The rise of extremist ideas in Indian domestic politics under the Modi government has shaken New Delhi’s constitutional foundations and its manifestations in the country’s foreign relations. The arrival of Modi in Indian politics as Prime Minister augmented the role of religion in the country’s politics based on the fanatical ideological configurations of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its strong association with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The common extremist beliefs of both ideological groups revolutionised the conventional notion of Hindu nationalism in India’s mainstream social, economic, and political landscapes.

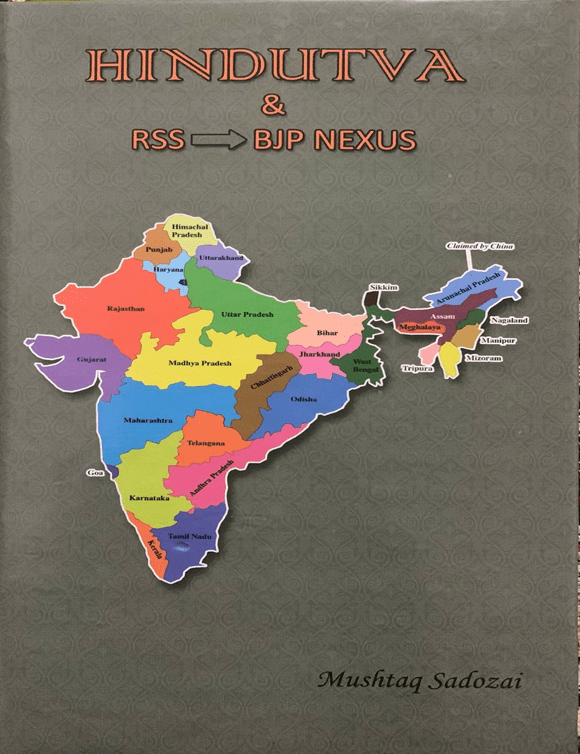

While this scenario attracted the intellectual circles of the international academic community towards India it resulted in the emergence of a brief literature concerning the changing attributes of New Delhi’s altered approaches for managing simultaneously internal and external politics with the strong support of extremist religious forces. In this existing literature about the changing ideological dynamics of Indian politics under strict religious values, Mushtaq Sadozai’s book under review sheds light on the impact of the RSS-BJP nexus on the broader Indian politics and on the South Asian regional security environment. The book’s central theme is divided into eighteen short chapters, the debate starting from the genesis of Hindu-Muslim rivalry in the subcontinent which forced the Muslim community to formalize their voices for religious freedom under the Two-Nation Theory.

The philosophical description of the Two-Nation Theory and its inseparable association with the historical freedom movement of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent starts from the Muhammad Bin Qasim era (P18).

Further historical exploration by the book’s author underlined various complications of the subcontinent’s politics in which debates on Gandhi’s role as a key religious leader or a leading proponent of secular ideology and the emergence of Hindu fundamentalist thoughts in the country’s mainstream political culture are treated as the prominent regional development of South Asian partitioned subcontinent.

In the subsequent chapters the debate underlined the birth of Hindutva and RSS in Indian domestic politics and its transformation into the country’s mainstream foreign relations parallel to jeopardizing the status of Muslim minorities in India.

New Delhi’s formal opposition to the creation of Pakistan and its initial leadership’s decision to adopt a multileveled anti-Muslim narrative and its countrywide promotion served to complicate Indian domestic politics, which then resulted in numerous Hindu-Muslim riots in India, according to the author’s historical survey presented in book’s ten chapters.

Sadozai argues that this ideological shift has contributed to internal polarisation within India and heightened tensions in the region based on the fanatical Hindu ideology. The discussion on the latest developments starts in chapter eleven, where the author underlined the tragic incident of Indian history in the form of the Gujrat riots under Narendra Modi’s term as Chief Minister.

Thereafter the mentioning of the Indian court’s actions against Modi was proof of the formal reluctance of Modi to prevent Hindu-Muslim violence from Gujrat and its alleged involvement in this communal bloodshed, which validated the book’s core argument.

Furthermore, recent developments in the form of the revocation of Article 370 and New Delhi’s consistent attack on regional cricket diplomacy further proved the Modi government’s determination to continue its anti-Muslim policies for the Muslim community living inside India and the occupied Kashmiri areas.

The promotion of wider antipathy toward the Muslim community served to cause a massive wave of human rights abuses in Kashmir, which several independent research institutions and latest reports of major Human Rights organisations have reported impartially.

Based on the above descriptions, it is appropriate to maintain that the book’s author highlights the contemporary status of New Delhi in promoting strict religious policies against several indigenous minorities, where the prime target of Mod’s religious ideas is the Muslim population.

The author’s pragmatic approach and rational analysis makes the book’s primary debate rationally convincing and impartially logical due to the inclusion of factual evidence in his argument.

In this way, the arguments covering different perspectives of New Delhi’s contemporary anti-Muslim narrative laced with several legislative measures of the Modi government proved the substantial impact of Hindutva ideology on India’s foreign policy and its inseparable relationships with neighbouring countries.

The effects on territorially adjoining nations have intensified the scope of peace, development and stability in the broader South Asian regional politics.

While keeping in mind the BJP’s dominance in Indian domestic politics and the growing attention of the global intellectual community towards the increasing violation of minority rights under the Modi government, Sadozai’s book addresses a highly important topic of contemporary South Asia which could be treated as an appropriate reading for people interesting in understanding the deteriorating values of peace and stability in the South Asian region.

Moreover, the academic, policymaking, journalist, and diplomatic community could find this book very interesting in understanding the overwhelming impacts of fanatical Hindu ideology on India and its unquestionable regional implications.