Zhao Lijian, the then Deputy Head of Mission Embassy of China in Islamabad, who is currently a spokesperson of Foreign Ministry of China, to a question from one of my colleague, Raza Khan who is Chief Correspondent for PTV World, as to why we (Pakistan) cannot see China-speed on CPEC projects?, humbly replied, “How can we show you China-speed (in development) on CPEC projects when you have multiple layers of decision-making structure in Pakistan. We (Chinese) come and finalise projects with your Federal Ministry of Planning & Development, but then we face hurdles when the files related to those ‘agreed projects’ are held up by the provincial government(s). …Then when we cross that hurdle then some entity (elsewhere) creates obstacles….”

The learned diplomat was candid and a true fiend of Pakistan as, at least, he was able to understand what ails Pakistan’s progress and prosperity at the hands of vested status quo forces. This is how one can sum up to begin the trajectory of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor’s path of blossoming, ten years since its inception.

The multi-billion dollar mega-project, CPEC, is all about Pakistan’s socio-economic future, and inevitably related to our survival as a viable nation in an era of alliances. During the last seven decades of our existence, no investment to the tune of such a magnitude had ever hit Pakistan. Though the country has been recipient of billions of dollars from the United States, it has been defence-centric or on projects directly vetted, monitored and executed by Washington in realms related to a fewer number of avenues in education, women empowerment and societal development.

Whereas, the staggering $60 billion promised investment under the umbrella of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) flagship program, CPEC, is certainly a game-changer. It has revived for good Pakistan’s regional perception, and impacted its foreign policy by driving it away from being a clientele state of the United States. This bogey has come with consequences too, as many economists term the China-leaning as a debt-trap, and one that will isolate Pakistan for good by making it a bloc-centric neighbour of the Red Dragon.

CPEC, irrespective of its shortcomings and cross-currents, is a ‘Deal of the Century.’ Statesmanship demands that no stone should be left unturned to exploit its potential, and to ensure that infrastructure and industry is revitalised, come-what-may. But it is quite unfortunate that a decade of development has not produced the desired results. Moreover, development has been lopsided and not genuinely has been successful in involving stakes of the locals. It is a common observation that resentment and revulsion is the order of the day in the theatre of CPEC, i.e., in the desolate province of Balochistan, and Gwadar is a case in point.

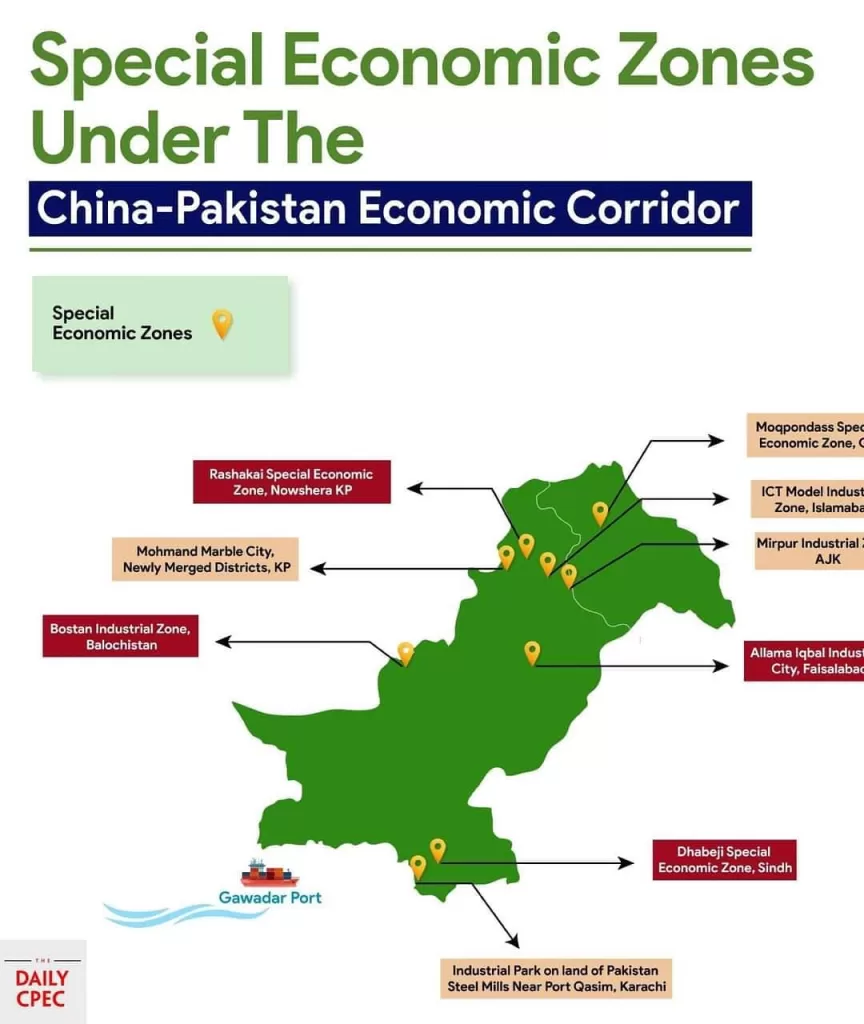

With nine Special Economic Zones (SEZs), likewise, dotted countrywide, none are in business, and their setting-up is still a far cry. The reasons for this deliberate failure are rooted in, as stated by Zhao Lijian, a perpetual row between the federation and the provinces. The 18th Constitutional Amendment, which torpedoed the power balance and avenues of distribution of resources, has come to weaken the federation, and respective provinces with all the necessary muscles, as epitomised by Shakespeare, are found wanting in extracting a pound of flesh without spilling a drop of blood.

As CPEC enters a new decade of tribulations, this erstwhile paradigm must come to an end. There is no luxury to miss the bandwagon of geo-economics, which will certainly go ahead under Chinese leadership, whether Pakistan hops on to it or not. It must be borne in mind that while Pakistan sits at the crossroads of a strategic nexus, having an assured say in any of the BRI’s articulation, there are other alternatives

too if Islamabad does not overcome its shackled decision-making mechanism. Connecting Central Asia and Afghanistan via Iran, and rerouting Indian trade via Chahbahar are possibilities ripe on the cards.

Pakistan will certainly have to double-down its race as it cultivates the new leadership in Kabul for a permanent peace, and likewise mends fences with New Delhi. A constant state of historic animosity and one that is based on bad blood will not reap any dividends. China’s pouring in of investment is an opportunity, and it certainly comes with a cost and a staggering demand to reorient. The first phase of CPEC has seen Islamabad receive up to $25.4bn in direct Chinese investment in various projects. This is in addition to the huge loans and currency swap of CN¥30bn that came Islamabad’s way over the last 10 years to keep its wheel of fractured economy rolling.

The literal turnaround has been in transport, energy, and infrastructure schemes. The motorways of Hazara-Abbottabad, down the south towards Islamabad-Lahore, Dera Ghazi Khan-Mianwali, and deep into the terrain of Balochistan is a miracle to say the least. Beijing has connected Pakistan’s landmass to international standards of logistics and transportation, and there is much that is in the making, including the ambitious M1 parallel railway link, and new hydro-electric dams.

To count on the least side, an estimated 250,000 jobs were created till the end of 2022, and is a befitting outcome for a country that was down and out in the wake of post-9/11 upheavals in the region, and the Americans obsessed with flying of drones over its landmass in their trigger-happiness of hunting non-state actors both in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The second episode of Beijing’s largesse is all about industrialisation. This will see business-to-business ventures and not much government-to-government regulations. It is a phase of connecting the infrastructure with production houses, and this is where we cannot afford to blink. What is required is a resilient and sustained strategy to raise the benchmark of our production, and in doing so the critical aspect will be the cost of doing business and the ease to do it without much ado. Can Pakistan do it with its present exorbitant tariffs of electricity, gas and surcharges? Absolutely, not!

This is where a new regime of development and one that is nationalistic in perspective is desired, and not one that creates avenues of minting money for the power-brokers and wheelers-and-dealers. Certainly, Pakistan will have to emulate the Chinese module, if it endeavours to push back poverty and rise as an evolving enterprise. The art of doing business with Chinese firms must change. Enough of being a dumping ground of inferior goods, and notoriously involved in kickbacks. It is common knowledge that Chinese private businesses can be bribed, and the trend is in vogue worldwide.

Pakistan must pronounce its labour and raw material avenues to tap know-how for upgrading its imports, and the intention should be to ensure value-added products. While growth comes with a balance of payment crisis, this must be addressed through long-term planning. A sustainable export policy is needed on an exponential basis, as the whole economic enterprise must be in trilateral coordination of the ecosystem, stable and timely decision-making. The lesson is that China has managed to browbeat lethargy, and pull 70 million people from the abyss of abject poverty within a span of 30 years by virtue of political stability, continuity, peace and social solidarity. Pakistan must redo its business acumen to engage with China as a strategic business partner, and not one that is there to dole out tranches of money when

faced with a deficit in balance of payments.

Has anyone ever thought of making China as Pakistan’s biggest importer? Beijing imports $2.7 trillion of goods, and our input is a mere less than $2.5 billion in the Chinese economy. Time to wisely engage and convince the Chinese that it must set up production units in Pakistan too as it has done elsewhere in Southeast Asia and Africa. What is the essence of CPEC if we can neither produce, nor enhance our exports by making use of shortened connectivity down to the Mideast and Africa and up in the north with Central Asia? Being a mere route facilitator and night-watchman for logistics is no big deal!

The good point is that perceptions are changing, and the State of Pakistan is responding organically. The creation of the Special Investment Facilitation Council under the civil-military combine is a rightful recognition. But it is worth-mentioning that there used to be a CPEC Authority too under the watchful eyes of Military General in the yesteryears. What came out of it is still an enigma. This points out that mere establishing of panels and commissions is not enough, if not supplemented with a vision of sustenance in policy-making and implementation. Certainly, SIFC has to be different from previous faulty experiences, and the minimum that is needed is a one-window operation in essence and to do away with the prevalent 38-sockets of vetting a file. It is desired that state-of-the-art professionals must be involved in dealing with the investors, and to eliminate the role of our traditional bureaucracy. A policy-implementation forum free from ministerial interference is the key to success in an era of Sovereign Wealth Funds, and CPEC too must be tried and tested on the same hallmark.

It is all about expansive connectivity, and that too without any politico-perceptional feuds. This is what differentiates the Chinese strategy from its rival counterpart forces, who believed in development on adhering to the same ideology. Western Europe being built by keeping the East in shambles is a case in point. As far as Pakistan is concerned, while being the largest and most effective strategic partner of China, it must tweak its outdated industrial and agricultural policies to attract confidence and technology, and not merely investment. Islamabad also needs to close the trade deficit of around $20bn with Beijing. That is not possible without quickly completing the SEZs, and at the same time convince Chinese businessmen to relocate their manufacturing facilities here, and export back the finished goods back to home and elsewhere.

Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and many other Southeast Asian states had pursued a similar strategy by influencing American mega-firms, and became billion-dollar-centric franchises. Nothing should ail us in broadening our vision, and instantly do away with conditionalities list in picking and choosing who should invest in what? While CPEC enters the second decade of engagement, it should also be kept in mind that the Chinese economy is struggling. The growth graph is shrinking primarily owing to debt-fueled and investment-driven growth models within and outside the Mainland. Post-COVID, Beijing has posted the slowest growth in decades, and it will inevitably have a sour influence on recipient states like Pakistan. This is where wise leadership, and a vision for the future is needed in geo-political-cum-economic dimensions. Nothing should compel the Chinese to put away the purse and largesse. Islamabad is poised with a strategic business challenge in months and years to come.