Individual and collective social evolution is an interesting area of study. Famous historian Will Durant summarizes this process as “in ages of poverty and chaos, the will to believe is paramount, for courage is the one thing needful; in ages of wealth, the intellectual powers come to the fore as offering preferment and progress; consequently, a civilization passing from poverty to wealth tends to develop a struggle between reason and faith”.

In an era where faith reigned supreme, outright public rejection of faith was not an option as it would ensure a speedy death not only by a stroke of the sword but also crucifixion or burning at stake. In this environment, philosophers struggled to reconcile faith with reason. It was not a clear separation of competing ideas but a fluid environment. ‘Medieval Neoplatonic philosophy found comfort in certainty of revelation’ and blended philosophy with piety while ‘Aristotelian philosophy anchored on logic encouraged doubt’.

Plato’s philosophy viewed the world just as a shadow of a higher, truer reality that is eternal and unchanging. This reality is the ultimate reality, and the seat of all truth, justice, and wisdom. Aristotle’s philosophy recognized reality as the one experienced by man through his senses. It emphasized justice and government of the human world and the need to study it. This over simplified explanation of two schools shows why Platonic ideas were more acceptable to theologians and Aristotelian ideas suspect.

Muslim philosophers following Aristotle even though deeply immersed in theology faced the wrath of theologians compared to Neoplatonic philosophers. Medieval Rabbinic Judaism with a long history of problems with Hellenic ideas was also skeptical of the philosophy of all shades.

Intellectual currents of the Muslim world developed in distinct geographic areas. In Andalusia (modern day Spain and Portugal), away from the Muslim heartland, independent thought found a fertile ground. Abu Walid Muhammad Ibn Rushd (1126-1198) was the scion of an illustrious family of jurists and his grandfather and father served as Qazis (judges). Ibn Rushd followed them and became chief Qazi of Seville and then Cordova.

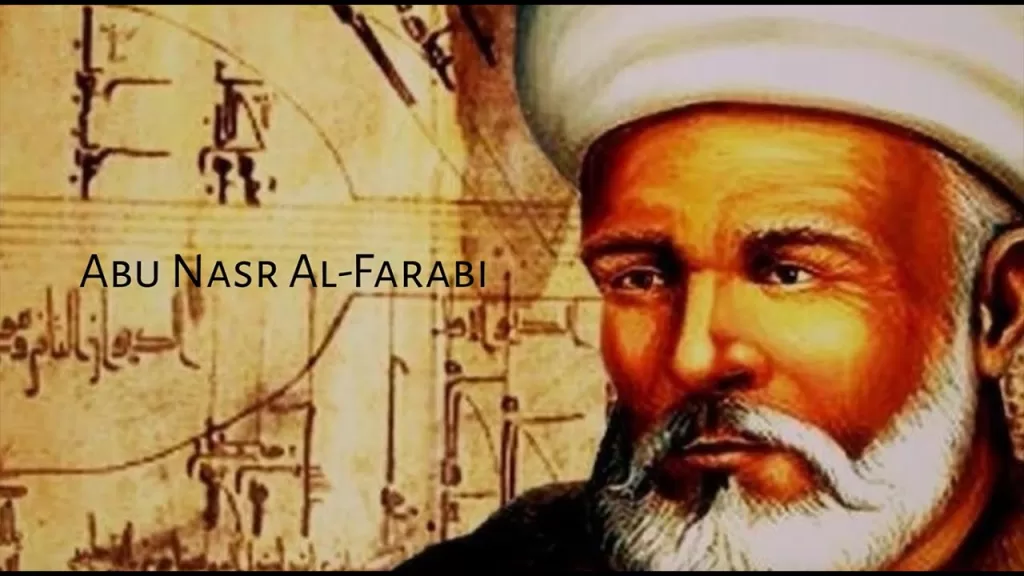

Ibn Rushd was the disciple of Aristotle and continued the Aristotelian tradition of Abu Nasr Muhammad al Farabi (870-950). Abu Hamid Muhammad al Ghazali’s (1058-111) Tahafut al Falasifa (Incoherence of the Philosophers) put certain beliefs of the philosophers beyond the pale. This serious charge of kufr (unbelief) put philosophers following Farabi’s Aristotelian traditions at serious risk. Ibn Rushd countered Ghazali in his two monumental works Fasl al Maqal (The Decisive Treatise) and Tahafut al Tahafut (Incoherence of the Incoherence). He refuted many charges of Ghazali against philosophers and argued that philosophers do not object to religious laws and consider it necessary for administration of a community for political tranquility. To refute the charges of unbelief, he combined religious inspiration with reason for harmony. He considered revelation and demonstrative sciences as different representatives of truth and not as conflicting ideologies.

Ibn Rushd influenced many Jewish intellectuals of the Hebrew translation period of 13th century onward, and these followers were known as Averroists. The Jewish Averroist Isaac Albalag (lived in second half of thirteenth century) was deeply influenced by Ibn Rushd but also wrote the first Hebrew translation of Ghazali’s doctrines of philosophers in 1292. Later translations and commentaries by Jewish authors resulted in Ghazali replacing Ibn Rushd among Jewish intellectuals as Ghazali put revelation above philosophy making it acceptable to theologians.

Andalusia provided the prosperous Jewish society living under relatively peaceful la Convivencia (coexistence) to embark on the journey of philosophy. Musa bin Mamun known in English as Moses Maimonides (1135-1204) was born in Cordova to an illustrious family of deeply religious Jews steeped in tradition of learning. In 1159, he was forced first to migrate to Fez in Marrakech and then Cairo when puritanical Berbers captured Cordova. His Kitab al-Siraj (Book of the Lamp) published at the age of thirty-three elevated him to a commentator of Talmud. His Mishna Torah (Repetition of the Law) is the standard text of yeshivas (Jewish religious seminaries) all over the world even today. His religious work was written in Hebrew but his philosophical works Dala’lat al Hai’rin (The Guide for the Perplexed) and Makala fi Sina’at al Mantiq (Treatise of Logic) were written in Arabic and later translated in Hebrew.

Maimonides collected all the commentaries of Ibn Rushd on Aristotle and introduced Ibn Rushd to the Muslim east. He tried to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinic Jewish theology. In this effort, he tried to rationally explain events in biblical texts. However, Maimonides work of reconciliation of revealed Judaic laws with philosophy followed Ghazali’s footsteps. He believed that ‘social order was impossible without belief in divine origin of the moral code’. He called some of revealed truths that could not be explained by reason as Sitre Torah (Secrets of the Torah). He believed that a monotheistic and virtuous non-Jew would go to heaven. On the other hand, he would not allow any room for a heretic going to the extreme that a Jew who repudiated Jewish law must be put to death.

Ibn Rushd and Maimonides were the products of their time where communities were structured around religious identity. Both were polymaths and not only great scholars of religious sciences but served as jurists judging complex questions pertaining to religious laws. Both were aware of the incompatibility of rational science and reason with some aspects of the revelation that could not be explained by the scientific knowledge of their times. They tried to explain but advised that thorny issues not to be discussed in public but only with selected learned few.

Muslim and Jewish communities had ambiguous relationship with their respective sages. They were praised for their intellectual excellence and gained a sizeable following, but both were also condemned by their respective religious communities for breaking out of accepted traditions. Political upheaval of the times had a profound influence on religious thought and practice. In tumultuous times, faith usually retreats into the comfort of familiarity and views any innovation as a threat to the faith and by extension to the religious community.

Andalusia of the eleventh century saw a struggle between the disintegrating Umayyad caliphate and the tai’fa (faction) independent mini states. There was a multi-dimensional power struggle among Arabs, Berbers, Hispano-Arabs, and slave soldiers (Saqalibah) making alliances with neighboring Iberian Christian and North African Muslim kingdoms. Almoravids followed by puritanical Almohads Berber dynasties from North Africa took control of Andalusia. Almohads used religion as a source of legitimacy to rally support of the community and Muslim religious authorities. In this context, persecution of minorities and repression of any doctrine like philosophy that is suspect is the natural outcome.

Disintegrating kingdoms seek the aid of theologians and later give their support at the expense of independent thought. In the east, Caliph Abu al Muzaffar Yusuf bin Muhammad al Muqtafi known as al Mustanjid (r. 1160-1170) in Baghdad ordered burning of philosophical works of Ibn Sina. In the west, Hisham al Mu’ayyad Billa’h (r. 976-1009) ordered burning of all books of philosophy and in 1194, Almohad Emir Abu Yusuf Yaqub al Mansur (r. 1163-1184) ordered burning of all philosophical works of Ibn Rushd. However, the tragic fact is that society loses on both fronts. The kingdom is lost to the invaders while society loses independent thought that is the fountain of revival. In the west, Christians completed Reconquista of Andalusia (only exception was Granada), the Crusaders captured Jerusalem and finally the Mongols vanquished Baghdad with complete destruction of the city.

Ibn Rushd in his later life was condemned as a philosopher, exiled to Lucena and his works were burned. The flame of speculative philosophical thought in Muslim world dimmed after the death of In Rushd. Muslim intellectual life turned towards theology in its traditional mode. Those who found this task devoid of spiritual essence turned towards Sufism (Muslim mysticism). In the Muslim world philosophy retreated except for Ibn Sina whose philosophical views were compatible with traditional religious beliefs. In the Muslim world, critic of philosophers, Ghazali ruled supreme. A 13-century report declared Ibn Rushd as ‘the imam of philosophy of our time’ but added that philosophy as ‘a science is detested in Al-Andalus. One cannot study it in public, and for this reason the writings on this subject are concealed’.

Maimonides was forced first to leave for Fez where the Jewish community was pressurized to convert to Islam and later, he settled in Egypt then ruled by the Ayyubid dynasty. He became the head of the local Jewish community. Maimonides efforts of synthesis between Greek philosophy and Jewish faith generated a strong opposition from Jewish traditional religious authorities in the east and the west known as “Maimonidean Controversy”. Rabbis of northern France banned study of philosophy including Maimonides works that were later burned by Dominican priests. After the death of Maimonides, Jewish intellectual life struggled over his legacy. Following the Muslim example, Jewish learning retreated into the yeshiva limiting itself to the study of Torah. Those yearning for spiritual meaning of faith turned towards kabbalah (Jewish mysticism). Historian Will Durant summarizes the era, “after its escapade with reason, the Jewish soul, haunted with theological terrors and an encompassing enmity, buried itself in mysticism and piety”.

Suppression of reason and independent thought did not prevent the destruction of the empires but prevented regeneration as communities retreated into the comfort of certainty of theology. Whatever that could not be explained by theology was submerged in the ecstasy of mysticism. Retreat of reason allowed proliferation of theological discourse and mystic brotherhoods in Muslim and Jewish communities.

Ibn Rushd had profound influence over Jewish and Christian philosophers and almost all his available works were translated in Hebrew and Latin. In time, his commentaries replaced the original works of Aristotle and just as Aristotle was known as “The Philosopher”, Ibn Rushd was known as “The Commentator”. He had major influence over Christian philosophers who sowed the seeds of Renaissance. Today, Maimonides is fully embraced by all streams of Judaism from traditionalist to rationalist to the mystics. The famous saying is that “from Moses to Moses, there was no one like Moses” meaning that from Prophet Moses to Moses Maimonides, there has been no one like them. Interestingly, Ibn Rushd and Maimonides lived in the same era but never met and if they had met, both would have been delighted. They have re-united posthumously when Spain embraced its two illustrious sons and erected statues of Ibn Rushd and Maimonides in Cordova.

“If you have knowledge, let others light their candles in it.”

Margaret Fuller

Notes:

• Will Durant. The Age of Faith (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1950

• Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora (Editors). A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations – From the Origins to the Present Day (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013)

• Hamid Hussain. Abu Hamid Muhammad ibn Muhammad al Tusi al Ghazali. Defence Journal, February 2023.