The story of Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan is one of remarkable valour and unwavering commitment to his country, Pakistan. Born on April 7, 1940, against the backdrop of World War II, his family had a long-standing connection with the military. His father and elder brothers had all served in various capacities in the armed forces, instilling a sense of pride and duty toward the uniform from a young age. With roots in the village of Jajja, an area economically dominated by non-Muslims before the partition of the subcontinent, access to quality English education was a rare privilege for young Muslims. This historical backdrop further fuelled Lt. Gen. Lehrasab Khan’s determination to rise above limitations.

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan’s journey began in a local school in Jajja, and the absence of English education in Muslim schools led him to vernacular institutions. He narrates the stark economic disparity between Muslims and non-Muslims in his region before the partition, where non-Muslims held sway over the markets and finances, often lending money to Muslims. This financial control translated into a form of subjugation, as Muslim debtors had to clear their debts before they could harvest their crops. Partition brought about a change, with retaliation leading to the burning of non-Muslim towns, including the home of a prominent figure, Master Tara Singh. Their dominant hold on the region was dismantled, and the economic backwardness of the area was starkly evident.

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan’s educational journey took him to schools in Sialkot and Sukho. The historical context of his region, the recruitment area for the armed forces, played a crucial role in shaping the psyche of its people. With a legacy of service in his family dating back to 1868, he eventually joined the military, continuing the family tradition. His commitment to serving the nation manifested in his service during the 1965 and 1971 wars. Beyond his military career, his sense of duty extended to his native village, Jajja. Despite its historical neglect and underdevelopment, Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan undertook the ambitious endeavour of establishing a state-of-the-art cadet college there, ensuring that the local youth, particularly girls, could access quality education. His journey from Jajja to serving Pakistan’s military, followed by his philanthropic efforts in his village, exemplifies his unwavering commitment and extraordinary contributions. Knowing a war hero like him is an absolute treasure and his efforts for his country must be acknowledged. Here is the first exclusive interview for Defence Journal:

Unyielding Valor: The Portrait of Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan

Q. Could you share some insights into your personal life, your family, and your experiences?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: I was born in Jajja village on April 7, 1940, during World War II. At that time, my elder brother was stationed in Burma, and my father, who had served in the 1st World War in Basrah, Iraq, had also contributed to the military legacy of our family. Another elder brother of mine, who later joined the army, was seriously wounded in Burma during World War II but made a remarkable recovery after the war’s end, rejoining his unit. It was during my second-grade schooling that I had the opportunity to move to Sialkot, where my brother was stationed, a place that marked the beginning of my journey into the armed forces. Before I entered the army in 1960, I received my primary education at a local school in Jajja. At that time, English education was scarcely available in Muslim schools in this region, and I, like many others, attended vernacular schools.

The pre-partition era was characterized by the economic dominance of non-Muslim communities, particularly Sikhs and Hindus, in the Jajja region. Areas like Mandra, associated with Master Tara Singh, exemplified this dominance, with places such as Harnal and Sukho having a significant non-Muslim population. The ability to access English education was largely confined to non-Muslims, posing a challenge for Muslims to benefit from such opportunities.

In this economically backward region, there was a deliberate lack of development, despite being the recruitment area for the armed forces. It was a matter of pride for the local populace to serve in the army, and the Potohar region up to Attock, nestled between the Jhelum and Attock rivers and extending to Mianwali, was the Marshall Area. World War I and World War II saw substantial military contributions from this region, further nurturing the sense of pride associated with wearing the uniform.

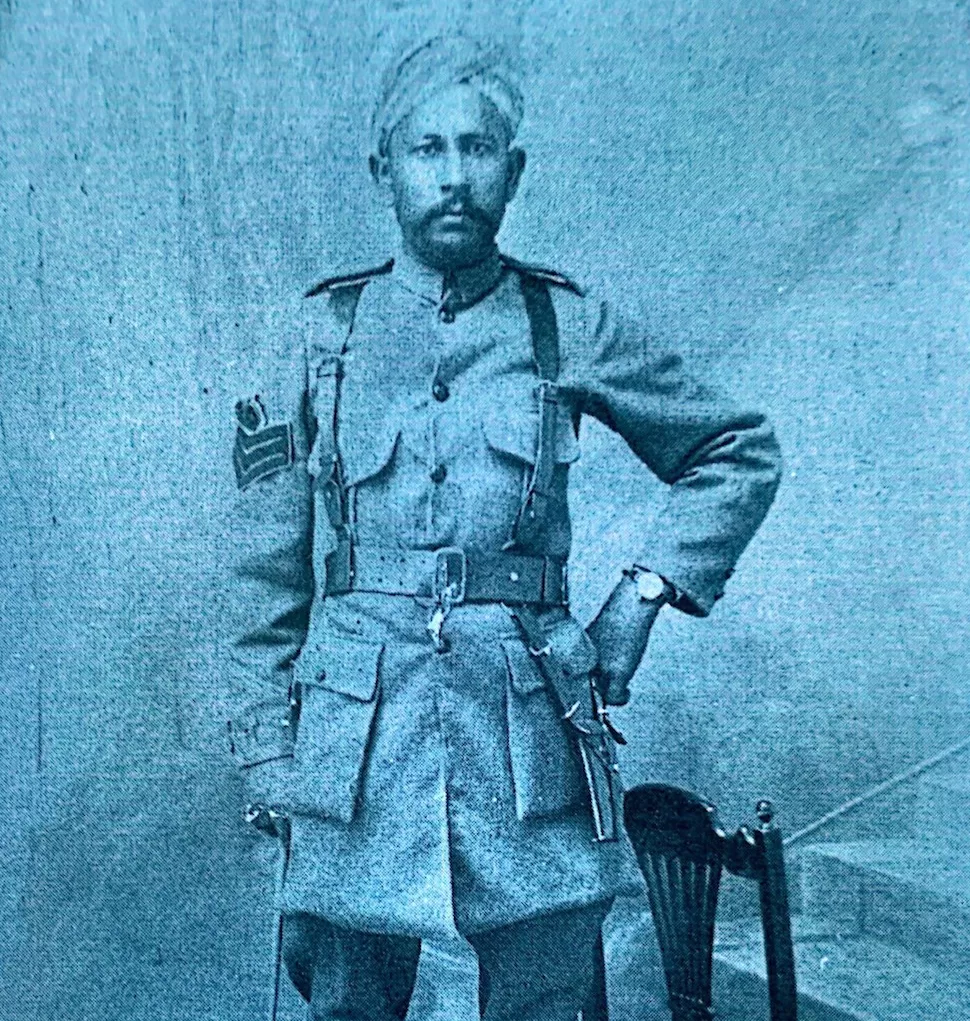

Father of Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: Mirza Khan (1920)

My journey continued as I walked five kilometers to reach school during my first grade. Subsequently, in my fourth grade, I gained admission to Islamia High School Sukho, formerly known as Khalsa High School Sukho, which had been managed by non-Muslims before the partition.

This shift in management marked the beginning of a new chapter in the school’s history. I completed my matriculation at this institution and later pursued my education at Government College Rawalpindi, located on Asghar Mall Road. Eventually, I secured admission to the Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) in 1960, embarking on a path of service to my country, following the footsteps of my family members who had served in the armed forces. My family’s legacy of military service commenced in 1868 when my grandfather joined the army, continued in 1895 when my father enlisted, and extended to both of my brothers who served in the army during World War II. This proud tradition was perpetuated further when my son, an orthopaedic doctor, joined the army before my retirement.

After World War II, South Asia transformed, gaining independence as sovereign states following their support to the British during the war. In 1947, India and Pakistan emerged as independent nations, each with its armed forces. India’s military was larger and more robust compared to Pakistan’s, which led to a strategic advantage. Additionally, India’s proximity to the small Himalayan nations provided a sense of security, while a friendly relationship with China in the 1950s reinforced the region’s stability. However, the 1962 conflict in the NEFA area challenged India’s security perceptions and prompted a re-evaluation, leading to the expansion of its armed forces. The post-World War II era also saw the emergence of Mao Zedong’s China, altering the geopolitical dynamics in Asia. India, facing internal and regional challenges due to the partition, had to adapt its policies. While Pakistan built strong relations with Western powers, India cultivated a strategic partnership with the Soviet Union for economic and military support.

It was during 1964 that the people of Kashmir who had a genuine desire to join Pakistan, by expression of their political will, were gradually mustering support in line with the 1948 UN resolution which demanded the holding of a plebiscite to exercise their right of self-determination and choose between India and Pakistan as some other states had done after partition. To maintain a peaceful working relationship with its neighbours in the sub-continent, India in the early 60’s made all gestures to give the impression that the resolution of Kashmir was in the interest of the region, in general, and India and Pakistan, in particular.

The visit of Sheikh Abdullah to Pakistan, as the leader of Kashmiris, was a step in the right direction in search of a negotiated solution but the sudden death of Nehru adversely affected the new initiative and the status quo prevailed. Kashmiri youth were gradually getting activated to fight for their political rights and this created the environment for the leadership of Pakistan to actively support the Kashmiri struggle for freedom, hence, Operation Gibraltar.

Operation Gibraltar:

In the summer of 1965, I found myself amid a turbulent and challenging situation as part of Operation Gibraltar. This operation was driven by the deep-rooted support among Pakistanis for the Kashmiri cause and a desire to help our Kashmiri brethren achieve their freedom from Indian occupation. The idea of Operation Gibraltar was conceived in 1964, aiming to reinforce the Kashmiri freedom struggle across the ceasefire line by sending armed volunteers from Azad Kashmir.

The proposal received mixed reactions among Pakistan’s civil and military leadership, but eventually, it gained approval. Civilian youth from Azad Kashmir were enrolled and underwent a brief training program to prepare them for this mission. However, the volunteers were not fully prepared for the challenging task ahead, and there were deficiencies in the command element. Looking back, it’s clear that not enough groundwork was done across the control line to create the necessary conditions for a successful uprising in Kashmir.

Operation Gibraltar officially commenced in late July or early August, and I received my posting to report at Division Headquarters in Murree around the end of the first week of August. Upon arrival at Murree Division Headquarters, I began to comprehend the gravity of the situation and my role as a soldier in this operation. I was a Lieutenant at that time, and overnight I was shifted to Murree. There, I met with Gen. Akhter Malik, who interviewed me and delivered a morale-boosting speech, saying, “You have a great opportunity, and you should be proud of yourself.” I requested my superiors to send me to Rawalakot via Rawalpindi so that I could buy a pair of clothes (Shalwar Kameez) and quickly reorganize myself for the challenging task that lay ahead. So, I was assigned to the Gibraltar force and sent to the occupied territory. I crossed the Azad Pattan Bridge into Azad Kashmir and reached Rawalakot in the early morning hours. There, I was met by Brigade Commander Brigadier Ishaq, who informed me about my new unit, the 10 Azad Kashmir Regiment, and its mission in the 1965 War. I spent the next night at Rawalakot.

The mission was to reach Gulmarg after crossing the Pir Panjal Range from Neelkanth Gali and join the Nusrat Force already operating in the area. The handpicked individuals for the battalion had already gone with the Nusrat Force, so we had to train recruits rigorously. When I joined the unit, it was concentrated and about to move into Indian-Occupied Jammu and Kashmir to fulfil its mission. The battalion was tasked with securing Dogi Forest, which would serve as a hideout for future operations. We succeeded in this mission, and the rest of the battalion joined us after a few days. The entire battalion was readjusted, and we established defences around Dogi Forest.

As the summer of 1965 progressed, a growing movement in support of Kashmiris struggling under Indian occupation gained momentum in Azad Kashmir. However, this ultimately led to a full-fledged war between India and Pakistan. Amid the War, the Indian forces launched a major offensive in the Haji Pir Pass area, threatening to link up with the Poonch Garrison and cut off the Uri-Poonch bulge held by Azad Kashmir forces since 1948. This forced the Pakistan Army to adjust its positions in this sector and bring in reinforcements from the Chamb-Jaurian sector. Our battalion was tasked with holding key positions in the Uri Poonch sector. We faced numerous challenges, including a lack of proper equipment, insufficient logistics support, and an unprepared civilian population in the occupied territory. Under these circumstances, our battalion was ordered to move to the forward Kahuta area for a new operational role. Two companies, led by Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah and me were tasked with reaching the Lunda feature to intercept enemy convoys supporting Haji Pir Pass. The threat was imminent, and we moved quickly. Our mission took us to the Lunda feature, where we realized that the enemy’s line of communication was too distant for us to pose a meaningful threat. It was also evident that the local population in occupied Kashmir was unprepared for any significant role in our operation. Also, our mission faced logistical and operational challenges. We encountered civilians guarding a ration dump that had been established for Gibraltar forces but had little left to offer. We were then ordered to redeploy to the Forward Kahuta area because the Indians had captured Forward Kahuta. The situation was rapidly changing, and our troops needed to be in a more defensible position. Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah and I moved forward as well, keen to confront the challenges together.

On August 22, 1965, a reconnaissance mission was led to Neelkanth Gali, a flat terrain covered in snow. The Indian forces attacked, but the battalion managed to open fire, taking them by surprise. The next day, a company was tasked to secure Neelkanth Gali for the battalion’s passage into Indian-Occupied Jammu and Kashmir. However, logistical challenges, ration shortages, unfit uniforms, insufficient currency, and small-calibre weapons posed challenges. The Muslim population was reluctant, and Indian forces initiated an offensive near Haji Pir Pass. The battalion was ordered to move forward to Kahuta, intercept enemy convoys near Lunda feature, and intercept enemy convoys near Lunda feature. They were approached by civilians guarding a depleted ration dump and offered two rifles. Communication with headquarters was severed, and they arrived in Kahuta on August 30, 1965, with high morale.

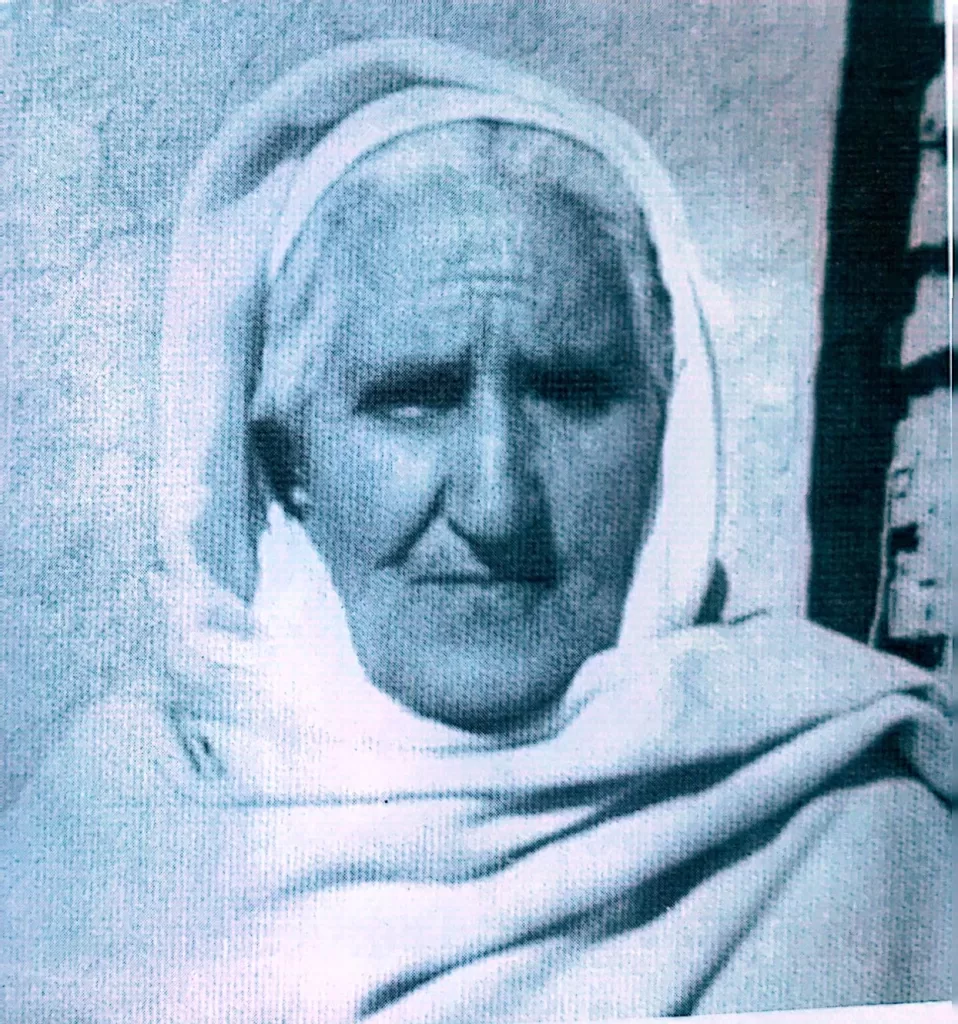

Mother of Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: Noorjehan (1977)

I received information that Indians had reached Aliabad from Forward Kahuta and were advancing. Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah remained at Forward Kahuta while my company moved towards Aliabad, climbing the Sar Feature and reaching Ghore Mar/Gitlan. The rest of the battalion had reached the home bank of Betar Nullah. On August 31, 1965, I met Lieutenant Naeem of the 20 Punjab Regiment at Sar Feature. He had not eaten for three days, so I shared Chana (Roasted Chickpeas) and Gurh (Jaggery) with him. We then went to the company headquarters of 20 Punjab Regiment at Sar Feature commanded by Major Nawaz. Later, Lieutenant Naeem was fatally injured by an artillery shell, and the rest of the battalion joined my company at Betar Nullah that night.

We received orders to deploy at Betar Nullah. Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah and I were tasked with crossing Chanjal Bridge and deploying on the other side. The Indian forces were planning to link up from Chand Tekri and Ziarat at Ghore Mar. The battalion stayed in this position until September 7, 1965.

The morale of the troops was high, and we prepared our defences diligently. The news of President Ayub Khan’s address on 6th September served as a significant source of motivation for us, further igniting our spirits. As the war continued, our battalion faced numerous challenges and threats. We were engaged in combat on various fronts, defending our positions fiercely. On September 7, Ziarat came under pressure, and Shahbaz Khan Feature was captured by the Indians. It was a daunting task, given the superior numbers and resources of the Indian forces. Despite the odds, we remained resolute and determined. On September 7/8, Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah repulsed an Indian attack from the Bedori side. On September 8, Indians captured Chand Tekri, and on September 9, Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah’s company came under attack. My company also faced an enemy threat. Eventually, we were ordered to fall back to the home bank of Betar Nullah.

On September 10, 1965, our battalion received orders to deploy on Ghore Mar/Gitlan in coordination with the 20 Punjab Regiment. We fortified our positions and prepared for the Indian thrust. It was a challenging task, but our morale was high. It was during this time that I received a heartfelt letter from my elder brother, Altaf Hussain, urging me to perform in a way that would make our family proud. On September 17/18, Indians reached Forward Kahuta and had control over the area. On the night of September 19/20, the Alpha Company of 20 Punjab Regiment came under attack from Sar feature. I was ordered to be ready for a counter-attack if needed. On September 20, Indian forces launched a probing attack, and I was ordered to position my company on the reverse slopes of Gitlan to reinforce the position. On the night of September 20/21, Indians attacked Gitlan, and my company was ordered to counter-attack to recapture it. Despite initial hesitation, my troops and Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah joined me, and we successfully retook Gitlan. Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah’s bravery and support were crucial to our success.

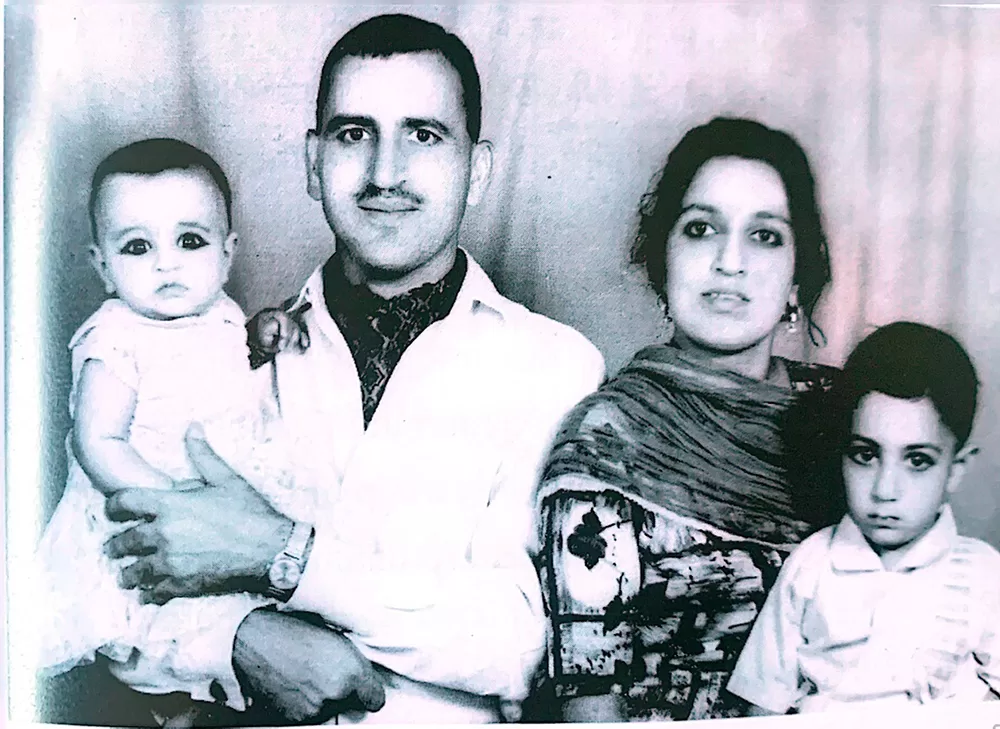

Jessore 1970 with my Wife, my Son Waseem and my Daughter Iram

On September 21, we repelled another Indian attack. The ceasefire was set for September 23, and I was given artillery support, which was the first time for our unit. A few hours before the ceasefire, Indians made another move, and we engaged them successfully.

After the ceasefire on September 29, 1965, a Canadian UN Military Observer named Major Blanche visited from the Indian side and met with me. He requested that I vacate my forward platoon position, as it was designated to be under Indian control post-ceasefire. He showed me a map illustrating the ceasefire line between my forward platoon and two platoons in the main position.

I explained to the UN observer that the Indians had been unable to capture this position during the conflict, so it made no sense to vacate it after the ceasefire. I refused to leave the position, and the UN observer left feeling disappointed. This issue escalated to a higher level, and our brigade was instructed to gather evidence against me for insubordination. I attempted to explain my position to my Commanding Officer but couldn’t convince him. However, I received news that the Commander of the 6 Brigade planned to visit my company and personally inspect the forward platoon’s position. When the Brigade Commander and my Commanding Officer arrived, I had the chance to brief them on-site. The Brigade Commander understood the practical situation and the tactical advantage held by our troops, and he ordered a status quo. He commended my decision during the UN observer’s visit, stating that he would have made the same choice if in my position.

Although we were initially organized and equipped for guerrilla warfare, operational necessities led us into conventional warfare without adequate logistical support. This made us vulnerable at times, impacting our operational capabilities. Despite these challenges, we never allowed the enemy to exploit our weaknesses.

We maintained an aggressive posture and managed to make an impact, achieving our objectives despite facing a significant disparity in troops and equipment. This was evident from a statement by Lieutenant Colonel Shah Beg Singh, the commander of the 3/11 Gorkha Battalion, who expressed that if he had Company Commanders like Lieutenant Lehrasab Khan or Captain Zulfiqar Ali Shah, he could have captured the Ghore Mar-Ziarat feature.

Throughout this operation, we demonstrated unwavering courage, camaraderie, and determination, which led to the successful defence of our positions and the accomplishment of our mission. Our experiences during Operation Gibraltar were a testament to the indomitable spirit of the Pakistani soldiers who were willing to go to great lengths to support the Kashmiri cause.

If I had to summarize Operation Gibraltar, I would say that “it was an ambitious plan with improper execution.”

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: I joined the army in 1960 as a cadet and was commissioned in the army in 1963. My first posting was to East Pakistan in an infantry battalion, which was 100% Bengali. Ikram Sehgal was in 2nd Bengal, and his father also commanded 2nd Bengal. I was in 1st Bengal, Senior Tigers. It was deployed at Comilla. There was a cantonment in Comilla before the partition. During World War II, the 14th Army of the British Indian Army was raised there to counter the Japanese threat. They launched the counter-offensive from the Chittagong area, recaptured Burma, and then pushed the Japanese back to Japan. This army was raised in Comilla. So, Comilla was a readymade cantonment for the Pakistan Army after partition, and there was a brigade there. This Battalion was part of that Brigade, and I joined that battalion at Comilla. After seven months, our Battalion was transferred to Bannu. After one year, it was shifted from Bannu to Lahore, so at the end of 1964, we moved to Lahore, and in 1965, we were in Lahore. We were deployed near Bedian in Lahore, between Bedian and Kasur on the Bambawali-Ravi-Bedian (BRB canal) just before the War started.

Q. Tell us about your association with Ikram Sehgal and Pathfinder Group, particularly in terms of the company’s dedication and role in offering free education to the children of marginalized employees within the company.

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: He (Ikram Sehgal) was the in-charge of the Rear Party of 1st Bengal and I was the Officer Commanding the advance party as a Captain. Normally, the 2nd In Command goes, or the most senior Major goes as the OC advance party. But the Commanding Officer (CO) had sent me there, even though I was the junior-most Captain and lacked experience because both regiments were of the Bengal Regiment. So, the CO told me not to have any disputes with them, and to accept whatever they handed over to me.

When the CO came to Lahore, Ikram Sehgal had to hand over everything to me, and I had to take over all the things. The CO instructed both Ikram Sehgal and his CO that whatever they handed over to me, and if there was any deficiency, we should send the list to the CO in Lahore, and they would rectify it. This was how we first met, and it marked the beginning of a long-lasting relationship.

As far as the efforts made by the Pathfinder Group and the contributions of Ikram Sehgal, particularly in terms of his dedication and role in offering free education to the children of marginalized employees are concerned, I would say that the qualities of this initiative and the community to which it is related, and also the hard work and the efforts of Ikram Sehgal are very difficult to weigh it. They cannot be quantified. Number two, he has had very serious setbacks in life but he didn’t give up. The way he has handled his affairs, personal and professional, is exceptional and Allah has given him this spirit.

This is the result of his good deeds. This initiative is a small part of the huge efforts he is involved in. He is doing much more than this. But he has sponsored the needy and marginalized students here. I think this investment is very good for the future of these students. It is a charity.

Q. Your account of the participation in the 1971 war in East Pakistan?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: 1971 is a tragedy for us. It was a very huge tragedy because we lost a part of our country. But I think we lost the basic theme of independence. If one has to be honest with his analysis, the Pakistan movement didn’t start from Jhelum, it didn’t start from Rawalpindi or Jajja. It started from the streets of Dhaka. When somebody doesn’t want to live with you, then there is something wrong and somewhere we need to look into that. In an Indian attack during the war in 1971, I was very seriously wounded by a mine blast on the border and my both kidneys were damaged, and my urinary bladder, my right arm, my right leg, and my nerves were damaged. There was no hope of survival. My 2 IC Captain Qureshi (Shaheed) from Sialkot, was following me when I fell to the ground after the mine blasted, downward.

The next day we were picked up from there by helicopter, and when we came to CMH Jessore, Captain Qureshi was operated first, but he embraced shahadat. He is buried there. For 18 days, I didn’t regain my senses and after 18 days I opened my eyes and my hand was on the sacrificial goat brought by Sobedar Major (SM).

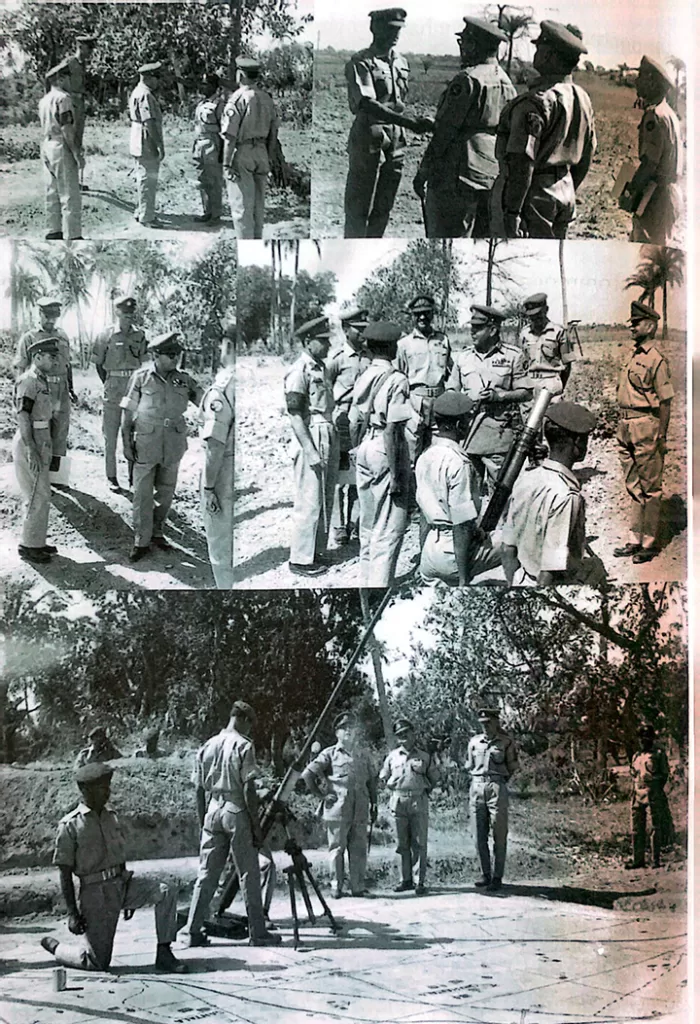

Jessore 1966: with Gen Yahya in the Training Area of 1E Bengal

Then I was evacuated via Sri Lanka and came back as a lung patient to Karachi and then Karachi to Rawalpindi. And then the war started, I requested the Military Secretary (MS) of GHQ and said, I don’t want to die in the hospital, I can wear the uniform, I can walk, my unit has come to Peshawar and I want to join my unit. I was a Major in those days. So, GHQ allowed me and I immediately took a vehicle and joined my unit in the concentration area, Peshawar.

So, when the war started from this side and I was not in uniform, I was commanding the same company. I was one of the unluckiest soldiers in the world, I don’t think there is any example in the military history where you trained the battalion for 10 years and then you have to fight them. I got my Sitar-e-Jurrat by attacking 1st Bengal with the new Battalion where I was posted.

During the fight when I was attacking my old battalion, a man appeared from a bush nearby, aiming his gun at me. I said fire, you won’t get a better target than this one. He threw his weapon away, raised his hand and he said no, I can’t. Then a soldier from my new Battalion jumped on him to kill him, I said no, give him that loaded rifle and he will walk with me facing the other direction. I made his papers for surrender and sent him to West Pakistan. So, you don’t get an award for fighting your men.

When I visited Bangladesh after 20 years, I was Commandant PMA at that time, they took me to my Battalion 1st Bengal, and it was near Dhaka in 1992. And they had called all those old soldiers, they were sitting with me there and they said they had demanded two hours from you to spend with them. For two hours they all were asking questions, and I was asking them and one of them said, one day we missed a very good target there was a brigadier within our rifle range and we were hiding on the border and he came and visited border he was in our killing range and you were with him so we didn’t fire because we thought that by mistake will hit you. So that was the level of the relationship.

Q. Tell us about your successful operation against the dacoits and your community work in Interior Sindh.

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: When I went to Hyderabad as a GOC in 1992, a case was haunting my mind. I asked myself, if you go to the Brigadier rank in the army, you take privileges, you take salaries. In return, you give your blood. When you become a Major General, you pay back. My first goal in Hyderabad was always to think about how I contribute to doing something for the betterment of the people. My second goal was and my focus was one thing that was, how I can turn anti-army interior Sindh into pro-army. The third objective was how to finish the dacoits. That was comparatively easy for me. I completed that in two months. And the dacoits operations that are being done today, are not in my area of responsibility. My area was from the Coastal Area to Larkana and from the Indian border to Malir. It is called Southern Sindh. No dacoity has been made in that area since then. It has been 32 years today, and all the dacoits are in Ghotki, in upper Sindh and southern Punjab. All the dacoities are in that area. And there is none in the lower Sindh. So why do you think that is? Because in the intelligence operations, we identified and searched for the dacoits. In such an operation, from one cave, which is near the village of the current CM Sindh, I killed 12 head money dacoits.

In India, in 1948-49, agriculture was reformed. Nobody can have more than 12.5 acres of land. We have not reformed it to date. If the head money dacoits are not there, how will the Feudal Lords protect their property? So every Feudal Lord is keeping a dacoit. Right? And why anyone wants to be a dacoit? When I was in Hyderabad, I used to take a thermos full of tea and go to jail for 7 days. I used to sit in the Office of the Superintendent. And I used to interview every dacoit there who were serving their terms there. They used to drink tea with me and talk to me. I used to ask them, what made you a dacoit? In a village, when any poor person had a beautiful wife or daughter, the feudal lords would take them away from their families. So to take revenge, the poor person will become a dacoit. He has no other option because he is illiterate. He will become a slave to the lords. I wanted to know why dacoits are made. So that we should nip the evil in the bud.

I started establishing schools and colleges in Badin. I established them in Thar, Hyderabad, Jamshoro, Sehwan Sharif, Rodi, and Dadu. Dadu was the district having most Dacoits. It was my responsibility. This is how I started. I built a residential school in Sehwan Sharif where 100% of the children would live there. A Minister’s wife had opened a school in a village near Dadu. When I established the school there, she made all the children transfer to my school and said she would bear the expenses of all the students there. There was an army unit (24 FF) there. One day I was talking to one of the officers. One of the officers said, Sir, in your approach there is a dichotomy. I asked, what is that? He said, you are sending us to kill the dacoits and you are doing educational work. This is the responsibility of the provincial government. I told him, you are doing the right thing, and I am also doing the right thing. You are killing today’s dacoits and I am blocking the way of future dacoits. All the dacoits that we killed, we identified their dead bodies and sent them to their families. There was a funeral and a burial in the presence of the police. So that we know that the right dacoit identified by the family has been buried. We picked up their wife and children. We took them to the cantonment. We got a job for the wife in a hospital or a school. We gave free education to the children. We gave free quarters to them to live. Until you solve a problem in its entirety, it will not be solved. There is no solution in parts.

I established a cantonment in Chor when I was the GOC there and I built it in the desert. I did not take a single penny from the army. I did not take a single penny from the government. I built the cantonment in about 350 to 400 acres of land. First of all, I established a school there. The families of the Brigade and the Jawans that I shifted from Malir were also shifted to the already-built quarters there. General Kiyani was the Brigade Commander at that time. When he was building the house of the Brigade Commander, I told him to establish a good building as it was going to be a Flagstaff house and would host the flag of Pakistan.

I also established a picnic spot in the desert there for the Army called “Parchi Ji Veri”. Mr. Ikram Sehgal knows this as he was stationed there in the 1971 War. There was also a British Brigade Headquarters there and their troops were in the Chor area. I made an underground division headquarters there on the mountain peak for the Division Commander and the troops are spread from there to the border. I established city-level facilities there in just 14 days. The American Central Command commander came and put General Gore there. Then our Army Chief, Air Chief, Naval Chief, Chairman, Joint Chief of Staff and General Gore and his staff all stayed in the desert. And they are still there. You can go and see it. And in 14 days the 15 km long road was also built. One step down in those 14 days. So, if I can do all this for Sindh, then what is the fault of Jajja? My wife was also an educationist. Her father was also an educationist. So, when I established Cadet College Jajja, first I established the Al-Noor Welfare Trust. This is the Trust’s work and the Trust did not have money. I established four cantonments in Sindh. Out of them, Rahim Yar Khan, a one brigade-size cantonment was taken out of the city and established on GT Road.

In Jamshoro, there is a brigade-size cantonment. One brigade-size cantonment was attached with Pannu Akil. The Armour Brigade was in Malir. I asked them “What’s the use of sitting in Malir near our operational area”. From Malir it will take three days to bring it to Rahim Yar Khan. Chhor cantonment is the main cantonment with all the facilities like CMH. One of the best CMHs of the Pakistan Army is at Chhor.

Q. Tell us about the establishment of your trust and the financial constraints you face.

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: After doing all this when I retired, there was nothing here in my hometown Jajja. So my cousin Ehsan who is now no more with us, we thought that we should also open a hospital. He said no. Let’s first discuss which disease would be cured at the hospital. He was older than me but I said the biggest disease which has to be cured is called Jahat (Ignorance). So let’s arrange some quality education. Then we decided to make a quality educational complex because this is the area of the old British Army, Jhelum, Pindi, Chakwal, and Mianwali. I said if we want to give the people quality education then we should establish a Cadet College. So this is how we decided to establish our first institution, a cadet college. We didn’t have money for the college. So we established the Al-Noor Welfare Trust.

I don’t take any donations from anyone. Whatever I did in Sindh I didn’t take any donation from Army nor Government nor Provincial Government. I don’t take any donations from anyone because donation in this country makes you dependent. When I established the trust, I didn’t have any money. So I and my cousin both contributed. We first gave 5 lakhs each. Then we gave 5 lakhs again and that is our total donation.

The third donation is of 10 lakhs. It was from a Parsi friend from Karachi. He came here to meet me and said that the donation was his dead father’s money you have to accept. It was Ramadan so I couldn’t help but accept. Otherwise, I accept no donations whatsoever. People came here from America to donate and I said to them to spend the money in America. Arnab Singh came here to visit with his grandson and his daughter. He also wanted to donate, he said I am very rich and live in Silicon Valley, and I can easily cover the money for the establishment of your institution. I denied him also. So here I neither donated nor helped and it took me 15 years to make the trust self-sufficient.

We used to take loans from the bank for the construction. I think that If we make one building at a time, the value of the property increased with time. Right? The first loan we took was on our personal property pledge. At that time, it was a third-party pledge against the property. That way you can take a loan. So ,when the first building was built, the loan was released. This is how we managed our financial constraints.

Q. Sir, how do you manage the balance between administering the institution and your family?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: This is a very good question. I will tell you about an incident involving my family. So when the educational complex project was completed, I brought my wife and children here to show them. It was in 2001. On 1st May 2001, the first entry of students was announced. We came here 10-15 days before that. I told my wife that we were ready and the children would come soon. She started crying. She said to me that she is happy that the children will come, and the activities will start. But I have two reasons to cry.

One is that I sometimes forbade you from this work. May Allah forgive me for it. I did that because I was always waiting for you. Your military life was very busy and we had little time as a family. I thought that after retirement, we would have a good family life but you were busy with this project all the time and now your commitment will be very long. She said, May Allah forgive me. The second reason is that you have made a college for the boys, how will the girls in this area get their education? I said to her we would start working on that soon and we would do it together. So, what I am trying to say is, that this institution has made me closer to my family and they are always with me on this.

Q. Sir, do you have any plans to upgrade this educational complex to a university?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: To be honest, we don’t have a plan to upgrade this educational complex to a university in the near future. I and my administration are focused on the betterment of the already provided facilities and the quality of education for the students. We have acquired enough land to extend the campuses of both boys and girls. So as far as its gradation to a university is concerned, there is no such plan on our mind.

Q. Can you provide examples of successful initiatives you’ve undertaken to improve discipline and character development as a head of the college?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: I take immense pride in the fact that our institution’s students stand out for their exemplary discipline and behaviour when they visit other universities and institutions. My son has completed his Master’s degree in the UK. During his time at Foundation University, he mentioned that students from the Jajja Educational Complex were easily recognizable in class. Intrigued, I inquired about the reason for this distinct recognition, to which he replied, “It’s their manner of speech and their overall behaviour.”

Our primary emphasis lies in instilling human values and providing quality education. Without the acquisition of these human values and the provision of quality education, nothing can be deemed right; everything becomes meaningless. Additionally, we aim to shield this young generation from the potentially harmful impact of technology. Mobile phones, in particular, can be a silent but devastating weapon that pierces our hearts. In our institution, if a boy is found with a mobile phone, he is required to break it himself. As for girls and younger children, their parents sometimes secretly provide phones to their servant staff to pass on to them. During holidays, students would hide and use these phones, leading to the unfortunate dismissal of four of our servants.

Regrettably, I have concluded that parents need as much guidance as their children. Parents should not merely sit at home; they should actively participate and engage with their children.

Q. What qualities do you believe are essential for a leader in your professional and personal life?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: I believe that a leader should possess the quality of uniting the people under his command. I am glad I was able to do that and I owe it to the Uniform (Army) for that. As a nation, our loyalty to this country has not been as strong as it should have been. We are divided into different ethnic groups such as Punjabi, Sindhi, Balochi, and Pashtoon, rather than standing united.

To truly become a nation, we require a leader who transcends these divisions and does not favour any specific caste. We as a nation, need a leader who should be able to unite the whole nation under his leadership. We can see the differences in different provinces like Sindh where the PPP aims to expedite the election process to prevent any significant activities that may make people forget their favour. The influence of the PPP extends to institutions like the PIA, where many employees are affiliated with the party. So, we need a leader who has the qualities and abilities to unite this divided nation, a leader who would be free of this caste-oriented system and who would always put the interest of the country first.

Q. What is your education philosophy, especially for girls and women’s empowerment?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: My only philosophy is to provide quality education to everyone irrespective of their religion, caste, financial status, and position in society. I want to save the young generation from the onslaught of technology. Ethical and moral values are destroyed due to excessive and negative use of technology, and parents need to be educated as well for a better future for their children. I stress learning human values as an educationist – only financial stability is not required for Muslims as Allama Iqbal said,

ہم سمجھتے تھے کہ لائے گی فراغت تعليم

کيا خبر تھی کہ چلا آئے گا الحاد بھی ساتھ

This famous verse of Iqbal means that from his poem we thought education would bring economic freedom, but we did not know that atheism would also come with it.

In our society education is a business. Washed off half of the strength these are for the privileged class. It is for a very narrow margin of population. The beneficiaries are not here, the moment they are free from here they will be sitting in England, Germany and America and they are paying fees to universities. Their thrust of knowledge is zero. Two years ago, my two grandsons went to the UK for higher education. They told me that this year 17000 students came to the UK, these students work there on half wages at night. The only agenda is to earn money without learning.

In the prisons of Saudi Arabia there is 90% of Pakistanis (this brings shame to our homeland). Is that how we are going to earn for the country after having paid lacs of rupees here to agents.? Further on girls’ education, I would only say that someone asked Napoleon, how you could make a strong French nation. He said, “Give me good mothers I’ll give you a good nation.” If you gave education to a boy you gave education to one person but if you give education to a girl you gave education to a family. If my wife was not educated my children would not have been what they are today. Here, we are preparing girls to become future leaders and face the world with confidence.

One of my old students came for a job interview, she said I have done MPhil and now I want to come here as a teacher in the girls’ college. Sir my parents also think this is the best place for girls. I think, for girls, two things are very important, one is their security and the second is facilities. It’s a big responsibility. Having 150 girls living in the hostel here, It’s 100% residential.

When they are away from their home when they are away from kin and their parents, they have to be provided for, they have to be compensated, and they have to be made comfortable. Three, their facilities are much better and they keep it neat and clean. This is what I mean and in the fee structure, I have given every girl a concession of 3000 rupees a month to encourage parents for girls’ education.

Q. How do you ensure that the quality of education and training offered at your cadet college is on par with other institutions, despite the financial constraints faced by the students’ families?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: To ensure the quality of education and training offered at our cadet college remains on par with other institutions, especially given the financial constraints faced by students’ families, we must acknowledge the evolving landscape shaped by social changes. The world outside our gates is rapidly advancing with technological transformations, and it’s our responsibility to safeguard and nurture the potential of our students within these changing tides.

While we may strive for excellence, we cannot isolate ourselves on an island of educational superiority while ignoring the sea of challenges and complexities in the wider world. It’s a continuous effort, a commitment to maintaining an environment where our students are protected and guided, even when they are not under the direct influence of their parents.

We meticulously identify and address any issues that arise, and we often seek parental assurance, both explicit and implied, ensuring that our student’s needs are met, whether it’s in the realm of academics or their general well-being. Each student has a comprehensive record, and we remain deeply involved in their growth and development, sometimes knowing more about them than their parents. This approach is essential to maintain the quality and standards we aim to uphold.

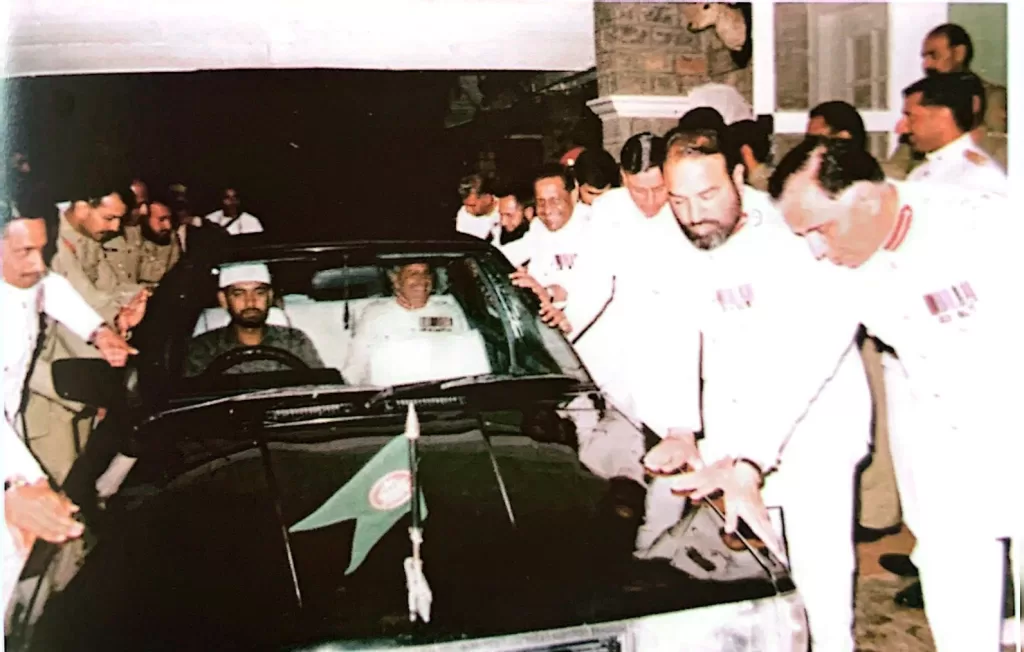

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan With Governor Sindh

Q. Cadet Colleges often have a strong focus on physical fitness and outdoor activities. How will you promote these aspects within the institution?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: Promoting physical fitness and outdoor activities within our institution is an essential component of our broader mission. We believe in nurturing students not only academically but also as responsible citizens. Given the current societal challenges, instilling values, ethics, and basic human rights is of utmost importance. It’s about building well-rounded individuals who can contribute positively to our nation and the world.

In this context, we have a dedicated hockey ground, and I often advise our teachers to observe students there. Watching them engage in sports offers a unique window into their character and behaviour. Sports provide a platform for students to express themselves and reveal their true selves. My primary focus is on holistic education and personality development, where physical fitness and outdoor activities play a pivotal role.

Q. Can you highlight some success stories or notable achievements of students who have benefited from the free education and training provided by the cadet college?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: I will tell you that some students came from UK, America, and France to study here. A student came from Dera Bugti his name was Rehman his father even didn’t know how to sit on a chair. Now that Rehman is a Doctor in Quetta. He had an issue with his eyesight that’s why he was unable to join the army. Nowadays he is planning to go abroad to specialize and because of him, another boy has joined us from Dera Bugti.

I feel affection for every student here, and a girl’s story touched my heart. One day General came from GHQ for the verification (he came once a year). They gave the NOC to this cadet College. I took him to the Girls’ College he was asking the girls what they wanted to become, and a small girl was standing in the front she said, “Like you, we want to be officers in the army.” There was a girl from Sargodha who stood and said, “Sir, not simple officers, we want to be SSG officers.” That thought was born in her mind there. Recently, that girl came here again for someone’s admission and met me. I asked her if she had joined the army. She started crying, the principal was also there she put her hand on his head. She said, Sir after FSC when I went back home, I had my dreams but my parents married me within six months. I felt the pain and sorrow of that young enthusiastic girl, still now her dreams made her cry – her pain is for a lifetime.

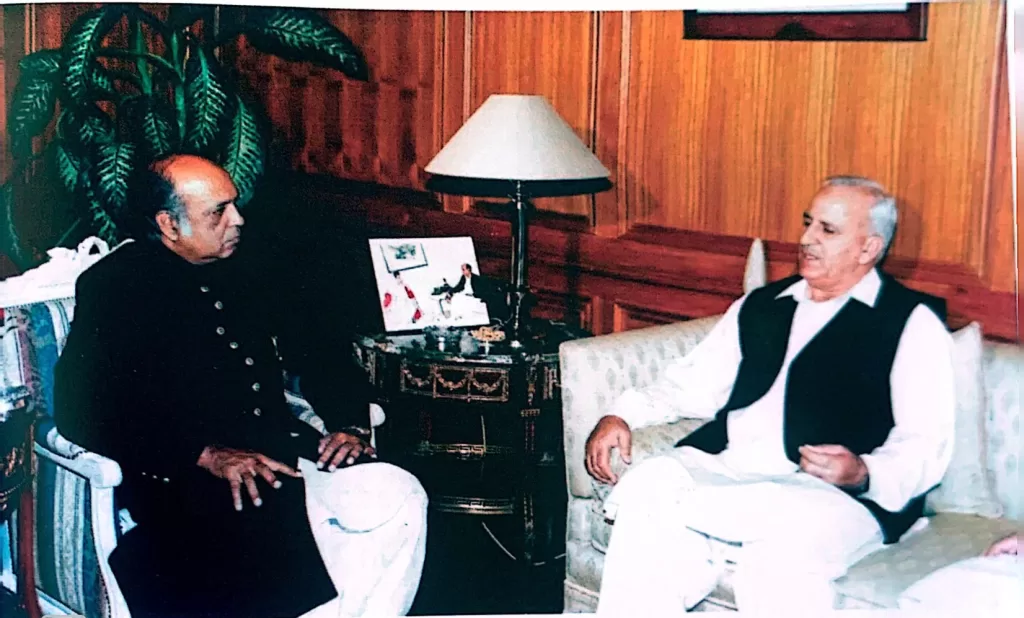

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan With Lt Gen Hamid Gul (late)

Q. What do you see the future of this college?

Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan: Looking ahead, I envision a bright future for this college. I aim to shape both of these institutions into role models that others can emulate. The continuous improvement of these colleges is a priority. To accommodate this vision, I have procured additional land spanning 30-40 kanals, some of which are already being utilized for facilities like a football ground and a cafeteria for the girls’ section. This land can also be earmarked for future expansion if the need arises. I must note that a government degree college was established 1 kilometre away from our location, which has led to local students enrolling there. However, our focus remains on maintaining the quality of education that this institution is known for. To provide a conducive and comfortable living and learning environment, we are considering additional amenities such as a swimming pool and riding facilities. To facilitate these plans, we have acquired 80 kanals of land in total, even when land prices have significantly appreciated. This area now comprises residential quarters for teachers and the principal, each with its own sports facilities.

One challenge we face is the financial aspect, as we do not accept donations from external sources or the government. Yet, our commitment to ensuring access to quality education remains unwavering. My family and I sponsor the education of underprivileged children, covering their fees, books, uniforms, and other necessities. We are dedicated to providing a nurturing educational environment that empowers students and contributes positively to society.

The life and experiences of Lt Gen Lehrasab Khan serve as a testament to the dedication and valour that define the unsung heroes of our world. His remarkable journey, from humble beginnings in Jajja to the battlefields of the wars, showcases the resilience and commitment that have earned him a place in history. Moreover, his post-retirement efforts to provide quality education and shape the future leaders of Pakistan are a testament to his enduring passion for service. His story is a source of inspiration, reminding us of the determined spirit that can shape destinies and leave a lasting legacy.