The global demand for fresh water resources has escalated dramatically over the last few years, especially in light of rapid population growth and widespread urbanization across the globe. Moreover, as the impacts of climate change and stresses of resource scarcity gain further traction, societies are increasingly hard pressed to find effective and sustainable solutions to their water woes.

Water scarcity has particularly emerged as a highly critical and contentious issue within South Asia, one of the world’s most dynamic regions and home to nearly a quarter of the world population. The subcontinent separated to the north from central Asia by several high mountain ranges the Karakorum, the Hindukush and the Himalayas shares a net of major rivers and their tributaries. Some rivers of Pakistan’s rivers originate in the western mountains, but most of the water flows of South Asia originate from Tibet. Indus, Ganges and its tributaries, Brahmaputra originate in Tibet. Tibet is not only the epicentre of South Asian but of Southeast Asian regional water security. Mekong and Yangtse rivers originate in Tibet as well. Increasing glacial melt in the Tibetan Plateau, combined with changing rainfall patterns across South and South-East Asia, threatens water security for millions of people who rely on the transboundary rivers that originate in Tibet. The annual rate of glacial melt in Tibet is currently seven per cent, which could result in the loss of two-thirds of its glaciers by 2050. Water flows in some rivers like the Brahmaputra have increased due to melting glaciers. River water supply will increase in the short-term but this will only last as long as the glaciers do. Asia cannot rely on increased run-off being a long-lasting phenomenon. Changing rainfall patterns are expected to further exacerbate dwindling freshwater sources.

Climate change, Asia’s rapid urbanisation and population growth rates are placing increased pressure on scarce water resources. China thus takes a central seat in the management of main water resources of Asia including the subcontinent. China is, overall, an arid country and water security has been regarded as an important national security issue for many years. Building dams, irrigation systems and diversion projects thus is considered vital not just for providing water to its 1.3 billion people, but also for ensuring internal political stability. The arid climate in China’s northern regions has created the need to divert water from the Tibetan Plateau into its northern and western regions. China has constructed seven dams along the Mekong River in Tibet and 21 more are planned. Almost 60 million people depend upon the river for food and water security in Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. Any alteration to its flow could have dire consequences for them, including the creation of environmental refugees and water wars.

Same is Brahmaputra. China also has plans for two more dams along it. India opposes the construction of dams along the river because of the effects it will have on India’s own hydropower projects. China’s plans to divert water would damage water flow, agriculture, ecology, lives and the livelihoods of 1.3 billion people downstream in India and Bangladesh.

Bangladesh will experience a serious threat to its water supply by Indian activities upstream the Ganges river as well. The Brahmaputra and Ganges rivers merge in Bangladesh and flow into the Bay of Bengal. India’s damming of the Ganges River has already reduced its flow downstream. Soil salinity in Bangladesh has increased as a result and seriously damaged agriculture. Thousands of Bangladeshis have been forced to relocate to north-east India causing, due to the demographic composition of the area, serious ethnic conflicts the new citizenship law in India is only the beginning. Grim consequences are to be expected downstream in Bangladesh, which has little capacity to challenge them. Further reductions in its water supply could continue to create grounds for internal conflict in the country.

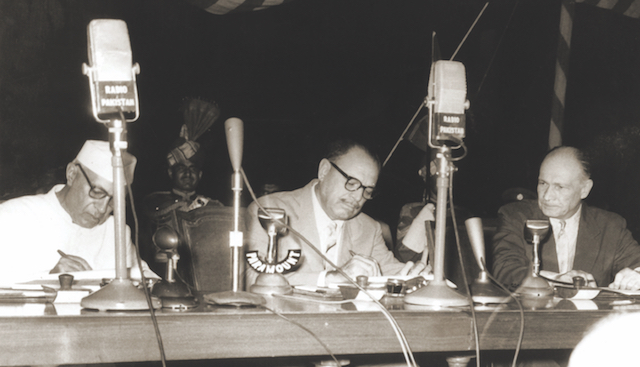

For Pakistan the main trouble is the Indus Waters Treaty signed in 1960 under the auspices of the World Bank. It is a water-distribution treaty between India and Pakistan to use the water available in the Indus System of Rivers located in the north of the subcontinent. According to this agreement, control over the water flowing in three “eastern rivers” of India the Beas, the Ravi and the Sutlej was given to India, while control over the water flowing in three “western rivers” of India the Indus, the Chenab and the Jhelum was given to Pakistan. The stipulations of the IWT have been criticized for many years but with water scarcity hitting the subcontinent India has started encroaching upon the water resources by building new dams like the Kishenganga power project that withholds the waterflow of the river Neelum into Pakistan thus depriving Pakistan and giving India a means to control or even cut off water for Pakistan. In case of flooding India is able to and has already released flood water without precaution into Pakistan thus causing flooding on our side. India despite serious objection on Kishanganga power project on Neelum River and Ratle Hydropower Project on Chenab has gone on completing those projects. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated 330 MW Kishanganga Hydropower Power Station in June 2018. It was completed during the period the World Bank ‘paused’ the process for constitution of a Court of Arbitration as requested by Pakistan in early 2016. The Pakistani request was opposed by India by calling for a neutral expert. The intransigence shown by India and its defiance of international commitments is highly regrettable and proves Indian enmity towards Pakistan. Modi is on record to have threatened to stop the flow of waters of the rivers allotted to Pakistan under the Indus Water Treaty. Given this situation there is even a possibility of a water-related war between India and Pakistan which makes it a national security issue.

Regional power imbalances exist among countries sharing water from Tibetan rivers. Mutual hostility, suspicion and the absence of any legally binding international agreements hinder the likelihood of multilateral success. In 1995, an Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin was signed that acknowledged that the Mekong does not belong to any one state. The objective of the agreement was to ensure sustainable development and co-operation between the downstream countries, yet with the headwaters of the Mekong originating in Tibet, China chose to exercise its territorial jurisdiction and refused to join. Since 1995 globalization has intensified and the impact of climate change has multiplied. It is high time to return to the problem of how to share water resources that are crossing multiple national border. The emerging situation has already undermined the idea of territorial sovereignty of nation states; this development has to be acknowledged and put into use for achieving political solutions for cross-national and cross-regional problems that threaten the livelihood of millions of people. Obviously, the water scarcity and water sharing crises need to get de-politicized which is easy to demand but difficult to do. In a region where territorial problems are unresolved and have led to wars in the past and in a global atmosphere where China is placated as the new imperialist on the stage confidence building measures have to be at the start of any political process. In addition, the countries and governments involved need a sustainable national policy of water management and strong institutions for its implementation. Thus, regional work requires the countries involved to do their homework. The final idea of water management as of managing other cross-national problems is that this is one world and one humanity and depriving others from livelihood takes away my own humanity. (Extracts from a talk being given at Colombo). This is a first part of a two article series.