Pakistan army’s prodigal son Major Agha Humayun Amin passed away on 21 February 2025 after a brief illness from complications of cancer.

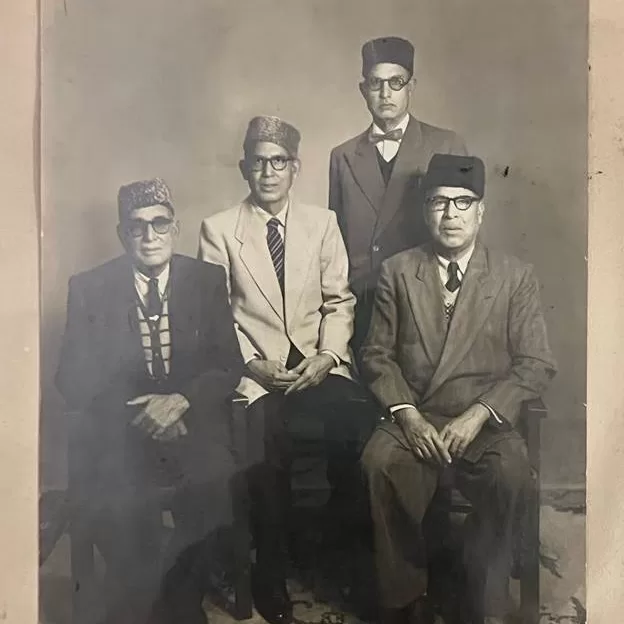

Major Agha Humayun Amin was from a military family and his ancestors served the Raj dating back to the late nineteenth century. His great-grandfather Faiz Baksh was from Aligarh and served in the Indian police service, he had married an Afghan lady Abadi Begum and lived in Faiz Manzal in Delhi. He retired around 1915 and died in 1920, he had four sons. Agha Abdur Rauf also joined the Indian police service and in 1947 decided to stay back in India. He served as Superintendent of Police (SP) Gorakhpur. He sent his son Agha Manzoor Rauf to Pakistan who joined the 8th Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) Long Course, and on commission joined Corps of Engineers. He retired as Major General. Abdur Rauf came to Pakistan in 1972 to stay with his son and died in 1981. Abdul Sami also joined the Indian police service and served as Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Meerut. He migrated to Pakistan and served as SP Karachi. Abdus Samad completed his medical degree from Lucknow. Details are not clear, but he ended up as personal physician of King Zahir Shah of Afghanistan, most likely sent by the British to keep a close eye on the royal house. He was at the King’s side in Kabul as well as in Gardez where the King spent his winter. On return from Kabul, he joined the Indian Medical Service.

Agha’s grandfather Muhammad Amin served in the Ministry of Defense, migrated to Pakistan and retired as Deputy Secretary Defense. Agha’s father Agha Humayun completed his engineering education and then joined the Pakistan Army and seniority with 11th PMA course. He is from the Corps of Engineers and retired at Brigadier rank. He is credited with the conversion of the jeep track from Gilgit to Skardu with metaled road for all kinds of traffic, constructing of a dozen bridges over the Indus in the most hostile terrain.

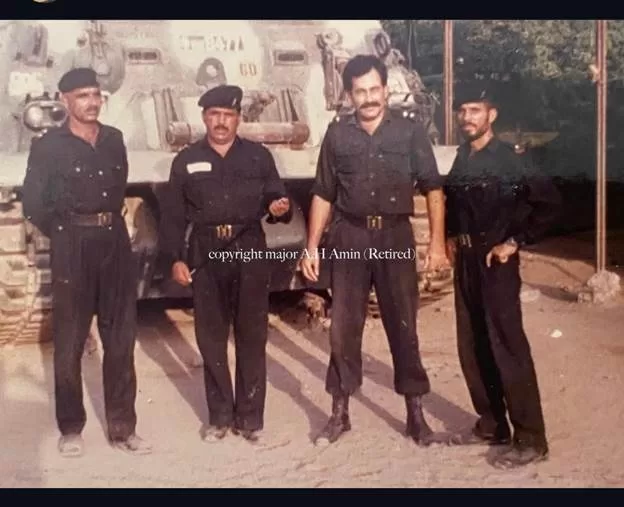

Agha joined 67th PMA Long Course and was commissioned in May 1983 in the elite 11 Prince Albert Victor’s Own (PAVO) Cavalry. He was not a run-ofthe-mill officer and had not joined the army as a secure job. His family was well off and he lived a good life driving a Mercedes car as a young captain.

In 1985, with barely two years of service at the rank Captain, he had put in his resignation, but the Commanding Officer did not forward it to General Head Quarters (GHQ). Agha walked into his Acting Brigade Commander Brigadier K. M. Nasir’s (brother of former DGISI Lieutenant General Javed Nasir) office to appraise him of his resignation not being forwarded. Nasir spent an hour with him and persuaded him to withdraw his resignation. Nasir assessed him as a gifted officer and became his lifelong friend. Agha was a restless soul and always had problems with authority and this is the reason he was constantly moved, and he ended up serving with 29 Cavalry, 58 Cavalry, 15 Lancers, 14 Lancers and 15 SP. Someone in the Military Secretary branch came up with the right idea to give Agha command of an independent tank squadron and according to him, this was his best time in the army. Agha finally said goodbye to the army in 1994.

Agha was a historian, and he wrote extensively on the history of the Pakistan army. He did not mince his words and always wrote what he thought, he criticized the army’s decision-making process and operational blunders, this made him persona non grata in many circles. However, several officers had great respect for his historical knowledge even if they disagreed with his conclusions. Many a time his criticism seems excessive and even with a touch of bitterness, but Agha had clarified his position and in his own words in October 2009 at the height of the terrorism menace in Pakistan stating ‘this is not criticism. I am not a paid journalist. This is a call for reflection. Serious reflection and serious inner thinking that may be the spur to serious reorganization in the Pakistan Military. The enemy is not in Waziristan or Afghanistan. The enemy is our own damn inefficiency and complacency. It merits serious thinking at all plains; tactical, operational and strategic.”

My personal interaction with him started about two decades ago when he was assistant editor of the Defence Journal. I had written a letter to the Editor and over the next year after many conversations and correspondence, he found my interest in the history of the Raj army and convinced me to write regularly for the journal. In this sense, I owe my writing adventure to him. Over the years, we talked about many things and discussed military history of the Raj, Indian and Pakistan armies and current conflict of the region. Whenever in doubt about any arcane historical fact, Agha’s encyclopedic knowledge came to my rescue.

In many circles, he was persona non grata as he always spoke his mind and officers felt uncomfortable. However, I was surprised to see that several officers had great respect for him despite the disagreements. He introduced me to several Pakistan army officers in operational and intelligence arenas that helped me to understand the nuances of a prolonged and complex conflict. I got educated and enlightened by this exercise.

He was based in Afghanistan for several years working as sub-contractor for power transmission lines construction. He had the unique opportunity to work in all thirty-four provinces of Afghanistan and spent some time in the Iranian port city of Chabahar. I personally do not know even an Afghan who has lived and worked in all provinces of the country. Agha Amin had his fingers on the pulse due to his presence on the ground. We shared our perspectives where he provided insights of the Afghan theatre while my focus was mainly on the Pakistan side. This helped me understand the threads connecting areas on both sides of the Durand Line. We had disagreements about many aspects but respected each other’s point. One of his last stints was to help the Spanish government extricate some Afghans who had worked with Spanish forces after withdrawal of the Americans from Afghanistan. He had a wide range of Afghan friends including former communist officers, Pushtun, Tajik and Uzbek government officials and academics including the late Professor Rasul Amin.

Agha was a restless soul and described himself as a wanderer of the ‘philosophical wilderness’. He hated conformism and had broken all the molds and declared that “I’m not interested in nationalism or any organized religion”. In the later part of his life, he had let his hair and beard grow and had an uncanny resemblance to Karl Marx and Rabindra Nath Tagore. I wondered if he would be a good candidate for the movie about these two characters although for the role of Karl Marx, he would have to gain a few more pounds while playing the role of Tagore, he would have to lose a few pounds. During my trips to Pakistan, we had some interesting moments of laugh as we roamed around in cantonment and sometimes met at the army services mess. Sentries were at full alert looking at Agha’s long hair and full bushy beard. He would chat with them with caring and encouraging words, bringing smiles on their face.

My driver had given me a red cap as gift that was usually used by Pushtun Tahaffuz Movement protestors. I was stopped at almost every checkpoint in cantonments but after a friendly chat everybody relaxed. In the last few weeks of his life, he shared all his medical reports and I concluded that he was at the end of his journey in this world. I called him the prodigal son of the Pakistan army and the army took care of its son, he spent the last days of his life in Combined Military Hospital Rawalpindi and Lahore.

My last text to him a few days before his death was “pleasure and honor is mine of knowing a gem of a person like you. Pakistan and its army do not produce eccentrics like you anymore. Stay blessed”.