The concept of “security” is deeply rooted in history, deriving from the Latin word “securus,” meaning freedom from worry. It evolved in the 16th century as states became the primary actors in the international system post-Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, making security a top priority in a self-help world. This basic understanding of security has expanded to include a wide range of measures to safeguard people, resources, and interests, encompassing strategies to protect states, societies, and individuals from various threats. Historically, security was synonymous with a state’s military strength and its ability to defend against external threats. This traditional concept focused on protecting the state from external dangers through military and technical capabilities. Internally, threats like terrorism, disease, and civil unrest often stem from poor governance and economic mismanagement. The traditional view of security emphasized national security and protecting a nation from external threats through military power, economic strength, and international treaties.

In the 21st century, security now includes non-traditional concerns such as energy, technology, food, water, environmental degradation, climate change, and human health. This shift reflects a growing recognition that security threats are more wide-ranging and interconnected than previously perceived. Non-traditional security threats are now considered equally significant, emphasizing international cooperation and human security.

Prominent scholars like Barry Buzan have proposed a multi-layered security framework encompassing military, political, economic, societal, and environmental sectors. Each sector can be threatened, and a state’s overall security hinges on its ability to address these diverse threats. This broader perspective recognizes that security involves protecting both states and individuals from a wide range of challenges.

The Security Dilemma and Global Cooperation

The ‘security dilemma’ highlights the paradox of national security efforts, where a strong military may deter attacks but also be perceived as a threat by others, potentially fueling conflicts. This dilemma reflects on necessity for cooperative and combined security mechanisms. Post-Cold War, the international security landscape shifted towards combined and cooperative security mechanisms to address new challenges like weapons proliferation, terrorism, and environmental threats. Immanuel Kant introduced cooperative security, which emphasizes on international collaboration to tackle transnational threats. It evolved significantly during the Cold War, primarily within the European security complex, emphasizing multilateralism, economic development, and comprehensive security policies. In the 21st century, organizations like NATO and the EU exemplify this approach, promoting stability through dialogue, preventive diplomacy, and collective defence. Despite its challenges, cooperative security offers a promising framework for addressing modern security threats through international cooperation.

Maritime Security

Maritime security has changed significantly over centuries, shaped by power dynamics and economic interests. From the Iberian Period dominated by Portugal and Spain to the Trading Companies Era and the Sea Power Era, each period contributed to the development of modern maritime security.

In recent years, the importance of maritime security has escalated dramatically. This is due to traditional concerns like piracy and armed robbery, as well as new threats such as transnational criminal organizations using the seas for smuggling. Cyberattacks targeting maritime infrastructure and growing geopolitical tensions in key regions like the South China Sea add to the challenges. The Suez Canal and Panama Canal play crucial roles in global trade by providing efficient routes for shipping goods. However, recent disruptions and natural calamities have posed significant challenges to these routes. The container shipping industry is in trouble due to the decreasing practicality of using the Suez Canal as a primary cargo transportation route. Major freight companies, including the largest global container shipping line MSC, have bypassed the Suez Canal due to intensified attacks on commercial ships in the Red Sea by Houthi militants from Yemen. These attacks, in response to the Gaza conflict, have increased war risk insurance premiums and impacted crucial trade routes, particularly for oil. The increased war risk premiums add significant costs to shipping lines, ultimately affecting forwarders, buyers, and end consumers. The importance of naval powers has increased due to geopolitical tensions in key maritime regions, further threatening global trade and stability.

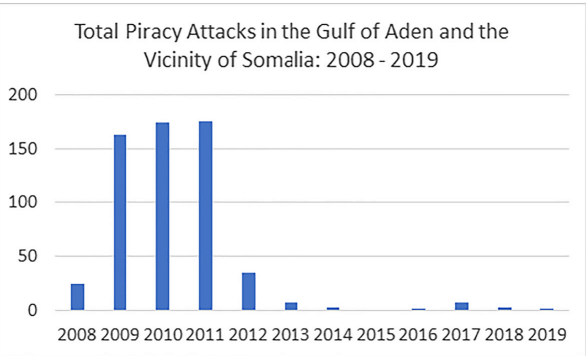

Figure 1: Total Piracy Attacks in the Gulf of Aden and the Vicinity of Somalia: 2008-2019

Naval power is crucial to ensure global security through maritime security operations, humanitarian assistance, and regional cooperation. Navies combat piracy, human trafficking, and the proliferation of weapons, ensuring the free flow of commerce and protecting national interests. International cooperation has reduced piracy in regions like the Gulf of Aden. According to the ICC International Maritime Bureau, pirate activities have increased in the Gulf of Guinea, where most attacks are away from the coast. It is required to increase coordination and information exchange in the region for the safety of seafarers.

The United Nations, European Union, and several other nations’ persistent patrolling and high-visibility security have reduced attacks from 166 in 2011 to just 1 in 2019. Piracy has surged in West Africa, particularly in the Gulf of Guinea off Nigeria. Of the 162 global piracy attacks in 2019, 64 occurred in this region. The International Maritime Bureau reported that 90% of global kidnappings at sea occurred here, with the number of kidnapped crew members increasing by 50% from 2018 to 2019.

Importance of Maritime Security for Pakistan

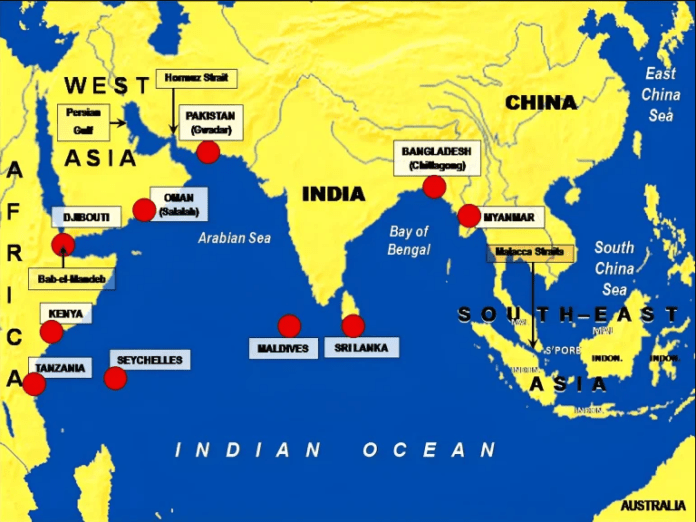

Pakistan’s maritime interests are intricately linked to its economic prosperity, regional stability, and national security. The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is significant because 65 % of the world’s oil, 35 % natural gas as well as sources of numerous other manufactured goods and raw materials are located in the littoral states of the Indian Ocean. It is also significant for global security and economy because of important trade routes and choke points. Thus, the global power dynamics depend on the region as it is rimmed by three continents; Africa, Asia, and Australia. It connects the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans – the global, economic and political powerhouses lie here.

Halford Mackinder in the early 20th century (1904), suggested that control over the heartland of Eurasia, primarily Eastern Europe, is crucial for dominating the entire world island of Eurasia and ultimately achieving global supremacy. In the mid-20th century, Nicholas Spykman proposed the Rimland Theory; controlling the coastal fringes of Eurasia, known as the Rimland, is essential for global dominance. This theory directly challenges the Heartland Theory, emphasizing the importance of maritime power and control over trade routes rather than land-based control.

Alfred Thayer Mahan’s theory also emphasizes the crucial role of maritime strength in shaping a nation’s geopolitical influence and global dominance. The Indo-Pacific region’s strategic importance is highlighted due to its extensive coastlines, vital sea lanes, and strategic chokepoints, pivotal for securing trade routes and maritime interests.

The Arabian Sea holds a central position within the Indian Ocean, serving as a crucial route for energy supplies and providing access to vital choke points such as the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz to the West, and the Bay of Bengal and Malacca Strait to the East. In addition to energy supplies, the Arabian Sea is an important route for global trade of various commodities and raw materials. It also offers the shortest sea access to landlocked Afghanistan and Central Asia. The Arabian Sea’s significance has grown significantly with the initiation of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project, which is itself a flagship project of the broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The development of the Gwadar Port and its accompanying infrastructure is a cornerstone of the CPEC, which aims to facilitate Chinese exports and energy imports through Pakistani ports, particularly the port of Gwadar. Gwadar’s strategic location, providing a shorter sea route for Chinese trade to the Middle East and Africa, makes it a crucial component of China’s global economic ambitions. It is envisioned to boost Pakistan’s economy and enhance regional connectivity.

China’s interest in Gwadar as a potential naval outpost could enable it to counter U.S. and Indian naval influence and gain control over critical maritime chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz. Establishing a permanent base at Gwadar would shift the power balance in the Indian Ocean, challenging India’s regional dominance. China is working to bolster military control in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) by securing rights at ports and establishing foreign military bases.

China has a presence in the following ports – mainly declared to be used for economic and commercial purposes: Kyaukpyu in Myanmar, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Feydhoo Finolhu in the Maldives, Gwadar in Pakistan and Obock in Djibouti. In 2017, Beijing set up its first overseas military facility in Djibouti (Africa) on the Indian Ocean coast whereas France, Japan, and the United States also have facilities in Djibouti.

Pakistan with CPEC and maritime sea route provides a unique opportunity for China to connect to the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. The railway and road network between landlocked Central Asia and Pakistan can be a game-changer for these Central Asian countries.

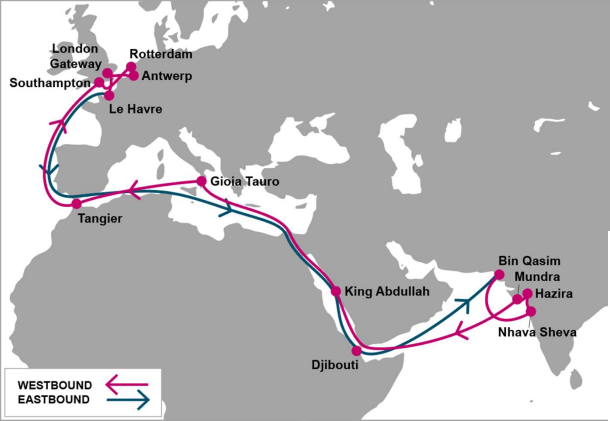

The cheapest and easiest way is the maritime route, as South Asian trade through the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is both west and eastbound: west to the economies of the Middle East, Africa, and Europe, and east to ASEAN and the economies of the Asia-Pacific.

Figure 2: Bin Qasim Port to Le Havre Port

The importance of CPEC and the ports of Pakistan has increased now as China is facing trouble in the BRI projects, which have been extended to almost 70 countries. China is relying on CPEC connecting Kashghar to Karachi and Gwadar through a road and railway network and the maritime route to Europe.

Ikram Sehgal, a renowned defence analyst suggests that as the port of Gwadar has been developed into South Asia’s largest port, this gives China direct land access to the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean avoiding the Malacca Strait chokepoint, through which the majority of China’s imports of crude oil currently travel. With the help of this corridor, China will also find it simpler to market its products to Pakistan’s expanding middle class and beyond.

India is investing fiercely in the development of Iran’s Chahbahar port to gain easy access to Central Asia through Afghanistan and direct access to the Arabian Sea, which would provide India with a strategic advantage. Additionally, India is aiming to secure its energy routes and counter the increasing Chinese presence in the region. To achieve this, India has formed an economic and strategic alliance with both Iran and Afghanistan. The development of these two ports by major regional powers may result in open rivalry and competition between the countries or lead to disputes over the economic and natural resources of Central Asia.

India and Japan, along with the United States and Australia, are part of the Quad, which aims to counter China’s increasing influence in the region. India and Japan are strengthening their relationship, particularly in defence and strategic matters, as both countries face challenges from a powerful China. India has refrained from blaming Russia for the war and is seeking a diplomatic solution while increasing its purchase of Russian oil. Japan also aims to enhance the maritime warning and surveillance capabilities of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries and hopes for active collaboration with India to develop infrastructure such as ports in Asia and Africa.

Maritime security in the Indo-Pacific reveals a complex tapestry of trade networks, colonial influences, and evolving power dynamics. Pakistan navigates alliances and partnerships to protect its maritime interests and maintain regional stability amid territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas. The strategic significance of Gwadar Port in Sino-Pakistan relations cannot be overstated. As an alternative to the Malacca Dilemma, Gwadar offers a crucial route for Chinese energy imports, potentially alleviating China’s reliance on shipments through the Malacca Strait. This strait, positioned between Sumatra Island and the Malayan Peninsula with Singapore to the east, poses a strategic vulnerability for China due to Singapore’s closer ties with India and the US, which could threaten China’s energy supply and, by extension, its economic growth.

On one hand, Pakistan is facing challenges of internal security, cross-border terrorism, and the economic depravity of locals in Balochistan. On the other hand, Iran has also its challenges due to the strained relations between Iran and the US. If the US reinforces sanctions on Iran, India may be reluctant to jeopardize its relationship with the US, potentially stalling the port’s progress. India’s strong ties with Saudi Arabia, its largest crude oil supplier and fourth-largest trading partner (with bilateral trade around $40 billion), also pose a risk. The contentious Saudi-Iran relationship could pressure India to reconsider its involvement in Chabahar.

Additionally, India’s close relationship with Israel, a country unrecognized by Iran, complicates the situation, the hostile relationship between India and Pakistan remains a significant challenge for the Chabahar port project. Pakistan has a solid brotherly relationship with Iran and for economic development and peace in the region, both the Chabahar and Gwadar ports can be operated as sister ports. India and Pakistan can overlook their enmity for regional development. There is potential for Chabahar and Gwadar to complement each other in enhancing regional trade and connectivity if geopolitical tensions can be managed. Joint initiatives could help integrate regional economies and boost overall economic growth if cooperative frameworks are established.

In the current geopolitical dynamics, these ports are rivals in a broader struggle for regional influence. The Western bloc is making significant efforts to contain China’s rise, which is evident through potential block ades in crucial sea trade routes such as the South China Sea. Tensions in the region are also on the rise due to India-China skirmishes in the Siliguri Corridor (also known as Chicken Neck Corridor) and Ladakh.

Pakistan proposes and strives for peace in the region but not at the cost of its sovereignty. India’s strategic moves to establish influence in areas of common interest around Pakistan, including investments in Afghanistan and Iran, as well as attempts to control naval passageways from the UAE to Oman, highlight its ambitions. Pakistan, acting as a strategic balancer, must remain vigilant and strengthen its naval capabilities to counter India’s efforts to encircle and contain Pakistan’s trade routes. Therefore, it is imperative to enhance maritime security, reinforce strategic alliances, and bolster defence mechanisms to safeguard national interests against India’s containment strategies.