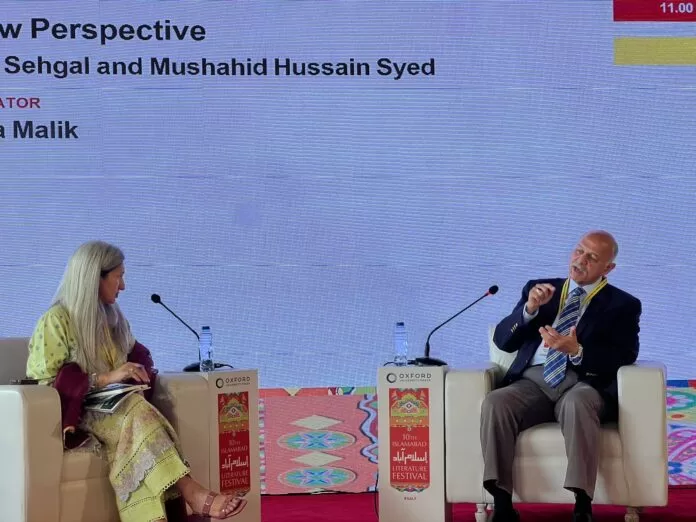

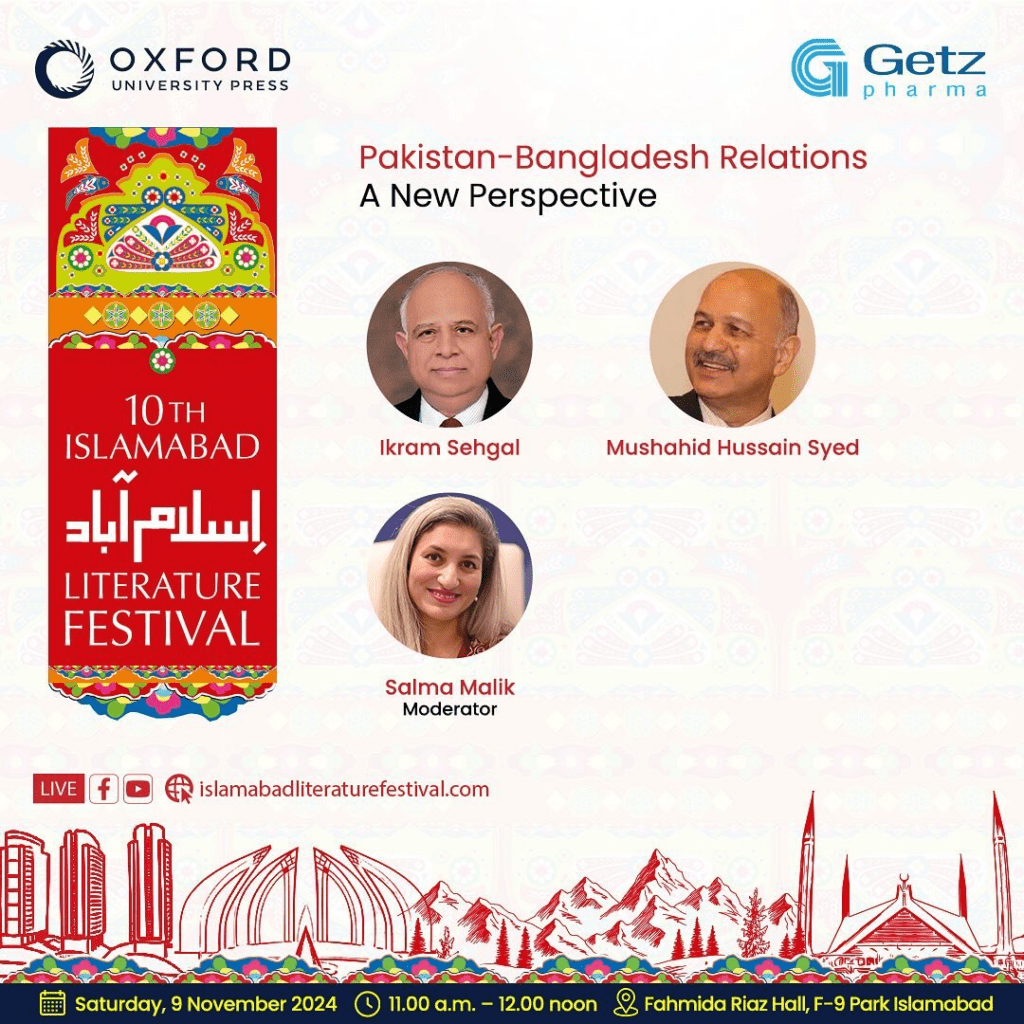

Dr Salma Malik Moderator, ILF 2024

Assalam-o-Alaikum, everyone. I welcome you all to a wonderful session that is the need of the hour. We have eminent and extremely relevant speakers who will talk about Pakistan-Bangladesh relations. We would love to gather their ideas and experiences on this, I don’t want to waste much time because this topic needs deep introspection. I am honoured to invite Mr Ikram Sehgal and Senator Mushahid Hussain Syed to the podium to start the conversation. Luckily, neither speaker needs an introduction so I won’t waste much time on that. We all know Senator Mushaid Hussain Syed. His deep work and his past as a journalist enabled him to know everything, and it’s always a treat to listen to him.

My second speaker, Ikram Sehgal, has a personal history of Bangladesh; he has Bangladesh as a part of his DNA. His roots are in Bangladesh, and he is the epitome of what Pakistan and Bangladesh could all be about had things been on a different cadre, interestingly when people of my generation think of Bangladesh, we recall several poetic memorialization. One, of course, is the fact that we have Shehnaz Begum, we have Runa Laila, Firdausi Begum, and Gulshan Ara Syed Sahiba. They are some famous singers who did a lot of work after 1971, which reminds us of that poignant moment when Pakistan lost its very important part, as Naseer Turabi said, “Wo Humsafar tha magar us sey hamnawai na thi” and Faiz Ahmad Faiz sahib talked about “Hum kay thehray ajnabi itni mulaqatoon kay baad.” What happened? Why did Shehnaz Begum’s Sohni Dharti, the icon and the symbol of Pakistan not remain Sohni Dharti much longer? Also, the fact that Shehnaz Begum as a gesture to ‘Cyclone Bhola’ talked about “Mauj Barhay ya Andhi aye Dia Jalaye Rakhna.” What happened to that “Dia”, and why did it not remain lit? I would like to ask both my speakers one after the other as they have their roots in Bangladesh.

Sir, you have the next five minutes. We have a lot of young people here, this is a generation that has very little information on 1971 and pre1971 developments. Mushahid Hussain Syed, I would start with you. I just learned that you spent a fascinating part of your childhood in Bangladesh. Kindly enlighten us as to what it was and how it could have been. Thank you.

Senator Mushahid Hussain Syed Guest Speaker, ILF 2024

Thank you very much! It’s also a pleasure to be here with such august company my good friend Ikram and the distinguished audience. My father was posted in Dhaka in the 60s; I was a young teenager studying in Adamjee Cantonment Public School in Kurmitola, which is the cantonment where we stayed in a place called 55 Tiger Road. As a journalist, I later interviewed President General Hussain Muhammad Irshad, and he said he lived in the same house because he was the Adjutant General of the Army. It was 55 Tiger Road next to the Army Headquarters. In those days, it was compulsory for students from West Pakistan to learn Bengali, and students from East Pakistan (Bengalis) would learn Urdu, like “Kema māsām ḍo bhālō āpanā bāri kōthāẏa āpanā nām ki hy.”

I think the biggest discovery was the level of political consciousness among the students of the generation. We were in Adamjee School which was an Army school and the next school was Shaheen Public School which was the Air Force School. Sheikh Mujibur Rehman’s two sons, Sheikh Jamal and Sheikh Kamal, who were older than me, were studying there, and we used to play football matches together; this made me get to know them and then I discovered one of the greatest and peasant leaders of the 20th century in Asia, his name was Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani. He was a great leader and I still remember when he came to Lahore for the ‘Kissan Conference.’ I was studying at FC College in my First Year. I, along with a small group, went to welcome him since I knew Bengali. He was there in his dhoti and having a paan, Masih-ur-Rehman was behind him and everyone was a bit silent. Mian Arif Iftikhar was there as well; he was the President of the party. As a young activist, I chanted the following slogans.

“Āmāra nētā tumāra nētā Bhāsānī Bhāsānī” “Āmāra nāma tōmāra nāma bhē’iṭanāma” “Āmāra bāṛi tōmāra bāṛi naksālabāṛi naksālabāṛi”

It was the movement of the Left, and then we said, “Saṅga ryāma saṅga ryāma cāla bi cāla bi,” which means ‘struggle will go on’. The whole place was electrified, and this gave life to the whole event. The very next day, we went with him to the Kissan Conference, where he was sitting cross-legged with his slippers on. He was the architect of getting Sylhet to Pakistan, the President of the Assam Muslim League, working with Quaid-e-Azam. Recently, I organized a conference on ‘China at 75,’ and I invited friends from Bangladesh, Maldives, and Nepal; Kalida Zia’s representative attended from Bangladesh. I have a special relationship with Bangladesh; I’ve been going there back and forth, writing for their newspapers such as ‘Holiday Akhbar’ and ‘Dhaka Courier,’ etc. I also have a good friendship with people from both parties. It still pains me what happened in 1971 because of our flaws and mistakes made us lose our brothers, but I think we have regained them now.

Dr Salma Malik – Moderator, ILF 2024

Sir Ikram Sehgal, you should be accorded a doctorate if you haven’t earned it already. We know your mother came from Bangladesh, and your father was from Punjab, Pakistan. In 1971, that connection became very problematic because there was a troubled history between the two sides, which led to the most unfortunate tragedy that befell the country. Sir, I would like to have your take on this fascinating piece of history, which Mushahid Syed has talked about, but a younger generation still needs to learn. I’m going to ask a question about this aspect later as well. What are your thoughts on why and how this all happened?

Ikram Sehgal Guest Speaker, ILF 2024 Co-Chairman, Pathfinder Group

I think, like Mushahid, I’d like to go back and give a little background of our history. You’re right, my mother was from East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, and she was very much related to the political families of Bangladesh; Suhrawardy was my mother’s maternal uncle, and Mohammad Ali Bogra was my granduncle from my mother’s paternal side. I just want to give you a perspective of how deep that knowledge is. My only sister Shahnaz, who was married to Sheikh Mujib’s cousin, is buried in Banani Graveyard, Dhaka.

So, I want to give a background that I have a lot of. We can say it’s in my DNA a bit, therefore, I approach the Pakistan-Bangladesh relation with much caution. I think this was the mistake we made in 1971 and the period leading up to it. At times, we would completely acknowledge the disparity and say, ‘Okay, fine, there’s a disparity.’ Then they tried to address this disparity and went overboard, which annoyed the establishment here. So, I think, I have learnt when I was in East Pakistan in Comilla and after my education in senior school, I went to Lawrence College and stayed there for six years (I see a lot of Lawrence College boys here). That also gave me a different dimension, a complete dimension as a Bengali, I grew up on the primary side. The senior side was Punjabi and it did prepare me to an extent for what was to come, but even then, I was not ready for 1971. You know, after 71, it’s been a roller coaster ride as far as the relationship is concerned. Mushahid and I have seen the best of the relationship after 71 and the worst of it now in the last few years, so I think that is the background.

I studied at Notre Dame College, Dhaka and I was Dhaka University’s cricket and athletics captain. Even though I didn’t attend one single day of study there, they used to give me a proxy to make me qualify as a sportsman. So yes! I know Bangladesh.

Dr Salma Malik:

The “Monsoon Revolution” and the “August Revolution” were moments of reckoning, moments of change and transition, and Mohammad Younas—one couldn’t have a better person in the office to bring about all the change. However, when undergoing such swift and rapid change after such a long authoritarian regime even the best of the best moments are difficult to capture and capitalize on. There are two things I want to ask, what do you think is the way forward? And what are those two or three takeaways from Bangladesh now?

Initially, there was this emotional flurry that we could do this, and since Sheikh Hasina Sahiba is out of the picture and now it’s all going to be a honeymoon ride, that is not the realistic take on these things. However, what are those realistic takes that Pakistan needs to do to mend the old wounds and get over the trauma memorization, which is much present on Bangladesh’s side?

Mr Sehgal, I would like to ask you what steps should be taken to overcome that trauma and develop lasting and sustainable peace. Mr Mushahid Hussain, on the political, commercial, and economic front, what does Pakistan have to offer, and what can we do? Thank you.

Mushahid Hussain:

First of all, you mentioned why they call it the Second Liberation. It’s very important to remember that the First Liberation was in 1971. Yes! They, who were leading in the creation of Pakistan, felt they were second-class citizens, and they called it Liberation, and you talk about the wounds also. The second liberation was from Indian hegemony and the becoming of an Indian vassal state under Hasina Wajid. So, what is the significance of this? I would say threefold and I think that on the Bangladesh side, there has now been a closure to 1971, which is a very significant historical change.

Secondly, there is a reassertion and I’ve been meeting Bangladesh friends, talking to them and reading their literature. The reassertion of the identity of a Muslim Bengal, they don’t talk about 1971 now, they talk of 1947 when they achieved freedom as Pakistan and that’s why the Quaid-e-Azam’s birthday and death anniversary were also celebrated there.

The third element is especially their youth, intellectuals who look forward to a very close camaraderie brotherhood with Pakistan. In that regard, our foreign policy has not been focused on this region, and we are still looking at either Washington, Riyadh, or Beijing for economic and other strategic reasons. But our strategic place in this region of South Asia belongs to Bangladesh, Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Nepal; they all would like to have a strong and close relationship with Pakistan and look up to Pakistan.

So, I would say, first of all we have strict visa restrictions for Bangladesh, that should be removed immediately. Bangladesh has done that, but in Pakistan, we still have a more ‘bunker’ mentality than the whole world. We don’t allow the Afghan trade to be closed off the Iran border, which is the problem, and of course, India, for the Indian reasons is there, and now with the killing of the Chinese, there is also this issue.

So, with the neighbourhood, I think we also had this bunker mentality that we don’t allow visitors that in fact should be opened up.

Dr Salma Malik:

I’ve seen that many countries say that we miss Pakistan in the picture, because of these restrictions.

Mushahid Hussain:

Yes! Because there is no direct flight, we need immediate restoration of Bangladesh Biman or PIA flights Dhaka-Islamabad and Dhaka-Karachi. Three million Bengalis live in Karachi and 2 million in Rohingya. Let’s start with a low-hanging fruit first and then open up. Also, we have recently provided a lot of scholarships and have done the right thing. We have given 200 scholarships to the Palestinians in Gaza, and we have done it to the Afghans; also, for the Bangladeshi students we should open up universities and special scholarship programs because it is people-to-people relations.

Dr Salma Malik: I think people-to-people contact is the one major thing.

Mushahid Hussain: This is the key, as Ikram rightly said this is a very special relationship, of popular level and I think and feel that the 1971 closure is a turning point in our history.

Dr Salma Malik: It’s so true, and especially on a day like today, the 9th of November, Allama Iqbal Day, I think this is we need to take as a major takeaway: In Bangladesh, disclosure is very, very important and Pakistan needs to realize how important it is for Pakistan to capitalize on these fleeting moments, to be very honest.

Mushahid Hussain:

The Second Liberation should also be the liberation of the mindset stuck in the past.

Dr Salma Malik: Sehgal Sahab, how important is trauma memorialization? How do you go about healing it, and what is our need? I mean, Mushahid Sahib mentioned the reassertion of identity, and there’s also this aspect about “Pakistan and Bangladesh being Blood Brothers”, Professor Shahid’s documentary we discussed before this session. So, how do you put in the lasting seeds of peace?

Ikram Sehgal: First of all, one must realize that the Bengalis are natural rebels. They were rebels in 1757, also in 1857 and rebels in 1971. I think the biggest favour that was ever done to Pakistan, and when somebody asked me what India started in 2020, they started these 50 years since 1971, focusing on genocide, etc. I said they’re doing you the greatest favour, so let them do it, because whatever they say to the young people who hate India, they will take it on the opposite side that this is propaganda and this is what exactly happened, the Indians overkilled on genocide and self-celebrations and Modi landing up by the way, when he landed he couldn’t go there by road, he had to go by helicopter because he didn’t like it. So, you have to understand the psyche of the people. Mushahid has talked about sensible things, such as direct flights. About 30, 40 years ago, I repeated what Zia-ur-Rehman had said during the first state visit to General Zia-ul-Haq in 1977-78. He said, “Sir, let’s finish all visas and all tariffs.” No visas, no tariffs, that became the base for SAARC, but today it just takes a stroke of a pen to remove all visas and tariffs. Also, make the Bangladesh Taka compatible with the Pakistani Rupee.

If somebody comes from Bangladesh and wants to buy something in Bangladeshi currency, let him pay for it at the exchange rate, and the merchants can go to the bank and change the currency, etc. Similarly, today we talk a lot about Bangladesh’s garment factories and there is no doubt about it, but who is behind the textiles? They are Pakistanis with third-country passports. They said, “Don’t have a Pakistani passport; bring your British passport or a Canadian passport or any other passport.”

We have an absolute base of an industry already going there and again, there is no such thing as a lot of people talking about hatred among the young youth. All right! Why did they stop hoisting flags in the cricket stadium during Pakistan matches? The stadium used to be full of Pakistani flags. They were not Pakistanis, but why were they carrying Pakistani flags? So, how they reacted was they made it a general rule and said there would be no flags in any matches.

Dr Salma Malik:

Sehgal Sahib, I would also like to ask you one thing. One of my colleagues pressed me that this topic should be taken up, and that is the Bihari question. Can we now revisit that question? Can we do something about it? This is the group that has put the Pakistani flag on their beds, and they call themselves Pakistanis even among all the adversaries. What does it mean?

Ikram Sehgal:

First of all, they have a right to Pakistan. They opted for Pakistan so there is no doubt about it. You have three million Afghan refugees here, one and a half million registered and a half million unregistered. You have Afghan refugees now here as Pakistani nationals. Even in Islamabad a lot of houses are full of Afghan people. How can you deny the people who had a right and who fought for Pakistan at that time? You cannot deny them this right, so you have to restart. It’s even started; there is a fund that is still growing, by the way Saudi Arabia placed 100 million dollars, and all those people brought them by air. Then, it was stopped because they should have shared it equally among the provinces; they should not have sent them all to Karachi which aroused resentment among the Sindhis. It is very right because nobody wants to become a concentration there.

But the point is, first of all, we must solve considering it a Pakistani problem. It’s not a Bangladeshi but a Pakistani problem. It is their right and they must take this right. Secondly, that is what you have to do; even the Bangladeshi told them that people who want to take the Bangladeshi nationality, do take the nationality. Do you realize that the hardcore 300,000 were in Dhaka, most living in Mohammadpur and Mirpur? They still call themselves Pakistanis. I think you must take a very positive and passionate view of it, not a dispassionate one, and must give them their right. I think it can be solved.

I want to add one thing that people do not know about 1971: the total amount of Pakistan Army troops that were deployed in East Pakistan were composed of three and a half lightly armed divisions who did not have their full complement of Artillery, they didn’t have their Armour, most of them were only carrying light weapons. Now, why does Bangladesh need 10 Infantry divisions with 9/10th of the border with India?

There are 10 Infantry Divisions and a number of armoured brigades that compose one Armored Division. Why does Bangladesh need that? Whatever it is, and even then, like Mushahid was saying, the Indians had intentions of protecting things by stationing one division as in India, and it would have never happened in the sense that they wouldn’t have agreed to it. Still, my point is that there is enough goodwill as I speak today.

Yesterday or the day before yesterday, one of the senior army officers of the Bangladesh Army, and I will not take his name, his wife had a kidney transplant in Lahore; she is still in the ICU right now, but I was trying to call him before you came, I was trying to put him on the telephone for you to understand that this is the type of links we keep across the board.

I used to lecture at the National Defence College of Bangladesh for many years until 2013 when the Indians decided I was persona non grata. Still, you know you must be practical and pragmatic, and you must understand that the Bangladeshi youth now is diverse from 1971.

It’s a distant history in the same manner that Europe and the holocaust have become a distant memory; even though Israel keeps bringing it up, it is not that most Jews discuss it. Jews were taken from Ukraine in the concentration camps not so much in Germany. People think Germany has the largest number of Jews, but Poland, Ukraine, and France have the largest Jewish populations. So, I think 50 years is a long time to forget the past and look forward.

Dr Salma Malik:

Insha Allah, before I open the floor for questions and comments, we have a sizable number of youth sitting here. What I saw when I got a chance to visit Bangladesh for the first time was on 16th December, and we had a PIA flight. I was in Dhaka and you people know how important 16th December is, when I opened the curtains of my hotel room there were pictures of 1971 in front which disturbed me.

I started thinking weird thoughts and when I reached the airport with all the VIP protocols, it was a young couple standing with their kids there; they were travelling to America and in the good old days of PIA, so Pakistan was the transit.

The man came to me and his family was in a state of great distress. He said, “My wife and daughters have to transit through Pakistan, so are they safe?” I was very hurt. At first, being a young person, I said it was safe, but later, I realized they were also going through what I had gone through. So I sat with her and I took another day’s flight to Islamabad, and I helped them out.

Can we cover up this trust deficit? There is a young generation in Pakistan who are unaware of 1971 since they are least interested in Molana Bhashani, Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy, and Mohammad Ali Bogra, the rebellious nature of the Bengalis who got us 1947, who got us Pakistan. In Bangladesh, there is a divided youth: the one who followed Hasina Sahiba and the one who we see today prominently holding up the flags of Pakistan. How can we unite these two generations across the divide and what do we have to tell them?

Mushahid Hussain:

Some areas are above politics and one of them is sports. The cricket test is the classic. My younger sister was in Bangladesh, Head of the World Bank, and she was there for the cricket match between Pakistan and India in Dhaka; she said I felt that I was in Lahore, and there were chants of Pakistan Zindabad, and flags were banned afterwards. Hasina walked out of the match because we were winning, so what I say is popular. They were mostly youth, and that’s why I feel that this engagement, and I agree with Ikram about those tariffs, visas, and unnecessary police reporting.

Bangladesh is not an enemy country; the old mental barrier has to be broken, and I think this engagement will bring Bangladesh youth there, let’s bring the youth there. I got my political consciousness in Dhaka, former East Pakistan; the people are lively with dynamism and vigour, and, as you said, the culture of defiance and resistance.

This student revolution came in January 2024 when people had started saying that Hasina Wajid has now come to stay forever. They swept the third term and formed a one-party state; everyone accepted it. Some people in Pakistan have even started saying that the Bangladesh model is very fine i.e. give a baton and keep doing the economic development. Nothing will happen.

But it fell apart in a jiffy. It just unraveled and the first statement made by Jai Shankar after that on 7th August was raising the issue of minorities in Bangladesh, and they exploited it a lot. In the second statement, he said, “The merger of East Pakistan and Pakistan has damaged our minorities a lot,” and that happened in Bangladesh.

You see that as an impediment to the development of your own country, and this is the seen as change now people even refer to history as Ikram said Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy in 1946 has proposed to the Quaide-Azam and Mountbatten that there should be an independent Bengal, a Muslim Bengal, the Assam and Bengal, Quaid-e-Azam accepted it and even Mountbatten accepted it. Still, Congress led by Gandhi and Nehru, shot it down. The history of 1947 restored the Muslim Bengal identity, which was reasserted in this revolution.

Ikram Sehgal:

I would like to start with the Quaid; he was one of the greatest strategic thinkers of his time; the first strategic decision he took was on 25th May, 1942 when, on 8th May 1942, Gandhi and Nehru and the Indian National Congress “Quit India” to the British, the Japanese had taken Singapore, the Germans were knocking at the doorstep of Cairo, and he took a decision and said ‘No’. The Indian National Congress also said no, the Indians should join the British Army. He said, “No, you must fight for the British.” That was the strategic decision that was honoured by the British in giving us an independent Pakistan because they said the Muslims stood by us and we could not abandon them. That was a great strategy.

The second strategic decision that Mushahid talked about was when Quaid-e-Azam went to Master Tara Singh, and they talked about Sikhistan. He said, “If we had an independent Sikhistan, there would have been no Kashmir problem, and there would have been no water problem.” Mountbatten had this plan. It was the pressure of the Indian National Congress that they changed it, and they had this vote we have to do strategic thinking. India keeps doing whatever it feels like. What is stopping us from asking for an Association of Indian Northeastern States, such as United Bengal and Assam, with Bangladesh as its core confederacy? What is stopping us from supporting the Khalistan Movement openly? They support the fact and they keep on talking; Amit Shah talks about Balochistan all the time and other places. So, what stops us from talking about the Khalistan Movement? The Khalistan Movement is recognized in Canada the United States, and all over the world.

Dr Salma Malik:

Sehgal Sahib, unfortunately, you would agree that we have missed many grassroots movements, even in Kashmir. If we had capitalised on them, this narrative would be quite different. If we keep talking about Bangladesh, I think it could take a whole day since. it’s such an important topic. I have already moved past the 30 minutes that I said would be given to the speakers; we have the next 20 minutes, and I would invite questions and comments from the audience.

Question: Assalam-o-Alaikum! My name is Ali Rizvi and I am a journalist. My question is for Sehgal Sahab but before I ask the question, I would like to begin with an anecdote about the 16th of December 1971. I lived in Kuwait as a 10-year-old child with my family. I used to write letters to my grandmother from Kuwait.

The best part of those letters was when I used to write the address on the envelope because that gave me a chance to express my nationalism when I wrote the address of my country. So when I wrote the letter in 1972 and I wrote West Pakistan, my father said no, you don’t need to write West Pakistan. It’s just Pakistan now.

I’ve been listening to this Bihari question for the last four decades. I haven’t seen anything concrete, and since you said we should be practical and pragmatic, unfortunately, I haven’t seen the solution to this question in my lifetime. Don’t you think it’s high time the United Nations intervened in this matter? If not, are we not willing to sort this matter out? Does the UN do something to get those people settled in some third country? Thank you very much.

Ikram Sehgal:

Sir, do not expect anything from the United Nations. If they can’t do anything in Gaza, what can they do about a thing that happened 50 years ago? Let me put it like this: I was Director of Bank Alfalah for 16 years, and Sheikh Nahayan asked me to look after Bangladesh, and I opened up branches there. I opened one branch in Mirpur and when I went there for the opening ceremony, I spent an hour there and as I walked out. I saw a silent crowd, jam-packed all over the streets, quietly standing there, not saying a word.

They were all stranded Pakistanis, and I’m talking about something 30-35 years later. So, whatever we have to do, it is to be done between us and Bangladesh, and it can be done because the funds are there they have gone nowhere, in fact, they must have built up by now and must be in the billions so we can do that it has to be a bilateral thing. Do not expect anything from the United Nations.

Question:

My name is Sajid Khan and I am from Waziristan; my questions are for both speakers. Sir, my great-grandfather fought in the battle of Kashmir, and his younger brothers and cousins fought in the battle of Bangladesh. It feels very good when we read Ikram Sehgal’s book, Escape from Oblivion. It is in itself a nightmare. You talked about a nightmare in the book, but there is an element that is missing: the female element. This is an element which nobody talks about.

When my great grandfather went to Kashmir and fought they used to pull earrings from the ears of those females since they talked in Urdu, they could be Non-Muslims. Then the others who were coming back from Bengal brought women with them as maal e ghaneemat. Now, those women are living in Waziristan as head of a family. Some of them are now the grandmothers but they are not mentioned anywhere in the history. They should be reunited with their families, if alive but most of them are dead and their graves are also in Waziristan. Sir, what would you like to say about it?

Dr Salma Malik:

This is a very important and valid question since whenever we consider conflict as a matter of narrative, women are not factored anywhere, and it’s a human tragedy. Sir, if you spare a little thought on this, Ahmed Sahab, ask your question, and then we will answer both questions together.

Question:

Mushahid Sahib has just spoken about the resurgence of Muslim identity in Bangladesh. We have been watching the developments very closely. So, I want to know, what are the prospects of Bangladesh’s resurgence of Muslim identity going the way of creating an Islamic Republic or they may learn a lesson from us and not do that.

Mushahid Hussain:

I think the Muslim identity they talk about is the vision of the founding fathers of Pakistan, which is not theocratic, which is not learned by clerics, which is not the model based on any theocratic state. It is the identity in the cultural sense, a distinctive identity that shows that they have a heritage inspired by Islam. I don’t think it’s leading to the Islamic Republic, but I think it certainly does undermine the so-called secularism of Hasina Wajid Sahiba, which they equate with Indian domination.

So the Muslim assertion is the natural assertion of an identity that led to the struggle of Pakistan in 1947 and which somehow was then covered up with a very strong animist towards Pakistan and a very strong proclivity to promote Indian interests at the expense of Bangladeshi Muslim nationalism.

So, I would say it’s not theocratic, it’s not mullah driven, and it’s not clerical. It’s a natural assertion and one of the natural assertions of the Muslim identity is the restoration of their brotherhood or camaraderie with Pakistan moving forward, so I think it’s a positive assertion, not a negative one.

I would also like to recommend to you since you mentioned ‘Blood Brothers.’ There is a very good podcast coming from Bangladesh by a young Bangladeshi living in the UK, Dilly Hussain, and his recent podcast, you should see, is with Professor Shahid-u-Zaman the former Chairman of the Department of International Relations of Dhaka University. I think examining in detail from a new mainstream Bangladeshi perspective the post-revolution Bangladesh emerging with a stronger Muslim identity is very instructive.

Ikram Sehgal:

I think you know women’s empowerment, and it’s correct that you must give women the right place. Bangladesh has done it much earlier than us and if you look at it, one of the reasons for Bangladesh’s economy being what it is, is because of the empowerment they’ve given to women and Gramin Bank, of course, and then the other things which have come up after that they’ve added to it.

So, one must recognise the sacrifices they’ve made, the sufferings they’ve done, etc but I want to go back to that Islamic Republic question. If they become an Islamic republic or remain secular that is their business; we have nothing to do with that.

Our relations should be confined to bilateral, what they have in their foreign policy, what they have in their trade policy, and what they have in their defences is their business. Our business should be what concerns the relationship between us, especially trade. Does our relationship with China suffer because China is not the Islamic Republic of China? We have to be very clear about it, that it does not matter what that state is. That is their business, and we should have nothing to do with their Internal or External Affairs. The only thing we should be concerned with is our bilateral affairs. Thank you.

Dr Salma Malik:

Please take questions from all and then we will ask our speakers to respond together due to shortage of time.

Question:

Hi, I’m Sheeraz, a graduate of security studies. We have seen chanting of the famous “Tum bi (rajakar)Razakar and Hum bi Razakar” in Bangladesh so that we can understand the sentiments of the youth, but one thing is missing; how do you explain this thing that their bureaucracy and establishment have spent decades in the specific mindset. So, what barriers can influence the new bilateral relationships between Pakistan and Bangladesh in terms of their bureaucracy and establishment?

Question:

It’s just a pleasure listening to both of you. I was a little confused since Bengal is of Tagore and Amartya Sen. It is fascinating that the Muslim League is being formed there, the Swadeshi Movement is also there, and Mukti Bahini is also there. There is East Pakistan and then Mukti Bahini, so I cannot understand this conflict. Now, we are beautifully talking about visa-free tariff-free Bangladesh and that conflict that remained a part of our history. How would you look at that?

Question:

Assalam-o-Alaikum, Sir, I’m Abdullah Ghazi from Lawrence College, and my question is for Mr Ikram Sehgal. Sir, we have seen Hasina Wajid’s government has been overthrown in Bangladesh, and during her rule, Pakistan didn’t have good relationship with Bangladesh. Do you think is it possible for the new governments to make good relationships with each other? If so, how will they make it sustainable?

Mushahid Hussain:

The biggest impediment is the traditional bureaucratic establishment worldview or mindset in Pakistan and Bangladesh about each other because, for a time from the brotherhood, this also goes to the lady’s question, which I’ll briefly tackle. We had started seeing each other as enemies in a way that what is India’s problem is Pakistan’s problem.

People have changed that mindset; the opinions in Islamabad or Dhaka officials may not have changed that much but the ground realities have changed in Bangladesh and Pakistan also. In Pakistan, the people are very vibrant, our state structure is dormant bureaucratic and backward as well as quite archaic but our society in which we have women, youth, media and think tanks have a life, current and full of dynamism.

So, we have to decide on the highest political level that breaks these artificial barriers of visas or tariffs, and Ikram is right. It’s very important that most of the new investments that have taken place in Bangladesh in the past decade—one decade—70 % of them have come from Pakistanis who are investing in Bangladesh under different passports and so forth, so the base is there, and the goodwill you find in Dhaka or Bangladesh is amazing.

So, I think we have to cut through that; about the other question, let’s see the history of the last 100 years. In 1906, the Muslim League was formed in Dhaka, and 1906 another thing took place: the partition of Bengal, which ended under the pressure of, I’m sorry to say, a Hindu community, so that is again a bleeding wound and then 1946, they talked of an independent state of Bengal which Muslim League under Quaid and which Mountbatten even agreed again was opposed and nullified by the Congress because of the religious question, because the majority would be Muslims. So I think that doesn’t go away, history doesn’t go away. I’m reminded of two quotes, and I’ll end with that on 17th of December 1971, after the partition of Pakistan, Mrs Indra Gandhi addressing the Congress Parliamentary Party, said “We have taken the revenge of 1000 years.”

I asked my friend, who was a professor at Delhi University that we were only a 24 year old country, what was this revenge of 1000 years? He said the 1000 years she was talking about related to Muhammad Bin Qasim.

Secondly, in the Crusades, when the Ottoman Empire collapsed and General Gouraud from France went to Damascus in 1917, he first went to the grave of Salahuddin Ayubi. He said, “Oh Salahudin! We have taken revenge after 700 years,” that revenge was for the Crusades, so the history doesn’t go away.

As Ikram said, the revenge of the Holocaust is being taken from Gaza; I mean, the Holocaust was a crime against humanity committed by the Christians of Europe against the Jews of Europe, and the people of Palestine are suffering for that. Thank you.

Ikram Sehgal: I left a last bit of information about 1st March 1971. People don’t know that I was the helicopter pilot of the Commander of Eastern Command, Lt. Gen Sahibzada Yaqoob, and we flew out to Comilla in the morning. While flying, I asked his permission to go over to the Dhaka Stadium because a match was being against Pakistan’s cricket team. So, we flew over Dhaka Stadium, and the flags were flying, the people were cheering, etc.

We went to Comilla and two or three hours later while coming back from Comilla, I took a circuitous route and approached from East Dhaka because there used to be a lot of birds and eagles over Dhaka city.

As I landed, Brig Jahanzaib Arbab and Major (Later, Brigadier) Jaffer Khan were standing there with the Brigade Commander of 57 Brigade and said, “Have you enough fuel?” because we wanted to do about a 30-minute ride. I said, “Yes, let’s do the thing,” so I took off again, and we saw the whole road was on fire, with roadblocks everywhere. Dhaka Stadium was on fire. This was just in four hours.

I asked, “Sir, what happened?” I was wearing a helmet so as I was not very aware of everything, I was more worried about the fuel, and he said, “Well, the President has postponed the National Assembly session, and this is the reaction, and we have to see Narayanganj because Adamjee Jute mills are on fire.”

So, of course, we went there while coming back again, this time I went straight, and there were people on rooftops.”

At that point, it was decided to take refuge. People from the Dhaka Cricket Stadium, especially West Pakistanis, were being evacuated.

When we landed back, Brigadier Jaffer Khan – also from Lawrence College, by the way, for those (Lawrence College people who are sitting here) who might know him – was the Head of the Peake House. He said to me, “Ikram, go get them – the people on the rooftops.”

So, I flew out and picked up people from various rooftops with whatever fuel I had left. When I landed back, General Sahibzada Yaqoob had already come back to the helipad. Gen Sahibzada Yaqoob, Gen Khadim Hussain Raja, Brig. Jahanzaib, their faces were ashen.

You know, on that day, 1st March, we lost East Pakistan. On 16th December, the Commander of Eastern Command said, “We have lost East Pakistan.” You can’t go back and rewrite history so don’t think about it.

Think about the fact that today, in Pakistan, we are surrounded by 8 billion people in the world, 5 billion people are around us. What Mushaid has done with the first think tank on Africa, PAIDAR is tremendous.

Pakistan has the second-largest gold reserve in the world, the third-largest cotton industry in the world, the fourth-largest rice-producing country in the world, and the fifth-largest milk-producing country in the world. The sixth largest wheat-producing country in the world is Pakistan.

We have developed the means for missiles and different things, and we have the greatest talents in the world among our youth. There is no other talent that we are the bridge to everywhere.

It is for us to exploit that bridge, and Bangladesh today can be our partner. I would like to thank you since I’m from Lawrence College. I can see a lot of Gallian here, and I am what I am because of Lawrence College.

Dr Salma Malik:

With the two best ambassadors from Pakistan to Bangladesh, you both should decide who will serve as the Ambassador first, since you both spoke from your heart. I don’t have many words to summarize this beautiful and deep conversation.

Even though I am not poetic, on a topic like Bangladesh, I would like to narrate poetry, and I’ll conclude this session on Ibn-e-Insha’s very poignant poem that we mentioned in the beginning that we penned on Operation Cyclone Bhola, which is one of the very devastating factors that has divided East and West Pakistan.

“Mauj Bharay ya Andhi aye Dia Jalaye Rakhna Hai,

Ghar ki Khatir Sau Dukh Jhelay Ghar to Akhir Apna Hai”

I can only wish and pray that we both realize that this is our own home, we have a common root, our trajectories might be different but our path to progress, success and sustained relations depends on better relations with each other.

I want to thank both speakers for sharing their valuable opinions and experiences. Thank you so much to Oxford University Press, the Lawrence College students, and the audience who joined us today.