When looking at the map there are mainly three North-South connecting routes that would come to mind. The first is the route coming from China/Tibet through Nepal and India reaching down to the western ports of Bangladesh at the Bay of Bengal, Mongla or the forthcoming port of Payra. Parts of this connection are already in place, some other parts are still missing. In 2016 China announced the construction of a China-Nepal friendship road, a road and rail connection to Nepal with the purpose of promoting trade. It starts from China’s western Gansu province and reaches Kathmandu through Xigaze in Tibet, the last point on the Tibet railway network in the west, with the goods then transferred to road transport until Kathmandu. By 2018 more than 10 agreements involving technology, transportation, infrastructure and political cooperation had been signed between the two countries. The Nepalese PM Oli disclosed to reporters that “cross-border connectivity” was Nepal’s top priority. From the very beginning China has had a “Himalayan Economic Corridor” in mind that would include India and Bangladesh, but India so far has been a rather reluctant partner. Since then, China has been very active in developing infrastructure through Tibet, right through to the border with India, where smart new multi-lane highways come up to an Indian border all-together devoid of infrastructure. China has been keen to develop outlying towns of the Tibet Autonomous Region, and has done so with the Beijing-Lhasa railway being extended to Shigatse in 2014, Tibet’s second largest city. The Nepali government has also asked China to expand the Arniko Highway as a four lane highway connecting Tatopani, near Shitagse to Kathmandu.

This is causing concern for Indians on their side of the border, watching Chinese funded infrastructure and wealth being generated on the Tibetan side. The same is partially true in Nepal, and creates both consternation and embarrassment in Delhi.

Kathmandu, on the other hand, has been enthusiastic about receiving larger amounts of Chinese investment. Nepal is reliant on India for the movement of its goods, is keen to reduce that dependence and wishes to present itself instead as a transit hub for cross-Himalayan trade. That would link it with China’s Yunnan, Sichuan and Gansu Provinces as well as with Tibet and allow it to process trade between China and India.

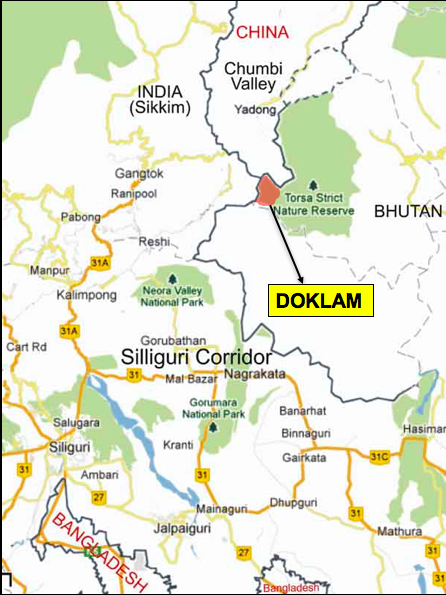

A second connecting route would be from China through Bhutan, India down to Kolkata, Mongla or Payra. But there are serious problems for the time being that prevent a fast progress of this connection. Bhutan’s border with Tibet/China has never been officially recognised and demarcated what created trouble. Chinese govts thought of Bhutan as belonging to China for quite a while. In 1998, China and Bhutan signed a bilateral agreement for maintaining peace on the border thus recognizing Bhutan’s sovereignty. But the border area was never properly demarcated. When China began stepping up its infrastructure program BRI announced in 2013 road construction started in Tibet close to the Bhutan border in the area of the Doklam plateau which China considers part of Tibet. This led to a border crisis in 2017. Bhutan protested to China against the construction of a road in the disputed territory of Doklam, at the meeting point of Bhutan, India and China. The Indian army blocked the Chinese construction of a road in what Bhutan and India considered Bhutanese territory in a 72-day stand-off. Since then, China has been stepping up pressure on Bhutan to settle their bilateral border dispute so as to be able to proceed with the infrastructure development. Bhutan has ever since Doklam been dismissive of China’s intrusion into the country, whether in economic or political terms. China has intensively tried to build official bilateral relations and partner with Bhutan on the BRI, but Bhutan has continuously declined despite the pressure. So this connecting channel needs more time to become viable.

The third corridor would be from China through the ‘Seven Sisters’ (that have become eight actually after the addition of Sikkim in 2002) to the eastern ports of BD Chittagong and Matarbari. Here there would be two main constraints: one, the political tension between China and India and India’s membership in anti-China alliance Quad. And secondly, India’s northeast is and has been in turmoil for decades. Even when lately separatist movements have lost some steam, most of the insurgent groups exist mainly to make money through extortion, kidnappings, tax collection from local people, demands for toll from development projects and attacks on communication links and energy infrastructure. Furthermore, northeast India is an important transit route for heroin trafficking from the neighbouring “golden triangle” of Myanmar, Thailand and Laos to Europe, with local insurgent groups involved in this flourishing trade. Thus, the building of an economic corridor will be risky through this region at least during the foreseeable future.

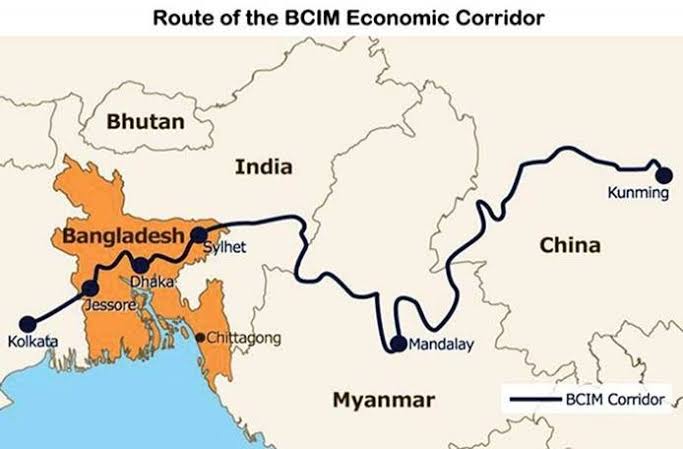

There is a fourth project already under partly construction on the Chinese side: The Bangladesh China India Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM-EC). The Bangladesh China India Myanmar (BCIM) Forum for Regional Cooperation, earlier known as the “Kunming Initiative” is part of China’s BRI program. The BCIM-EC is planned to extend on three routes: one, known as K2K, will run from Kunming to Kolkata via Myanmar, Northeast India and Bangladesh; the other two will go from Mandalay of Myanmar to Chittagong of Bangladesh in one direction, and to Sittwe seaport at Rakhine state of Myanmar in another direction.

The large trans-border region, connecting Bengal in India, Bangladesh, Burma/Myanmar, and Yunnan in China to each other, has been shaped by multiple polities under the pressure of global empires. In this project we strive to understand the complex and interlinked webs of relations within the region during the formation of modern Asia. Two related aspects are given special importance: the role of natural conditions and the impact of human mobility in the historical processes shaping human and human-nature relations. There remains ethnic insurgency in Northeast India and Myanmar as well as the Rohingya issue between Bangladesh and Myanmar, which poses lasting security threats to the building of the Corridor. Even when the corridor is completed, transportation of personnel and goods may still face constant security threats from local insurgency. The same is true for the Rohingya insurgency in Myanmar.

In addition, India has never participated full-heartedly in the BCIM EC negotiations. The Kathmandu Post in an 2020 article called it a “camouflaged participation” China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has shaken up India’s hegemonic balance and given other, smaller regional nations a chance to rise up against the dominant influence in the region. China has been penetrating regional diplomacy in South Asia, all the while keeping in mind its larger aim of further securing its Westers territory. For countries in the region such as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, the BRI is seen as a more neutral, if not benign force and has pushed India to become more considerate of changes. But small countries like Bhutan that are ethnically and culturally so close to Tibet/China fear to be overwhelmed by the large neighbour though the Indian alternative is threatening as well.

New Delhi feels uncomfortable with all Chinese attempts to secure road connection via the Himalayas and port access agreements along the Indian Ocean in places like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, and New Delhi is probably watching Myanmar closely as well. The bottom line is that India will not want to relinquish its dominant position in the Indian Ocean and it will take time to make it do so.

While China has aggressively sought to connect its borders, India neglected its own, creating massive disconnects between its borders and hinterlands, especially on its Himalayan front. By helping create multiple access points via roads and ports, China is able to present an alternative to South Asian nations and cultivate the means to challenge India’s role as a South Asian power.

Contributed by:

former Professor of South Asian Studies, Humboldt University, Berlin, Editor of the Defence Journal and a Consultant to Pathfinder Group).

Dear Sir,

A very “perspective” article indeed. This would become a reality if China gives up its ‘expansionist’ Policy towards its Southern neighbours, which is very intimidating indeed. It has already taken Tibet. Why should it then raise its glance beyond the Himalayan crest-line, then? When there was British India in power, China never had the guts to even step into Tibet, which enjoyed its neutrality and serene existence. The British Foreign Policy in Asia has been a colossal failure in the long run, because it did not realise the importance of balancing an “emergent China” in the future. They were focussed on retaining influence in the oil producing West Asia region at all costs. We will have to wait for change of leadership in China before such productive arrangements can get undertaken, because this needs taking all Nations involved on board without even a scant threat of military muscle-flexing being a reality, even in the shadows!

Thank you Sir/Madam on bringing to everybody’s notice the future possibilities, which has been lying dormant since the commissioning of the famous ‘Ledo Road’ in end 1944.