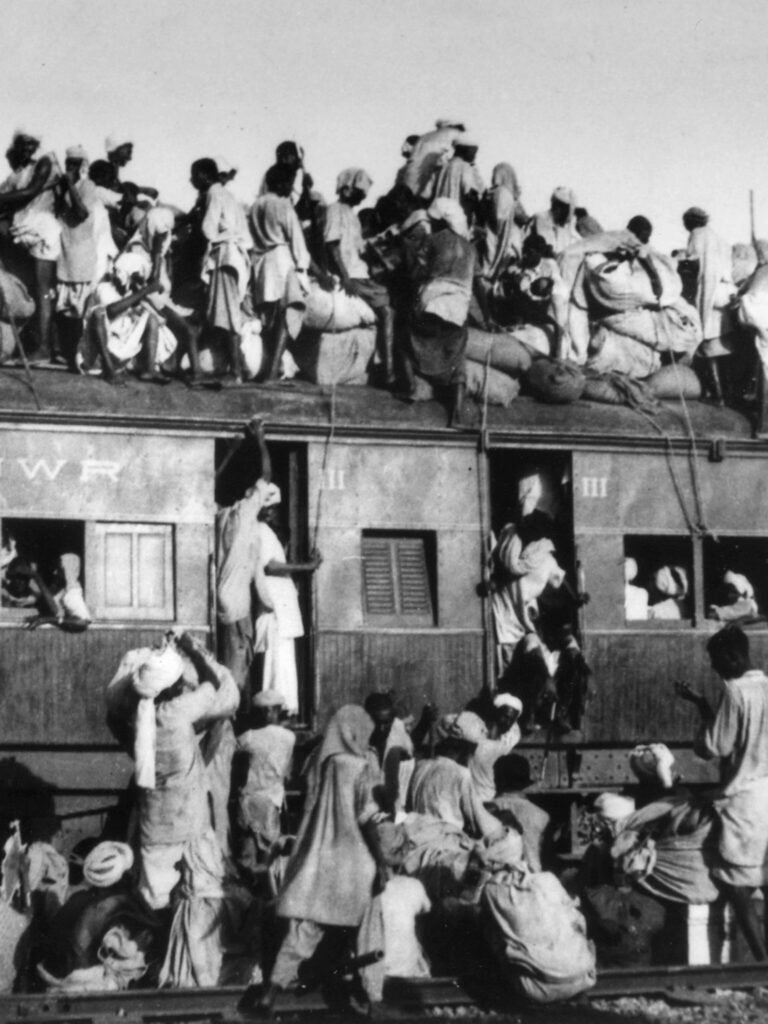

A number of authors from across the globe have examined the history of the post-partition subcontinent because the British colonial retreat from the subcontinent laid the foundations of the enduring India-Pakistan rivalry and added another chapter in the history of the subcontinent. The partition ended the colonial era and initiated a multilevel hostility between two neighbouring powers, India and Pakistan. The initial leaderships of both states developed their inflexible territorial disagreements on various points and marked Kashmir as a gravitational point of their hostility. The subsequent phases of the subcontinent’s politics witnessed various phases of the intense regional security environment in which New Delhi and Islamabad persisted in multiplying their points of disagreement over different issues.

These disagreements further caused the contesting standings of New Delhi and Islamabad in regional and extra-regional affairs. In response to the growing hostile interstate interaction between the two neighbours, the leading circles of international intellectual communities started expressing their opinions on the evolving rivalry between the two major powers of South Asia. The book under review is an intellectual effort of a Pakistani scholar, a renowned academic figure formally known as the Distinguished National Professor and Professor Emeritus in Pakistan. He has served in the country’s top-ranked university, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, and shared his intellectual insights on various national and international academic platforms.

Tariq Rahman is the Dean of the School of Education at Beaconhouse National University, Lahore and extensively writes on various topics related to Pakistan, including its history, culture, and politics, and focuses mainly on Pakistan’s position in the subcontinent concerning the decades-long hostility between India and Pakistan. The book Pakistan’s Wars provides a comprehensive analysis of Pakistan’s involvement in the inter-state and intra-state wars and the internal dynamics of these wars, with an exclusive emphasis on Pakistan’s decision-making mechanisms relating to the wars. The main debate of the book is divided into twelve short chapters, including Introduction and Conclusion. After formally introducing the main theme of the book in the first introductory chapter, the author covers different topics in the subsequent chapters parallel to highlighting the nature of different conflicts which transformed into unavoidable wars for Pakistan.

The second chapter provides an exclusive account of arguments concerning the decisions of war and the military’s role in initiating these wars. It has examined the changing attributes of domestic politics under different military rules (p. 30). The rest of the debates in six chapters stressed emphasis on the wars of 1947-48, 1965, and 1971 (the experiences of Pakistan and Bangladesh), the Kargil crisis, and the prevalence of Low-Intensity Conflict in South Asia. The last part of the book has compiled the experiences of the people affected by the wars parallel to explaining their miserable condition in the post-war scenarios. Rahman’s book offers a nuanced and critical analysis of Pakistan’s role in the major wars which were fought under anti-Indian and anti-terrorist slogans. The decisions of these wars raised various questions on the disturbed civil-military matrix of the country in which the civilian and military leaderships faced various challenges. These challenging scenarios left negative impacts on the outcomes of wars and caused a trust deficit environment in the domestic politics of Pakistan.

In this way, it is more appropriate to maintain that the analysis of Rahman is an analytical survey of Pakistan’s civil-military relations which has passed through various phases while witnessing several incompatibilities. The wars of Pakistan with India and then with the non-state actors were unavoidable for Pakistan, but the decision-making mechanism regarding initiating wars produced various questions.

Rahman’s analysis has attempted to answer these questions by accessing various primary sources, such as the interviews of people affected directly and indirectly by the outbreak of these wars. Thus, the inclusion of interviews with widows, children, common soldiers, Internally Displaced People (IDPs), refugees, and villagers living near the borders remained the central point of Rahman’s arguments in the book. The addition of the untold stories of the people affected by the war is an exceptional feature which enhances the legitimacy of the arguments in the book. An appreciable equilibrium between both data sources, primary and secondary, further increased the validity of the author’s findings in the book. Through a detailed analysis of primary and secondary sources, Rahman provides a critical perspective on Pakistan’s wars, challenging some of the prevailing narratives and assumptions surrounding these conflicts. His book offers a valuable contribution to understanding the complex and contested history of Pakistan and the subcontinent.

Rahman is a well-respected scholar and writer, and his book has been widely recognised as a valuable contribution to understanding Pakistan’s military conflicts with India. In this way, Pakistan’s Wars could be treated as an account of exceptional arguments for people interested in studying the non-traditional approaches to analyse the history of the subcontinent. Furthermore, students of South Asian politics can find it an interesting reading which could provide them with a different perspective to understand the position of Pakistan in the conflicted regional environment of a nuclearized subcontinent. The depth of analysis, rigorous research, and Rahman’s critical perspective has made it a significant contribution to the existing literature concerning the hostile regional politics of South Asia.