The 1962 war between India and China was triggered by the unresolved border dispute between the two young republics that became independent nations in 1947 and 1949 respectively. Australian Journalist Neville Maxwell had been working in New Delhi as correspondent and observed at first hand the drama that ended with a crushing Indian defeat. In 1970 he published a book ‘India’s China war’, this book until today is widely acknowledged as an authoritative analysis of the 1962 war though India has never acknowledged it as such, and learnt no lessons either.

Tracing the historical background of the border conflict and critically analysing modern India’s role in it Maxwell came to the following evaluation: “Hostilities were provoked by India’s reactionary ruling clique which, itself successor to a hateful imperialist regime (British Raj), had been guilty of continuing the latter’s unabashed aggression against a peaceful neighbour worse still at places, Indian troops in the East crossed the McMahon Line into China’s Tibet region. Nor was that all. For towards Peking’s oft repeated offers to negotiate and settle the dispute in a spirit of mutual understanding and mutual accommodation, New Delhi’s attitude was one of arrogance, even intransigence. It laid down impossible pre conditions, including the ridiculous one that China should withdraw from the territory which New Delhi claimed! Provoked beyond patience itself, the Chinese frontier guards fighting in self-defence, wiped out New Delhi’s armed aggression all along the 2,000-mile frontier.”

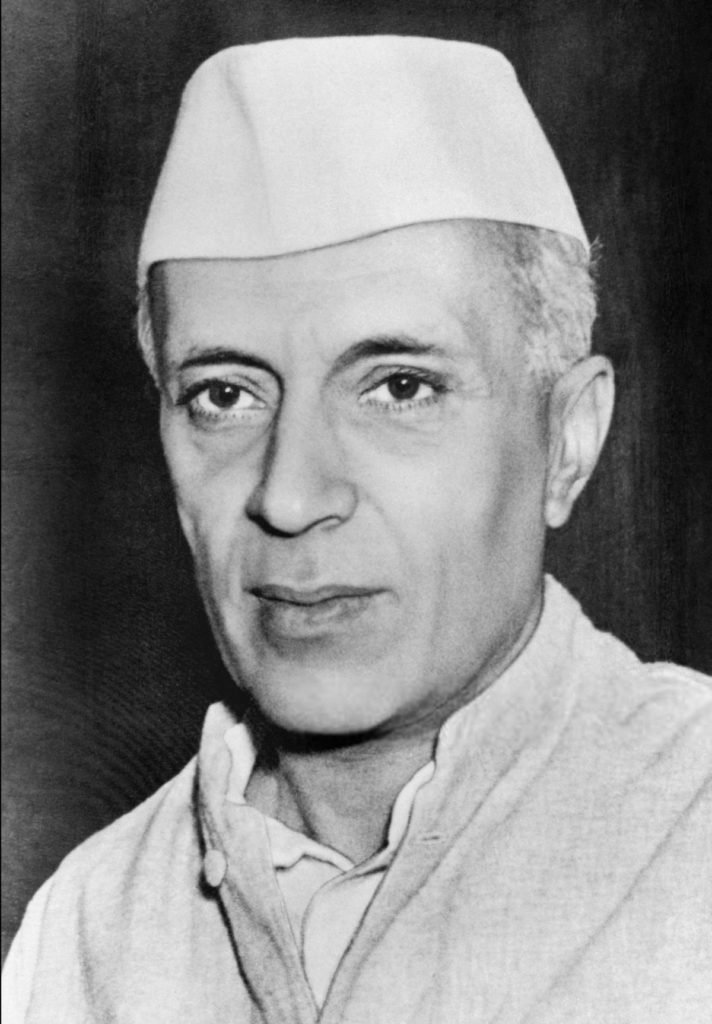

Indian PM Nehru was part of the “reactionary ruling clique”, or at least he listened to the hawks among his advisers. Otherwise is known for having given a lot of public expression to the need of ‘India Cheen bha bhai’ Nehru was of the opinion that independent India was the rightful successor of the British imperial aspirations and powers which made him support a policy of pushing Indian borders as far forward as possible so as to claim full Indian inheritance. Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, British power in India expanded, filling out its control of the subcontinent until it reached the retaining arc of the Himalayas. And from the second half of the 19th century well into the 20th century. British foreign policy in the subcontinent was defined by the fear that Russian expansion could reach the borders of British India and in order to prevent that buffer zones were created to keep Russia away. That was how Afghanistan with a British friendly Amir was kept in the west and the same was intended in the north east of British India. In the middle of the northern border small states and feudatories existed (Sikkim, Bhutan aso) whom the British used the way they used Afghanistan. In the north west and the north east, where no such states existed to act as buffers, the British sought to secure and settle boundaries with China. These they failed to achieve, this failure was to lead to the border war between India and China in the middle of the twentieth century.

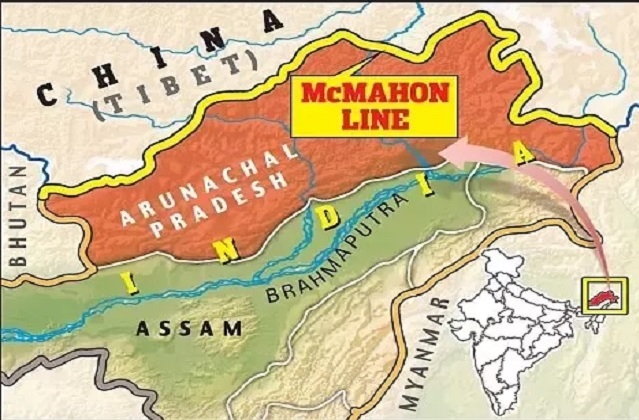

The early 20th century saw the victory of the ‘Forward Policy group’ in London and India which led to adopting of the policy of pushing the outer lines of British-India to include all the territories that were not occupied by the Chinese. Nehru would repeat this policy exactly in the 1950ies. Describing the making of the McMahon Line Maxwell wrote, “The Simla Conference in 1914 is a story in itself, an intricate exercise in diplomacy, power politics, and espionage, played out in the queen of the hill stations at her very prime, on the eve of the First World War.” The main purpose was to loosen China’s hold over Tibet so that it could be used by the British as a buffer. The Chinese were deeply resistant to the proposal for a division of Tibet, no doubt seeing plainly the purpose it was designed to serve, which in their eyes was simply the separation of Tibet or a great part of it from China. Not accepting the defeat of their designs, at the end of the Simla conference instead of signing a tripartite border agreement that settled the border the British signed an agreement with Tibet only thus bringing about the McMahon Line as the north-eastern border of British India. It was never recognized by China because Tibet was part of China at that time and had no power to independently conclude international contracts.

Maxwell is made another interesting point, that the disputed territory in the Himalayas that is triggering so much problems is much easier accessible from China than from India. He concluded that borders should be designed in a way that they are easily accessible and defendable. If using the same argument for Kashmir it is a matter of fact that in 1947 Jammu and Kashmir is still much easier accessible from Pakistan than from India, Indian troops had to be airlifted into Kashmir when the war broke out in 1947. Another argument that he mentioned is that the disputed Indo Chinese border areas are populated though thinly by people that culturally and linguistically as well as religiously are much closer this could be better adjusted to China than to India.

But India did not give any importance to such thinking neither then nor today. The Nehru government officially announced their ‘forward policy’ and rejected all offers of China for a negotiated settlement of the border line by saying that from their point of view all was settled and the matter was not open to negotiation. When the time came that China thought India was now overstepping the limits they gave a bloody nose to India.

The matter is pending since then and from time to time has created low key border conflicts between both neighbours. The main areas of dispute remain two major parts of territory: in the north west the Aksai Chin which belongs to the Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang. The other disputed territory lies south of the McMahon Line was formerly referred to as the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA), and is now called Arunachal Pradesh. In April 2013 India claimed that Chinese troops had established a camp in the Daulat Beg Oldi sector, 19 km on their side of the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Soldiers from both countries briefly set up camps on the frontier facing each other, but the tension was defused when both sides pulled back soldiers in early May. In September 2014, India and China had a standoff at the LAC, when Indian workers began constructing a canal in the border village of Demchok, and Chinese civilians protested with the army’s support. It ended after about three weeks, when both sides agreed to withdraw troops. In 2017, a military standoff occurred between India and China in the disputed territory of Doklam, near the Doka La pass when the Chinese began constructing a road in the disputed area. The stand-off was resolved in August after Bhutan had supported China and India issued a statement saying that both countries have agreed to “expeditious disengagement” in the Doklam region. Since early May 2020 again a similar stand-off is ongoing between the two neighbours. After a brawl between the soldiers in the disputed territory and a high-level meeting between India and China now China has now reclaimed more than 60 square kilometres of that territory that India had patrolled for some time. It seems for the time being the danger of a war has subsided but the matter at hand remains unresolved.

Even though a Chinese spokesperson from the Foreign Ministry has stated that after a meeting on the ground by the senior most commanders in the region a “consensus” has been reached to settle issues peacefully, this is just diplomatic window dressing. The Chinese are in physical possession of territory which India claims in the Galwan valley in Ladakh and is in no position militarily to make the Chinese leave the area. The Indians’ only course of action is to obfuscate reality as best as they can. The time of forward policies, of empires and imperial powers in global power relations is over; China other than many want to believe is not aiming at taking an imperial seat for itself in the global arena. India should finally give up all policies of unilateralism and acknowledge that our globalized world can only survive when we talk and listen to each other and solve the problems.

While Modi Govt (and the Indian Armed Forces) may not like to blunder into another border conflict with China, the hawks in the BJP (and others including retired diplomats and servicemen) and goaded on by the Indian media that has built up such a Bollywood hype about the India’s military might that both the Indian intelligentsia and the masses are baying for Chinese blood (shades of 1962) demanding that all the movie myths become real life and “the Chinese be thrown out!. This will lead to another bloody nose for India.

Contributed By:

Dr. Bettina Robotka

Dr. Bettina Robotka, former Professor of South Asian Studies, Humboldt University, Berlin