It would be instructive to learn in this summary assessment that at GHQ, most of the Principal Staff Officers were in complete discord with the General Staff. The Quarter Master General: Maj Gen A.O Mitha, Adjutant General: Maj Gen Khuda Dad and Master General of Ordnance: Maj Gen Eftikhar Janjua, were either not on speaking terms with the Chief of General Staff (CGS), or spoke only if they absolutely had to. Similarly, within the General Staff, the COS and CGS did not see eye to eye on any matter. “The tensions between Hamid and Gul, and Gul and all the other PSOs undoubtedly affected the efficiency of the GHQ,” bemoans Mitha. As can be gleaned, one of the glaring reasons for failure to lay down coherent aims and objectives, and plan and prosecute the war professionally, lay in an utterly disorganised and incoherent higher military leadership then at the helm in GHQ.

Defence of East Pakistan

The Commander of Eastern Command, Lt Gen Niazi had intended to fight delaying actions so as to trade space for time, and then fall back to ‘fortresses’ in important border towns. His baffling orders, however, to continue fighting in the forward posture “till seventy five percent casualties had been sustained,” meant that a completely emaciated and spent force was to fall back and defend the fortresses. With virtually no forces for the defence of Dacca Sector, it was as good as leaving it to Divine intercession, that had purportedly routed the enemies of many a Sultan and Shah in the past. This was despite a reassertion by GHQ, (after an in-situ review by the COS, General Hamid, in early September) that ‘Dacca should be treated as the lynch-pin for the defence of East Pakistan.’

A more pragmatic plan would have focused on embroiling the invading Indian forces in delaying actions from a forward defensive posture, and gradually falling back to the ‘fortresses’ or well-defended strong points in important towns. The defence of Dacca Sector could be left to a dedicated force that was not to be dependent on the fallback of forward elements. Those elements could, thus, continue to attrit and harass the Indian forces in a retrograde battle, as the latter headed towards Dacca. The forward elements could not be expected to execute a timely withdrawal all the way to the Dacca Sector, as their lines of communication would have been severed by the Mukti Bahini saboteurs, as well as by IAF’s air attacks.

The success of such a plan mainly rested on the ability of Lt Gen Niazi to correctly gauge the timing for transition from the counter-insurgency mode to a conventional defensive posture. The forces could, thus, be promptly redeployed and organised for their new tasks in the forward zones and Dacca Sector. There were sufficient indicators in the beginning of November to have spurred the operational reorientation of forces, which could have been completed soon after the Indian incursion started.

With the forces in the forward zones not encumbered with having to defend every inch of the territory, their strength could have been rationalised commensurate with their more focused task, while that of Dacca Sector could have been bolstered proportionately.

Reality dawned rather late on Lt Gen Niazi when on 9 December, he sent a despatch to GHQ bemoaning his plight: “Owing to enemy action and hostility of rebels, cannot extricate force to defend Dacca. Enemy force causing large-scale destruction. Air strikes to be arranged against enemy based around East Pakistan and airborne reinforcements to be dropped to defend Dacca.” That the PAF had been grounded three days earlier had pitiably escaped Niazi’s notice, and clearly indicated his complete loss of situational awareness.

The GHQ must be faulted for failing to outline a broad concept of defence of East Pakistan. In the absence of such a guideline, it was left to a field commander who was not quite renowned in the Army for matters concerning operational strategy. “Professionally, his ceiling was no more than that of a company commander,” laments the former C-in-C of Pakistan Army, Lt Gen Gul Hassan in his memoirs. An equally critical, former armoured division commander Maj Gen Wajahat Husain confirms thus: “Tiger Niazi, an arrogant commander, was known for his limited professional knowledge of low-level tactics and no comprehension of high-level strategy and command.”

Unfortunately, Niazi’s stratagem, which was more bluster and less guile, was considered good enough by the GHQ, where listlessness and confusion prevailed. A fateful oversight by the General Staff whose collective acumen and experience should have been invaluable led to the squandering away of whatever little chance there was to salvage the situation.

When faced with the deteriorating situation in East Pakistan within the first few days of the war, Niazi was falsely assured by GHQ with a cryptic message rich in racial overtones: “Yellow and White help expected from north and south shortly.” Self-deception of this kind reached a climax when GHQ flashed a message to an impatient and desperate Niazi on 12 December, stating that Chinese activities had actually begun! That Yahya had deluded himself with a ludicrous hope of the international community bailing him out, speaks volumes about the bankruptcy of ideas to save East Pakistan.

Own Offensive in West Pakistan

In the GHQ at Rawalpindi, there were two points of view about conducting the main offensive. The CGS, Lt Gen Gul Hassan felt that an offensive spearheaded by II Corps should be launched immediately after an Indian incursion into East Pakistan, concurrent with preliminary offensive operations by the holding formations that are normally required for improving their defensive posture. To Gul, such a scheme would not only keep the enemy guessing about the location of the main offensive, thus retaining the vital element of surprise, it would also help avoid the wrath of the IAF by submerging any large-scale movements of the main offensive “when the entire Western front [would] burst forth like an uncontrollable flood.” Gul was quite sure that the plan was loaded with prospects of achieving the objectives of the main offensive at the earliest, especially if it could develop a pincer in concert with the Army Reserve North. In his view, any delay in launching the main offensive would defeat its very purpose, by allowing Indian forces to complete their mission in the Eastern Theatre, and then, be mustered by the Indian Western Command to be unleashed on to West Pakistan.

Surprisingly, Gul did not dwell on the stratagem required for dislocating the enemy’s strategic reserves, without which own main offensive had little chance of getting past the Indian holding formations at the border.

The Army COS, General Abdul Hamid was of the opinion that launch of the main offensive should be delayed till the preliminary operations had stabilised, and the wind had been read, as it were. Hamid was apprehensive that if the strategic reserves were committed for the offensive operation at the outset, there would be none available to deal with any operational setbacks; it was, therefore, prudent to delay the main offensive till the situation had crystallised. Gul countered his boss by insisting that besides II Corps, there was the separate ARN which could handle any contingency, and it was to be committed for a strategic task only after the main offensive had made some headway.

Like Gul, Hamid also failed to address the issue of how the main offensive could be launched if the ARN was engaged in fire-fighting elsewhere, and was unable to create the necessary conditions for II Corps’ main offensive.

Apparently, both the Principal Staff Officers pinned their hopes on the success of the preliminary offensive efforts in fulfilling the rather daunting task. With none of these efforts designed to threaten any major objective this being outside the scope of such operations it was hard to see how the Indian strategic reserves could be unhinged by something that could not have been more than a minor distraction.

Unfortunately, the twain could not meet, and no consensus emerged amongst the top brass till the eve of full-scale war. Gen Hamid’s cautious approach indicative of a taciturn nature, contrasted with the urgency borne of impetuousness in Gul’s thought process. It was ironical that the C-in-C, Gen Yahya, remained nonchalant about the operational impasse at a most critical juncture; the result was that the Army went to war without a cogent plan of action and kept stumbling from one crisis situation to another.

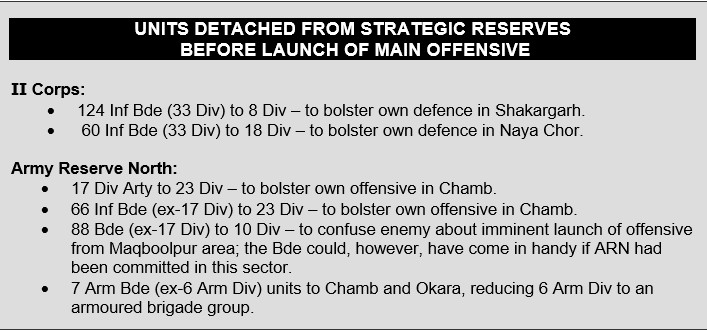

Before the main offensive could be launched, II Corps and ARN had already been denuded of their fighting strength, with their infantry and artillery elements having been rushed to other sectors that were facing critical situations. Gen Hamid’s apprehensions were not totally unfounded, it seemed, after all. A catastrophic situation was averted by not committing the reserves at the outset, as their timely withdrawal, transfer and re-insertion in another sector would have been impossible, subsequently.

With no reserves available for undertaking a meaningful manoeuvre to lure away the Indian strategic formations from Ganganagar-Abohar area, an exasperated GHQ resorted to a desperate ruse one week into the war. ARN’s 88 Brigade (ex-17 Division), was despatched with bridging equipment to Maqboolpur on the banks of River Ravi, seemingly the advance party of a surprise offensive that was about to undertake a river crossing. The Indians either did not notice the new arrival, or simply remained unmoved. This left the GHQ much befuddled for not achieving any results, despite detaching yet one more formation from its reserves, rendering them operationally useless for their primary task.

Going by the number of units permanently detached from the strategic reserves, it can be seen that, at a minimum, Pak Army’s deficiency was equivalent to one infantry division (i.e. three infantry brigades and an artillery brigade). Any plans to overcome such an operational shortcoming at the expense of either of the two strategic reserves, clearly meant that the main offensive was a non-starter. Additional reserve troops for the vulnerable formations like 8 Division (Shakargarh Sector) and 18 Division (Thar Sector), on whose turf strong enemy offensives were inevitable, should, therefore, have been adequately catered for at the outset. Unfortunately, as no collective field exercises had been held at Division or Corps level since 1969 due to involvement of the senior Army echelons in Martial Law affairs, such operational shortcomings of field formations remained largely unnoticed, and hence, unremedied.

Assuming that II Corps and ARN had somehow been able to maintain their integrity, would these formations have been able to accomplish their assigned tasks before Lt Gen Niazi’s Eastern Command eventually gave up? After all, it was important that GHQ not be disheartened by bad news from the Eastern Command Headquarters while in the middle of a crucial campaign in the West.

By most estimates, it would have taken at least two weeks for ARN’s counter-offensive in Shakaragarh to roll back the Indian offensive, and another one week before it re-oriented itself and started pushing towards a vital Indian objective. If all went according to plan, the objective had to be threatened impudently enough for some of the Indian reserves in Ganganagar-Abohar to scamper northwards to provide relief. That such a displacement of Indian strategic formations could actually take place while their originally assigned sector was left vulnerable, beggars belief, but may be assumed for purposes of an academic discussion. It can, thus, be seen that something like three weeks were required before Pak Army’s main offensive could materialise. Once launched, however, the morale in Niazi’s Eastern Command would have been buoyed immensely, and with a dedicated fortress defence plan in place, it might not have been altogether impossible to hold out till the offensive in the West had made some worthwhile gains.

The issue of the how the IAF would have dealt with a hunkered down force defending Dacca Sector remains moot. Nonetheless, with no extensive ground manoeuvres involved which could have greatly exposed the troops to air attacks, it can be surmised that they would have been dug-in, well-concealed and thus, far less vulnerable. The Pak Army AAA batteries were also largely intact, and there is every reason to believe that they could have contributed immensely in the effort to hold out longer.

Higher Direction of War

The President of Pakistan, Gen Yahya Khan, wore three additional hats including that of the Chief Martial Law Administrator, the Defence Minister, and C-in-C of the Army. Thus, to all intents and purposes, decision-making, with unchecked powers in all four domains, rested with him. With no consultative body to render sober advice, the country was at the mercy of his judgements and actions.

Based on his past association with Yahya, Gul recalls him to be “professionally competent, decisive, confident, and possessing a high IQ, a remarkable memory and sharp perception.” Despite these impressive attributes, the burden of soldiering and governing at the same time, especially the latter sphere in which wily politicians had him twisted around their fingers, eventually proved too much for him.

In a move which was understandably a personal expedient, Yahya had retained Gen Abdul Hamid, his senior batch-mate, as the Army COS. Not willing to relinquish his real power base as the C-in-C, Yahya expected Hamid to play second fiddle which, as a superseded officer with a lackadaisical outlook, the latter did not find too intolerable to accept. The resulting situation was intensely detrimental to the Army for whose interests, Hamid had little inclination, and Yahya had little time.

With the war looming, Yahya did, however, find time to spell out his thoughts on the course of action he wished to adopt, in the fast aggravating military situation. Summing up a discussion after presentation of the National Strategy Paper by the National Defence College students in early November, Yahya declared, much to the surprise of officers of various syndicates, “I am not so stupid as to go to war with India. I will do my best for a political situation to avoid war.” The statement would have been considered a stroke of genius if it had come six months earlier, but it was dreadful to learn that he had failed to read the ill winds blowing from India, which were now gathering into a vicious storm. Quite evidently, Yahya was out of his elements at this critical stage, had not kept himself abreast of the goings on, and was clueless about what to do. Instead of turning dovish, as if he was playing to a gallery of Western press reporters, he should have unequivocally outlined the broad contours of his strategy for war fighting at the highest seat of military learning. His statement was as confusing as it was defeatist; in fact, if one reads between his seemingly sagacious lines, Yahya had already lost the will to fight.

End Notes

Unlikely Beginnings, Mitha, Maj Gen A O; Oxford University Press, Karachi, 2003; page 323.

Witness to Surrender, Salik, Siddiq; Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1977; page 128.

Memoirs; Khan, Lt Gen Gul Hassan; Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1993; page 326.

Ibid; page 274.

1947 Before During After, Husain, Maj Gen Syed Wajahat; Ferozsons (Pvt) Ltd, Lahore, 2010; page 244.

Memoirs, Khan, Lt Gen Gul Hassan; Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1993; page 328.

1947 Before During After, Husain, Maj Gen Syed Wajahat; Ferozsons (Pvt) Ltd, Lahore, 2010; page 244.