India’s high ranking in dairy production internationally has made it one of the leading countries for dairy production to be an essential part of their economic development. The central theme of the book Mother Cow, Mother India has highlighted the growing importance of New Delhi in the international dairy markets, where it has become a potential player. The central theme of the book revolves around the questions of New Delhi’s high standings in the list of some countries producing various dairy products parallel to exporting a larger amount of its domestically produced beef to many other countries.

A formal report of the US Department of Agriculture From Where the Buffalo Roam confirmed the Indian leading role in international beef export (p. 30). Akin to the report of the US Department of Agriculture, various other academic studies emerged from other countries, proving New Delhi’s increasing reliance on the role of cows and buffalos in supporting the Indian economy. These dairy cattle are strongly associated with India’s traditional religious and societal attributes.

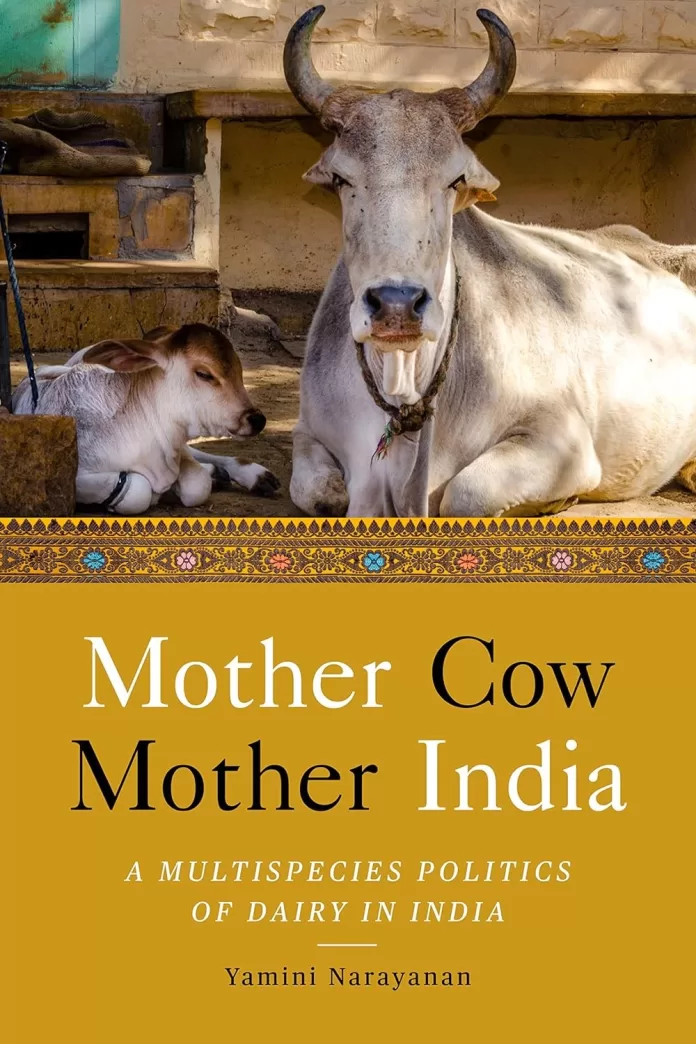

The writer of the book, Yamini Narayanan, tried to adopt a non-conventional academic lens to evaluate the role of cows in Indian social, political, and economic frameworks due to having an exceptional standing in the emerging field of South Asian animal studies. She is a renowned academic figure with a reputable standing in the international scholarly communities while serving Deakin University. This Australia-based university granted Narayanan an academic Award for Mid-Career Research Excellence in 2019. Narayanan’s academic potential has allowed her secure sufficient financial support to complete an animal study in India in which she relies mainly on primary sources of information collected from different directions through a comprehensive fieldwork.

The book under review is a reflection of Narayanan’s insightful and critical examination of India’s increasing dairy production potential, which is directly linked to the sacred status of domestic cows. The role of the state’s ideology and its impacts on society play a vital role in this scenario because all the cows have become a supporting point of the Indian economy, whereas the sacred status is granted purely to the domestic cows, which are called the desi cows (native breed). The non-native breeds, such as Jersey and Holstein, are equally important for economic purposes and are considered demonic species (p. 88).

The book talks about the imprint of the Indian classical caste system on cow politics at the domestic level. It is a study of an Indian paradoxical socio-religious and socio-political behaviour regarding the scared status of cows and their roles in the contemporary beef politics of New Delhi which mainly started with the arrival of Prime Minister Modi in Indian politics in 2014. The main structure of the book is divided into eight chapters apart from a detailed introduction consisting of starting forty pages. The introductory pages provide a comprehensive account of different arguments explaining the nature and characteristics of cow politics in India parallel to describing a countrywide culture of cow abuses in India beyond their sacred identities.

The book’s first chapter starts a debate about New Delhi’s internationally increasing role in milk production, beef export, and leather products. The increasing strengths of these industries in the Indian economy are attached to the slaughtering of bovines, which coexists with the prohibition of cow-killing legislations in the country (p. 41).

The subsequent chapters continued the debate and covered different aspects of cow politics against certain population groups and the continuation of weak implementation of the cow protection law of New Delhi across the society. These weak policies can be measured by the miserable conditions of cows with inadequate facilities and shelter homes for cows. The insufficient arrangement of cow protection centers across the society is a bitter reality of the country, which needs more serious attention in the New Delhi-based policymaking circles.

The first four chapters of the book describe various types of cruel treatment of cows in India despite having a vast countrywide network of cow-shelter centers (Gaushala). The Gaushala refers to a nationwide shelter complex for old, sick, and retired cows and bulls, which contradicts the consecrated explanations of animals in Indian society (p. 04).

The contradiction between the sacred status of cows and their suffering in the shelter homes reveals the financial constraints of Indian society, which are overwhelmed by the ideological association of the society with the domestic cow breeds. The quest of validating this argument led the author of the book towards the inclusion of various sets of empirical data collected from different visits of leading cow-shelter centers of the country.

The book’s analysis contains several interesting arguments, attractive phrases, and fascinating sets of information, such as the mention of the White Revolution or the National Dairy Plan of India, commonly known as Mission Milk (p. 68).

The toxic diets of animals comprise plastic waste in the country, as India has recently appeared in the list of countries facing the problem of plastic waste management. Insufficient animal food supplies have compelled the animals to rely on toxic diets, which augment the suffering of animals in the subcontinent, where India is taking the lead.

Moreover, the concepts of Hinduizing dairy and Islamicizing beef have become a gravitational point of cow politics in India (p. 180). The role of trafficking and slaughtering further augment the challenges of cow protection in India, and both dimensions are covered in the sixth and seventh chapters.

Apart from varying explanations of the cow politics or beef politics in the subcontinent generally and between New Delhi and Islamabad specifically, the analysis in the book treats the dairy and beef industries of South Asia as the most profitable segments of India-Pakistan politics.

Akin to these facts, the arguments in all chapters are heavily equipped with various interesting facts and convincing statements collected by the author from several interviews and informal conversations with the people attached to the dairy industry and cow-shelter centers of India. The inclusion of empirical data sources in all chapters made it an academic effort to advocate the voices of animal rights in India, which are generally neglected in society.

Based on the abovementioned features, it is appropriate to maintain that this book is an exceptional account of different arguments concerning the inconsistent cow-legislative decisions of the Indian parliament and the rising gap between cow-concerning policies of the government and their appropriate application in society.

The book primarily emphasizes cows’ cultural, religious, and economic attachments to the Indian state system. According to the author of the book, the cow politics of India has become a serious issue for the Muslim and Dalit communities, whereas the Indian state system ignores the suffering of cows in the custody of the Hindu population. In this way, the main idea of Narayanan’s work underlined the growing complexities of the human-animal relationship in India while exclusively emphasizing the role of Indian domestic cows, which are purely a scared class contrary to other breeds.

The varying contexts of all arguments in the book present an exciting account of animal rights and cow politics in India, which is an area of less scholarly attention in India due to various societal taboos and political pressures. The author of the book tried to raise her voice on an issue of immense importance for Indian society, where the sacred status of cows has been transformed into the modern economic trends of the world. Thus, it is an appropriate study to comprehend a different dimension of Indian society because it is a pioneer work on South Asian animal studies.

People interested in understanding the prevalence of the traditional animal-centric societal practice of the right-wing Hindu population in India can find this book as an appropriate academic account explaining the complexities of Indian society in the contemporary world of the post-twentieth century.