Trial

The Koran often says that God measures out good and mercy to test people’s faith and to allow people to prove their own nature—not to God, of course, because he already knows their nature. They are demonstrating their nature to themselves so that they will have no objections when they reach their destination in the next world.[1] People who have faith in the measuring out—both the good of it and the evil of it—will recognize that God knows what he is doing, even if their personal desires are constantly thwarted. They will show their gratitude to God when he gives and they will have patience when he withholds. Such reactions will prove their faith.

But they will not have demonstrated faith if they act in the way that the Koran repeatedly stigmatizes (employing words such as good and evil, mercy and wrath): “When We bless the human being he turns away and keeps aloof, but when evil touches him, he is in despair” (17:83). The proper response to good, mercy, and blessing is gratitude, while the proper response to evil, wrath, and harm is patience and hope. When the Koran takes the benefits of both good and evil into account, it sometimes employs the words trial (bala’) and testing (fitna): “We try you with evil and good as a testing, and then unto Us you shall be returned” (21:35).

The Koran says that human beings have been placed in the earth to prove themselves, to show their stuff. Once they have undergone the test, their final resting place will be known to everyone:

We split them up in the earth into nations, some of them wholesome, and some of them otherwise; and We tried them with the beautiful things and the ugly, that perhaps they should return [to tawhid]. (7:168)

Surely We will try you with something of fear and hunger, and diminution of goods and lives and fruits. Yet, give good news to the patient who, when visited by an affliction, say, “Surely we belong to God, and to Him we return.” (2:155)

Trial does not involve only evil, pain, and suffering. Benefits and pleasure are also trials. If people forget God whether in suffering or joy, they have failed the test. And even remembering God must take the right form. Simply recognizing God’s gifts is not sufficient. Gratitude (shukr), after all is inseparable from faith (iman), and faith demands submission to the Shariah. In the following, the Koran criticizes people for failing both the test of blessing and the test of affliction.

Notice how the passage immediately turns to a criticism of those who fail the test by listing various wholesome deeds that they need to perform in order to demonstrate their faith:

As for the human being, when his Lord tries him, and honors him, and blesses him, he says “My Lord has honored me.” But when He tries him and stints his provision, he says, “My Lord has despised me.” No indeed, but you honor not the orphan, and you urge not the feeding of the needy, and you devour the inheritance greedily, and you love wealth with an ardent love. (89:15-19)

God tests human beings to find out which of them have faith and do wholesome deeds and which of them conceal the truth and work corruption:

We have appointed all that is on the earth as an adornment for it, and that We may try them, which of them is most beautiful in works. (18:7)

Blessed is He . . . who created death and life, that He may try you, which of you is most beautiful in works. (67:2)

One of the recurring themes of the Koran alluded to in the above verses is that people fail to acknowledge their own proper places. If they experience good, they think they deserve it, but if they experience evil—that is, lack of good—they think they are being mistreated. This is kufr (truth-concealing and ingratitude), since it contradicts the necessities of both faith and gratitude:

When harm touches the human being, he calls upon Us. Then, when we confer on him a blessing, he says, “I was given it only because of a knowledge.” No, it is a trial, but most of them know not. (39:49)

Tawhid means that people have nothing positive that is strictly their own; on the contrary, all good is in God’s hands. If people experience good, they experience it on God’s initiative through no merit of their own. If they do not experience good, that is simply what they deserve, since—apart from God’s blessing and mercy—they are literally nothing. Hence, the Koran pictures human pretensions to good as distortions of the way things are.

No one is hurt, however, by human pretensions, except those who make the pretensions. Justice (`adl) is a divine attribute, defined as putting a thing in its proper place. The usual opposite of `adl is zulm, which in the Koranic context we translate as “wrongdoing.” Wrongdoing is a human attribute, usually defined as putting a thing in the wrong place.

The Koran repeatedly stigmatizes human wrongdoing. Interestingly, when it mentions those who are harmed by the wrongdoing, it almost always employs the word self (nafs). People cannot wrong God. A mosquito cannot sting the sun. But people can and do wrong themselves every time they put something in the wrong place. They distort their own natures, and they lead themselves astray. The following is a typical verse in which wrongdoing is mentioned. It occurs in a story of the destruction of earlier peoples who denied their prophets. Remember that a god is anything that is served or worshiped other than God. The ultimate wrongdoing is shirk, to serve things that are not worthy of service, to put false divinities in place of God.

And We wronged them not, but they wronged themselves. The gods that they called upon apart from God were of no use to them when the command of your Lord came. The gods increased them only in destruction. (11:101)

Faith in the measuring out means to understand that all good belongs to God. Everything other than God is lacking in good in some or many respects. People who have such faith will be grateful for the good they have, and they will trust God in respect of the good that they lack. They will be confident that the Real, who is the Merciful, measures things out with wisdom while keeping the ultimate good of all things in view: When evil touches him, he is in despair. (17:83)

Those who have kufr toward God’s signs and the encounter with Him–they have lost hope in My mercy, and there awaits for them a painful chastisement. (29:23)

Do they not know that God outspreads His provision to whomsoever He will, and straitens it? Surely in that are signs for a people who have faith. Say: O My servants who have been immoderate against yourselves, do not despair of God’s mercy! Surely God forgives all sins. Surely He is the Forgiving, the Compassionate. (39:52-53)

Brief statements of the measuring out always suggest a logical contradiction: If all things, whether good and evil are measured out, then is it not true that our business is over and done with? After all, the Prophet said that a person’s ultimate abode—paradise or hell—is already written for him in his mother’s womb. Therefore, what use is religion, since everything is already decided?

This is the issue of free will and predestination, a problem that has vexed theologians of various religious persuasions for centuries. We will not present the Muslim theological solutions to this problem, though many have been proposed. Instead, we will simply stick to the Koranic level of things and suggest that, as in the case of all-important problems, there is no clear and simple answer. Just as often as the Koran affirms that God has measured things out and that he knows all things even before they occur, it also affirms that human effort is meaningful:

Whoso desires the next world and strives after it as he should while having faith—those, their striving shall be thanked. (17:19)

The human being will have only what he has strived for, and his striving will be seen. (53:39)

The Koran is nothing if not a book of exhortations directed at people to get them striving on the path to God. Just as it demands a voluntary Islam over and above universal and compulsory Islam, so also it demands jihad and mujahada—struggle in the path of God. If human beings were mere puppets, with no self-control whatsoever, the Koran would be a silly book, since it would be telling stones to fly.

Free will and predestination need to be understood as complementary expressions of the human situation. Neither explains the situation fully. One useful way to understand how the two ideas are related is to think again in terms of Tanzih[2] and Tashbih[3]

In respect of tanzih, human reality is sheer unreality, since God is the only reality there is. Human beings have no knowledge, power, desire, or freedom, since these are divine attributes and belong exclusively to God. But in respect of tashbih, human beings reflect these divine attributes. The attributes belong to God, but they are put into effect through human beings. If God can “do whatever He desires,” so also, in respect of tashbih, human beings can do whatever they desire.

In any case, human freedom has enormous limitations, as everyone recognizes. People cannot choose their place of birth, their parents, their race, their culture, their mother language, their fundamental physical characteristics, and so on.

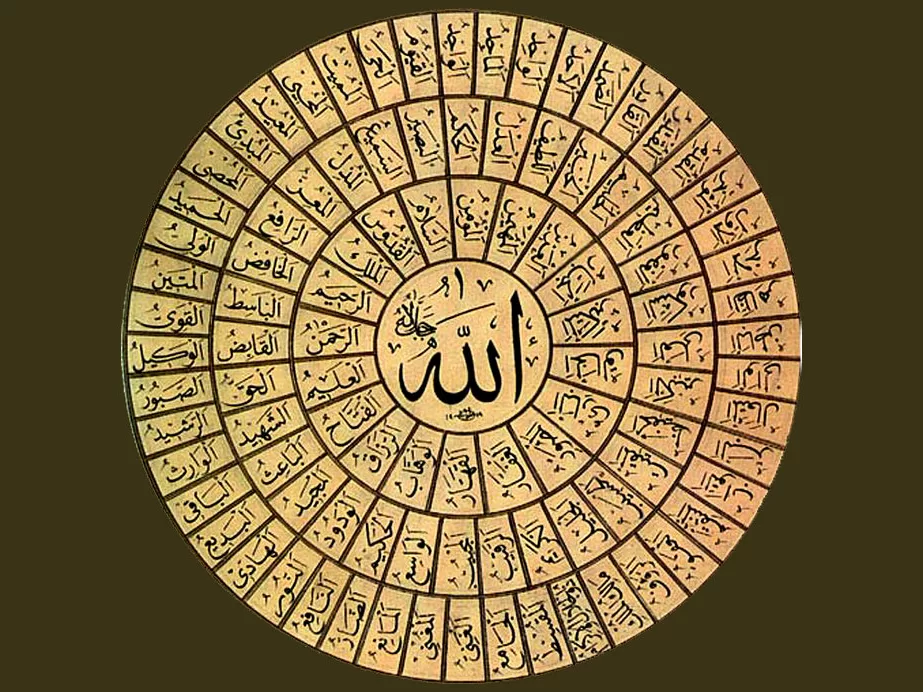

All these are givens. But within the context of these givens, choices remain. To the extent that these choices are real, people are free. Notice that predestination pertains to the side of tanzih and the attributes of wrath. One of the most important theological terms employed to refer to predestination is jabr (compulsion), and one of God’s Koranic names is al-jabbar, (All-Compeller). This name fits into the category of majestic and severe names but we know that God’s mercy takes precedence over his wrath.

The names of beauty and gentleness will overcome the names of majesty and severity. Love and mercy will conquer compulsion. The beautiful names bring about nearness to God, and the closer people are to God, the more they share in his freedom.

In modern society we think highly of freedom and consider it a worthy goal in life. Of course there are two basic modes of freedom, “freedom from” and “freedom for.” We want freedom from oppression, and we want freedom for speech and for the things that we enjoy. In human affairs, these two kinds of freedom often conflict. When we gain freedom to enjoy a wealth of consumer goods, for example, we may bring about terrible oppression for peoples in other parts of the globe who have to suffer the consequences of exploitation and ecological devastation.

The flip side of freedom’s coin may well be slavery. What is good for you may be evil for someone else. Your freedom can be another’s slavery, or it can even be your own slavery. Look at all the people who, in their desire to be free to have a good time, enslave themselves to demeaning jobs.

Muslim thinkers also take into account both freedom from and freedom for. Their concept of freedom is distinguished from the modern concept because it is rooted in the Shahadah.

“There is none free but God.” God is free of any sort of outside constraint, “a sovereign doer of what He desires” (11:107, 85:16)

but no creature can have this attribute. Compared to God, all creatures dwell in utter slavery. In order for human beings to be free, they must partake of God’s freedom.

God is free of everything other than himself. He is “independent of all the worlds” (3:97)

Human beings can never be free of God.

“O people, you are dependent upon God, and God is Independent, Praiseworthy” (35:15)

All power, reality, and praise belong to God alone. Since human beings can never be free of God—they are Muslims and `abds by nature— they need to recognize this and submit to him voluntarily. Then they will not be flying in the face of reality. Submitting themselves to God, they free themselves from everything other than God. Freeing themselves up for God, they become free from everything else.

To be free from everything other than God is to be free from all unreality and to be free for Reality. It is to reject every form of shirk and establish tawhid. Hence, in the Islamic view, “freedom from” is to be free from the constraints placed on us by created things and to serve God. “Freedom for” is to choose the Real over the unreal in every case. To be free for the unreal is meaningless, because the unreal does not exist.

People should desire to be free for knowledge, desire, power, good, and everything positive and real. Nothing is real but the Real. Hence freedom from the unreal comes down to the same as freedom for the Real. There can be no contradiction. Both are tawhid. Are we free? The answer is, “Yes and no.” We are free to the extent that we are similar to God, but our similarity is always tempered by incomparability. Tawhid demands both tanzih and tashbih.

Freedom is a reality, and it is a reality that has degrees. The closer people move to God, the freer they become. The purpose of Islam is to show the way to tawhid, where tanzih and tashbih dwell in proper balance. To be human is to be relatively free.

But to be as free as it is humanly possible to be free can only come about when full submission and surrender to Reality is achieved. One final point needs to be made on the issue of free will and predestination:

When people criticize the contradictions involved in attributing absolute power to God, it is important to keep in mind their intentions; in other words, we have to ask why people object. Often the intention is simply to convince others that they are stupid and naive to think that the idea of God or prophetic guidance has any meaning

To use some modern jargon, when people protest against the idea of predestination, they are often motivated by hermeneutics of suspicion. The protesters assume the worst. In their view, the real issue is power.

They think that what has really happened is that certain people have manipulated religious teachings in order to preserve their own power and keep others subjugated.

Without denying that there may be such manipulative people, we still have to recognize that there are other ways of reading the situation, and that the Islamic way has always been rooted in hermeneutics of trust.

This trust is not directed at human beings, however, but at God. The Koran speaks of trust (tawakkul) in forty verses, and in every case the object is God.

God is their Friend, so in God let the faithful put their trust. (3:122)

Truly, I have put my trust in God, my Lord and your Lord. There is no creature that crawls, but He takes it by the forelock. Surely my Lord is on a straight path. (11:56)

Judgment belongs to none but God. In Him I have put my trust, and in Him let all who put their trust put their trust. (12:67)

And whosoever puts his trust in God, He shall suffice him. (65:3)

Satan has no authority over those who have faith and put their trust in their Lord. (16:99)

A famous hadith qudsi suggests that trust in God means that people should always have a good opinion of him. They should never be suspicious of God’s motives: “I am with My servant’s opinion of Me,” so they should have a good opinion of him so that they will meet him inasmuch as he is Merciful, Loving, and Gentle. Muslims have a good opinion of God because they recognize that he is the Real, and that reality itself demands that mercy must predominate over wrath. They have always held that God’s good intentions in revealing the Koran are clear. He wants to guide people to ultimate happiness, or to the fulfillment of human destiny. By asserting that all things are measured out, the Koran is simply stating that God is in charge—or that Reality is what it is—and nothing can be done to change it. Among the things that God measures out are freedom and guidance.

Hence, human beings are free to accept or reject the offered guidance. They carry a burden of responsibility: they will be called to answer for how they employed the freedom that they were given and how they reacted to the guidance that they were offered. This is also the limit of their responsibility. To the extent that they were not free and guidance was not offered to them, they will not be held responsible.[4]

To be continued ……

Book Reference: Vision of Islam[5]

https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX1vSIkpt5ir0ku4Z6JpYe1DOKRhZ0bQvAHfWIlEMwoJCgvBO4jrS3u3I7inyMZPCtsLGxtuDDrNR5o2Qz/pub

[1] “The Vision of Islam” authored by Dr. Sachiko Murata and Dr. William C. Chittick delves into the multifaceted aspects of Islam.

[2] https://defencejournal.com/2024/10/10/the-visionof-islam-9/

[3] https://defencejournal.com/2024/11/10/the-visionof-islam-10/

[4] This is why most Muslim theologians maintain that anyone who has not heard a prophetic message is not responsible to follow a Shariah;

[5] Islam of Vision اردو ترجمہ مکمل کتاب : http://www.williamcchittick.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Chittick-and-Murata-Vision-of-Islam-Urdu-Translation-by-Muhammad-Suheyl-Umar. pdf