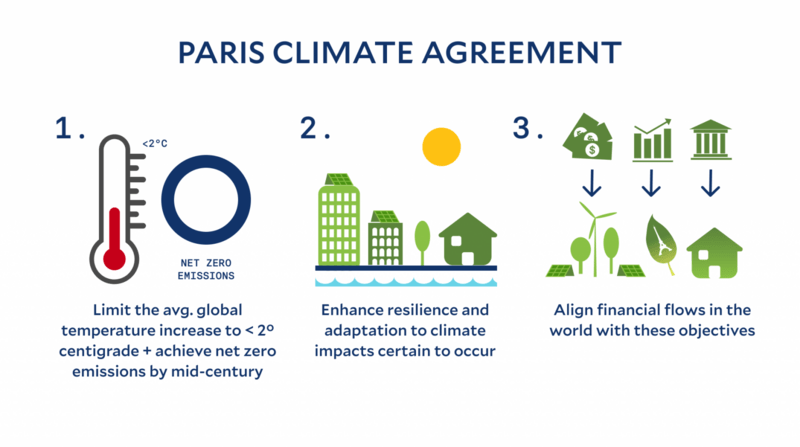

According to a report by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative on the state of the Cryosphere and Global Damage in 2024, Current climate commitments known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), are likely to exceed the Paris Agreement’s 2°C limit. If high carbon emissions continue for the rest of the century, we won’t meet even these inadequate targets. To address this, immediate actions are needed to return to the 1.5°C limit.

Despite emitting less than 1% of global carbon dioxide, Pakistan ranks among the top 10 countries suffering from climate-related impacts. This reflects a broader climate injustice. Developed countries, particularly in the West, became wealthy through centuries of industrial activity that pumped greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

The resulting global warming now threatens the entire planet, yet the burden of mitigation is often shifted to developing countries that had little role in causing the problem. This injustice has disrupted the natural climate balance. The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) suggests that as income rises, pollution initially increases but eventually declines. However, this model falters today as developing countries are pressured to adopt clean technologies before achieving the wealth needed to afford them.

Pakistan, for instance, must choose between cheap coal power or expensive solar alternatives, all while incurring over $30 billion annually in climate-related losses. Rich nations demand that Pakistan “go green” without enough funding/tech transfers.

Recently, the U.S. announced its exit from the Paris agreement, indicating increased investment in fossil fuels, worsening environmental conditions. Instead of controlling their carbon emissions and aiding developing countries with financial and technological support, the opposite trend is occurring. Some wealthy countries may underestimate climate risks due to perceived short-term gains, as some regions are experiencing short-term benefits from warming temperatures. For instance, Siberia could emerge as a major wheat producer, and Canada may see a boom in wine production.

Arctic ice melt is opening up shipping routes 30–50% shorter than traditional passages, reducing travel time and emissions. Greenland’s retreating glaciers are releasing valuable sediment, though dredging poses environmental risks. The retreat of glaciers produces nutrient-rich glacial rock flour, enhancing plant growth and boosting barley yields in Denmark by 30%, allowing farmers to sell carbon credits for the CO2 absorbed.

Decreased sea ice reveals ancient artifacts, providing archaeologists access to cultural history. In Norway, melting ice has uncovered an ancient mountain pass and remnants from the Roman Iron Age and Viking era. while melting permafrost in the Arctic reveals ancient microbes with medical potential. Yet these gains are marginal and unevenly distributed, offering little solace to vulnerable populations in the Global South.

Rich nations are not immune to climate effects. The Climate Risk Index Report 2025 found that seven of the ten most affected countries in 2022 were high-income nations, showing that wealth does not protect against climate impacts. In 2024, there were about 151 unprecedented disasters. For example, California’s 2023 wildfires burned over 4 million acres and affected 70 million people.

Canada is facing increased wildfires, pest outbreaks, and unpredictable growing conditions. Italy suffered severe floods, and Vermont’s capital experienced historic flooding. Coastal cities such as New York and Miami are increasingly at risk from storm surges and rising sea levels, with 12.6 million properties vulnerable to flooding. The cryosphere’s degradation is not only an environmental issue but a humanitarian one. In 2024 alone, extreme weather events displaced over 800,000 people globally.

Climate disasters in South Asia have resulted in $706 billion in losses globally from 2000 to 2025, with Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh being the hardest hit. The Himalayan region, often referred to as the Third Pole, is particularly vulnerable. The Himalayas feed major rivers that sustain billions. Glacier retreat is disrupting seasonal water flows, causing floods during melt periods and droughts in the dry season.

In Pakistan, instability in the cryosphere endangers 7 million people in northern regions. Glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs), water shortages, and agricultural disruption are becoming common. Temperature fluctuations are destabilizing snowpacks, triggering avalanches in Gilgit-Baltistan, Kashmir, and Nepal. Their vulnerability is manifold due to remoteness, underdevelopment, and limited disaster recovery mechanisms.

Climate change has also intensified water disputes in the region, such as those over the Indus and Teesta rivers. With 67% of glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau projected to disappear by 2100, tensions may further escalate as water scarcity worsens. There is no time to wait for assistance from the West; South Asian countries must act now by formulating regional strategies for climate adaptation and resilience. The Indus River Basin should be at the heart of this plan; the increased influence of China in the region can bring all nations to the table for reconciliation and collaboration for mitigating the drastic impacts of climate change, especially on the cryosphere.

Organizations such as the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) should create effective climate policies and exert pressure on rich countries for meaningful advancements in trade and technology.

Developed nations need to end the practice of selling redundant technologies with harmful impacts on the environment to developing nations. Also, the strategy of imposing sanctions and tariffs on developing nations for violating climate agreements only worsens their limited growth. Ultimately, the entire world is at risk and blaming or controlling low-income countries will not resolve the crisis.

China, which possesses significant technological and financial resources, must lead in transferring climate-safe technologies, supporting early warning systems, and helping to build adaptive capacity in the high mountains.

Most critically, Pakistan and other developing countries need to prioritize indigenous policy responses that integrate local knowledge, environmental science, and community-led action to protect their people and ecosystems.

For example, in Gilgit-Baltistan, people are building ice stupas (artificial glaciers) to conserve water in winters and use it in summers. Climate funds must be utilized to support these indigenous practices, the study of glaciers, and the installation of early warning systems.