Surrounded on three sides by the sea and closed in the north by high mountain ranges, the relatively segregated geographical position of the subcontinent and the strong and persistent influence of the Indian caste system have resulted in certain specifics with regard to Indian Islam. One is that the spread of Islam has been extremely slow. Even after seven hundred years of Muslim rule the first census reports show an overall Muslim population of no more than 20% though with regional differences. There were two main sources for the spread of Islam: Immigration from central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran and Arabia and conversion of the indigenous population. The immigrants came to be the upper class of Muslims, they consisted only of a small minority. The majority of Indian Muslims are converts from Hinduism or Buddhism. Sometimes, entire castes would convert to Islam at a time. This would happen for many different reasons. Often, however, the hope that equality in Islam would provide an escape from the caste system was a reason. In the caste system, who you are born to determines your position in society. There was no opportunity for social mobility or to achieve greater than what your parents achieved. By converting to Islam, people had the opportunity to move up in society, and no longer were subservient to the Brahman caste. Buddhism, which was once very popular in the subcontinent, slowly died out after the 8th century. It shared the idea of equality of men with Islam, so former areas of Buddhism became preferred places of conversion to Islam.

Such deliberation also shows that mostly people of lower castes converted. Over the centuries it became clear that because of this Islam in the subcontinent inherited many of the cultural characteristics of Hinduism such as the caste system so that the hoped-for upward social mobility of new converts did not happen. In addition, many of the cultural traits of Hinduism such as worship of saints, superstitions of all kinds, caste system and racial preference of white skin colour seeped into Indian Islam so much so that what we call “popular Islam” has many traits of Hinduism. It was Ahmed Raza Khan Barelvi (1856-1921) an Islamic scholar, jurist, theologian, ascetic, Sufi, and reformer in British India who justified the customary Indian Islam, associated with obtaining intercession to God from saints against attempts to purify Islam from those additions. The Barelvi section named after him provides for the majority of Muslims in the subcontinent today. Barelvis are known to highlight even more highly the status of the Prophet of Islam emphasising the Sufi belief pertaining to “Muhammad’s light” against the clear instruction of the Quran that the Prophet was a human being. By approving shrine worship Barelvis cater to the needs of the illiterate rural (and urban) population.

The Barelvi reaction to save “popular Islam” was ushered in the 19th century. by the Deobandi movement. The loss of political power by the formerly ruling Muslim elite under British colonialism the ulama invested their efforts into maintaining Muslim society under the onslaught of British education, laws, Christian propaganda. A movement called “revivalist” tried to go back to the original teachings of Islam. The most significant efforts were spearheaded by those ulama who followed Shah Wali Allah and were inspired by Sayyid Ahmad Barelwi’s jihad.

Shah Waliullah Dehlavi was the most important reformer of 18th century. India. Seeking to give theological and metaphysical issues a new rational interpretation and labouring to harmonize reason and revelation, he tried to reconcile the various factions of the Indian Muslims, thereby trying to return to original Islam. Shah Waliullah contended that the root cause of the downfall of the Indian Muslims was their ignorance of the sacred scripture of Islam. He initiated a movement with the theme ‘Back to the Qur’an’, and translated the Qur’an into Persian to facilitate its understanding among all the Muslims of India. His is the first complete translation of the Qur’an from the Arabic by an Indian Muslim scholar, a revolutionary step to make the Quran available to all (literate) Muslims.

Syed Ahmad Barelvi’s reformist teachings were set down in two works that, when printed on the new lithographic press of the day, soon achieved wide circulation. The Sirat’ul Mustaqim (the Straight Path) was compiled in 1819. Written initially in Persian, it was translated into Urdu to reach a wider audience. The second work, Taqwiyatul-Iman or the strengthening of the faith, was written directly in Urdu. The two works stressed above all the centrality of tawhid, the transcendent unity of God, and denounced all those practices and beliefs that were held in any way to compromise that most fundamental of Islamic tenets. God alone was held to be omniscient and omnipotent. He alone is entitled to worship and homage. The next step was taken by Muhammad Qasim Nanawtwi and Rashıd Ahmad Gangohi in 1867 founded a madrassah in Deoband in UP where they started teaching their views. They shunned all British, Hindu and Shia influences and only permitted some Sufi practices while completely proscribing the concept of intercession at the shrines. In the footsteps of Shah Waliullah, they stressed reliance on the Quran. According to them knowledge of divine law and expected Muslim behaviour was a prerequisite for preserving the Muslim community in modern times.

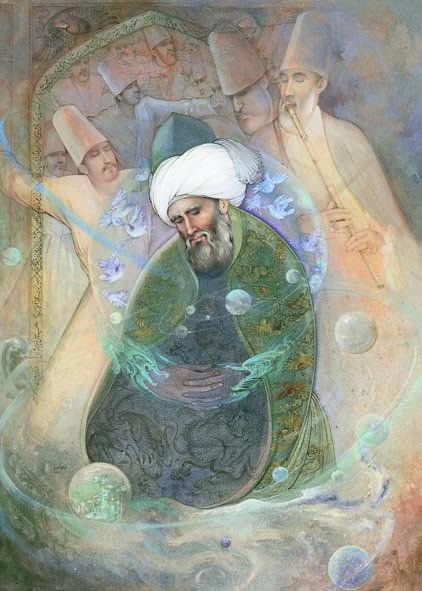

The Ahl i Hadith shared the Deobandis’ reformist and revivalist roots but believed that they did not do enough. AH religious ideas were more radical, more sectarian and they came from a more elite class. They shared the Deobandis’ commitment to cleansing Muslim culture of acts not in compliance with the Sharia. But while the Deobandis espoused taqlid and embraced the Islamic scholarship they had inherited, the Ahl i Hadith repudiated it and directly used the textual sources of the Quran and Sunnah and advocated deploying the methodologies used by the original jurists of the Islamic schools of thought. This methodology meant that the followers would have a heavy individual duty. To enforce this duty the Ahl i Hadith completely spurned Sufism. Sufism has a long history in South Asia. It is a method to highlight the mystical side of Islamic belief and practice in which Muslims seek to find the truth of divine love and knowledge of God through direct personal experience of God. Various leaders of Sufi orders, tariqa, chartered the first organized activities to introduce localities to Islam through Sufism. Though the main tariqas originated outside South Asia, Sufis came to the subcontinent and opened their branches here. Four main tariqas are present in South Asia (Qadiriyya, Chistiyya, Suhrawardiyya, Naqshbandiyya) but Sufism raised also critique, for example that of Allama Iqbal. Despite the fact that Iqbal was a Sufi and believed in the supremacy of Ishq over Intellect, the soul over the body, he was critical about the way modern Sufism was practiced. In his lecture on the “Spirit of Muslim Culture” he related the following story of a great Muslim saint, ‘Abd al-Quddūs of Gangoh who is quoted as having said: “Muhammad of Arabia ascended the highest Heaven and returned. I swear by God that if I had reached that point, I should never have returned.” Iqbal critically remarks that the mystic does not wish to return from the repose of this “unitary experience”; and even when he does return, as he must, his return does not mean much for mankind at large. The prophet’s return, on the other side, is creative, he returns and uses His insight to change the world and human society.

Contributed by:

Dr. Bettina Robotka, former Professor of South Asian Studies, Humboldt University, Berlin, Editor of the Defence Journal and a Consultant to the Pathfinder Group.