Is global warming speeding up? The year 2023-2024 has emerged as a defining moment for the climate crisis, shattering records by hitting a milestone in both years and exposing humanity’s vulnerabilities. Global temperatures surpassed the 1.5°C threshold of the Paris Agreement, marking a bleak milestone that has intensified the scale of climate-related disasters. From unprecedented heatwaves and devastating floods to the rapid melting of glaciers, the Anthropocene era has become a stark reality. This unfolding crisis not only threatens ecosystems and human livelihoods but also poses a threat to cultural heritage and community identities. The escalating climate extremes due to human activities result in relentless harm globally especially in developing countries like Pakistan.

Our unpreparedness to address these climate challenges is evident. As global leaders convened to deliberate on climate justice and international courts weighed in on state responsibilities, the urgency to transition from negotiation to action has never been so great. It is time to call for pragmatic, collaborative approaches to safeguard our planet and its cultural legacy.

A Year in Review

The World Meteorological Organization declared 2024 as the warmest year on record according to the six global datasets used. It has broken the record of 2023 in all areas and unleashed the doors of hell on most of the vulnerable communities as global annual mean near-surface temperatures reached 1.36 °C above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average in 2023, whereas, during the whole of 2024, the planet breached the 1.5°C threshold limit. All the real-time data locations indicated the highest Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) emission ever recorded; the United Nations Environment Program’s flagship Emission Gap Report 2024 quoted 57.1 GtCO2 emitted in 2023 alone.

In the past 12 months of 2024, extreme weather events have surged due to a 9% increase in atmospheric moisture holding capacity and fire weather conditions added on average 41 additional days of dangerous heat in 2024, characterized by relentless heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, storms, and floods. These catastrophic conditions have contributed to the deaths of at least 3,700 people and have forcibly displaced millions, as reported by World Weather Attribution.

Planet Earth also experienced consecutive nine warmest years on record between 2015-2024 in all meteorological datasets. Atmospheric concentrations of the three major greenhouse gases reached new records of 417.9 parts per million (ppm) for Carbon dioxide (CO2), 1923 parts per billion (ppb) of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) at 335.8 ppb, respectively, which are 150, 264 and 124 per cent above of pre-industrial levels. The planet left the stable Holocene period back in 1952 and entered the age of the Anthropocene with great acceleration in the last 7 decades. The summer of 2024 was a stark reality check with 22nd July being the recorded hottest day since record-keeping began in 1850.

Last year, the United Nations requested an advisory opinion from the International Court Justices (ICJ) on two questions. What are states’ obligations under international law to protect the climate systems and environment from anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions? And what are the legal consequences for states that, through acts or omissions, harm the climate and environment?

The ICJ is set to clarify the responsibilities of states to act on global warming. Fifteen Judges will decide the future of our planet. This year, the Hague hosted international organizations and more than 100 countries, including major fossil fuel users such as the United States, United Kingdom, Russia, China, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Australia, Norway, Kuwait, etc. ICJ judgements and advisory opinions are not binding under international law but hold significance in political and diplomatic arenas like the Conference of Parties. Humanity should not dominate the planetary earth system but function as a trustee of the environment and carry the responsibility by making peace with nature for inter-generational sustainability.

Indus Basin Trubulence

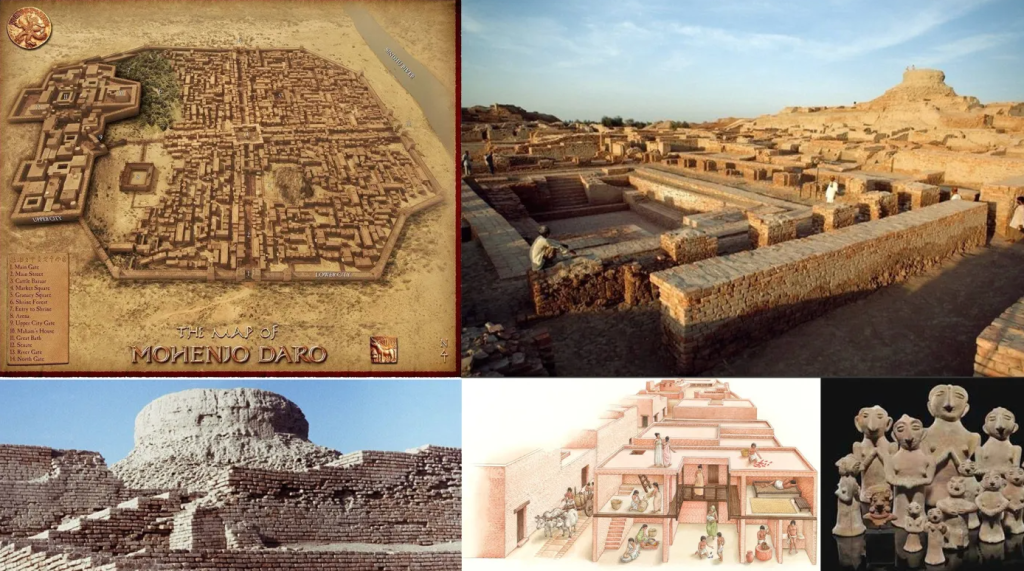

Historically, the Indus Basin’s beloved summer monsoon season and its four weather cycles were well-organized and predictable. This was due to the well-defined microclimatic conditions in this region, which hosts some of the most fertile agricultural land in the world. The area was home to the Gandhara and Indus Valley civilizations, among other ancient settlements that once thrived here. Fast forward to recent times, particularly after 1990, now the monsoon season is no longer a blessing.

As the Indus Basin grapples with scorching heatwaves, worsening water scarcity, and unpredictability, catastrophic floods, the climate breakdown we once feared was no longer a distant threat, it is happening now. Floods pose a constant threat in the Indus Basin, with 21 major events occurring between 1950- 2010, resulting in 8,887 fatalities and the nadir flood of 2022 caused over 1,700 deaths.

Over the past decade, the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) within the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) region has consistently shown signs of vulnerability and is now considered a regional tipping point. To put it into perspective, even if carbon emissions were rapidly reduced, one-third of the ice would still be lost by 2100. Moreover, if emissions continue at the current rate, the HKH region could warm up by 5–6°C, significantly higher than the global average of 2.5–3°C by 2100.

In this scenario, two-thirds of the ice mass would be lost, with changes that are permanent and irreversible. Some of the highest temperatures in the world were recorded in Sindh in Jacobabad and Dadu, around 51°C. These temperatures are classified as too high for biota to withstand. In 2023, according to an EMDAT report, Asia remained the epicenter of disaster occurrence, facing 163 disasters while navigating a plethora of social, political and economic crises.

Since February 2024, flooding affected various regions across the country, with flash floods in Balochistan killing more than two hundred souls. This year, heatwaves caused more than five hundred deaths only in Karachi, alongside a widespread hailing phenomenon leading to agricultural destruction in Punjab.

Cultural and Non-Economic Losses

Climate change poses a substantial threat to culturally rich heritage. In Pakistan, the “Shahi Qilla Chitral,” was built in the 14th century, which symbolizes the “Katoor” dynasty’s power and identity. Its architecture is a unique blend of indigenous craftsmanship and historical narrative.

Due to rapid cryosphere warming in water towers, 33 Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) sites are active as a result of decreasing albedo, leading to the increasing risk of structural degradation of this culturally significant site. Similarly, the “Shoghore Fort”, which played a crucial role in controlling historical trade routes is at the risk of high river discharges because of the additional 3044 glacial melt lakes. The damages are non-economic, that is, they pose disruptions to cultural storytelling, language heritage and cultural identity.

There are also holy sites which belong to multiple minority groups like Sikhism, Hinduism, and Buddhism that are also vulnerable to climate extremes in Punjab, Sindh, KP, GB, and Balochistan, but they largely remain undocumented to this date.

It is imperative and urgent to develop effective resilience and comprehensive climate services which can protect the rich history of Pakistan from the upcoming chaos. The climate breakdown we face today is the result of historical and ongoing actions of industrialized nations, which have reaped the benefits of rapid economic growth, powered by colonial exploitation and carbon-intensive industries and practices.

Although the window of opportunity is closing fast, the Government of Pakistan still has time to support the most vulnerable and must compensate both the people and nature that have suffered damages. We cannot afford to keep failing this wondrous planet of ours, as we did in COP29.

Cop-29: A Missed opportunity

This year also saw the underwhelming outcomes of COP29, hosted in November 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. As the president of COP29 produced a deal of $300bn for climate finance, the industrialized world is short of $1tn. The final draft has been described as a ‘travesty of justice’ because it includes private blended climate finance, which is too theoretical at this stage to achieve the target of $1.3 trillion, resonant of other overly idealized solutions like Carbon Capture and Storage Technology, Solar Radiation Management and Dehydrating a Layer of Earth’s Atmosphere.

The Climate Action Network International has described the deal as a “joke”. As Mukhtar Babayev president of the COP-29 conference stated, “I’m glad we got a deal at COP29 – but Western nations stood in the way of a much better one”.

With the global policy map fully developed, COP must shift away from negotiations to the delivery of concrete action.

Improved mechanisms to hold countries accountable for their climate targets and commitments are needed to turn the Paris Accord into delivery mode.

Need for Collective Action

The Government of Pakistan has made a declaration of a state of emergency with the recent issue of smog in Punjab, while climate lockdowns are becoming common in Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Gilgit-Baltistan too. Developing and implementing a National Framework for Climate Services (NFCS) is essential.

Pakistan’s intelligentsia must explore inclusive craftmanship to deal with such issues pragmatically and contribute legislative frameworks like 26th Amendment Article 9-A, which are more resilient and culturally sensitive about heritage. Policymakers need to be informed through discussions, workshops and co-development of action plans that can help solution implementation at the soil levels. Our focus should be on building community capacity and developing practical green approaches to safeguard cultural heritage. These efforts can lead to climate-informed investments that address the erosion of non-economic losses and damages.

Global warming poses a significant threat to the culturally rich heritage of South Asian communities. This threat goes beyond visible loss and damage; it also impacts local traditional practices and indigenous knowledge.

Effectively, tackling slow-onset non-economic heritage loss and damage demands the development of pragmatic, co-creative methodologies that can reliably measure compound events and track impacts of concurrent hydromel anomalies. Preserving cultural heritage calls for an engaged, on-the-ground approach with the communities who were directly impacted by the non-economic loss and damage of natural disasters like fire weather conditions.

Recognizing the inherently widespread nature of this challenge, regional collaboration becomes a cornerstone in addressing the interconnected cultural heritage. It is time to break the cycle of harm and impunity; humanity must divert away from man-made destruction which is causing climate change.