“There is nothing further here for a warrior. We drive bargains …… old men’s work. Young men make wars, and the virtues of war are the virtues of young men: courage and hope for the future. Then old men make the peace. And the vices of peace are the vices of old men: mistrust and caution. It must be so.”

-Sir Alec Guinness (Prince Faisal) to Peter O’Toole (Lawrence) in a scene from the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia

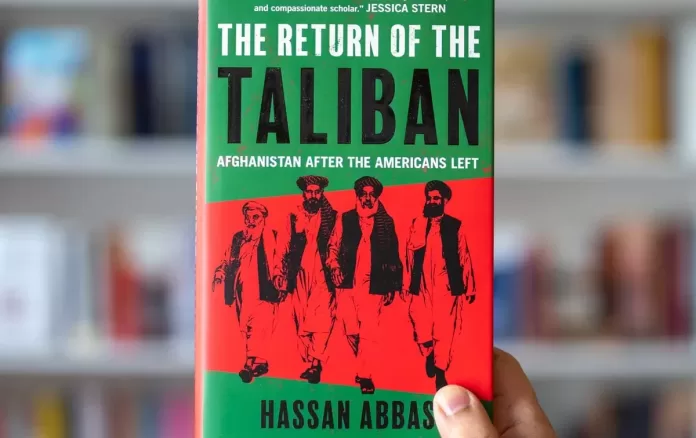

Hassan Abbas’s book “The Return of the Taliban” is the first book about the second Emirate of Taliban after their return in August 2021. Hassan’s informed account provides details of the negotiations that led to the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, structure and various elements of the new regime and internal dynamics of the new set up.

Hassan is a well-informed scholar with over two decades’ experience of the region. He has used Afghan including the Taliban, American and Pakistani sources with firsthand experience about the events described in the book.

The book consists of six chapters. The first chapter is the most important one and deals with the Taliban-US negotiations that paved the way for the return of the Taliban and this process set in motion events that foretold the collapse of the Afghan government that was built with American blood and treasure. The second chapter explains the transition of the Taliban from insurgency to governance. The third chapter examines the policies of the Taliban related to various arenas and cooperation and competition among various factions. Chapter four explores the Deobandi roots of the Taliban’s ideology and how the Taliban worldview has been rejected by almost all Muslim countries.

Chapter five explores Taliban’s contentious relations with Pakistan especially in the context of Taliban’s alliance with Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) that is attacking Pakistani security forces and the deadly conflict with Islamic State Khorasan (ISK). The last chapter deals with the Taliban’s relations with China, Russia, Iran, Turkey and bordering Central Asian states.

In the concluding chapter, Hassan, while acknowledging the medieval worldview and regressive measures of the Taliban, advocates direct engagement with the de facto government. He hopes that this engagement will help to integrate Afghanistan with the international system and ease the suffering of the common Afghan. However, in 2024 no one in Washington is interested in Afghanistan and willing to waste any time that has no career or financial prospects.

Only the intelligence community has a limited interest to keep a watchful eye on the region about potential extremist threats to American interests. This is the reason why CIA director William Burns met with former detainee of Pakistani jail and now a power broker in the Taliban regime Abdul Ghani Baradar (reported by The Washington Post) and CIA deputy director David Cohen met with former Guantanamo Bay detainee and now head of Taliban intelligence, Abdul Haq Wasiq (as reported by CNN).

This limited and behind the scenes interaction away from the limelight serves the interests of both parties.

This book is a timely and scholarly work that provides details of the events and complex dynamics that led to the return of the Taliban in 2021. Hassan Abbas’s book is highly recommended to scholars and policy makers for better understanding of the complex theatre. Those of us familiar with Afghan society and following the events of the region in the last two decades were clear about the events in Afghanistan. For centuries Afghan players on the power chessboard have used external forces for their own internal power struggles. At all levels of the US government, a large amount of data was selectively interpreted to spin the story while privately many were clear about the futility of the exercise.

Predictably, Americans were simply throwing more money and bodies at the problem and hoping that it would go away. American and Afghan players were deceiving each other for their own ends and the outcome was a forgone conclusion as attested by the history. Outsiders fearful of distant threats emanating from Afghanistan hastily thrust their hands in the snake pit of Afghanistan.

The lengthy list includes the British fearful of Russia; both Tsarist and communist threatening their Indian empire, Russia fearful of the British and then the Americans coming close to its southern borders, Americans fearful of extremists and Pakistan fearful of a hostile country on its western border, all of them have paid the price of their fears.

Many who don’t like Americans romanticize the Taliban, but the full drama is usually a mixture of history and human psychology. Afghan power brokers of all shades, including the Taliban have cashed in on the fears and ambitions of foreigners.

Shah Shuja lost his throne in 1810 but was lucky to keep his eyes and head intact and became a British pensioner in Ludhiana. He re-gained the throne in 1839 overthrowing Dost Muhammad Khan with the help of the British Indian army bayonets. Dost switched the place and now became the British pensioner in Mussoorie.

In 1842 when the British decided to quit Afghanistan, Shah Shuja was murdered by his fellow Afghans and Dost came from his exile in British India to re-gain the throne. Since then Afghan history is a recurrent cycle where those who were lucky to escape in time became exiles (Abdur Rahman Khan 1869, Sher Ali Khan died in 1879 while fleeing north to find refuge with Russians, Yaqub Khan got first pension from Persia in 1870 and second from British in 1879, Amanullah Khan 1929, Zahir Shah 1978, Babrak Karmal 1992 and Ashraf Ghani in 2021).

While those who waited too long were killed by fellow Afghans (Shah Shuja 1842, Habibullah Khan 1919, Habibullah Kalakani 1929, Nadir Khan 1933, Noor Muhammad Tarakai September 1979, Hafizullah Amin December 1979 and Mohammad Najibullah 1996).

Hassan has summarized the American project in one sentence that “it is as much about misplaced idealism as it is about self-deception funded by a dangerous amount of money.” The first chapter of the history of American intervention in Afghanistan costing one trillion dollars is written by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) but the complete history is still to be written.

“What all the wise men promised has not happened, and what all the damned fools said would happen has come to pass.” -Lord Melbourne