So tell the tale — perhaps they will reflect. [Koran 7:176]

The Shariah

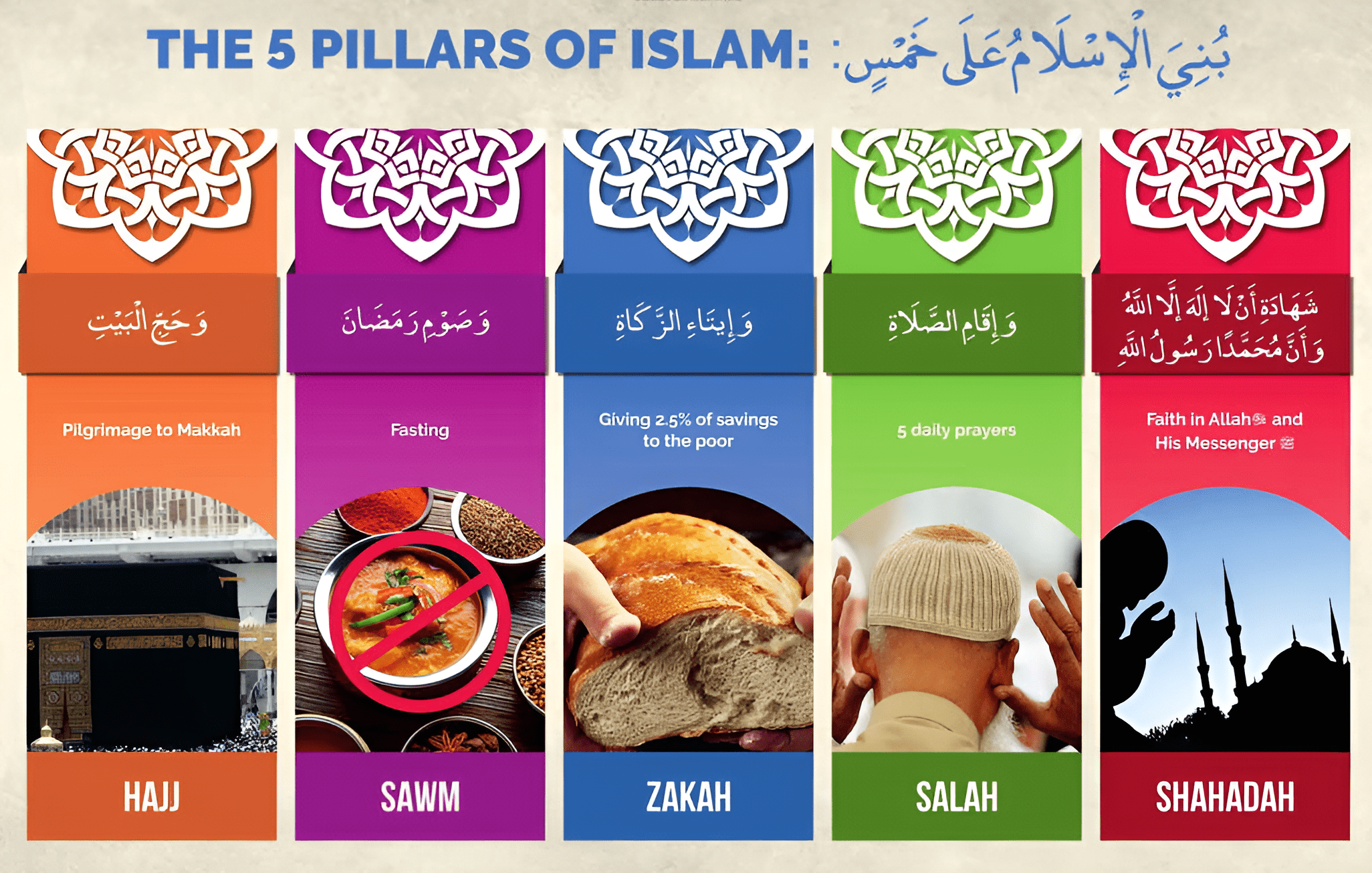

The Five Pillars are the basic practices of Islam. They are relevant to every Muslim, though it may happen that many people never have to pay zakat or do not make the Hajj because their personal circumstances make it impossible for them to do so. But all Muslims have uttered the Shahadah because that is what makes them Muslims. The Salat is incumbent upon all adults every day, although women are excused during certain times of the month. Fasting during Ramadan is also an annual practice for everyone, though there are several valid reasons for not observing it.

There are many other Koranic and prophetic injunctions that Muslims have to observe. Many of these pertain to moral prescriptions and have a universal applicability. Among forbidden activities are lying, stealing, murder, adultery, and fornication. Other injunctions relate to domains that in modern Western usage are usually considered to lie outside the pale of religion, such as inheritance, marriage, business transactions, and foods that may or may not be eaten.

The whole body of rules and regulations set down by the Koran and the Prophet gradually came to be codified as the Shariah, or “the broad path leading to water,” the road of right activity that all Muslims have to follow. The water here is the heavenly water that purifies and saves, a water that is alluded to in many Koranic verses:

He sends down on you water from heaven, to purify you thereby, and to put away from you the defilement of Satan. (8:11)

The term Shariah is often translated as “Islamic law” or “revealed law.” The study of this domain of Islamic learning is called fiqh (jurisprudence). The specialists in this kind of learning are the fuqaha’ (jurists) to whom we have already referred. Practically all ulama—all Muslims learned in Islam—have a wide knowledge of jurisprudence, but some of them have specialized in other areas, such as theology, philosophy, or Sufism. As already indicated, the vast majority of those who are recognized as ulama in Islamic countries— the mullahs as they are called in many places—are in fact jurists, since they have little or no learning in other domains. This is to say that knowledge of Islam’s first dimension is required of all Muslims, but knowledge of the second and third dimensions, though in many ways as important, is much less widely disseminated.

The primary importance of activity in the Islamic view of things appears completely natural to Muslims. After all, everyone must be involved with activity because of the human body, and hence everyone has need of guidelines for doing things. Of course it is also true that everyone has a mind and a heart, but it is in the nature of things—at least in the historical eras of which we have knowledge—that most people do not get involved with too much thinking, nor do many people devote themselves to purifying their hearts and their intentions in order to prepare themselves for the vision of God. These endeavors have always been the domain of a minority, and Islam is no exception.

One of the reasons that the word law is not quite appropriate to refer to everything dealt with in the Shariah is the connotations of the English word. To begin with, we think of law as commands and prohibitions. For example, the law tells you that you have to pay taxes and that you are not allowed to commit murder. At the same time, there is a third category of human activities, the category of things that are not regulated by law.

Islamic jurisprudence deals with these same three categories, but it adds two more domains that it considers important. Not only does the Shariah tell people what they must do and what they must not do, it also tells them what they should do and what they should not do, and it tells them explicitly that many things are indifferent. Hence we are faced with five categories of actions: the required, the recommended, the indifferent, the reprehensible, and the forbidden.

As a result of this way of looking at things, the Shariah covers a great deal of ground that in modern terms seems to belong outside a legal system. As an example, let us take a look at the category of “recommended.” As we have seen, the Five Pillars are all required. But in addition to the five required salats, there are a large number of recommended salats. For example, it is recommended that, before saying the two cycles of the morning prayer, people should perform two other cycles. Each of the daily prayers has a certain number of recommended cycles that accompany it.

In the case of fasting, people are required to fast only during Ramadan. But it is recommended that they fast during certain other days of the year, certain days of each month, and even certain days of each week. Likewise, those who pay the zakat are not required to give more than a certain amount of their profit, but it is recommended that they give away much more. It is also recommended to make loans—without interest, since interest (according to most opinions) is forbidden. Some authorities maintain that lending money is more meritorious than giving it away, because the person who borrows the money has a moral obligation to pay it back, and thus he or she is encouraged to find steady employment. And when the money is paid back, it can be loaned to someone else, thus doing more good work.

The fifth pillar also has a recommended form, which is a pilgrimage to the House of God outside the season of the hajj, a ritual called the umra. People should make the umra if they have the opportunity. And since it is a recommended act, it needs to be described in all its details in the textbooks on the Shariah.

Many things are considered reprehensible, such as divorce, using more water than is necessary while making an ablution, scratching oneself while making the salat, and eating until one is satiated.

The attention that the Shariah pays to food often appears strange to Christians (in contrast to Jews). Muslims are forbidden to consume intoxicating beverages and narcotics. They are also forbidden to eat pig, dog, domestic donkey, and carrion, which is defined as the meat of any animal that has not been ritually slaughtered. Animals are slaughtered ritually by cutting their throats while mentioning the name of God. This ritually slaughtered meat is then called halal (permitted). Many jurists maintain that meat prepared by Jews or Christians is halal for Muslims, while others disagree. On this point the Koran gives a general ruling: “The food of the People of the Book [those who have been given scriptures, such as Jews and Christians] is permitted to you” (5:5), although it is understood that this food, if meat, must be slaughtered in the name of God. Kosher meats in particular seem to fit this category. In general, the Shariah declares that it is forbidden to eat any wild animal that has claws, nails, or tusks with which it overcomes its prey or its enemies, such as lion, tiger, wolf, bear, elephant, monkey, and cat. However, one school of law maintains that it is reprehensible to eat these animals, not forbidden.

Minor differences of opinion among the jurists are quite common. Thus, most of them maintain that all animals that live in the sea are permitted, whereas one school makes an exception for sea animals that do not take the form of fish—such as shellfish, crabs, alligators, or walruses. Because of the existence of five categories instead of three, Islamic law goes into all sorts of details about everyday life that would not otherwise be discussed. It has many branches and subfields, expertise in which can require years of study. Many Muslims accord so much importance to the Shariah that it seems to become for them the whole of their religion, at least in practice. Nevertheless, many of the greatest Muslim authorities have warned against spending too much time studying the Shariah, since this can blind people to the other dimensions of the religion, which are also essential to Islam.

Al-Ghazali (d. 505/1111), one of the most famous of the great authorities, held that each Muslim must have enough knowledge of the Shariah to put it into practice in his or her own life. But if Muslims do not need a given injunction in their circumstances, they have no need to know about it. There will be, in any case, people who devote their lives to the study of the Shariah, and they can be consulted when the need arises. This explains the basic function of the jurists in society: to explain the details of the Shariah to those who need to observe it in any given circumstances.

To take a simple example, when a youngster wants to learn how to say the salat, the normal route is to ask a family member how to do it. There is no need to consult books, since most people are familiar with the basic rules, but it may happen that one person says you hold your hands this way, and another says you hold your hands that way. What do you do? Of course you ask someone else. Soon, by asking, you will reach the imam (prayer leader) of the local mosque, who is normally the most knowledgeable person about these things. But the imam may not be an expert in jurisprudence, and if the question is good enough, he may send you to a jurist, who will then explain the details. Not that this is necessarily the last word. There are other jurists, and jurists, like scholars everywhere, have differences of opinion. Basically, it is your duty to keep on asking until you are satisfied with the answer.

Sin

The Shariah sets down rules for right activity. These are God’s rules as specified in the Koran and explained by the Prophet. The Koran and the Hadith are the two basic sources of the Shariah. If the ulama consult these sources and a question still remains, they can consult the opinions of the great Muslims, the recognized authorities in the Shariah. Hence consensus (ijma) is recognized as a third source of Shariite rulings; Sunnis consider reasoning by analogy (qiyas) a fourth source, while Shi’ites put reason (aql) in its place.

If people accept the instructions of God as set down in the Shariah and put them into practice, this is called “obedience” (taa). A correct act is an obedient act. God or his Prophet say, “Do this” or “Don’t do that,” and a good Muslim obeys these instructions. The Koran frequently employs the word obey to refer to right activity:

Obey God and the Messenger; perhaps you will be shown mercy. (3:132)

Obey God and obey the Messenger, and beware. But if you turn your backs, then know it is only for Our Messenger to deliver the clear message. (5:92)

Whoso obeys God and His Messenger, He will admit him to gardens through which rivers flow, therein dwelling forever. (48:17)

Whosoever obeys God and the Messenger—they are with those whom God has blessed. (4:69)

It is not for any man or woman of faith, when God and His Messenger have decreed something, to have a choice in the matter. Whosoever disobeys God and His Messenger has been misguided with a clear misguidance. (33:36)

If obedience is right activity, then disobedience (masiya) is wrong activity. Human disobedience began with Adam, who ate the forbidden fruit. “Adam disobeyed his Lord and went astray” (20:121). Disobedience is the attribute of anyone who fails to obey God and his messengers. The Shariah codifies the instructions of God and the Prophet, so disobedience to the Shariah is considered disobedience to God. This is one of the meanings understood from the following verse, where “the possessors of the command” can be interpreted to mean those who have the requisite learning to explain the Shariah to Muslims:

O you who have faith! Obey God, and obey the Messenger and the possessors of the command among you. If you should quarrel on anything, refer it to God and the Messenger. (4:59)

The Koran uses the verb to disobey in several verses, almost always in discussion of the reaction of the wrongdoers to past prophets. But the underlying message for Muslims is clear:

These are God’s bounds. Whoso obeys God and His Messenger, him He will admit to gardens through which rivers flow, therein dwelling forever; that is the mighty triumph. But whoso disobeys God and His Messenger, him He will admit to a Fire, therein dwelling forever, and for him awaits a humbling chastisement. (4:13-14)

Scholars writing on Islam frequently translate ma`siya as “sin,” and of course this word does mean sin in a general sort of way. But disobedience is a special kind of sin, one that is defined in terms of God’s commands and prohibitions; and it always calls to mind its opposite, which is obedience. The Koran uses several other words that are commonly translated as sin, including, among others, dhanb, ithm and khati’a. Each of these terms has nuances that differentiate it from the others. All this is to say that the English word sin is, from the Islamic point of view, extremely vague, since it encompasses several types of activity. What all these terms have in common is that talk of sin involves judgments about activity, and this is the domain of the Shariah. The Shariah cannot ignore the issue of intentions, but it deals with them almost exclusively in relation to acts. Those of the ulama who look at intentions from the perspective of Islam’s third dimension have a far broader view of the deep moral and spiritual issues that are involved in sin.

It would be appropriate to round out this discussion of disobedience and sin with a discussion of the general Koranic view on the good works that people perform in order to be obedient. However, we will leave this discussion for Part III of this book. At that point we will have enough background to relate good works to all three dimensions of Islam. For the time being, we will simply say that the most common term that the Koran employs for good works is salihat, which can be translated as “wholesome deeds.” Those who perform these deeds are often called al-salihun (the wholesome). When the Koran and the Islamic tradition mention wholesome deeds, what is meant is activity that represents obedience to God’s command. The primary wholesome deeds are the Five Pillars, but every sort of good deed is included in the category, that is, all those deeds that the Shariah recognizes as good. In addition, the authorities of the second and third dimensions of Islam often broaden the term to include a wider definition of good.

The Historical Embodiment of Islam

The ulama are those who have knowledge of the religion. By this definition, the most knowledgeable person is God Himself, and indeed, one of His names is al-`alim, the Knowing. Among human beings, the Prophet Muhammad (Pbuh) is considered to have had more knowledge than anyone else, and he himself said, “I came to know everything in the heavens and the earth.” Naturally, the primary teachers of the Shariah are God and the Prophet—as represented by the Koran and the Hadith.

The Koran and the Sunnah

The role of the Prophet in codifying Muslim learning should not be underestimated. In principle, everything is in the Koran. But actually, an enormous number of details concerning Islamic practice can be found only in the Hadith. For example, the Koran repeatedly commands people to perform the salat, and one can probably understand from various verses that this performance involves standing, bowing, prostrating oneself, and sitting. Likewise, the Koran makes it clear that people need to be pure before they perform the salat. But nowhere does the Koran provide precise instructions on how to perform the prayers or make the ablutions[1]. Here the Sunnah—the exemplary practice—of the Prophet becomes absolutely essential for the religion. The Sunnah in turn is recorded in the Hadith[2]. It is the Prophet who told people that they should stand, bow, and prostrate themselves in such and such a manner and while reciting such and such Koranic verses or words of praise and thanksgiving.

Many of those who were especially close to the Prophet played an extremely important role in the transmission and dissemination of Islamic learning. They heard what the Prophet said on various occasions, or they saw what he did, and later they reported his words or described his actions to others. Among the most important of these companions were his wife, A’isha, and his cousin and son-in-law, Ali. The reports of hundreds of the Prophet’s companions are recorded in the books on Hadith[3].

Islam is fundamentally a practice, a way of life, a pattern for establishing harmony with God and his creation. Just as islam signifies, in its most universal meaning, the submission of all things to the divine wisdom and command, so also in its more specific, human senses, it signifies the proper functioning of the human being and human society through submission to the divine pattern. This pattern for right life is manifested first and foremost in doing. It is true that doing depends upon knowing and willing, on choices differentiated and courses of activity consciously followed, but that is another issue—which will be discussed in its own place. For now we want to stress the fact that the criterion for being a Muslim is fundamentally the outward activity that people perform.

Hence, to be a good Muslim means following the Sunnah of the Prophet—doing things in the way that Muhammad (Pbuh) did them. The most important thing that Muhammad (Pbuh) did was to receive the Koran from God, thereby establishing the religion of Islam. His followers cannot receive the Koran directly from God, but they can receive it indirectly from him through the Prophet’s intermediary. They receive it by learning it, memorizing it, and reciting it.

Memorization of the Koran is considered one of the most beneficial religious acts, and, as we have seen, it provides the basis for traditional Islamic education. All Muslims memorize at least some of the Koran, because without knowing the Fatihah and certain other verses, they cannot recite the salat. The salat itself is the daily renewal of the Koran in the Muslim. It is the first and primary embodiment of the Koranic revelation in human existence.

Given the foundational nature of activity for human existence, it is not surprising that Muslims look first to activity in judging the extent to which Islam is observed. Historically, what is certain is that the fundamental activities go back to the prophetic period, and that Muslims have always been extremely attentive to what exactly should be done in every circumstance. They observed the Prophet (Pbuh) carefully, and they listened to him attentively, and they put what they had learned into practice in their own lives. The Shariah was later elaborated and codified on the basis of what pious and sincere Muslims were doing. And these people traced the pattern for their own activities back to the Prophet’s Sunnah.

We will not go into the historical details of how exactly Islamic practice was passed down among the early generations of Muslims. These things are not known for certain, and modern historians have expended a good deal of effort in trying to map this out, without too much success[4]. But we can summarize the net result of the transmission of the Sunnah—the birth of several recognized ways of observing the Shariah.

The Madhhabs

As the years and centuries passed, the living memory of Muhammad (Pbuh) and his Sunnah gradually weakened, and it became more and more necessary to record the details of his life and practice so that they would not be lost. At the same time, the areas within which Islam became established continued to go through the vicissitudes that mark human existence—the differences of opinion, the struggles for power, the loves and hates, the natural and man-made catastrophes. In other words, history went along as usual, but now the Koran and the Sunnah of the Prophet (Pbuh) became added factors in human relationships.

The picture of those times was the picture of all times. Ali summed up the reports of all the historians to come when he said, “Time is two days: A day for you, and a day against you.” But he did not leave it at that. Following the example of the Koran, which deals with historical events only insofar as they teach something about the human relationship with God, he reminded people of two of the primary virtues that need to be cultivated: “When time is for you, give thanks to God, and when it is against you, have patience.”

At the beginning of Islam, observing the Sunnah of the Prophet was part and parcel of being a Muslim, and one learned it by following the example of those who were Muslims before. This explains the sense of such prophetic sayings as the following: “My companions are like stars. Whichever you follow, you will be guided.” After the companions came the “followers,” those who had met the companions. As long as Islam was a relatively small community in which faith and practice remained intense, it was perfectly feasible for people to be good Muslims by following the example of their companions and teachers. But gradually the community—as religious community, rooted in Islam’s three dimensions—became dissipated, especially when the early conquests brought enormous wealth. Many Muslims lost sight of the original goals of the religion and became caught up with other activities. At this point religious learning became more and more the domain of a limited number of people, and they found it feasible to pass on their learning only to a relatively small number of students and perhaps to write a book or two to preserve some of the essentials of knowledge.

Knowledge of the Sunnah, in short, gradually became a specialized field of learning. Moreover, as the community expanded, the vicissitudes of life and fortune meant that Muslims came face to face with all sorts of human experience that had to be sorted out. The idea that islam is the attribute of right activity and embraces the whole of creation meant that nothing could be ignored by those who were trying to put the Sunnah into practice.

But what did people do when they met a situation that never arose during the Prophet’s lifetime? Or, from another direction altogether, what did they do when they met two or more contradictory reports about the Prophet’s activity? How did they decide which report was correct?[5] Issues such as these gradually led to the formation of a number of different “trodden paths,” each representing a slightly different understanding of what exactly the Sunnah of the Prophet was and how it could be applied to human life. We say “slightly different” from a modern perspective. Within the context of the times, the differences often appeared major, and on occasion conflicting views could lead to pitched battles (although this is true only if various social and political factors were mixed into the brew). At first there were scores of these paths, each focused on the teachings of someone thoroughly knowledgeable in the Sunnah. Gradually some of the ways disappeared or became consolidated with others. Eventually four paths became recognized among Sunnis as equally valid. Muslims could follow any path they chose, and it has not been uncommon for them to combine the paths, following one on one issue and another on some other issue.

The word that came to be employed for the different versions of the Prophet’s Sunnah was madhhab, which derives from a root meaning “to go.” A madhhab is a way of going, a route, a road that is walked, a trodden path. It is sometimes translated as “school of law” or “school of jurisprudence.” Each correct way of practicing Islam is a way of walking in the Sunnah. Each represents one way of interpreting and applying the Shariah.

The four madhhabs of Sunni Islam are named after those who are looked back upon as their founders, the ones who took the most important steps in codifying the rules and regulations of the madhhab and differentiating it from other ways of interpreting the Sunnah. The four founders are Abu Hanifa (d. 150/767), Malik ibn Anas (d. 179/795), al-Shafii (d. 204/820), and Ibn Hanbal (d. 241/855). Most Shi’ites follow a fifth madhhab named after the sixth Imam, Jafar al-Sadiq (d. 148/765), who was, incidentally, one of the teachers of Abu Hanifa.

There are no major differences separating the madhhabs, at least not from the external perspective that we naturally have to take. A non-Muslim unfamiliar with the Shariah would find it extremely difficult to see any difference, for example, between the way two Muslims who follow two different madhhabs perform the salat. But specialists in jurisprudence can point out tiny differences in practically every stage of the ritual. The different schools very often agree on certain points, while differing on others. Jafari or Shi’ite law is no different here, and it tends to be especially close to the Hanafi position. However, there are two specific instances where Jafari law establishes minor practices that set it apart from the four Sunni schools. The first is the permissibility of a form of temporary marriage (muta), and the second is in the establishment of a specific form of alms-tax (the khums), which is the share of the Imam. Although there were many madhhabs in early times, eventually all Sunni Muslims came to observe one of the four just mentioned. Once these became established as the right ways, no major changes in the Shariah took place. So much is this true that it has often been said that the “gate of effort” in determining the rulings of the Shariah was closed. Many of the great ulama, however, took no notice of this opinion and continued to exert effort as they saw fit. As for the Shiites, they reject this opinion absolutely, saying that the “gate of effort” is always open and that it is forbidden to follow the juridical rulings of someone who is dead.

Early Western scholarship on Islam tended to make a big point of this closing of the gate of effort, often with the intention of criticizing Islam for an alleged stultification of legal thinking. Scholars often like to suggest that modern people like themselves are very smart and dynamic, while people in olden times were rather dull and unimaginative. More recent scholarship has become aware of the self-congratulation implicit in many earlier judgments of non-Western cultures and has begun to reevaluate the sources. As a result, it has been shown that in the case of Islamic juridical thinking, a great deal has been going on in many areas, especially when it has been a question of new situations—situations that naturally occur because of historical change. Where the judgment about closure is more or less valid, however, is in the area of the Five Pillars, the fundamental acts established by the Sunnah.

Jurisprudence and Politics

The jurists are those ulama who specialize in the Shariah. Each jurist is typically a specialist in one madhhab, although some may be familiar with other madhhabs as well. In a certain Christian and post-Christian way of looking at things, jurisprudence appears to have no relevance to what today is often called “spirituality.” There is a certain truth in this judgment and many Muslim authorities over the centuries have made the same point. After all, the jurists are very careful about looking at all the details of activity, and typically they drone on and on in the manner of lawyers. Jurisprudence is a science that revels in nit-picking. Although it is a necessary science in Islam, if too much stress is placed upon it, it can discourage the attention that should be paid to Islam’s second and third dimensions.

Like modern lawyers, many of Islam’s legal authorities were intensely interested in and involved with political affairs. The Shariah, after all, sets down many rules and regulations that have a general social relevance, especially the teachings on transactions and contracts. In addition, the Koran says a great deal about the importance of justice and honesty in human relationships. It establishes concrete rules for redistribution of wealth through zakat and encourages other forms of charity.

There is no doubt that the Koran and the Prophet (Pbuh) provided guidelines for society and that these have been put into effect with some success throughout Islamic history. But neither the Koran nor the Hadith is explicit on methods of government. Some of the early Muslim philosophers proposed political theories, but these were never influential in practice. What occurred in Islamic history is that the institutions of the time, which were basically monarchical, continued to function as before. The Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates ruled ostensibly as Islamic governments, but they were hereditary monarchies nonetheless. Since the Caliphs appealed to Islam for their legitimacy, they were forced to acknowledge the Shariah as the law of the community. Some of them also observed the Shariah carefully in their own lives, and, by most accounts, many of them did not. For the majority of Muslims, however, kings and Caliphs retained their legitimacy so long as they did not reject the Shariah in public.

It is commonly said that Islam does not exclude government from the realm of the sacred. This is true. Islam does not exclude anything under the sun from the realm of the sacred, but this does not mean that every government in Islamic history has been a government run by sincere Muslims intent upon observing the Shariah. Kings tend to be worldly people, as do those who become involved with government in general. Muslims have always recognized that government should put the Shariah into practice and be run by good Muslims, but they have also recognized that this has been the exception rather than the rule. Some Muslims would claim that the last example of a good Muslim ruling the community is provided by the fourth caliph, Ali, and from the time of the Umayyads to the present, the extent to which government has heeded Islamic teachings has steadily decreased. Today’s Islamic republics are no exception to this general rule.

By and large, religion has simply become the latest tool of those who crave power. Many Islamic authorities have criticized the jurists for their tendency to congregate in centers of power. The jurists always have something to say about government policies. In many cases, they are simply doing their duty, which is to try to provide guidance as to how the Shariah can be properly observed, but like lawyers everywhere, the jurists know how to manipulate the law for their own ends, and there have always been jurists who would sell their skills to the powers that be. Every king has had an official mullah or two who was willing to issue whatever “Islamic” edicts were necessary for the government to function in the way that the king desired.

In the modern world, Muslim scholars have devoted an extraordinary amount of attention to theories of government and political science, often in the attempt to make Islam fit the mold of “democracy” dictated by Western models (and remember that Marxism has always presented itself as the best form of democracy). There is no lack of books on politics in the Islamic context, and readers who are interested can consult any decent library.

In our view of things, politics was never a very important issue for the vast majority of Muslims throughout history. Many Muslim thinkers were intensely interested in establishing social harmony and equilibrium on the basis of the Shariah, but they did not see this as something that should be or could be instituted from above. People had to conform themselves to the Shariah and the other dimensions of the religion. If they did so, society would function harmoniously.

The Koran repeatedly commands “bidding to honor and forbidding dishonor,” and this has always been taken as a command to take a certain responsibility for one’s social surroundings. But this is one of many commands, and other commands take precedence. It is difficult to read this as meaning that God has now empowered a few politicians to take control and put into effect policies that “society needs.”

The ideal of Islamic life has always been organic rather than mechanical. The best way to gain a feeling for this is simply to look at the physical structure of traditional Islamic cities, which are reminiscent of luxuriant jungle growth. The modern ideal is rather the grid, a “rational” order imposed from outside. In many parts of the Islamic world, the secularizing governments have imposed the grid on the old city. One of the aims has been, of course, to destroy the traditional social structure so that it can be remade in the image of the industrialized West. So also, modern Muslim political thinkers have been attempting to rationalize the traditional teachings on government and society with specific social goals in view[6]. We will suggest, when we discuss the last part of the hadith of Gabriel, why this excessive stress upon a specific kind of modern rationality is simply aiding in the dissolution of Islamic values and the Islamic world view.

To be continued ……

Reference / Links[7]

[1] Notes added for further reference & study:

O ye who believe! when ye prepare for prayer, wash your faces, and your hands (and arms) to the elbows; Rub your heads (with water); and your feet to the ankles. If ye are in a state of ceremonial impurity, bathe your whole body. But if ye are ill, or on a journey, or one of you cometh from offices of nature, or ye have been in contact with women, and ye find no water, then take for yourselves clean sand or earth, and rub therewith your faces and hands, Allah doth not wish to place you in a difficulty, but to make you clean, and to complete His favour to you, that ye may be grateful. [ Al-Ma’ida, Sura 5, Ayah 6] https://trueorators.com/quran-tafseer/6/116

[2] Hadith and Sunnah: https://wp.me/pcyQCZ-46

[3] https://bit.ly/ReviseHadiths

[4] https://wp.me/scyQCZ-index

[5] http://bit.ly/UmerNhadiths

[6] https://bit.ly/IslamicDemocracy

[7] http://bit.ly/3IWFAFi