I vividly remember former Indian Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral once saying, “there has to be a dispute between India and Pakistan; and even if they come to resolve the Kashmir issue, they will invent another one…”. Though sarcastic, the par-excellence diplomat was not wrong, per se. The crude manner in which New Delhi on January 25, 2023 issued a notice to Pakistan, calling for the modification of the historic 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, sounds myopic. The fact that it threatened to unilaterally pull out of the covenant sounds too immature of its reading on International Law.

Before we dwell into its catharsis, let’s do some quick introspection of the profound water accord that has survived three major wars, truncation of Pakistan and a disdained bilateral relationship for more than six decades.

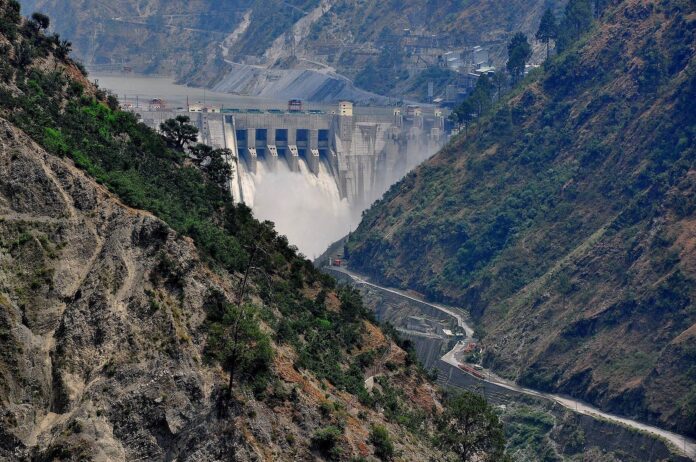

The Indus that initiates its arduous journey from southwestern Tibet after swirling through the mountainous picturesque Kashmir enters the plains of Punjab before submerging into the Arabian Sea. It is one of the world’s most articulated riverine paths. This is called the Indus Basin for ages.

The post-Colonial Indian subcontinent also saw the division of rivers, like men, material, blood and terrain, and the landmark water sharing deal between the two immediate neighbours that nurse extreme animosity was signed after nine years of negotiations in 1960.

The fact that it has lived till to-date with the World Bank acting as a broker is a splendid achievement of statecraft resilience that is hard to find, otherwise, between the duos. What ails to this day despite unanimity in the water accord, and why both the countries keep on posting their complaints, is that the treaty partitioned the basin by allotting three eastern rivers – the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej – to India, and the other three Western rivers – the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum – to Pakistan. Thus, with the passage of time climatic changes and population swifts have posed new challenges, and the down-streaming of water is making both the states adjust to new realities.

It goes without saying that while Pakistan is a lower-riparian state and around 90 percent of its agricultural produce depends on Indus water. It is also a fact that at the time of the deal, around 20% of water at source went its way to India, and it had to sign in to limited rights of non-consumptive use on the Western rivers, such as in irrigation, water storage and hydropower.

This is why following a disagreement on the designs of the Kishenganga and Ratle hydropower projects in 2016, Pakistan and India both made two different pleas to the World Bank.

These riddles keep on resurfacing again and again with new problems of the day. To describe it in a jiff, Pakistan made a request for the empanelment of the Court of Arbitration, under Annexure G of the IWT, and likewise India went on to plead appointment of a Neutral Expert under Annexure F of the treaty. However, due to problems related to continuing with the two processes simultaneously, in December 2016, the World Bank “paused” the dispute resolution mechanism of the Treaty.

Fast forward, as both the compliant states failed to reach a settlement over the discord, the World Bank finally decided last year to continue with both: the empanelment of the Court of Arbitration and the appointment of the Neutral Expert.

Then onwards, it is a tale of action and high reaction, with India hinting at terminating the treaty. Those turbulent words from New Delhi are no less than a hoax, and Pakistan should focus its synergies more on an appropriate response in the legal jurisprudence than on flimsy reactions.

To quote Article XII of the Treaty, it says, “… neither modification, nor termination can take place without the consent of both Pakistan and India.”

So, what’s now? The good thing is that both the countries are alive to their responsibilities and, perhaps, it is the only agreement that elicits periodic meetings among Water Commissioners, without a fail. Another such responsibility discharged with enthusiasm is the exchange of list of nuclear installations, by year-end, amicably and in a pacific manner. This paints a case of congeniality even in adversity at the hands of being tied to international compulsions. Let’s see, of late, what are the strong impulses between the two states, and as to why the Indus Water Treaty is back in the spotlight. It has, surely, to be read in a broader context with a pinch of introspection. There is a catch-22 dilemma!

As the IWT Commissioners’ met in 2021 in the backdrop of a verbal thaw between the then Prime Minister Imran Khan and his counterpart Narendra Modi, it came with a vista for relaunching a new understanding. It was soundly supplemented by a desire from the powerful Establishment of Pakistan for starting a process of composite dialogue – though those were not uttered in so many words.

The then Army Chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa told the Islamabad Security Dialogue, 2021, that it was time for India and Pakistan to “bury the past and move forward”. He emphasized water and climate change as spontaneous challenges facing the region.

Of course, those words had a backgrounder, and the undeniable necessity that environmental somersaults are directly related to regional economy and the land-based growth module. The Pakistani leaders were on the same page, perhaps!

Maybe that was read as a sense of negativity from the lower riparian state, and India simply started reading too big a plot in it. The call from Pakistan would not have come at a more opportune moment. It was at a time when the ceasefire across the Line of Control, brokered under the good-offices of the United Arab Emirates, was holding and reportedly spymasters from both the countries were in informal parleys. It has to be recognized that water and climate are the two most irresistible factors that will have a say in India-Pakistan relations, and not land-based disputes or political animosities on fudged up doctrines of otherness.

Global warming is causing glaciers to melt, a region where most of the world’s glaciers are located, causing the basin in the Himalayas to overflow. Though the downstream water from these glaciers will give India more water in the short term, with the passage of time, it will turn out to be an enigma for Delhi, which will be compelled to erect more dams, accordingly. This is where the fine-print of discord rests. While Pakistan consciously has called for cooperation in water and climatic issues, it is India that wants to play foul, and the recent IWT stunt has simply made it clear. Pakistan has time and again accused India of violating the treaty by building dams on the western rivers, where India maintains that these are ‘run-of-the-river’ projects’ permitted under the treaty.

What is needed rather is a renewed understanding between Islamabad and New Delhi to cement the Indus Treaty will fresh political impetus, and make use of the valuable resource-base, as well as the law, for common good. IWT encourages cooperative transboundary development and smart resource allocation, and this is a great denominator to build on new epilogues.

The way forward is to simply recognize that the world around us is changing, and so is Nature. India, as the fifth largest economy of the world and second largest population, should lead from the front and, at least, prioritize climate change and water issues in its bilateralism.

The first step for a millennium-long journey is by recognizing Pakistan’s water crisis. This precious source of water can swing in many a political and geographical solutions, as environmentalists and social scientists could propose a viable open-border status for Kashmir, and pave way for more amalgamation of Nature-centric ideas on Gilgit Baltistan and Ladakh, as far as the tributary is concerned. It could be an out-of-the-box proposition, with plenty of dividends.

If Israel and Jordan, with so much of animosity and bad blood, can sign a water-for-energy accord termed as ‘Project Prosperity’, what ails India and Pakistan? A Memorandum of Understanding will obligate Jordan to produce 600 megawatts of solar power capacity to be exported to Israel, and in lieu the Jewish state would provide water-scarce Jordan with 200 million cubic metres (mcm) of desalinated water. An articulate understanding that fits their national interests, especially taking into account the ramifications of climate change in one of the most volatile regions of the world.

There are many threads from the deal that Jordan and Israel signed under the auspices of the UAE. As the UAE recognized Israel under the Abraham Accord in August 2020, it opened doors for techno-economic cooperation wherein an Emirati government-owned firm, Masdar, would construct a large solar power facility in Jordan, which would produce electricity by 2026. The electricity will be sold to Israel for $180 million dollars per year.

The underlying point is that UAE is Pakistan’s all-weather benevolent friend. It is home to around 1.5 million Pakistanis, and has been consciously playing the role of an honest broker between India and Pakistan, and the 2020 ceasefire deal is a case in point.

Can the establishments of Pakistan and India draw courage and go ahead with a climate deal that could plausibly lead to a geopolitical broader understanding? That is how geo-economics can be pushed further.

Remaining obsessed with blame-game and playing to the gallery hasn’t worked to this day. Time for India and Pakistan to get real, and look at the bigger picture of collective betterment.

Not sure what motivated the 15th century world-acclaimed Italian painter Leonardo di da Vinci to say, “Water is the driving force of all Nature.” But yes, it is so, and perpetually fits the Indus Basin future. Let’s unite for water and browbeat turbulence.