The current global order has witnessed a pragmatic shift with the rise of China through the notion of economic power. On account to this, maintaining constructive relationships with its neighboring countries has become a principle strategy for its economic development and promotion of foreign trade.Geographically, China shares a common border with four (Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan) out of seven South Asian states (the other three are Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives), giving it an integral leverage in the regional socio-political and economic affairs.Beyond its rapid economic growth, China, through advertising its core values and publicizing its culture, emerged as a potential competitor to the United States in the Asian region, particularly after the liberalization of its economy. Thus, the notion of economic power became imperative for Beijing’s rise through an effective utility of various means. Such Chinese investment along the Indian Ocean littoral gave genesis to the notion of ‘string of pearls’ to elucidate China’s presence in Bangladesh, Burma, Sri Lanka and Pakistan as largely strategic.India too has played a key role in investing in the South Asian nations. In 2017, Bangladesh’s Prime Minister received $9 billion from India. India also invested $70 million in satellite setups for fostering telecommunications, early flood warnings and weather forecasting to itself and Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Maldives and Bhutan.

Generally, the very concept of ‘power’, regardless of its wide manifestation, lacks understanding. Therefore, power within international relations usually lacks an unanimous agreement. Many have approached it through their own perspectives and thus a distinction can be seen in the available literature. Economic power is a relatively recent phenomenon which fits well in the 21st century dynamics as globalization and an ‘information age’ has ascended. The liberal scholar Joseph S. Nye deemed as the pioneer of this theoretical concept defined soft power as ‘the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments. It arises from the attractiveness of a country’s culture, political ideals, and policies.’ By the start of the 19th century, China stood tall as possessing one third of global GDP.Till the 18th century, China stood at par with Europe in terms of its GDP per capita. Although the 20th century witnessed a decline thereof but recently, China has managed to emerge as the world’s second largest economy after US, the global superpower and today it stands with the world’s third largest trade volume (after the US and Germany) and thus retains a sacred place for global FDIs. According to The World Bank, in 2017 China’s GDP was $12.238 trillion, only second to the US (at $19. trillion). Massive material and societal level developments have occurred in China which have added to its economic power potential.

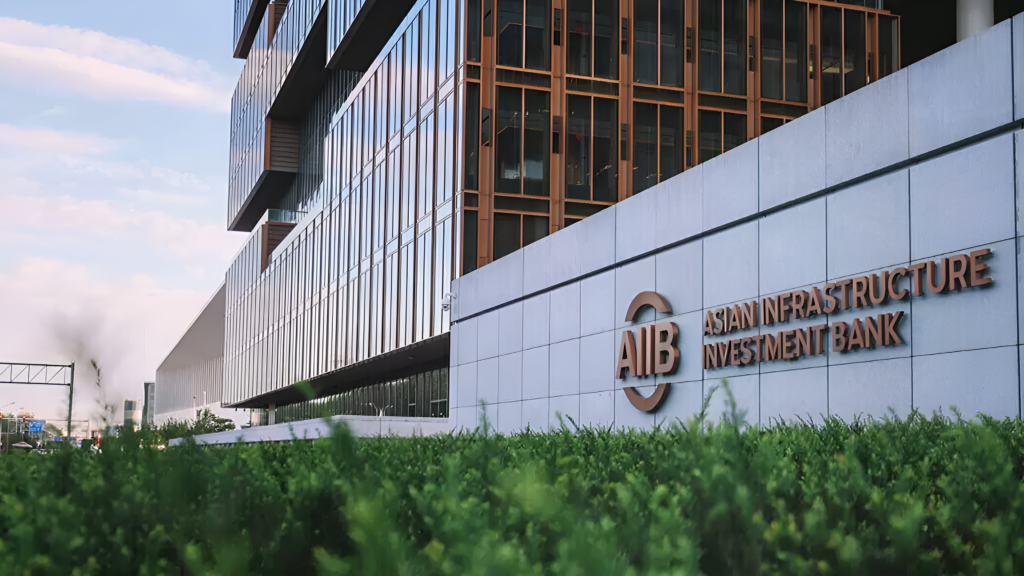

China developed new ventures such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the BRICS Bank and the OBOR initiative in order to meet its changing growth imperatives. China extended its soft power in this region making inroads by stating that economics is the primary objective of the OBOR initiative. It will connect six countries through an extended network of roads, pipelines, railways, fibre optics etc. The vertex point of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy consists of the OBOR which reflects China’s ascendance in the world in terms of economy, politics and strategy. China also established the Asian Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) in order to assist and develop regional infrastructure improvements via technical services and injecting capital through loans. China’s genesis of the AIIB as the first Chinese multinational financial institution contains great scope for soft power influence.

China has largely used a benign rhetoric for its Belt and Road initiative and its maritime economic belt. Although seemingly it has been economic in nature, India reserves its apprehensions in this regard. Delhi has traditionally sought to maintain dominance over its own region by which the geographical location allows it to extend political leverage, as it shares borders with all South Asian states, with the exception of Afghanistan.

However, contrary to its aspirations, Indian policies were inclined towards hard power with respect to most of its neighbouring states. For instance, it engaged in wars with Pakistan; its crisis of 1962 with China; feud with Sri Lanka over supporting Tamil Tigers, likewise case being with Nepal. However, the argument that India’s relations with its neighbours are only acrimonious appears to be vague.For instance, it shares cordial ties with regional states in terms of trade and economics. Nepal being a landlocked state has relied significantly upon India pertaining to its trade, travel and communication. Similarly, India holds an edge over the bilateral contours of relations with Maldives and Sri Lanka as well. However,with the advent of Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, concerns from New Delhi started echoing. The peaceful rise narrative indicated the non-interventionist intentions of China vis-a- vis its relations with BRI member states.

China was not a member of the United Nations after its establishment in 1945 due to various political and ideological reasons. It was not until 1971 that it became a member state as well as a member of the United Nations Security Council, holding Veto power. This gave China reasonable power at the multilateral level. With the gradual economic and political reforms in China, a remarkable metamorphosis occurred with an increased assertiveness and activism within international organizations. Furthermore, it holds this position whereby it stands as representative of the third world states.

After repeated applications for membership, China was accepted in the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. To revamp its global economic status, it needed an external factor to compensate for internal discrepancies, which it eventually gained through WTO membership. In doing so, China cut down its tariffs, unified exchange rates and as a result, FDI and exports soared. Moreover, the US granted China the MFN status after it became part of the WTO. India remains increasingly sceptical of China’s economic dominance and it even raised its concerns at the WTO forum pointing out the Sino-Indian trade deficit, restrictions for its qualified personnel into China and several export obstacles relating to the IT sector. The trade deficit of both states accounted for $60.1 billion in favour of China in 2018.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has repeatedly been seen using this approach; he even invited the South Asian Regional Association Cooperation (SAARC) members to his inaugural ceremony. Multilateralism has become a lynchpin of his policies starting with the annual UNGA meetings in New York, to attending the G20 summit in Australia, East Asia summit in Myanmar and the East Asia Summit in Nepal. All these multilateral avenues present an opportunity for India to advance its political and development agenda. There is a dominant narrative amongst Indian policy makers that China’s quest for global influence is intended to contain India through undermining its role on regional platforms. This encourages New Delhi to compete. India, for instance, gained the status of a vital maritime state as Exclusive Economic Zone under the treaty of the law of the sea despite its lack of maritime capabilities and continues to do so, particularly under the second term of Prime Minister Modi.

India does not accept China’s maritime diplomacy as part of a stable rise in the IOR and thus, raises concerns regarding its implications on India. According to an article, China’s implications for India are three-pronged: as a maritime, economic and as a polygonal power. India is faced with the pressure of a rising naval power in its own backyard, which will lead to a concerted competition in the maritime domain. New Delhi has to devise policy blueprints to maintain its regional dominance in South Asia by maintaining its trade ties with its neighboring states.

Bringing the United States into the mix, both India and the US have a convergence of interest in terms of containing the rise of China in Asia, which allows them to cooperate along a dynamic policy formation vis-à-vis China which ranges from cooperation to competition and conflict.

The strategic importance of the Indian Ocean is quite apparent. The main argument relies upon the fact that China’s economic initiatives and measures are translated as security concerns for India. Thus, it remains to be seen objectively, whether economic power can be isolated from national policy objectives and hence hold capability. The deployment of naval hospital ships by the People’s Liberation Army of China, the Navy remains a point worth considering. These hospital ships were established in 2007 and patrolled across the world, including the South Asian region; this turned many heads in the US and in Indian policy making elites.

Recently, China has enhanced its representation at multilateral security forums and has successfully become an ‘observer’ in Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Indian Ocean Nava Symposium (IONS). Moreover, the development of Chinese ports under BRI provide impetus for China to have high stakes in the IOR. Increasing Chinese capability in the IOR is likely to affect the regional balance of power, if not change it in favour of China with respect to US predominance in IOR. India also plays a key role as it aspires to dominate the IOR considering the significance it holds. However, China perceives the US to be its major competitor, not India. Hence, India’s policy framework remains expansive and there is room for meeting strategic goals via furthering geo-political convergences with Beijing and seek economic advances from being part of the broader trade and infrastructure development program of the MSR. However, it is yet to be seen how the policies of India are framed and what narrative they seek to establish relations with China over key geo-strategic and economic issues.

In the midst of “Great Game politics” and daunting regional security challenges, India’s strategic culture is predominantly framed around containment of Beijing’s economic projection and balancing military prowess in South Asia. However, its economic power foray was preluded with skepticism due to its reliance on strategic assertion and coercive policy measures over territorial disputes with nuclear regional states-Pakistan and China.

Whilst focusing on rapprochement and reconciliation, through establishing multi-dimensional ties with SAARC – extended primacy over weaker regional states, Delhi vows to expedite cordial ties with the US, Japan and Russia in order to further its regional relevance in geopolitical and geostrategic affairs. Thus, Indian converging and diverging interests revamped the dynamics of competition and contention among the powerful actors in South Asia while the weaker states foreign policy remained a mirror image of their alliance assimilation.

Some of India’s perspectives are mentioned below:

• India proclaims that China refutes universally attested lending practices while predominantly securing its interests through debt diplomacy and lack of transparency and accountability in Beijing’s lending disguises its risk to recipient states.

• Through BRI, China is setting up another East India Company by projecting economic and political colonization providing small benefits to the actors, whereas actually building a political empire through strengthening itself at negotiation tables.

• BRI principle of regional connectivity encapsulates conditionality for joining actors which would impair sovereign decision-making abilities of countries for self-efficiency and independent sustainable growth.

• China’s investment in South Asia, South East Asia and Central Asia would not yield profitable outcomes as per estimations, thus promoting sense of insecurity among states involved in mega projects in collaboration with Beijing.

• In the context of CPEC, the flagship project of BRI holds numerous apprehensions as India perceives it as a threat to its national security and territorial integrity.

• BRI lacks obligations pertaining to standards of preservation, balanced environmental and ecological protection and feasibility cost of projects.

The hallmark of India’s counter-responsive measures vis-à-vis China’s economic expansionist clout in South Asia revolve around China’s pouring in heavy investments for propagation, exploitation, indoctrination and benefiting through vulnerabilities.

In the context of China, the void of western values and democracy, the notion of economic power not only exists but also thrives. Economic interdependence in today’s globalized and fast paced world is essential, especially for the weaker and less developed states of South Asia.

There is a conflicting relationship between India and China. The economic initiatives of the later have increased the strategic vulnerabilities of the former. India does not have enough economic power to compete with China and thus, unilaterally cannot provide regional infrastructure programs that match the likes of China.