No point in forcing them to live under shadows, they stood for Pakistan and are loyal to the core

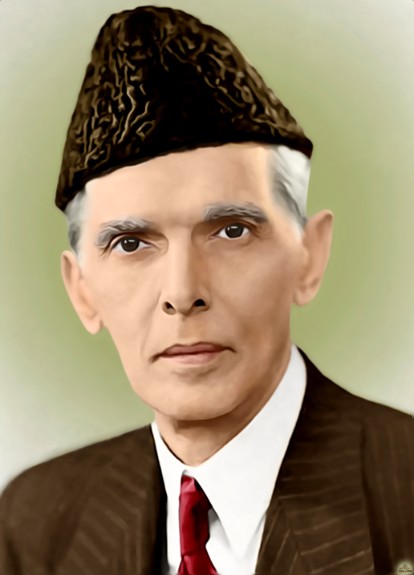

MUHAMMAD ALI JINNAH, the Founder of Pakistan, had once quipped that ‘Muslims (of the subcontinent) who are opposing Pakistan will spend rest of their lives proving loyalty to India.’ Prophetic words, indeed. But there is an antithesis of sorts in Pakistan, too. More than three million Bengali Muslims, who were part and parcel of Pakistan before the 1971 truncation tragedy, are not only longing for their new identity but run from pillar to post to prove their loyalty to the State of Pakistan!

The trajectory of history is that these people never accepted Bangladesh as their country, didn’t become part of the uprising against Pakistan and its armed forces in the then Eastern flank, and were completely loyal to Pakistan. This loyalty syndrome has cost them their identity. This second generation of Bengali Muslims is living in Pakistan as ‘third class citizens’; and haven’t been accepted as “natives”. They speak Bangla and Urdu both. They have never returned to their root, Bengal, but have relatives in Bangladesh.

Before we go on to dissect the issue and dwell into its socio-political ramifications, it is necessary to make a distinction. The uprooted, identity-scared Bengali Muslims in Pakistan are not Bangladeshi. Similarly, there are other chunks of illegal immigrants in Pakistan such as Burmese, Afghanis, Iranians and even Indian Muslims who choose to make Pakistan their ‘new home’ for reasons of exigency or economic appetite. The faux pas that the Bengalis chose in terms of their political inclination is squarely responsible for their plight today.

It is ironic that the two epicenters of Pakistan Movement today are on the other sides of the divide. They are Uttar Pradesh in India, and Bengal in Bangladesh. Something went seriously wrong, and the cherished slogan of ‘Muslims as one nation’ saw them sophisticatedly get divided into three separate states.

There are around three million Bengalis in Pakistan, and their status is that of aliens. Most of them dwell in Karachi. In other words, 10 percent of Karachi’s population comprises ‘illegal’ Bengalis. Other sizable chunks are in Golarchi, Badin, Lahore and Rawalpindi. Some are dislocated around in the restive belts of Balochistan and FATA, too.

They are the poorest segment of the society. But they are an industrious and passionate workforce. Their trade is mostly fishing, household services, labour and small-scale merchandise. Less than five percent are educated to hold white-collar jobs. They are societal prime suspects for theft, murder and car-jacking; and are inadvertently blamed for prostitution, too. Most of them are born in Pakistan to Bengali parents after 1971, though. Very few have been able to get hold of official documentation as Pakistani citizens, and the rest long for it till to-date.

Being one of the world’s largest refugee-hosting nations, Pakistan received around a million Bengalis during the 1971 unrest in East Pakistan. And when the Eastern flank broke away and became Bangladesh, their identity and citizenship became an enigma overnight!

Moreover, there are around half-a-million Burmese living in Karachi. They had lived in Pakistan for decades and that too in shadows. The post-1971 trauma created a perfect linkage between Burmese and Bengalis, and their free-mix created a new security alert which hangs on to this day.

Let’s look at the legal tangle in this crisscross. The complexity is that being a resident Bengali [in Pakistan] is not a crime, but a Bangladeshi [illegally residing in the country] is against the law. This is where the lingual Bengalis get mixed up.

The Pakistan Citizenship Act 1951 states that “every person born in Pakistan after the commencement of this Act shall be a citizen of Pakistan by birth”. The same law stipulates that people who were residing in territories that comprise Pakistan prior to Dec 16, 1971, would continue to be citizens of Pakistan, and their children would be considered citizens of Pakistan by virtue of their descent.

The onus as per law is on the Bengalis to prove that: either they were born in Pakistan [East or West before Dec 1971]; or parents were living in what was then West Pakistan; produce father’s employment record or documents that demonstrate the family’s circumstantial linkage with the territory of Pakistan. Other bona fide credentials are: attested documents showing the purchase or ownership of a piece of land, a domicile certificate; attested revenue department deeds; educational certificates; passport or identity card; arms license; or any other document issued by the competent authority.

Then there is a loop in the law termed by many as lacunae of sorts. The Interior Ministry guidelines on the process of verifying and revoking National Identity states that ‘a person would be accepted as a Pakistani citizen if he/she can prove that the incumbent has been residing in Pakistan prior to 1978 providing an approximately seven-year extension to the date set in the citizenship act. This is where the generational crisis begins.

Most of the Bengalis in Pakistan claim that they were uprooted after 1971 in the then East Pakistan and came over to the Western flank, and the rest were permanent residents of West Pakistan, and were apolitical in the crisis. But the Sword of Damocles to prove their ‘identity’ and ‘loyalty’ hangs on both the segments. Of course, there is a margin of five percent people who may be Bangladeshis and moved over to Pakistan, as well as ethnic Indians.

Thus, Bengalis were forced to adopt various means to ascertain Pakistan identity documents, legal or illegal. In the 1970’s as National Identity Cards were made manually, many overcame the odds. The lucky ones got those cards converted into computerised identity cards (CNICs) in the early 2000s. Hundreds-and-thousands, however, failed the litmus test as officers resorted to arm-twisting; and lingual-ethnic riddles were tossed over them.

The government then came up with a novel idea to issue Alien Registration Cards and this is where the nationalism sentiments got ignited. Pakistani-Bengalis rightly questioned as to why they should live under the umbrella of ‘otherness’ when they are equal ‘sons of the soil’, and patriotic, too. The State’s intention was to differentiate between legitimate Pakistani Bengalis from illegal migrants from Bangladesh. The effort torpedoed.

Pakistan, at times, tried to deport thousands of people to Bangladesh, especially in 1995-96, but Bangladesh refused to take them back.

Former Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan is on record having said that his ministry has blocked or cancelled around 400,000 CNICs issued to alleged migrants of dubious characteristics, especially Bengalis.

This witch-hunting campaign against Bengal-origin people is prejudiced, to say the least. Millions of Afghan refugees for reasons best known to the State of Pakistan were not treated with the same sense of vengeance. They freely moved across the length and breadth of Pakistan, conducted businesses of all kinds, and managed to obtain Pakistani identity documents by hook or crook. The writ of law was superstitiously silent for them.

Most of the Bengalis neither possess any government-issued identity document, nor the aliens’ card. They are often on the receiving end at the hands of police and security agencies. Three Censuses were held since the 1990s, and Bengalis were not counted as citizens.

The political equilibrium of the inferior community is chaotic and polarised. Both the MQM and Jamaat-e-Islami support granting citizenship to people inside Pakistan of either origin: Bengali and Rohingya-Burmese but they have not been able to do anything on the legislative front other than lip-service. Whereas, the major stakeholder in Sindh, the Peoples’ Party and other nationalist parties are daggers drawn against the marginalised community.

It was music to the ears as Prime Minister Imran Khan on September 17, 2018, vowed to grant citizenship to Bengali immigrants. He was addressing his debut public rally in Karachi after assuming his office. The premier said, “The first thing I will do going back (to Islamabad), God willing, is that we will get those people from Bangladesh, who are perhaps living here for more than 40 years and their children have grown older, issued passports and national identity cards.” A generous and humane proposition, indeed!

The illustrious Prime Minister noted that Bengali immigrants and Afghan refugees have created an “underclass” in Karachi that has helped fuel street crime in the megacity of more than 20 million people. He went on to say: “When you are born in America, you get the American passport. It is the practice in every country in the world, so why not here? How cruel it is for them (Bengalis and Afghans).”

Mr Prime Minister, you are right. Walk the Talk.

It is quite unfortunate, nonetheless, that no headway has been made since then. No summary moved in the Interior Ministry nor any legislative agenda planned to streamline more than three million disgruntled souls into the national artery. Like innumerable standing committees that previously promised to look into this issue, this initiative too seems to have ended up in doldrums.

It’s time for Pakistan to address this issue with a prudent mindset. This will swing in a momentum of goodwill both at home and on the diplomatic front. Pakistan’s relations with Bangladesh have been at their lowest ebb, and conformity is missing on almost all counts. Perhaps the 1971 trauma has to do a lot with this; but it is also a reality that Islamabad didn’t walk the few extra miles to woo the Bengali brethren since the dismemberment of East Pakistan.

Prime Minister Imran Khan should foresee a diplomatic metamorphosis in his initiative of legalising illegal Bengali immigrants at home. It will strike the right chord with Bangladesh, too. Of late, Islamabad has taken a leap forward in mending fences with Dhaka. The telephonic conversation between Prime Minister Imran Khan and his counterpart Sheikh Hasina Wajid in July 2020 has already set the ball rolling. After a long hassle, Pakistan High Commissioner to Dhaka, Imran Ahmed Siddiqui’s credentials were accepted; and Pakistan’s Foreign Office spokesperson Aisha Farooqui elucidated, “we are working on moving forward” with Dhaka.

Mr Prime Minister, please understand the Bengalis’ wretchedness. Unlike Afghans, Indians, Iranians and Burmese, these destitute do not have a home to go back to. They cannot be repatriated. Bangladesh repels them and suspects their troth. Moreover, why should they go? They are part of Pakistan’s dispensation and have braved through thick and thin. Discriminating them for generations for a bad phase of our common history is unwise. Legalize them, and usher in a new era of nationalism. It will be politically-correct.