Introduction

Cyberspace had been an important discourse within the ambit of international information security mostly examined through the lens of non-kineticism, where state actors along with non-state actors are blamed to exploit the unchecked world of internet. The impetus in the information technology and global reliance on communication through internet had opened a new theatre of competition that with the induction of state sponsored operators changed it into a ‘digital battlefield. From hacking to financial frauds, the mode of silent infiltration has manifolded its intervention into government organizations. The discourse and the dilemma of cyberspace is not only considered a challenge that public domain faces at global level, it is in fact an emerging dilemma of national security that powerful states have opted to ignite in relations to challenge each other’s dominance. For example, the cyber attacks on Iranian nuclear facility in 2010 conducted through a computer worm malware coded as ‘Stuxnet’ with that of July 2, 2020 attack on the same facility that killed around 18 people are the glaring examples of exploiting the cyberspace. Contrary to this, Washington’s claims over Chinese theft of intellectual property rights with that of Russian meddling of her Presidential elections had already contextualized the dilemma of United States national security. Cyberspace therefore has been upgraded to a whole new level of national security, just like a nuclear threat during the Cold War.

The Cold War mantra of national security between the two superpowers, the United States and the former Soviet Union, was no doubt based on the possibility of nuclear attack, where no third party created the discourse or the dilemma being the bidder of insecurity. That is why it was a bilateral competition camouflaged with direct-indirect mode of confrontation. But today, the threat spectrum around cyberspace has involved actors, factors, and associated characters in such a way that has included not only state actors as tangible operators but all non-state actors that are integrated with the philosophy of global chaos. This makes the puzzle more problematic because identifying the real culprit or the operator behind any cyber attack is almost impossible. The only thing which is identifiable is the incident itself; the rest is just a blame-game. With a view to underscore the challenges that cyberspace can cause to any state, a paradigm shift in coding the discourse of national security has been deemed necessary in the 21st century.

What Goes Around Comes Around

It is difficult to identify who has been the biggest victim or the leading player with utmost success in the domain of cyberspace. What makes the debate more directional and helps to peel the surface of the problem is the so-called technological capability that only few states possess. This hypothesis without any doubt highlights the United States as the only dominant player in the domain of cyberspace. The supremacy in the field of information and communication technology altogether does not deny the fact that the United States is facing enormous challenges to its national security out of cyberspace. In fact, the U.S. claims about Chinese infiltration with that of Russian penetration are the true sources of threat spectrum in cyberspace. Also, the so-called Iranian and the North Korean intensions with that of their continuous efforts to undermine U.S. public and governmental infrastructure altogether reflect the true manifestation of challenging Washington’s global writ.

The matter is not under contestation that the U.S. is not facing these threats. Yes, it is facing. But the question that needs to be answered is, why the U.S. is facing challenges in the cyberspace? In fact, the shortest answer is that it had already exhausted the domain of cyberspace against its opponents. Now, after achieving certain level of efficiency and capability, the so-called rivals have started exploiting the dormant space of cyberspace that was earlier only used by the United States. It is simply a response by those who initially faced it without any repulsion. Seeking help from the Newton’s 3rd Law of Motion, this situation can be easily explained as “for every action (force) in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction”. From the Cold War bipolar threat spectrum to 21st century multipolar threat spectrum, the narration of contestation in cyberspace is very simple, “what goes around comes around”.

From Eisenhower’s ‘Solarium Project’ to Trump’s ‘Solarium Commission’

Before, this part of the paper shed light on the U.S. Cyberspace Solarium Commission that was established in May 2019 and purpose behind it, the author wants to add another point into the ongoing discussion. The point is related to the course of history which identifies a pattern of U.S. national security thinking with that of legislative response. Of course, the United States of America is a functional democracy; therefore the responses it generates against any threat have to qualify institutional debate such as endorsement by the Congress. When it comes to exercise its military power, the U.S. leaders simply change the normality of democratic endorsement into abnormality of the national security priorities. For example, the U.S. leaders without seeking the democratic endorsement would drop nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945 respectively. After all, in so-called national security calculations, it was deemed necessary to kill more than 200,000 innocent civilians. The U.S. had not only enjoyed its superiority but exercised it without being accountable. But when they got a competitor in the nuclear field such as the Soviet Union that detonated its nuclear device in 1949, the U.S. considered it the top most national security threat. And see what, the then U.S. President Eisenhower under the National Defense Authorization Act made the ‘Solarium Project’ in 1953 to develop a comprehensive plan of action with that of legal instruments to counter Soviet nuclear threat. So, it was the Solarium Project of 1953 that helped Eisenhower to develop the comprehensive approach, one that would inform the subsequent “New Look” policy, along with the NSC 162/2 policy paper, to stabilize the Cold War.

Taking the lead from Eisenhower, in May 2019 through National Defense Authorization Act the U.S. Cyberspace Solarium Commission was chartered to address national security challenges related to cyber attacks. The President and Congress tasked the Commission to answer two fundamental questions:

- What strategic approach will defend the United States against cyber attacks of significant consequences?

- And what policies and legislation are required to implement that strategy?

The Trump’s Solarium Commission of 2019 differs from the Eisenhower’s Solarium Project of 1953 by focusing on three concerns about cyberspace rather than a single nation like the Soviet Union.

- First, the commission aims to determine what role both the public and private sectors should play in securing America’s critical and information infrastructure.

- Second, the commission wants to decide how Department of Defense should address cyber attacks from foreign nations that damage U.S. economic and national security.

- Third, the commission seeks to address how America and its allies should promote and enforce government “norms” in cyberspace.

The first part is to bring back the U.S. leading corporations to play shoulder to shoulder in mitigating the so-called space which is being exploited by the rogue or revisionist states. Well the discourse around ‘rogue states’ or the ‘revisionist states’ is not old. One can find clear distinction of the two words in U.S Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), National Security Strategy (NSS), and even in Missile Defense Review (MDR). Briefly, the word ‘rogue states’ connotes Iran and North Korea, whereas the word ‘revisionist states’ describe China and Russia being the two global challenges to its dominance. The role of public and private sector in securing U.S. critical and information infrastructure will of course come through the required legislations that would altogether change traditional way of doing global business by these corporations. In simple words, starting from devices to the domain of human resource, the rogue and the revisionist states would be under stern scrutiny. The rest is just the Pandora box that if opened would lead to global chaos, particularly for the belief that ‘multinationals are the engine of economic growth’.

The second point is very clear. In fact, it provides the same old power to the Department of Defense to identify ‘axis of evil’ in international relations of United States. The job is already done. The Department of Defense along with State Department through their rigorous efforts has already directed this point in U.S. national security policy papers. Like NPR, NSS, and MDR; the discourse of ‘rogue states’ and ‘revisionist states’ are the so-called foreign nations that damage U.S. economic and national security. The strong direction along with clear conviction has been already done against China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. The Department of Defense just needs to paraphrase and put forward the same old ‘axis of evil’. Don’t we know that they are exceptionally good in that?

The third point is about “no one will be left behind” which is not biblical rather apolitical narration of the so-called “union is strength”. Interestingly, this union is not for global partners rather an alliance of likeminded countries that could be simply contextualized as ‘the westerners’. Nations can jump into this alliance but they have to distinguish their ideas with that of ‘rogue states’ and ‘revisionist states’. For the unwise, the reminder is very simple “you‘re either with us, or against us”. Whatever is the price, at-least no state will be told this time “be prepared to go back to the Stone Age”. The distinction is already done and it has been going on in international forums since many years. For example, China and Russia have already floated their ideas of regulating the international information security that the U.S. regardless of joining has put forward his own distinctive voice. Few important distinctions are mentioned below:

Cyber Sovereignty vs Cyber Freedom

Countries such as China and Russia unequivocally support the principle of cyber sovereignty, while Western countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom vigorously advocate the idea of cyber freedom. Although the US expects to occupy the international moral high ground through cyber diplomacy, many developing countries fear that freedom in cyberspace is just another pretext for the West to meddle in their internal affairs and violate their sovereignty, and worry that the West is seeking to engage in “color revolutions” through cyber means so as to undermine their national security, stability and development. Cyber sovereignty is a natural extension of national sovereignty in cyberspace. After years of continuous negotiations, especially the persistent efforts of the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts (UNGGE) on information security, the principle of cyber sovereignty has been recognized by such international organizations as the United Nations and NATO and countries such as the United States, thus laying the foundation for future global internet governance and cyber strategic stability. However, the meaning of cyber sovereignty is still disputed.

Multi-lateral Approach vs Multi-stakeholder Approach

With regard to internet governance, countries such as China and Russia support the multilateral approach with governments taking a leading role, while the United States and other Western countries advocate a multi-stakeholder approach in which multiple actors participate, thus diluting the role of governments. The latter maintains that internet governance should take a bottom-up approach, in which actors like technical communities, individuals, and internet companies play a leading role, while governments are only one of the stakeholders. In contrast, the multilateral approach is more in line with the national conditions of China, Russia and developing countries whose primary task is to strive for IT development. In this process, there is no doubt that their governments play a greater role in planning, guiding and coordinating the development of cyberspace.

Cyberspace Militarization

For over 20 years, nation-states and non-state actors have used cyberspace to subvert the elements of power, security, and the strategic culture that defines the way of life for a nation. Despite numerous criminal indictments, economic sanctions, and the discussions of robust cyber and non-cyber military capabilities, the attacks against the nations states are continuously happening. The operators consider opportunities that their onslaught damaged the opponents without triggering a significant retaliation. Washington claims that Chinese cyber operators stole hundreds of billions of dollars in intellectual property to accelerate Beijing’s military and economic rise and undermine U.S. military dominance. U.S. also claim that Russian operators and their proxies damaged public trust in the integrity of American elections and democratic institutions. The conclusive conviction of the so-called Solarium Commission report identifies China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea that has probed U.S. critical infrastructure with impunity. Contrary to power matrix in global relations, the criminals leveraged globally connected networks to steal assets from individuals, companies, and governments. Extremist groups used these networks to raise funds and recruit followers, increasing transnational threats and insecurity.

Does ‘Solarium’ Connote Paradigm Shift in U.S. National Security Approach?

The formation of Cyberspace Solarium Commission’s name does find its reference from the former President Dwight Eisenhower’s Project Solarium of 1953. The distinction between the two is that Eisenhower established the project to counter the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and the President later adopted many of its best ideas into his administration’s foreign policy. Much like the original Solarium, 2019’s version envisions sweeping policies with far-reaching historical consequences. The fact is that the Solarium did helped the Eisenhower to change the course of U.S. foreign policy outlook particularly towards nuclear weapons being the ultimate national security threat. With this legacy in mind, one can predict that Solarium does connote paradigm shift in U.S. national security approach particularly towards cyberspace being the ultimate national security threat.

Way Forward for Pakistan and the Information Security

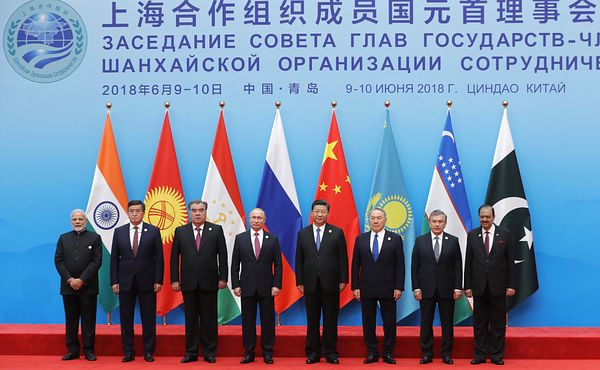

The International Code of Conduct for Information Security (ICCIS) is an international effort to develop norms of behaviour in the digital space, submitted to the UN General Assembly in 2011 and subsequently in revised form in 2015 by member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). According to its sponsors, the Code is intended to push forward the international debate on international norms on information security, and help forge an early consensus on this issue. With its connections to the SCO, the Code raises significant concerns over ambitious but ambiguous posture of international actors especially the Western powers towards their clandestine behavior in the sphere of digital space. The SCO states have been successful in building consensus around the Code given the ‘post-Snowden’ and ‘Arab Spring’ international political environment. Moreover, the SCO states confidently view the Code as a vehicle to redefine notions of sovereignty and territorial integrity to the digital space.

In June 2017, Pakistan joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Being a responsible SCO State means complying with all obligations taken within the framework of the organization. Nonetheless, Pakistan has just started implementing all the relevant agreements, which include almost 30 different protocols.

One of the most important SCO documents is the intergovernmental agreement on cooperation in the field of International Information Security, which is also an effective instrument on combating cyber-crime. As there are two competing models for ensuring IIS: one being imposed by the US and the other is set out in the aforementioned SCO agreement (which Pakistan is supposed to follow since it became full member of SCO).

The White House and its allies have unleashed a kind of an arms race in cyber space, building up its capabilities for affecting the critically important infrastructure of other States with sovereign foreign policy. In August 2017 Donald J. Trump increased powers of national cyber-command on conducting offensive operations abroad. Moreover, decisions adopted at the NATO summit in Warsaw in 2016 clearly show that the Alliance still regards the cyber space as the fourth theater of war, enhancing methods for cyber offense. Release of U.S. Cyberspace Solarium Commission report on March 11, 2020 further indicates Washington’s readiness to cater and classify the cyberspace as next generation battlefield.

It is in Pakistan’s interest to develop a National Information Security Strategy and to design effective means of its implementation. In this regard it is worth using the experience already accumulated by the SCO and increase cooperation in the sphere, which includes providing assistance to the States suffered from cyber attacks.

The SCO platform and its mechanisms are unique. It gives the opportunity to resolve inter-state contradictions through dialogue. The efficiency of the SCO is based on the principle of respecting interests of all members. They try to avoid confronting each other through hasty accusations as the international information security topic is largely sensitive and the source of a cyber attack is extremely difficult to trace. It is vital to focus on shaping a regional International Information Security structure based on the SCO documents. This structure will give Pakistan additional opportunities to protect its sovereignty, cultural and religious values.

The US and its allies continue to enlarge the scale of cyber weapons used to destabilize Muslim countries, first of all by means of the so called ‘color revolutions’, like Arab Spring in Libya. The inter-confessional differences, ethnic and sectarian faultiness, social problems, dependency on foreign technologies and investments are ideal explosives of the cyber weapons. Pakistan is also facing grave challenges of cyber attacks and can also be the target of global terrorist network. In fact, Pakistan has been a target of such attacks with clear intensions to destabilize it. All elements of national power are the targets of cyber weapons that through organized campaigns work to achieve its ultimate goal.

Pakistan’s strategic partnership with China is being considered as an irritant in Washington, because it is a serious impediment for setting US strategic priorities in the region. By now Pakistani national security institutions regard control on cyber-activities as an effective and adequate way to solve the problem but it is not enough as the narrow and simplified vision of Pakistan regarding international informational security does not underscore its strategic vulnerabilities. Due to neutrality and progressive posture of the regionalism vested in Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Pakistan needs to broaden the outlook and start practical cooperation with those SCO Members that have a genuine and substantial experience in international information security China and Russia and can assist in setting out national strategy in this sphere.

The US and its allies refrain from imposing international legal limitations on the development of cyber-weapons. Moreover, the U.S. seeks not only maintaining its leadership but also legalizing cyber space militarization. They continue attempts to persuade other countries including Pakistan to support Western approaches to international information security. These approaches are based on the argument that the existing legal international norms such as ‘the Budapest convention on cyber crimes, 2001’ shall be followed. In fact, this document provides a trans-boundary access to national computer data of the states. It is assumed that the US and its allies exploit this situation to conduct cyber offenses abroad.

At the same time, the status-quo states are trying to distract attention of the international community from the initiatives promoted by SCO and internationalization of Internet. Washington is trying to impose its model of cyber security based on the multilateral approach towards governing the internet, with government playing secondary role. Americans have in fact blocked the work of the UN governmental experts on international information security, which failed to agree upon its final document that included proposals by SCO states. Pakistan could strengthen its authority within SCO through more active promotion of SCO initiatives in different international structures in the field of international information security.

First step in this direction could be joining as a cosponsor to the “International Information Security Rules of Conduct” that have been circulated within UN. Russians also have submitted a proposal on ‘Universal UN Convention on Countering Cybercrime’ that is acceptable alternative to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrimes. It is also important to maintain the UN leading role in all the international information security issues because of economic and social problems many countries face and therefore, do not pay enough attention to the risks of militarization of the cyber space. In this regards, Pakistan could spearhead the formation in the Muslim world that can put a permanent check on the faultiness and future risks like ‘Arab Spring’. The influential group of likeminded Muslim states opposing military conflicts in cyber space and supporting SCO initiatives would definitely be a strategic gain for Pakistan. To start with, organizations like OIC and the OECD can provide launching pad to execute the idea.

After joining SCO, Pakistan should expect more active steps of Western special services inside Pakistani cyber domain to discredit SCO instruments on international information security. Pakistan should show more restraint in bilateral interaction with the US in this field, at the same time engaging deeper in SCO cooperation based on the above-mentioned agreement. One of the potential avenues for collaboration is sharing data on the facts of external cyber-attacks on government-controlled servers and hubs. Such sharing is extremely useful for developing a coordinated SCO response to cyber threats.

References/ Bibliography

According to Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Russian military leaders view the color revolutions as a “new US and European approach to warfare that focuses on creating destabilizing revolutions in other states as a means of serving their security interests at low cost and with minimal casualties. For more details please see, Anthony Cordesman, “Russia and the “Color Revolution”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, (28 May 2014). Available online at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-“color-revolution” (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Council of Europe, “Convention on Cybercrimes,” available online at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/185 (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Ellen Nakashima and Joby Warrick, “Stuxnet was work of U.S. and Israeli experts, officials say,” The Washington Post (June 2, 2012). Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/stuxnet-was-work-of-us-and-israeli-experts-officials-say/2012/06/01/gJQAlnEy6U_story.html?utm_term=.53ba6ae59bfa (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Fred Kaplan, “Russia’s Power Trip,” SLATE (June 14, 2017), available online at: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2017/06/russias-power-grid-cyberweapon-is-scary.html (accessed on June 10, 2020).

For more details please see, “Warsaw Summit Communiqué: Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw 8-9 July 2016,” NATO (July 09, 2016), available online at: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Sen. Angus King and Rep. Mike Gallagher, “Announcing the Cyberspace Solarium Commission,” Lawfare (August 19, 2019), available online at: https://www.lawfareblog.com/announcing-cyberspace-solarium-commission (accessed on June 01, 2020).

See for more details, “Russia Presents Draft UN Convention on Fighting Cyber Crimes in Vienna,” Sputnik (May 25, 2017), available online at: https://sputniknews.com/science/201705251053959333-russia-un-convention-cybercrimes/ (accessed on December 15, 2019). Also see, “Statement by H.E. Mr. Sergey V. LAVROV, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, at the 72nd session of the UN General Assembly,” (September 21, 2017), available online at: https://gadebate.un.org/sites/default/files/gastatements/72/ru_en.pdf (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Michael N. Schmitt, ed., Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Warfare (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 65.

Harold HongjuKoh, “International Law in Cyberspace,” US State Department (September 18, 2012), available online at: http://www.state.gov/s/l/releases/remarks/197924.htm (accessed on June 15, 2020).

See for more details, “International Strategy of Cooperation on Cyberspace,” Xinhua (March 1, 2017), available online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2017-03/01/c_136094371.htm (accessed on June 15, 2020)

Roger C. Molander, et al., Strategic Information Warfare: A New Face of War (RAND, 1996).

John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, “Cyberwar is Coming!” in John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, eds., In Athena’s Camp: Preparing for Conflicts in the Information Age, RAND, 1997, pp.23-54.

See for more details, “Warsaw Summit Communiqué,” Press Release (2016) 100, July 9, 2016, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm?selectedLocale=en (accessed on June 11, 2020)

The White House, “Statement by President Donald J. Trump on the Elevation of Cyber Command,” August 18, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/08/18/statement-donald-j-trump-elevation-cyber-command (accessed on June 22, 2020)

Munish Sharma, “US Ups the Ante in Cyberspace,” August 26, 2017, http://www.eurasiareview.com/26082017-us-ups-the-ante-in-cyberspace-analysis (accessed on June 22, 2020)

See for more details, “Initial operating capability” means that all Cyber Mission Force units have reached a threshold level of initial operating capacity and can execute their fundamental mission. See Department of Defense, “All Cyber Mission Force Teams Achieve Initial Operating Capability,” October 24, 2016, https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/984663/all-cyber-mission-force-teams-achieve-initial-operating-capability (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Nicole Lindsey, “US Cyber Command Signals More Aggressive Approach Involving Persistent Engagement Ahead of 2020 Election,” CPO Magazine (September 16, 2019), available online at: https://www.cpomagazine.com/cyber-security/us-cyber-command-signals-more-aggressive-approach-involving-persistent-engagement-ahead-of-2020-election/ (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Ellen Nakashima, “List of Cyber-Weapons Developed by Pentagon to Streamline Computer Warfare,” The Washington Post (May 31, 2011), available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/list-of-cyber-weapons-developed-by-pentagon-to-streamline-computer-warfare/2011/05/31/AGSublFH_story.html?utm_term=.7fb8069678ec (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Christy Cooney, “US will unleash $2Trillion of ‘beautiful’ military arsenal on Iran if it hits US bases, Trump warns,” The Sun (January 05, 2020), available online at: https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/10673694/donald-trump-trillion-dollars-military-iran-us/ (accessed on June 10, 2020).

See for more details, “It is a historic day’: Pakistan becomes full member of SCO at Astana summit,” Dawn (June 09, 2017), available online at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1338471 (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Sarah McKune, “An Analysis of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security,” The Citizen Lab (September 28, 2015), available online at: https://citizenlab.ca/2015/09/international-code-of-conduct/ (accessed on June 10, 2020).

Lolita C. Balder, “Trump approves plan to create independent cyber command,” PBS (August 18, 2017), available online at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/trump-approves-plan-create-independent-cyber-command (accessed on June 10, 2020).

William J. Lynn III, “Defending a New Domain: The Pentagon’s Cyberstrategy,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 89, No.5, September/October 2010, p.101.