The Vision of Islam – Extract-10

So tell the tale — perhaps they will reflect. [Koran 7:176]

Tanzih and Tashbih

In the technical language of theology, especially as it developed after the seventh/thirteenth century, two terms are commonly employed to express the contrast between the perception of God’s nearness and mercy and that of his distance and wrath.[1] These terms are tanzih (declaring incomparability) and tashbih (affirming similarity). Tanzih means literally “to declare something pure and free of something else.” It is to assert that God is pure and free of all the defects and imperfections of the creatures. In the perspective of tanzih, God is so holy and pure that he cannot be compared to any created thing, including concepts, since all our ideas are created. The Koranic verse that expresses tanzih most clearly is “Nothing is like Him” (42:11). Divine names that are taken as expressing tanzih are the names of God’s essence already mentioned, such as Holy, Glorified, Independent, and Transcendent. But all the majestic and wrathful names can also be called names of tanzih, because they stress God’s difference from creation, the fact that he is infinitely beyond the petty affairs of the creatures.

Tashbih means “to declare something similar to something else.” It is to assert that God must have some sort of similarity with his creatures. If he did not, how could they have anything to do with him? God’s signs within the cosmos and scripture designate his attributes, such as life, knowledge, desire, power, mercy, generosity and provision. These attributes belong to God, but they are also found in created things. All divine names suggest some sort of tashbih, because they allow us to think that God is such and such. Although we know that “Nothing is like Him,” as soon as we name God we create a concept in our minds of what he is like. For example, as soon as we read in the Koran that God is Compassionate, we think of God in terms of our own understanding of compassion.

Even when we name God by a name of the essence, such as Independent, we understand that name in terms of our own ideas of independence. Every divine name suggests a certain tashbih, but the beautiful and merciful names of God stress tashbih much more than they stress tanzih. Hence names that tell us about God’s nearness to creation and concern for his creatures can be classified as names of tashbih. To say that God is merciful and loving is to stress that he is not distant and aloof; instead, he is close to and concerned with people’s everyday affairs. Names of gentleness and mercy describe a God whom people can understand and love. These names suggest that, like a caring mother, God stays close to his creatures and watches out for their every need. When someone is gentle, good, and loving, the normal human response is to reciprocate.

The perspective of tanzih affirms God’s oneness by declaring that God is one and God alone is Real. Hence everything other than God is unreal and not worthy of consideration. God’s single reality excludes all unreality. In contrast, the perspective of tashbih declares that God’s oneness is such that his one reality embraces all creatures. The world, which appears as unreality and illusion, is in fact nothing but the One Real showing his signs. Rather than excluding all things, God’s unity includes them. Often tanzih and tashbih are associated with the two divine names batin (Inward or Non-Manifest) and zahir (Outward or Manifest). In as much as the Real is Inward, all outwardness is unreal, and oneness is found only in the Real himself. But inasmuch as God is Outward, all outwardness is the Real. Hence the universe itself is real through God’s realness and one through God’s oneness. Both God’s incomparability and his similarity need to be kept in view. If God is far, he is also near. Although he is beautiful and stirs up love in the heart because of his beauty, his beauty is not like the beauty of any created thing. “Nothing is like Him.” In the midst of his nearness he is far, and in the midst of his similarity he is incomparable.

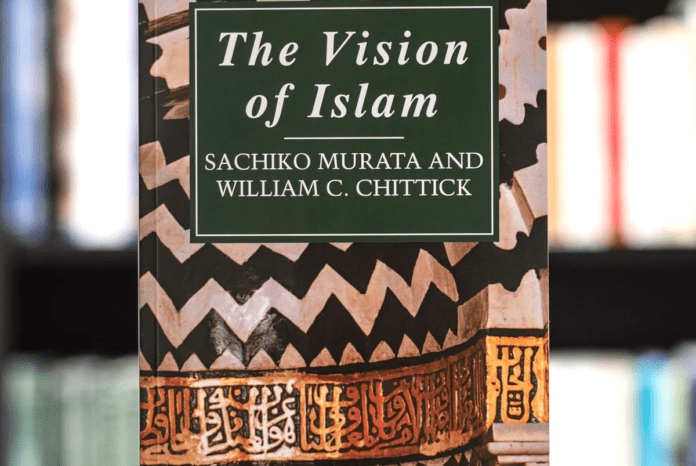

One way to understand the idea of incomparability is to conceive of an infinitely vast circle (Figure 1). God is at the center; He is the dimensionless central point that serves as the origin of the circle. The world that we experience is at the periphery, infinitely distant from the center. There are many worlds, and these can be pictured as a series of concentric circles, some closer to God and some farther away. All worlds have the same center, and all are cut off from the center because of God’s incomparability. Only the central point has no dimensions, and “Nothing is like Him.”

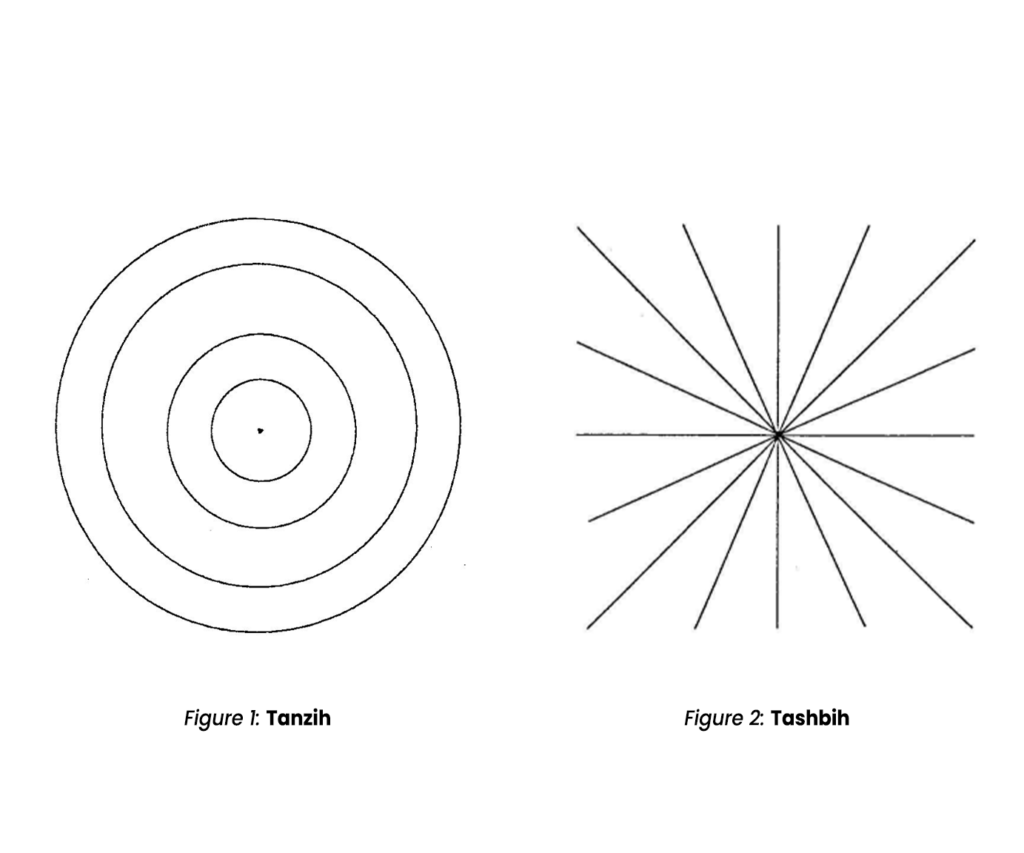

Meanwhile, every concentric circle is similar to every other circle. Created things share the same qualities, but God shares none of their qualities. In order to picture tashbih, we can use the same dimensionless point but now we need to imagine that the point has an infinite number of radii extending outward (Figure 2). Each creature in the universe is situated on a radius and is connected directly to the center, gaining its reality from the central point. The radii suggest God’s concern for creation through love, mercy, compassion, and kindness.

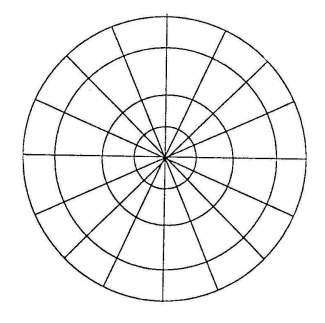

However, neither tanzih nor tashbih provides a complete picture of reality. The universe needs to be understood in terms of both perspectives simultaneously (Figure 3). Then we see that each thing is at once near to God and far from him, at once similar to God and incomparable with him. Each thing is confronted simultaneously with mercy and wrath, gentleness and severity, life-giving and slaying, bestowal and withholding, reality and unreality. This is tawhid.

The two perspectives of tanzih and tashbih, or God’s distance and nearness, are met constantly in Islamic texts and in the everyday life of Muslims. Let us cite one simple example. We have already referred to the Koranic formula “Praise belongs to God,” which is recited by Muslims on all sorts of occasions and in all sorts of contexts, since it expresses gratitude to God.

People recite it when anything good happens, when they eat or drink something, when they see something that pleases them. If they are a bit more careful in observing the Prophet’s Sunna than most, they will thank God for everything, for the bad as well as the good, for suffering as well as joy.

They will recognize that everything that comes from God should be acknowledged with gratitude. The Prophet said, “Praise belongs to God in every situation.” The formula of praise ties blessings back to God. It takes the signs in the cosmos and in the soul and ascribes them to their divine origin. Hence it affirms the perspective of tashbih, the nearness of God and his activity in all situations, his care and concern for human beings. Another commonly recited Koranic formula is “Glory be to God” (subhanallah). In contrast to “Praise belongs to God,” this formula stresses tanzih. It is uttered when any thought of ill occurs toward God or his activity, or when any suggestion is made that God might have motivations like human beings. The Koran often employs the phrase with this meaning, as when it rejects various opinions of pre-Islamic peoples. For example, “They have set up a kinship between Him and the jinn. . . . Glory be to God above what they describe!” (37:173).

These two formulas, which Muslims recite habitually and often without thinking about their meaning, express tanzih and tashbih in everyday life. What is significant is that both formulas are needed, since the human situation demands that God be perceived as both absent and present.

In short, tanzih and tashbih represent the two poles of tawhid. As we shall see, these two complementary perspectives need to be taken into account whenever we discuss such basic issues as the role of human beings in the cosmos, the nature of prophecy, and the return to God.

To be continued ……

Book Reference:

Vision of Islam[2]

[1] “The Vision of Islam” authored by Dr. Sachiko Murata and Dr. William C. Chittick delves into the multifaceted aspects of Islam, including practice, faith, spirituality (Ihsan), and the Islamic perspective on history, drawing from the teachings of the Hadith of Gabriel.

[2] Vision of Islam : اردو ترجمہ مکمل کتاب http://www.williamcchittick.com/ wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ Chittick-and-Murata-Vision-of-Islam-Urdu-Translation-by-Muhammad-Suheyl-Umar.pdf https://salaamone.com/vision/