Nizam-e-Maikada Bigra Hua Hai Is Kadar Saqi;

Usi Ko Jaam Milta Hai Jise Peena Nahi Aata

(Anand Narayan Mulla) [The configuration is so disfigured that only those who do not possesses a remedy are accessed with it)

Ten cents for the poet, as it navigates the truth in case of Pakistan-Afghanistan relations all these decades. It was a faux pas moment for Pakistan’s security forces on November 13. The Friendship Gate at Chaman border witnessed a bloodbath, as a security personnel was gunned down by an Afghan shooter. The incident led to maiming of many others, but surprisingly enough the fire was not retaliated from Pakistan’s side. Irrespective of the fact that the Taliban promised to probe into the fissure, and till then Islamabad vowed to keep the border shut, but for reasons best known to none, Pakistan reopened the frontier for trafficking as the militia kept on drifting here and there.

Afghanistan is an enigma for Pakistan. It has been at odds with it during the last seven decades, irrespective of whether Kabul had a pro-Pakistan government, or otherwise. Pakistan’s so-called obsession of Strategic Depth, a term coined by the then Army Chief Mirza Aslam Baig, while addressing his soldiers on August 25, 1988, has rendered more problems than any solution.

The fear that in case of an Indian ingress over Pakistani soil, the western flank will serve as a friendly retreat had earned flak. Indeed, it was a defeatist concept of withdrawal. Pakistan’s impregnable armed forces never realized that moment, and shall never, but geo-strategically Pakistan had lost its prestige and ground to successive ungrateful dispensations in Kabul.

Pakistan, as it gears up with its new doctrine of geo-economics should thematically work with Afghanistan. It must turn a new leaf and stop looking at it from the prisms of India and the United States.

The first and foremost concern should be to address the trust deficit that has impeded progress, and even the Taliban 2.0 government has been a non-starter. It is a moment of some deep introspection, and cannot be absolved by pointing a finger at Delhi or Washington.

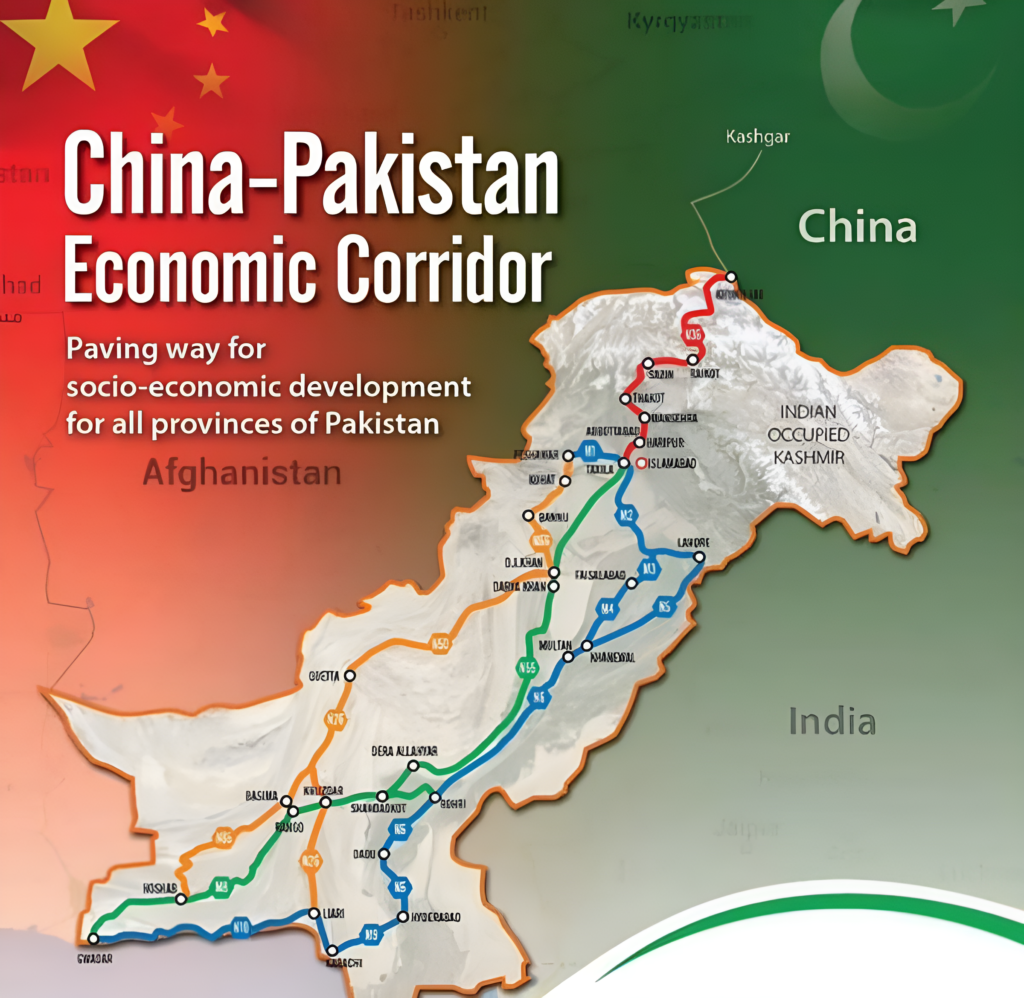

Seriousness of thought is indispensable if the concept of connectivity has to take roots. The staggering $60 billion CPEC investment is hostage to discord between Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as an unending rivalry with India.

So is the case with Gwadar Port, which crosses swords with Iranian Chahbahar Port. One has to be mindful that Iran and China have a 25-year long $400 billion understanding, and Beijing is eyeing Afghanistan as its next cathedral for investment. In such a scenario, Afghanistan being at odds with Pakistan in the security and socio-political realms is a misnomer, and bodes extreme ill-will.

The fact is that the porous borders with Afghanistan are one of the most corrupt in the world. No amount of regulations has been a success, and it goes without saying that men manning it on both sides of the divide, and the authoritarian gurus sitting back in their comfort zones elsewhere are compromised, and this has led to devastating consequences not only in the economic milieu, but also political and security domains.

The abject terrorism unleashed on both sides of the frontier, and the undeniable truth that the world’s most dangerous terror hub was Afghanistan since 1979 is a case in point. This is merely because of a lack of policy approach that is ingrained in realities of the land, and superficial efforts on the part of respective rulers to further their own eras at the cost of collective prosperity.

A referral from history is worth a point here. Former Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in his hallmark book ‘If I am assassinated,’ wrote that an agreement with Mohammed Daoud Khan, the man who overthrew the monarchy and became the first President of Afghanistan, was done wherein the Pashtunistan and Durand Line issues were addressed. But the same could not see the light of the day.

So is the case with many such accords that were penned with Kabul, but are gathering dust in the annals of archives. Exigency, proximity and fear of the unknown had prevailed, and even the Mujahideen who were under the belt of Pakistan’s military establishment had played havoc.

One more aspect, though less discussed, is the abject civil-military discord over Afghan policy. For long the call has rested with the General Headquarters, and literally not the Foreign Office.

This is because of the strategic importance that the western neighbour possesses, and likewise the upper hand of expertise, surveillance and the micro-management that the army can conveniently ensure over civilian authority. An instant outcome has been that Soviets and Americans were shunted out of Afghanistan, and Islamabad held the decisive word come-what-may. The first-ever bloodless exit of the United States from Afghanistan in the wake of Taliban’s take care is recent history.

Despite so much articulation, Pakistan once again flunked as it could not carry the baton with the Taliban. It was an ideal moment for Islamabad to strike a chord of consensus with the student militia, which had played to its tune during all its years of wilderness since the Tora Bora bombardment.

The Doha Accord in 2020, wherein Taliban signed on the dotted lines with the United States was all owing to Pakistan’s persuasion and state of art diplomacy. But when the Taliban rode victorious in Kabul on August 15, 2021, to the surprise of all, Pakistan looked the other way around.

Pakistan’s refusal to recognize the Taliban was ill-calculated. Apparently for reasons of diplomatic exigency, it wanted a broad-based consensus to make a stride in that direction. The moment slipped, and Islamabad is now left high and dry.

The Taliban are no more in the influence of Islamabad. They have seen the world at large as they went through trial and tribulations for almost two decades since 9/11, 2001.

The fact that they have ruled the multi-ethnic state without an inclusive government for more than a year, and were able to pass a deficit-free budget despite their assets frozen to the tune of $9 billion by the international lenders and Washington has made them a perpetual reality. Last but not least, they are confidently talking to the Chinese, Russians, Saudis and the Americans too, and have learnt the art of agreeing to disagree.

The capitulation in the backdrop of a politic-security agreement with the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (on the run in Afghanistan) and their softies inside Pakistan speaks volumes of our overstretching. Pakistan has experienced a spike in militant attacks, and horrifying statistics put the toll over 450 people, mostly security forces in the first nine months of this year.

The uprooting of fences by Taliban and their refusal to acknowledge the Durand Line are unending fissures. It goes to the resilience of Pakistan’s security forces that they have successfully fenced the porous almost 2600 kilometres long border. It will widely help in checking smuggling of men and material, and buoy the prospects of institutionalizing CPEC, as Afghanistan is a desired entity in the long-run.

The million-dollar question in such a scenario is where does Pakistan stand? Has Islamabad obliterated its image, prestige and locus standi? Is it getting isolated, or what? No qualified answers, either!

Pakistan has to undertake some instant quick-fix steps.

The first is to reorient its psyche vis-à-vis Afghanistan. It must start looking inward and stop bothering about Afghan internal order. That is not our lookout. All previous efforts to foment a political narrative for Afghans had backfired, and we had our fingers burnt.

Pakistan should bear in mind that the West has lost interest in Southwest Asia, especially since a crisis has erupted in Eurasia. The war in Ukraine and the Russian aggression has pitched the US in a proactive role elsewhere, and South Asia is none of its business. Thus, hoping hip-hop diplomacy on Afghanistan and trying to cash on the upheavals is a business of the past.

Washington perpetually has strings to keep a check on China, and India and the QUAD amalgamation are well in place. With focus now once again on the Mideast, the Biden administration has less to care for Afghanistan.

The pooling up of American assets in Central Asia for espionage and aerial operations inside Afghanistan has put Pakistan to the wall. The taking out of Ayman Al Zawahiri, the second-in-command of Al Qaeda, is a testimony of its outreaching.

A couple of recommendations can be mooted so that the neighbouring discord is shelved, and the earliest the better:

• Create stakes of Afghanistan in Pakistan so that the bad blood is diluted. The same applies to India.

• Rewrite a new social contract with the tribal people of Pakistan, and stop screening them on the basis of linguicism.

• Start treating Afghanistan as a sovereign and independent state. The mindset of it being the backwaters of Pakistan is irrational.

• Put the border issue on the backburner and get into an extensive cultural and political orientation with the Afghans by making use of cross-border activism in a positive sense.

• Streamline trade: there is a sound possibility of $5billion trade which is lacking at the moment and is in Afghan favour.

• Stop instantly worrying for a friendly government in Kabul.

• Float Investment Visa for Afghans. It is noticed that affluent Afghans go and invest in the UAE. Why can’t they be welcomed in Pakistan?

• A quadruple dialogue is the need of the hour between Pakistan, Afghanistan, China and India. It will be a win-win equation for all, and will reset the region’s campus in all prosperity.

It is high time to put a full stop to the gangrene that is bleeding Pakistan from its western frontiers. It has maimed its entire body politick, and devastated its social fabric. Gun culture, drugs, sleeping cells, pestering uncertainty, refugees’ influx and regional chaos are salient features of our blunders with the restive landlocked state. Though none remorse it to this day, especially the policy-makers who were beneficiaries, the nation is paying the heavy toil.