The Account of 1965 War As Fought and seen from the Airborne Eyes key to our success. It envisaged cutting off the tenuous line of communications of the Indian defenses along the Ceasefire Line at Akhnur. Once this was done, however, how could the expected outcome have been expected to be anything other than all-out war? How the highest ranked commanders in the Pakistan Army concluded that the war would not flare up towards international borders and remain in Azad Kashmir is beyond me. I witnessed the entire buildup of sequences and the final flaring up of the war.

There are many self-aggrandized accounts which have been circulated in the Country, catching the attention of many people. Nowadays, I hear some of these intellectuals claiming that the Pakistani Military had been defeated in all wars it has fought, and it is precisely that narrative which I want to challenge. Nothing could be further from the truth. Hence these memoirs of mine were motivated to put the record right.

I have read several accounts of the 1965 War. The range of reports encompasses the rendition of war as was perceived through the eyes of the Indians, Pakistanis and the foreign authors. Every description had its own particular ideologically informed version of events. The most comprehensive account I found in the study carried out by the Directing Staff and the students of Command and Staff College, Quetta spread over some years. This has now been compiled as a book called the “History of Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 “by Lieutenant General (Retd) Mahmud Ahmed. It is based on the War Diaries written by soldiers from different units, and interviews and briefings.

The book attempts to do a comprehensive study and comparative analysis between the account that he compiled and the official version of events as seen in India. The book suffers from being written by someone who did not experience the events himself, and it remains rather limited. A better example of an account of the War that I believe is on par with reality would be the book, “Men of Steel.” It is based on the dispatches of Major General Abrar Hussain, one who was in the battle’s thick and thus had the benefit of firsthand experience and knowledge.

The account lists the details of the battles in chronological order, but I feel that although it alludes to some confusion and brazen blunders committed, it does not go into detail; more so, it does not truly capture the spirit of the troops fighting on the ground. These aspects need to be elicited in some depth and given projection so that the facts stem out in their correct perspective and in actual truth. We must give credit where it is due and highlight all the mistakes made. It is with these feelings I embark on my humble effort, to portray the picture of the battlefield as accurately as I could perceive, read and transmit. I was privileged to have watched the operations closely and being fortunate enough to have close contacts on the ground in the right areas. I had seen the operations mostly in the role of airborne eyes. It provided as graphic a picture of the details as on a sand model. Since I operated only in Chamb and Sialkot Sector, my rendition will be focused more on these operations, but I will try to make informed judgments on the operations carried out in the other Sectors.

Before recording the historical events of the 1965 War and the role played by the Army Aviation to support it, we should pause and reflect on the role assigned to the Army Aviation. When we changed the traditional Air OP role to embrace the overall concept of Army Aviation role in 1959, it was a big quantum jump. From purely the simple purpose of adjusting Arty Fire as Air OP, Army Aviation was embarking on a resolute mission as a full-fledged Combat Arm of the Army. The different teachings and definitions of the role of Army Aviation can best be defined and summarized under the following parameters:-

- Battlefield Surveillance

- Command and Control

- Mobility

- Fire Power

- Adjustment of Artillery Fire

- Casualty Evacuation

Army Aviation in Pakistan was still in its infancy in 1965. It was in transition. The capability for any physical mobility to act as a force multiplier did not exist. The only mobility that it could provide was to enhance the mental ability of the field commanders to take quick and timely decisions. This is a very vital factor. Getting a bird’s-eye view of the battlefields would help maintain the flow of accurate information back to Higher Formations. It would go a long way in clearing the customary fog of war. The Army Aviation had no integral firepower capability. The entire role that it played has to be tested in the concepts enunciated and recorded in that context.

Soon after I took over the Squadron, trouble brewed in Rann of Kutch. This dispute was centering on the region of the former Province of Sindh (India) and Kutch (India). The area is mostly waste marshy lands. Even the dispute dates back to 1843. Before partition, three attempts were made to settle this dispute. The details are as follows:

First Attempt:- The first attempt was made in 1908 when the Kutch Government wanted to bring the entire area under their exclusive control. To this, the Sindh Government objected. Some meetings were held, but the question remained undecided due to the death of Mukhtar of Rann of Kutch.

Second Attempt:- This time the matter was referred to a commission in 1908. It resulted in a kind of compromise, under which the Sindh Government agreed to surrender half of the area to Kutch. About the remaining half, no rational decisions were taken as to the boundaries, and the area thus remained unmarked. This gave rise to various administrative difficulties, particularly in the border regions, where no effective control could be maintained. This led to many incidents like harboring of dangerous characters by the opposing sides, lifting of cattle and other animals, the police and the revenue authorities clashing over their jurisdictions and many other such like disputes.

Third Attempt:- The Government of India finally intervened in 1938, and a survey party was sent to demarcate Sind-Kutch boundaries. The Mukhtar of Kutch accepted the claim of Mukhtar of Sindh, to the half of the territory. This became unfructuous as the authorities of Kutch later backed out and refused to accept the decision.

Thus, this dispute was inherited by the Government of Pakistan at the time of partition. Sindh Government maintained its claim over half of the area. After partition, India developed a Naval Base at Kandla North of Kutch. They also planned to link this base, with Rajasthan and Central India, by Railway line via Deesa. This Railway line was to pass through the Rann of Kutch. When Pakistan realized the strategic importance of this move, they took up the matter with the Government of India. While this dispute was the subject of correspondence between the two Governments, the Indian forces occupied Chad Bet on February 24/25, 1956. This was hitherto, historically, under the control of Sindh Government. Our Border Police withdrew to Wingi and the whole of the area, Rann of Kutch, came under the control of India. The Noon-Nehru agreement in 1958 and the Sheikh-Swaran Singh meeting held from January 4 to January 11, 1960, could not resolve the matter. Both sides continued studying the relevant material. While this status quo was being maintained, the Indians built up their troop concentrations in the area since January 1965. There were air violations of the area by the Indian Air Force, from February 1965. At this stage Air Marshal M. Asghar Khan, Commander-in-Chief, Pakistan Air Force, called his counterpart in India. This had an immediate effect, and the violations stopped.

On March 27/28, 1965, the Indians carried a major joint exercise with Combined Army/Naval compliments called “Arrow Head.” Due to all these moves, Pakistan also retaliated and concentrated its troops in the area. 8 Division, under the command of Major General Tikka Khan, was moved to the area. GOC Maharashtra and Gujarat region, Major General P.C. Gupta, MC, had earlier assumed the command of the Indian troops in the area. He had already undertaken some preliminary operations. Army Aviation saw its initial battlefield baptism in Rann of Kutch. One flight of No.1 Army Aviation Squadron remained deployed there from the middle of April 1965 to May 6, 1965.

On arrival at Badin, the pilots immediately started their familiarization of the area of operations. The customs track, Biar Bhet and the entire control line of the un-demarcated international boundary, was extensively flown over. The navigation in the area was terrible. It was all flat with many sand dunes, which too were drifting because of the wind effect. To provide close support to the advancing troops, two advanced landing grounds were established at Diplo and Ali Bunder. The flight was based at Badin, but during the day it operated from forward strips.

Regular recce missions were undertaken soon after the arrival. Liaison was also maintained with HQ 8 Division, Commanded by Major General Tikka Khan, and the other formations and units. Major S.M.A Tirmizi, brought an Hx13 helicopter and joined the flight. GOC 8 Division used the helicopter extensively. Every day, he flew out regularly to visit the troops. He used this helicopter to carry ice, fruit and other essential elements to the forward troops. It was a slight gesture but was well appreciated by the soldiers in those hot and humid conditions.

Some minor skirmishes had already taken place. The major operation carried out was the attack at Biar Bhet position. In the earlier attacks on April 9, 1965, 51 Infantry Brigade had captured Ding and Sardar Post. I too visited that area and saw this operation and meet with the Commanders and troops on the ground.

On April 26, 1965, 6 Brigade under the command of Brigadier (Later Major General) Iftikhar Janjua was ordered to attack and capture Biar Bhet. 2 FF Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel (later General) Iqbal Ahmed led the attack. The Brigade Commander was right behind the attacking infantry battalion. The attack was supported by Artillery fire, and the Army Aviators successfully and efficiently undertook the artillery shoots. The Indians abandoned the positions, leaving behind a lot of equipment and ammunition. During the adjustment of the artillery fire by Army Aviators, a big Indian ammunition depot at Dharamsala was blown up. It was never clear as to whether the depot went off accidentally or because of artillery fire adjustment by Army Aviators. At night a strange panic gripped the infantry positions at Biar Bhet. A convoy of 10-15 vehicles with their full lights was approaching the position from the direction of the enemy. Own troops considered these to be enemy tanks and were utterly baffled. They considered these to be some strange new tactics by the enemy. Our own troops opened up with all their weapons, including the Recoilless Rifles. The artillery observer, Major Riaz-ul-Haq Malik called for artillery fire. This game went on the entire night. Neither the enemy vehicles were advancing forward towards our positions, nor were our own troops making any move to venture the unraveling of this mystery. The stalemate prevailed, and both sides did not carry out any probing and attempting to resolve this dilemma during the night. At dawn, it was revealed that these vehicles were part of a convoy. These vehicles were 3 Ton Muktiman and were carrying rations and supplies and had lost their way during the night. The drivers and the other crews had hidden underneath the vehicles the whole night. They did not venture to run back to make their escape and were all captured the next morning.

Since there was no enemy air force operating in the area, the L-19’s were flying at an altitude of 3000-5000 feet. This provided a very broad coverage of the area and gave the Army Aviators an excellent overview. Army Aviation flew regular missions; carrying out adjustment of Artillery Fire, liaison with the formations and reconnaissance of the entire area of operations.

They made some emergency evacuations too, through alternative arrangements of accommodating stretchers in the L-19 Aircraft. Lieutenant Colonel Naseerullah Khan Babar, Commanding Officer 3 Army Aviation Squadron, also came in the area and volunteered to fly as the helicopter pilot. During my visit, I was accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel (Later Lieutenant General) Saeed Qadir, who was commanding the 199 Engineering Battalion at Dhamial, which provided the entire maintenance support to all the Aviation units. GOC 8 Division, the staff and the other unit/formation commanders were all full of praise for the support being rendered by Army Aviation. Special Services Group was also assisted in their recce for any launching in the area.

On the return flight from Badin, I encountered awful weather. On landing at Sargodha, when I received the Met briefing, I was informed not to proceed further. Considering that it was important to get back to base, I flew out from Sargodha to Dhamial. Accompanying me was Maj. K.S. Ghalib in another L-19, and Lieutenant Colonel Saeed Qadir was sitting on the rear seat in the L-19 being flown by me. With great difficulty, the salt range was crossed. It was raining very heavily, and the cloud base was very low. After clearing the salt range, the flight to Dhamial had to be undertaken at low attitude to keep the close visual contact with the ground.

The familiarity of the area, being the local flying area of Dhamial base, helped. With great difficulty, the two aircraft reached the Sowan River. As we reached closer to the Dhamial Base, a sense of relief was setting in, but torrential rainfall proved that luck was not on our side. The intense rain made a thick wall of pouring water with no forward or downward visibility. The aircraft with great difficulty took a blind turn back. I had already briefed Ghalib, who was following me, to turn back immediately as soon as he sees me start a turn. As I emerged safely out of the thick and blinding rain, I saw Ghalib’s aircraft ahead of me. I was relieved. There were other close calls in my Aviation career, but this was the closest to having a fatal accident.

Dhamial base, which was so close, still proved to be too far. The aircraft flew back to Chakwal. The parking and the security arrangements were made. We took to the comfort of the hospitality of Attock Oil Refinery Camp at Balkassar. We stayed the night with Masud, a golfer friend. He was a keen golfer and was well known to his unexpected guests. Through the communication links of the Attock Oil Refinery, messages were sent to Dhamial Base and the families of these officers, informing them that the aircraft had safely landed at Chakwal. This put at rest all the panic that was gripping Dhamial Base because of these missing aircraft.

After performing regular missions of recce, liaison, Command and Control and some casualty evacuations, the flight of L-19 aircraft and the Hx13 helicopter returned to Dhamial on May 6, 1965. As the main strike force of the army, 7 Division and 1 Armoured Division had been placed together. Lieutenant General Altaf Qadir was the Force Commander. As narrated earlier, he had prepared three original plans. GHQ had to decide on the final option as the time and opportunity arose.

When “Operation Gibraltar” was launched, the tensions mounted. In anticipation that this may flare up into an all-out war, 7 Division was moved from Peshawar to the area of Balloki. At this stage, 1 Army Aviation Squadron, that I was commanding, was placed under Command 7 Division. When we moved into the area, we made our strip on the left bank of Balloki Canal, just short of the bridge on the main GT Road and camped in the mango archives of Sardar Ahmad Ali, father-in-law of Sardar Asif Hayat Khan. When I reported to GOC Altaf Qadir, he was jubilant to receive me. I was told that 1 Armoured Division had been placed under his command and our operational plans would be on the lines and out of the different choices that had been planned earlier at Peshawar. Since I was familiar with those, he would call me for some operational briefings that he was holding for Major General Nasir, GOC 1 Armoured Division. I had known him. It was not a pleasant interlude with him. I have already narrated the details of my experience of serving under his Command at Kharian. What was coming to my mind now was my astonishment why this man of such pitiable incompetence was still in Command of this most important formation of the Army?

It was under these depressed thought of my views and assessment of the capability of Major General Nasir, that I was attending the briefings being carried out by Lieutenant General Altaf Qadir. Painstakingly, and with thorough details he was briefing him on these plans and to the surprise of us attending those, Major General Nasir was hardly paying any attention and would even go to sleep. This really shocked Lieutenant General Altaf Qadir. In utter exasperation he exclaimed, “Look at him. He seems to be least interested. He has even gone to sleep!” Seeing his total lack of interest and utter apathy in shouldering his responsibilities, Lieutenant General Altaf Qadir called General Musa the next day and told him in no uncertain words that Major General Nasir must be removed from his Command immediately. To the horror and surprise of all of us, the answer came as transfer of Lieutenant General Altaf, Qadir to CENTO and the posting of Major General M. Yahya Khan as the new Commander 7 Division.

On seeing the orders, Altaf Qadir broke down and with tears in his eyes, he was emphasizing, “I have trained this formation and am desperate to lead it in battle.”” But who cared! Even later, when the hostilities were about to start, Lieutenant General Altaf Qadir rushed back to Pakistan from Ankara and pleaded that he be given command of his old formation. It was refused, and this Army went into war with the main strike force broken up and a man of the caliber of Major General Nasir still entrusted with the Command of 1 Armoured Division. Lieutenant General Gul Hassan in his “Memoirs” also opinionated in some details the history of the sordid tale in which this most important formation of Pakistan was handled. He starts off by describing, “The tale of the Armored Division was decidedly heart-rending. It was our elite formation and by far the most powerful in the Pakistan Army.” He then narrates how from the beginning Infantry Officers were inflicted upon it.

Next he comes to the Command of Major General Nasir Ahmad Khan, again a non-armor officer, and opines, “He was a timid person by nature and remained aloof. How he was selected to command our premier formation is baffling”. He surmises, “General Nasir sought refuge from the innumerable complexes he suffered from, including professional insufficiency, by barricading himself behind mountains of courts of inquiries, explanations, and other such contrivances, merely to keep everyone on the hop while he sat securely in his warm seat, supposedly mastering the art of armoured warfare. He was destined to be in Command of Armored Division in the 1965 War.” This is in complete conformity of my opinion of him as expressed earlier. The question is as to why he would be in Command? Of course General Musa was guilty of this criminal act, but it was also obligatory on Brigadier Gul Hassan, the DMO with his armour background, to impress upon General Musa of this folly and to plead with him to remove Major General Nasir from this key Command. He has to share the blame for the fiasco.

The breakup of the main strike force is another very sordid chapter in our history. As the tensions were building up, Army had made a request for the raising of two more Infantry Divisions and forming up of another Corps Headquarter to co-ordinate the thrust of the main strike force. It was declined, and we were told that the Finance Minister had refused to provide for the funds needed. One was inclined to wonder who was in charge, at one end General Ayub Khan who was taking the country to war or his Finance Minister who was there to sabotage his efforts! The fiasco at the launch of the 1 Armoured Division at Khem Karan, on September 8, 1965, could have been easily foreseen and averted. I will cover this later. The Squadron moved back to Dhamial by the end of June 1965 and kept waiting in the wings there.

The battlefield test arrived on August 29, 1965. I was called by the Base Commander, Colonel A.B Awan, who asked me to report to General Officer Commanding 7 Division, at Jalalpur, near Gujrat. The move was scheduled for August 30, 1965. I moved to Jalalpur, taking a small group with me, while the rest of the squadron was located at the Gujrat Airfield. In a meeting with GOC 7 Division, Major General A.M. Yahya Khan, I was informed that 7 Division Headquarters had been moved to this sector with a particular mission. On September 1, 1965, 12 Division was to launch their attack across the line of control towards Chamb. PhaseI of the plan was to secure the line of River Munawar Tawi and was followed by Phase – II, which was the capture of Akhnur. Major General Yahya further told me he along with the HQ 7 Division had been ordered to move into this area, to be prepared to take over the command of the operations in the Chamb-Jaurian Sector later. He was only waiting for an order from the GHQ, which had not yet decided when this would be done.

This is just a prelude to the Army Aviation earning its battlefield spurs. The Army Aviation had already overseen limited operations in the Northern Areas under 12 Division jurisdictions; casualty evacuations, facilitating Command and Control were the missions being performed. But the drums of war had begun to beat louder. The Indians started carrying out limited offensive operations across the Line of Control in retaliation to Operation “Gibraltar” being conducted by the Mujahideen in occupied Kashmir. These Indian counter operations were reaching dangerous proportions. They had to be neutralised. To counter this Operation “Grand Slam” was dovetailed with “Operation Gibraltar.” Hence a decision had been taken to exercise the option of launching a major operation across the Line of Control at Chamb.

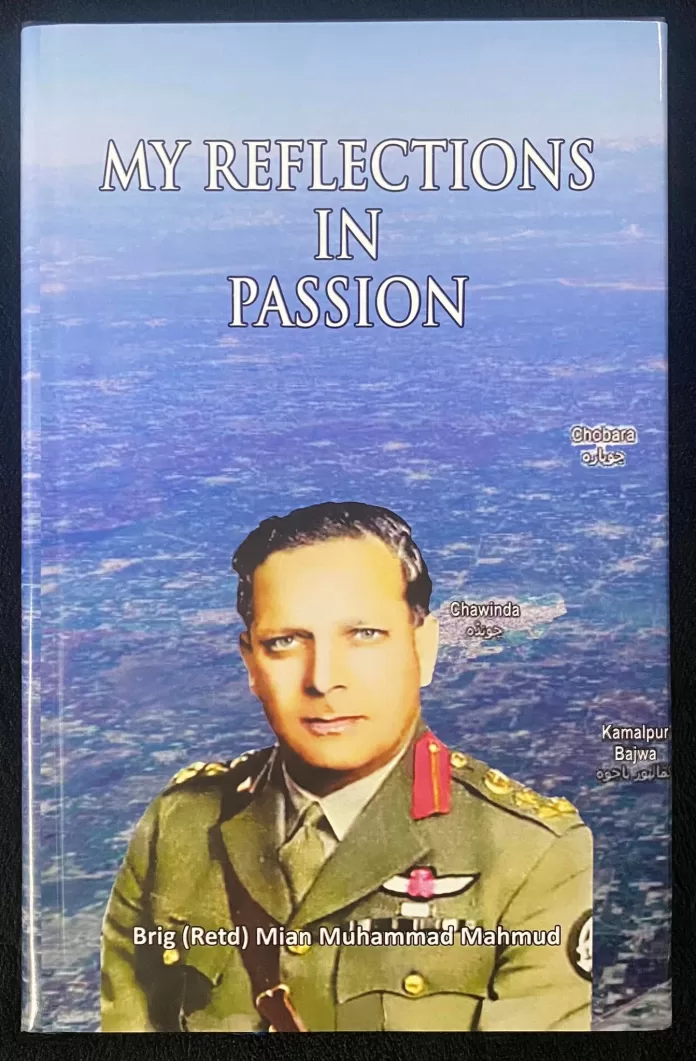

Coming to the account of 1965 War and testing the role of Army Aviation in its performance; needs correct military perspective and background. This can be best described in tandem to the operations on the ground and specific description of the performance by the Army Aviation in support of these. Army Aviation at this stage comprised Base HQ and three Aviation Squadrons, comprising 1, 2 and 3 Army Aviation Squadrons. The entire Army Aviation had an integrated maintenance and logistic support comprising the 199 Aviation EME Battalion and an Ordnance Depot. The base was being commanded by Colonel Azmat Bakhsh Awan, the senior most pilot. The squadrons 1, 2, and 3 were led by Lieutenant Colonel Mian Muhammad Mahmud, Lieutenant Colonel Muhammad Khan and Lieutenant Colonel Naseerullah Khan Babar, respectively. Number | and Number 2 Squadrons were equipped with the L-19 aircraft and Number 3 Squadron, which was raised in 1964, had the latest H x 13 helicopters. Army Aviation at this stage was entirely unarmed and started the 1965 War under these limited capabilities. The battlefield spurs that the Army Aviation won were in these modest conditions. Undaunted, full of devotion, these dedicated officers, who represented a happy blend of professional soldiers and technocrats as pilots, integrated themselves with the ground troops with ease and full understanding of each other.

On September 1, 1965, when at 0300 hours with the firing of guns and the launching of the ground offensive at 0500 hours, operations in Chamb rolled off; the Army Aviation had fully assumed its place in the battle alongside with the field troops. They positioned themselves within one day of their arrival in the area. The transition of the squadron to form a complementary team with Headquarter 7 Division went smoothly and took relatively less time since I was thoroughly familiar with all the staff and commanders at the Division Headquarters. This union proved to very cohesive and paved the way for excellent teamwork. The events of the war as they unfold themselves will provide sufficient credence to this statement. A flight of 2 Army Aviation Squadron had earlier moved to Bhimber, and upon my arrival in the area, I assumed command. Throughout the Chamb operations, I carried out all the planning and coordination of the entire Army Aviation effort in the area. The flight under Major Rabbani had been already assigned to support 12 Division and had integrated itself into the operational plans of 12 Division. As the tanks and the infantry rolled out of their positions from the Forming up Point (FUP) area on September 1, 1965, at 0500 hours, the Army Aviation was there alongside with them.

The map of the area and the dispositions of own and enemy troops is attached as Annexure-1*. The plan of attack for 12 Division had been prepared by Major General Akhtar Malik and is attached as Annexure2*. There were no written orders; all orders were given out verbally. It was a two-pronged assault; in the North, 4 AK Brigade under Brigadier Hameed, attacked with 5 & 19 AK Battalions, with the 8 AK Battalion acting as reserve. An ad hoc armour squadron was under command. Its objective, under Phase-I, was the elimination of enemy troops West of Tawi, and in the Laleal, Dewa, Sakrana, and Chamb sectors. In the South, the 102 Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Zafar Ali Khan, was tasked under Phase I to capture area west of Tawi, including MandialaUllan Wali, Pir Jama. The Brigade attacked with 11 Cavalry, followed by 9 and 13 Punjab. It was tasked to capture Chak Nawan-Chak Pundit by 0900 hours on the 1st of September.

Phase-II was the capture of Chamb-Sarkana by 9 Punjab supported by 11 Cavalry by 1200 Hrs on the 1st of September. Attacks from both directions mostly proceeded on time, but some sporadic resistance from the enemy led to delays, which was caused by enemy positions and pockets at different places, and efficient fire of their recoilless rifles took a toll on our tanks. The terrain posed some problem to armour and slowed the advance of 11 Cavalry initially, however, that did not stop their progress. The tanks, the infantry and the ground observers kept dealing with the resistance very effectively. The role of Army Aviation remained rather limited. Major General Akhtar Malik was leading the attack himself, staying close to the frontline troops and perhaps purposely was not in communication, even with his Tactical Headquarters. The undulating ground provided reasonably good observation in the area, and the airborne eyes were not required to supplement that.

The evening of the 1st of September saw some excitement for the Army Aviators; some L-19 aircraft and Hx13 helicopters had been flying in the area to carry out the surveillance of the battlefield. The customary fog of war was ever present. The Army Aviation was active but did not perceive any clear picture of the battlefield. Suddenly there was a buzz of excitement. At about 1600 Hrs, four enemy aircraft suddenly appeared, starting an attack on our ground troops. As these aircraft dived in their attack runs, our PAF fighter aircraft majestically could pick them and were in pursuit. Within a brief span of time, all four Indian aircraft were shot down. The interception of these planes was at such a low altitude that none of the enemy pilots could bail out and were all killed. Air Marshal Nur Khan, the Commander-in-Chief of Pakistan Air Force, who was flying in an L-19 aircraft, Lieutenant Colonel N.U.K. Babar and I, who were flying in Hx13 helicopters, witnessed this thrilling encounter. I, along with Captain Askree, the captain of the helicopter, landed at one sight of the crashed aircraft and picked up a piece from the wreckage. It was the insignia of the Indian Air Force, which I later kept as a war trophy.

Just as the excitement was dying out, Lieutenant Colonel N.K.Babar, who had been milling around in the area in an HX13, inflicted upon himself a unique and an unparalleled encounter. It was getting to be the evening of September 1, and our troops had approached Chamb. In the process of their advance, they had by passed some Indian positions on their way, where the enemy forces were raising white flags as a gesture of their intention to surrender. The 13 Lancers and 6 FF had bypassed Pour picket, where they encountered this incident, but as they were progressing to Chamb, they could not spare any effort or time to round them up. Lieutenant Colonel N.K. Babar, Major A.L. Awan, and Captain Akram were surveilling the area on board a helicopter when they saw these white flags. What happened next is best described by Babar himself in an account that he wrote. Was it initially an act of bravery to land the helicopter near this enemy position, or was it stupidity? Did this later lead to a unique manifestation of courage? Let the readers form their own opinion!

3rd Army Aviation Squadron (Rotary Wing) had been directed to provide a helicopter for the transportation of Brigadier Ishaq (Brigade Commander at Rawalakot), from Murree to Rawalakot on September 1, 1965. It was conventional to dispatch two helicopters on missions in Azad Kashmir. In the first helicopter were Lieutenant Colonel (Later Major General) Naseerullah Babar and the 2 I/C Major (Later Lieutenant Colonel) Abdul Latif Awan. The second helicopter had Captain (Later Colonel) Late Mohammad Akram and one other pilot. On arrival at Murree, it was disclosed to us that the Pakistan Army had launched an offensive operation in area Chamb and that the principal elements (11 Cavalry) were in the town’s vicinity of Chamb. The helicopters took off, and on landing at Rawalakot, the news remained the same.

After having finished their work, a suggestion was made to Brigadier Ishaq, that they may proceed to the area to witness this advance towards Chamb. Brigadier Ishaq, already having been wanting an opportunity to meet his Commander General Akhtar Ali Malik, readily agreed to this suggestion. Resultantly, we left for Chamb via Bhimber (HQ 4 Sector) to get the latest information on the prevailing overall situation. At Bhimber, the information remained the same. After partaking in a quick lunch, we left and landed in the gun position, in Padhar Nullah. Since we neither had maps nor were familiar with the area, it was found out the general direction of Chamb from the GPO. At this stage, Brigadier Ishaq went back to Murree as he had scheduled a meeting in the evening.

In the other helicopter, Major Awan, Captain Akram, and I took off and proceeded towards the indicated direction. En route, we located an enemy post, which had not been attacked and was on a flank and in considerable depth. When overhead, I asked Major Awan to land so we could pick up a couple of weapons as souvenirs. Major Awan suggested that we involve in the venture on the return journey. Thus we proceeded further, but could not locate a suitable HQ or a Command vehicle, and in consequence, Major Awan suggested that we return as it was getting late in the afternoon. As we turned back, we learnt on the ARC-44 that Brigadier (Later Lieutenant General) Hamid Khan had been ambushed. We asked them to relay any information of the position so we could fly there and retrieve Brigadier Hamid. While we were engaged in this conversation, we again arrived at the same enemy position, and I asked Major Awan to land. He mentioned something about there being people in the post, but being preoccupied with the ARC-44, I did not understand the implications. As the helicopter touched down, I jumped out, and with the only weapon I had (the flying cap akin to the current golf cap), asked the men to stand up. It was then that we realised that we were amid a significant number of enemy soldiers (later it transpired that it was a company post of 5th Sikh Light Infantry and as customary in the Indian Battalions; they had Mortars, Recoilless Rifles, and Light Machine Gun elements from a Rajput Battalion.

Still influenced by the desire for war souvenirs, I asked Major Awan to land near the main bunker, while I got a couple of weapons from the check post and then we would take off in the helicopter. Major Awan, to his credit, convinced me that there might be a minefield around the post so I called out to a Sikh soldier to come over and on my finding out, he confirmed that there were mines along the barbed wire. I asked him to lead the way into the post. As I walked in, Awan brought over the helicopter and landed near the central bunker. On inquiry, I was informed that they had been subjected to some shelling and there were a few wounded lying inside. I moved into the bunker, and after assessment of the bodies, I found that there were a couple dead and another couple who had been injured. The Company Commander, Major Negi had left the post on the plea he was proceeding to fetch some rations, and in his absence, a subedar was in charge of the post. On emerging from the bunker, I saw two enemy aircraft approaching from the South, possibly having seen the helicopter.

I immediately rushed towards the chopper and indicated to Major Awan about the potential of an impending air attack. The Indian aircraft made a pass over but did not open fire, then turned around to make the next pass as to attack the helicopter/position. Our helicopter had in the meantime taken off. I ordered the men to go to the ground as the planes were approaching again. However, before they could attack the post, they were hit by one F-86 Sabre and crashed ahead of the position. I directed the men to place their rifles on the parapet and move out. After having moved them out, I asked the Senior JCO to sort them into ranks. Realising that the primary aim i.e. getting souvenirs had been overlooked, I asked one of the OR’s, to go into the position and fetch two rifles (brand new GIIs). Noting that the Rajputs (Heavy Weapons Troops) seemed a little sullen and may react adversely, they were at the head of the column, and the march towards the lines of Pakistan was started. After about three miles, I met (Late) Major (Later Major General) Abdullah Saeed, who was moving forward with his battalion.

I requested that he take over the prisoners, but he refused, showing that his troops were moving forward towards Chamb. This march continued, and at dusk, we arrived at the Moel post (total distance about 7 miles). Here we stopped for tea, and anxious about the helicopter, | made inquiries and was informed that it had safely reached Kharian. After tea, the march started again towards Padhar (The location of Brigade Headquarters) about 3-4 miles away. It was dark, but the full moon made movement possible. At about 2000 hrs we reached the Brigade HQ at Padhar (now taken over by the HQ Corps Arty). I left the prisoners in the volleyball ground as we proceeded to the Officer’s Mess, where I met the (now late) Brigadier Amjad Chaudhary and his staff, and informed them about the men. They were in great disbelief, and they came over to see the Indian troops (around 75-78) sitting on the ground.

I once again made a request for vehicles to move the prisoners to Bhimber, but it was turned down because the Corps Arty was being redeployed and consequently no vehicles were available. However, I was informed that some bridging equipment had been moved to Tawi and on its return, vehicles would be available. At around 2 AM the vehicles arrived, and I directed the men to show me their battalion embussing drill, and they complied with efficiency. At around 4 AM we reached the Sector HQ at Bhimber where I handed over the men and went off to sleep. At around 10 AM the next day, a helicopter arrived and brought me back to Dhamial where (now late) Colonel (Later Lieutenant General) A.B. Awan received us and counselled me against my recklessness. I presented one rifle that I had taken to the Army Aviation Mess and kept the other for myself. The OR’s when interrogated by the Intelligence narrated the events.

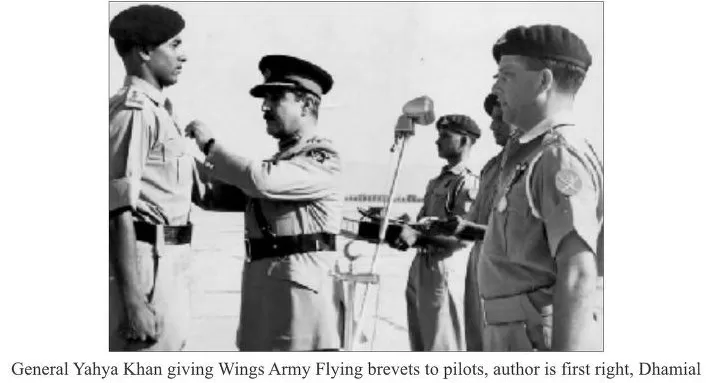

Later that evening at the President’s Press Conference, the Director General of the ISI Brigadier Riaz brought the event to President’s attention, suggesting that this news be released to the Press which could also help raise the morale amongst the troops. Since I had contacted no one in person; different reports of the incident were published in the Press, some showing that it was a PAF helicopter. Subsequently, in recognition of this act, I was awarded the Sitara-e-Jurat. It later transpired that the position was a Company post (PAUR) and as nature works in its mysterious way, I was given another award of Sitara-e-Juraat (within 100 yards of the area) in the 1971 war. At that time I was commanding 111 Brigade”. When I learned about this episode, I was bemused. But later, when I met Bob, my spontaneous remarks were, “It was initially an act of stupidity, but it eventually turned out to be one of great personal bravery and gallantry.”

As these first excitements were dying out, 11 Cavalry had reached Chamb. The accounts are rather conflicting, but between 1100- 1200 hrs they had reached the outskirts of Chamb. The enemy RR’s, which had been sighted in the Chamb area, had knocked out a few of our tanks. The time at which Chamb was captured is still unclear, but the area West of River Tawi was seized by the evening, and the operation for the construction of a bridge- head across Tawi had started. By first light, on the 2TM of September, some units were struggling to make a foothold across the Eastern Bank of River Tawi. There was a lot of confusion because of a few vehicles getting bogged down in the soft bed of River Tawi. There was no enemy resistance, but the bridgehead had not yet been completed.

On the morning of the 2” of September, COC 7 Division was flown from his HQ at Jalalpur to Bhojpur, which was the location of the Tactical HQ of 102 Brigade. There, we got the instructions to proceed to Kharian, pick up General Musa who was arriving from Rawalpindi and bring him to the present location. We left for Kharian with two helicopters. General Musa, accompanied by Brigadier A.A. Bilgrami (VCGS), arrived in a U-8F, flown by Major Kureshy and. Major Madni. From Kharian, General Musa and Brigadier A.A. Bilgrami were flown in helicopters to the HQ 102 Brigade, where the GOC 7 Division had been dropped earlier. On arrival there, General Musa tried to contact Gen- eral Akhtar Ali Malik, GOC 12 Divi- sion, but he was not in communi- cation with anyone, neither on the wireless or landline. After a lot of ef- fort, he finally was traced in Chamb, where he was busy facilitating the redeployment of the guns of 4 Corps Artillery. There was an urgent need for firepower for the advance be- yond the Tawi River. After a lot of effort, a message was finally con- veyed to GOC 12 Division through the Headquarters 4 Corps Artillery, asking him to come to HQ 102 Bri- gade. Very reluctantly he arrived and was ushered in to meet General Musa, General Yahya and Brigadier Bilgrami.

In the bunker, a discussion took place which was inaudible for those of us standing outside. After some time Major General Akhtar Ali Malik came out with a gloomy expression on his face and some tears down his face. He later told us that although he wanted to remain in charge of the operation here, he had been ordered to take over the command of 12 Division at Murree. He looked dejected and broken hearted, as he had conceived and planned the operation from the start; it had meant a lot to him. It was a fateful decision. Was it with any specific intent? Was it to glorify Major General Yahya Khan, who was already being groomed as the next Commander-in- Chief? Was General Ayub under specific instructions from his masters not to push so far as to result in the inevitable capture of Akhnur? Could it possibly be that if Major General Malik had captured Akhnur, he would have become a national hero? Did this cause any alarm to General Ayub?

They all defy answers, as no one has ever explained the reasons for it. However, the fact is that it caused a delay in the battle’s progress and the capture of the ultimate objective of Akhnur. In my estimation it was definitely possible, as General Akhtar Malik had revealed all his intents and purposes in his orders, followed it up in the execution of his plan and the posture of his aggressiveness in command; they all por- tend to that. He planned to capture Akhnur on D+3 Day. However, the significance of this delay is a moot point; there is no way to determine this. It is only a guessing game, and the entire episode can only be described as our misfortune.

General Yahya took some time to assess the situation and held his “O” Group conference on the afternoon of the 2nd of September. The orders for establishment of Bridge Head, as planned earlier and under execution, were further elaborated by GOC 7 Division. He gave orders to both 102 Brigade and 10 Brigade to continue on the offensive on September 3, 1965. Brigadier Zafar was tasked to attack the Troti and Jaurian Positions from the north, and Brigadier Azmat was ordered to attack from the south. By 19.15 Hrs on the 2TM of September, the bridgehead was established by 102 Brigade, with 6 FF and 13 Lancers in the South and by 4 AK Brigade in the North. 6 Brigade under the command of Brigadier Iftikhar Janjua had also arrived in the area. He was ordered to take over the bridgehead to relieve 102 Bri- gade for their further action at Troti and Jaurian Positions. The situation as it obtained on the afternoon of the 2nd of September is at Annexure-36.

In the orders given earlier, GOC 7 Division had tasked 10 Brigade and 102 Brigade to secure Troti-Jaurian positions by last light on the 3rd of September. The outline plan of Commanders 10 Brigade and 102 Brigade were as follows: – 6 FF (Northern Battalion) to breakout from area of Pallanwala at first light on the 3rd of September and advance along line Chamb-Akhnur. Initially, mask Kalit and advance up to nullah/ road June (7367) and sweep southwards to secure Jaurian.

14 Punjab (Southern Battalion) supported by one Squadron 13 Lancers to break out at first Light on the 3rd of September. Initially, secure Nawan Hamirpur and after that advance eastwards along the river to threaten the enemy left flank to facilitate securing of Jaurian. 13 Punjab in reserve. To support this operation, elaborate artillery support had been planned. Enemy positions at Thoti and Jaurian were to be softened by heavy artillery fire, before the attack by 10 Brigade and 102 Brigade on first light on the 3rd of September. In the North, 6 FF and 13 Lancers met increasing resistance from enemy armour, Recoilless Rifles and Infantry, but advanced beyond Pallanwala. The opposition stiffened as our troops approached Troti. The enemy had flooded the paddy fields, which made the movement off the roads difficult for both A and B Echelon vehicles. But despite the odds, 13 Lancers Group had contacted enemy positions at Troti by 0600 Hrs on September 3, 1965.

In the South, 14 Punjab Group met little opposition from Nawan Hamirpur. The progress was also slow because of the flooded fields, which

subsequently separated infantry from Fighting Echelon vehicles. They did not go far enough beyond Nawan Hamirpur. The Brigade Commander 10 Brigade, Brigadier Azmat, showed a complete lack of willpower, proving to be inept at shouldering the responsibilities of command. He hardly exercised any control, lacked initiative and acted as a silent bystander to the ongoing operations, allowing operations to drift along, taking their own course. At first light on the 3rd of September, along with GOC 7 Division, I flew in an H x 13 helicopter from his HQ at Jalalpur to Chamb. At the helipad, Commander 4 Corps Artillery, Brigadier Amjad Ali Chaudhary met GOC 7 Division. When the GOC inquired about the progress of the attack, Commander 4 Corps Artillery explained that the fire plan had been executed on time and that the main attack was scheduled for first light. But according to his information, there was no movement on the ground.

When GOC 7 Division inquiringly looked at me, I told him that I would go and carry out a detailed recce. Flying in the H x 13 helicopter, Captain Askree and I flew across Tawi to the Troti position. As we approached the area, we found the whole position of Troti and Jaurian completely enveloped by a cloud of smoke and dust caused by the heavy artillery fire. The sheer weight coupled with the explosive impact of over 100 artillery guns had taken its toll with devastating consequences.

Suddenly, we saw a break in the smoke covered positions of the enemy. I asked Captain Askree to land the helicopter while I kept watch over the area. As we got closer to the ground, the smoke cleared, showing the actual effects of the artillery fire. Most of the surrounding area was in flames. Though we stayed on the field for a relatively short time, the situation had become clear to us; the enemy holding those positions was in a state of panic. Having had the benefit of seeing with our own eyes the situation as it appeared on the ground, we took off and flew back. We first landed near Troti and met 2 I/C, 6 FF. On inquiring, Major (Later Brigadier) Anwaar-ul-Haq told me that their F echelons had not arrived and because of that, they could not attack Troti as planned. From there I flew southwards, where we first met

Lieutenant Colonel Ata, CO 8 Medium Regiment and with his guidance, located Commander 10 Brigade, Brigadier Azmat.

When I asked the Brigadier about the progress on the ground, he explained that 14 Punjab was ordered to advance along River Chenab, but

they had lost contact with HQ, and because of this he was now in no position to push any further. We then flew toward the 13 Lancers, where I met Lieutenant Colonel Sher, their Commanding Officer. The unit’s tanks were all lined up in a nullah. The CO 13 Lancers explained that there was heavy enemy fire coming from Troti position, which was hindering their assault. After concluding this meeting, I headed northwards and met Lieutenant Colonel Siddique, CO 8 Baluch, and Brigadier Zafar Ali Khan, who was in Command of 102 Brigade. They too told me that because of enemy resistance and the rough terrain continuing with their advance had become increasingly difficult. I gave all the Brigade and unit commanders that I met, a detailed report and my assessment of the enemy positions in the area of Troti and Jaurian.

I put particular emphasis on the effect of our artillery fire and tried my best to influence their minds by stressing the need to resume with

our advance. They were being advised to bypass the Troti and Jaurian positions by using both the right and left flanks, but there was no reaction from them. Seeing this stalemate on the ground, I flew back to Chamb, where the GOC 7 Division and Commander 4 Corps Artillery were anxiously waiting for me. I repeated what I had told Lieutenant Colonel Siddique, Brigadier Zafar, Brigadier Azmat and all others, of my assessment of the situation. In my opinion, the enemy had been stupefied by the explosive impact as a result of the artillery fire. I felt that from these positions, the enemy could not offer much resistance and suggested that we should act without delay and launch the offensive.

I also told GOC 7 Division that I had tried my best to influence the minds of all the field commanders in the area of operations, but since I had seen no reaction from them, I firmly felt that only he could influence the situation. Major General Yahya had a sharp mind and grasped the critical points of my briefing. He had clearly understood the situation, and he spontaneously decided to act. He immediately flew out in the chopper with me to meet the Brigade Commanders. After taking off from the helipad, we facilitated GOC the opportunity to get a clearer and broader aerial view of the ground: enemy dispositions, the location of own troops and the big gap between Jaurian and River Chenab on the right and Jaurian and Kali Dhar feature on the left. Very quickly, the GOC sized up the situation and agreed wholeheartedly with my earlier assessment. The helicopter first landed near the Tactical Headquarter of 10 Brigade. The GOC was very upset and annoyed with the slow pace of the advance and his tone was rather harsh. In fact, he used most abusive and foul language. He told the Brigade Commander to go in the helicopter with me and take an aerial view of the area. He also instructed me to show him the enormous gap between Jaurian position and River Chenab. He also ordered that 10 Brigade should bypass Jaurian, and after having outflanked the enemy position there,

they should proceed along the road Jaurian-Akhnur. He further emphasised that any pockets of resistance at Troti and Jaurian would have to

be mopped up later. GOC 7 Division was then flown to the position of 13 Lancers and 102 Brigade. CO 13 Lancers, while explaining the situation on the ground informed Major General Yahya, that the enemy fire from the Troti position was preventing further advance.

Admonishingly, he told Lieutenant Colonel Sher, “The enemy will not be throwing rose petals at you,” and ordered him to continue the advance. His orders were clear and precise; 102 Brigade, along with 13 Lancers less one squadron, were to bypass Jaurian position from the left flank. The advance did not proceed at the pace that it was envisaged, but a useful outflanking manoeuvre was developed. It was at this stage that we received new orders; 102 Brigade with 13 Lancers were to capture Pahari Wala (6363) and begin advance through the gap in the enemy positions at Troti and the hills to its North. In the South, 10 Brigade was ordered to bypass enemy in area Jaurian and clear the Sahibwala Khad line without delay. 102 Brigade in the North and 10 Brigade in the South were instructed to secure the Kangar Nala line as soon as possible and then to advance and capture the GarahFatwal line Pt 968(8063). The orders were precise, but the terrain and flooded rice fields and the leadership’s lack of intent made progress slow and gruelling.

The earlier plan to capture of Jaurian by 102 Brigade and 10 Brigade, by last light on the 3“ of September, could not be accomplished because of a lack of intelligence on the enemy’s strength and exact dispositions. The rough and broken hilly terrain, the flooded paddy fields also played a part in this, but above all, the complete lack of will on the part of the two Brigade Commanders was the primary factor. Since a stalemate had ensued at Troti, explicit instructions were issued by the GOC to bypass the enemy positions there and to carry out an outflanking move. While the 102 Brigade was developing the flanking movement from the north and 10 Brigade from the south, Army Aviation remained actively involved with the operations. At this stage, heavy gunfire was successfully holding back the advance of own troops. G-II (Ops) 4 Corps Artillery, Major (Later Colonel)Aleem Afridi ordered the pilot, Captain Khalid Saeed, who was providing close support to these operations, to silence these guns. As Captain Saeed gave the grid reference and started adjustment of artillery fire at those positions, GII Corps Artillery, Major (Later Colonel) Aleem Afridi became very perturbed. He did not believe that the grid reference that Captain Saeed had just given was correct.

He was strongly telling him that own troops had gone beyond that line. Captain Saeed told him that since he was creating a doubt in his mind, he will fly over the position to confirm and clear the situation. That was his daring! As he flew overhead the enemy gun position, small arms and automatic weapons opened up, and the aircraft was riddled with bullets. The right fuel tank was critically hit and ruptured, sending gushing fuel into the cockpit of the plane. Captain Saeed, maintaining his calmness, said to Major Aleem, “Now there is no doubt in my mind. This is the position of the enemy guns, which is withholding the advance of own troops. Now concentrate all the guns here and bring down maximum fire.” Captain Khalid Saeed was lucky that he landed safely and the aircraft did not catch fire. The intensive and accurate concentration of own guns on this position had its telling effect. Because of this intensive fire and also the outflanking moves of 102 Brigade and the 10 Brigade, the enemy abandoned these positions. These were around near area Kalit. They left behind 24 guns;

Eight of them were still hooked behind their towers with their engines running, and the remaining sixteen remained still deployed in their

original positions. The enemy also left behind a full squadron of AMX tanks, a lot of other equipment, vehicles and ammunition. Later, Major General Tikka Khan, along with Lieutenant Colonel (Later Brigadier) Nur Hussain, went into the area and collected all the booty. For this brave act of Captain Khalid Saeed, I initiated a recommendation for him for the award SJ, which he did not get but was instead conferred with the award of Imtiazi Sanad. This deed by Captain Khalid Saeed, however, did Army Aviation proud. The events on the 4th of September turned out to be very significant in the operations of Jaurian. This position was very strongly held by the enemy; it was roughly composed of 2 Battalions, a Regiment less one squadron of AMX tanks and supported by a field regiment in the Area of Kalit and additional medium guns deployed behind that position. The outflanking moves by 10 Brigade from the right flank and 102 Brigade from the left, besides the direct attack at Troti and Jaurian, had unnerved the enemy. Its position at Troti and Jaurian cracked, and they had abandoned these posts and retreated. The initial artillery fire had a devastating effect on the enemy positions. By evening on the 4th of September, the enemy had almost entirely withdrawn from Troti and Jaurian, and by the subsequent morning, the Troti and Jaurian positions had been captured, and our troops were advancing on to Akhnur. Annexure 4’, Army Aviation had played a central role in the development of the outflanking move.

First, through a detailed, intensive and accurate assessment of the battlefield situation; Army Aviation had done battlefield surveillance, gathering much needed vital information. By flying the GOC 7 Division into the area and giving him a professional briefing along with the aerial view of the battlefield, the fog of war was cleared rapidly. The information collected when the helicopter had been landed in the midst of the enemy positions at Jaurian was most eminent in this; it helped determine enemy dispositions in that area, and in identifying significant gaps in their defences on both their right and left flanks. Army Aviation had also come up with a tactical plan which entailed

attacking from the flanks and not from the front. The stalemate that had ensued at Troti and Jaurian had brought about a somewhat breakdown of command and control of the formations. The F Echelons of some units was lost, the Brigade Commanders had lost contact with some of their units, and the momentum of attack at Troti and Jaurian had not fully developed.

It was largely through the efforts of Army Aviation, by their timely information and advice, that this stalemate was broken. In separate orders 4 AK Brigade Commander Brigadier Hameed was given the task of capturing the Kalidhar feature on the left side of the route leading to Akhnur. It was to commence on first light on the 4” of September. Wireless messages kept pouring in about the progress being made. It was towards midday that the Brigade Commander personally gave the message of having captured the top of the Kalidhar feature. He was profusely congratulated by Major General Yahya Khan, who had already been in a state of euphoria after having received reports of the progress being made. However, this was short-lived. A little later, a call was made about the heavy enemy counter attack on the positions recently captured on the main feature. Sometimes later the news was sent that in the face of heavy Indian Attack, the top of the feature had been evacuated and our own troops were now occupying lower slopes on the ridge.

Then again there came the news of another enemy attack at those positions now supposedly held by own troops, and the story of having to

abandon this was repeated. Alarmingly, further messages kept coming in of our own troops retreating. Towards the evening, 4 AK Brigade

troops seemed to have returned to the same point from where they had launched their attack in the early morning. At this stage, Major General Yahya Khan got into an uncontrollable rage. He was on the wireless himself, shouting at Brigadier Hameed, “You (expletive)! It is now clear that you have been painting pictures to me the entire day. You never moved out of your location. The entire operation was based on a farcical description!” Why he did not remove him from his command, I could not personally understand? But the most ironic thing was that when General Yahya Khan assumed the Command of the Army, he promoted him as Major General and then later as Lieutenant General. I was totally disillusioned! Soon after Jaurian position was captured/bypassed on the morning of the 5” of September, the advance to Akhnur proceeded. 10 and 102 Brigade spearheaded the advance. In the South, 13 Punjab (10 Brigade) made a swift movement along the northern bank of River Chenab and cut the road Jaurian-Akhnur in the area of Dalpat (10 Brigade objective) by 0915 hrs. The advance of 6 FF and 13 L on Fatwal was held up by enemy rearguards, which were rounded up by 14 Punjab from the South. The Mawawali Khad line was reached on the evening of the 5” of September.

It was estimated that the enemy which had fallen back from Chamb, Troti and Jaurian positions, would have taken posts in the foothills of

Akhnur. It was also estimated that at Akhnur, we would be up against the key defensive position. Under this misconception, the infantry advancing to Akhnur failed to carry out any aggressive patrolling. The Army Aviation was also handicapped since it was getting dark, and perception was very limited. The position of the enemy defences at Akhnur was unclear and this lack of information proved to one of the

most vital factors contributing to the result of the 1965 war. The Fatwal ridge positions held by the enemy had been overcome and we had

advanced beyond that; we even reached within 2-3 miles of Akhnur Bridge at River Chenab. -Annexure 5°.

The fundamental principle of war (aggressively following the retreating enemy) was ignored and not followed. The forward elements failed to carry out any patrolling. Major General Yahya Khan was not forward enough to personally influence and push them to move on. It is the irony of fate again that Commander 10 Brigade Brigadier Azmat was in the lead. True to his performance as on the 1, 2” and 3” of September, he failed to aggressively pursue an advance towards the bridge at Akhnur. This also brings out some difference in the aspect of Command between the two force commanders in this sector. Earlier, General Akhtar Malik was right on the tails of the leading Brigade Commanders and also milling around in the gun positions to personally oversee the operations; control and guide it. But General Yahya, to the contrary, was exercising his leadership through the routine channels and customary chains of command. Akhnur had been our primary objective, and its capture was a pivotal part of this operation.

Having reached within 2-3 Miles from the Akhnur Bridge and the glimmering lights of Akhnur well within our sights, why was there no urgency to probe, move forward and capture this crucial target? All of us who were in the field and other defence critics and analysts kept asking this question up to this day. The retreating enemy had not picked up the courage to take positions at Akhnur. In fact, they withdrew

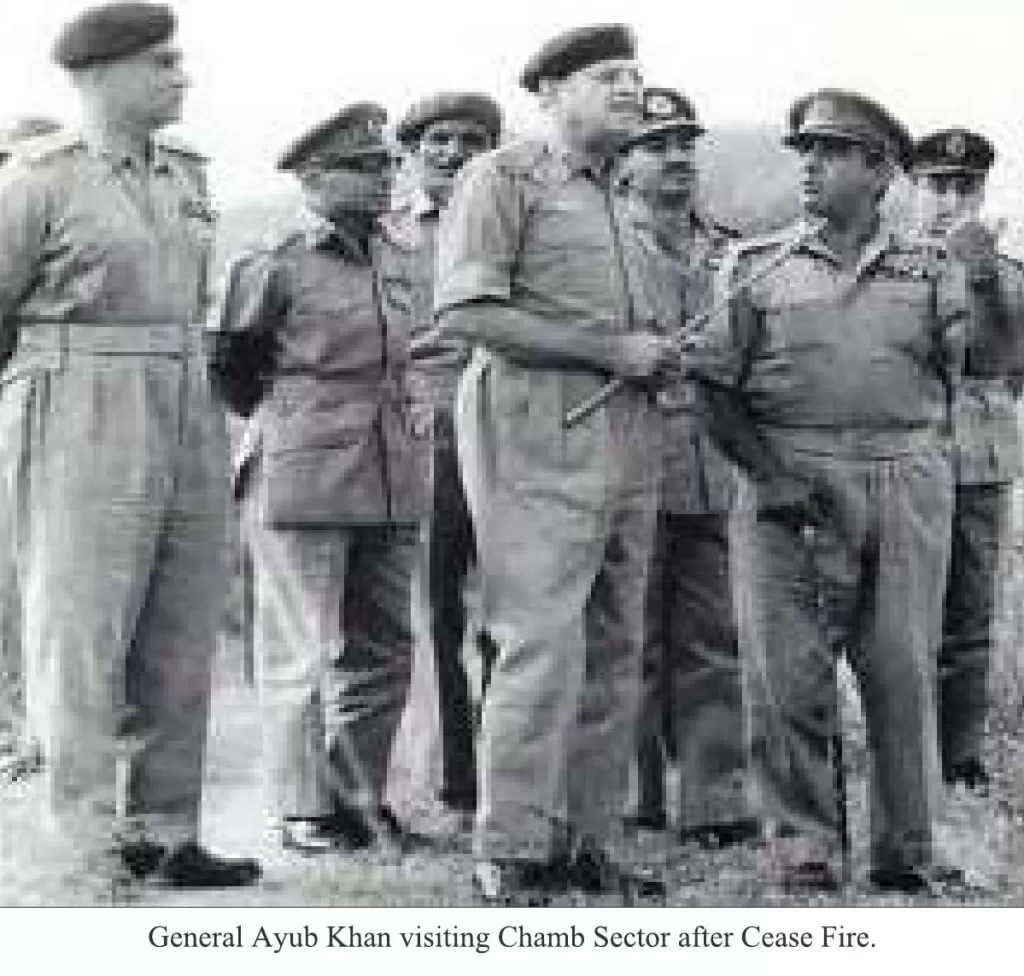

across the bridge at River Chenab. Akhnur Bridge was abandoned and left empty on the night of 5/6 Sept, almost as if it was beckoning us to move in and capture. It is unfortunate that we failed to achieve this important objective. The enemy, realising this, reoccupied Akhnur positions on the morning of September General Yahya confessed that it was the biggest mistake that he had made in this war. Here, I will reflect again on the remarks I made earlier regarding the change of command. Was there a motive or a purpose in it or that it was only an honest mistake?

A United Nations Military observer, who was posted on the Indian side of the Line of Control, came over to Jaurian area after the Cease Fire and bluntly asked the reason we weren’t able to capture Akhnur Bridge. Many Pakistani Officers who had been attending various courses abroad had been asked this question from their Indian counterparts on those courses. They were told that they could not understand what

prevented the Pakistan Army from capturing the Akhnur Bridge. There was no ready answer available then and even now in hindsight. Situation at cease fire -Annexure-6. This anomaly can only partially be answered by a letter which Major General Akhtar Malik later wrote

to his brother from Ankara. Annexure710 It helps throw some light to his frustrations and motivations regarding the whole incident before

the advance towards Akhnur and the ultimate objective of capturing the Akhnur bridge. It suggests that the change of command, which he describes as de facto, had already taken place at the very first day of the operations after the fall of Chamb.

He subscribes this to the fact that Brigadier Azmat Hayat Khan, Brigade Commander of 10 Brigade, had broken off all wireless communications with him. He further elaborates that when he tore into him the next day, Brigadier Azmat sheepishly informed him he was Yahya’s Brigadier, and answers to him only. Iam personally not inclined to agree with this assessment and analysis. I was privy to these events and was in close touch with Major General Yahya Khan, and I believe no such instructions were given to Brigadier Azmat Hayat. The conduct of Brigadier Azmat speaks volumes by itself; not only did he remain out of communication with the GOC of 12 Division on September 1,1965, but he repeated the same practice with the GOC of 7 Division later. In my presence, Major General Yahya, on September 3,1965, rebuked him for his actions. That he had begged Generals Musa and Yahya to allow him to join the advance up to Akhnur, even

under the command of Major General Yahya, is most probably true. At first light on the 6” of September, as per the routine of the last

few days I was going to the mess to have my breakfast. GOC 7 Division came rushing out of his caravan.

On seeing me, General Yahya said that General Musa was on the line a short while ago and had told him that the Indians had attacked Pakistan across the International line. The attack had come at the Jassar Bridge, Lahore and the Kasur Sector. He was also informed that the

Jassar Bridge had been captured. While conveying this news to me, GOC did not believe that the Jassar Bridge could have fallen and captured so easily by the enemy. On my inquiry as to why he did not believe in this, GOC 7 Division remarked that this position is being

held very strongly and firmly. Since this doubt was created, I suggested that he let me fly over the area to see the situation on the ground, to which he agreed. When I flew over the Jassar Bridge, I saw the fighting taking place across the Bridge; beyond our enclave on

the Indian side of the Bridge. I flew over the whole of the position of 115 Brigade, and this close aerial view gave me a very reassuring picture. The Bridge was intact and in firm control of own 115 Brigade. From here, I went straight to the 15 Division HQ, where nobody was

sure regarding the situation at Jassar Bridge. The GOC, Brigadier Ismail, whose only claim to Command was that he, like General Musa, was

Persian speaking, appeared to be a passenger only. Colonel S.G. Mehdi, who was my Company Commander at PMA, had seemed to be in charge. When I informed them both that I had just flown over this position, there was a look of anxiousness on their faces. On being told, that the Bridge was intact and that the fighting was taking place across the Bridge in the area of our own enclave with the 115 Brigade positions firmly intact, there was a sudden rush of liveliness.

Colonel S.G.Mehdi picked up the phone and called the DMO at GHQ. He told him that he had disobeyed the orders of HQ | Corps for the

blowing up of the Bridge at Jassar. He further said that he might be Court Martialled, but he had willfully disobeyed these orders. He

was vehemently pleading with the DMO, that the HQ 1 Corps had under some misinformed judgment, given these orders. Colonel Mehdi

now appeared more composed, relaxed and in command. I had known him, and I hoped that with his background, he could grapple with the

situation and bring in some sanity and some sense of direction at the Division Headquarters. It was immediately clear that there was a total

lack of proper communications and understandings between Corps HQ and the Divisional HQ. On hearing the news of Jassar, the telephonic conversation with the DMO and the reassuring discussions of the overall situation, there was finally some normalcy in the atmosphere of the Divisional HQ. Colonel Mehdi told me that on the 5” of September, an enemy dispatch rider had been captured, and in the mail that had been gained from the rider were some letters that were addressed to the personnel of 1 Armoured Division. From these letters,

it was clear that the enemy Armoured Division was now in this area.

Colonel Staff gave these important letters and documents to support this to me and asked me to take these out to GHQ. This was done promptly, and GHQ had this information on September 6. Colonel Mehdi further told me I should reassure Major General Yahya that his old formation will not let him down. I flew back to Tactical HQ 7 Division at Chak Pandit where GOC 7 Division was waiting very anxiously for me to hear the latest news about the situation in the Sialkot Sector, in particular, reference to the position at the Jassar Bridge! When he was informed that his appreciation of our own strength at Jassar was correct and that the bridge was intact, he very excitedly exclaimed, “Did I not tell you that?” He further said that he as GOC 15 Division, had planned the entire defence of the area; he had walked the whole area on foot and had planned the defence of the area to the minutest details. Emphatically, he explained, “The logical line of the enemy attack will be Charwa-Chobara-Phillarauh-Chawinda”.

The mention of the names of these places did not ring any bell in my ears, at least not at that time. But the words seemed to be prophetic

on September 8, 1965. The significance of this only dawned on me in the coming days as the events unfolded themselves. When I transmitted the details of my discussions at 15 Division HQ and particularly the message that Colonel Mehdi had sent to him, he just scoffed it away. Apparently, Colonel Mehdi, for what reasons I do not know, had fallen in his eyes and estimation.