The earlier decision to postpone the National Assembly session scheduled for 3 March had been met with extreme derision and wide-spread anger in East Pakistan. Hartals (general strikes) all over the province were ordered by the Awami League, and Mujib made it clear that the postponement decision would not go unchallenged. Behind the scenes, though, he again pleaded with the Governor, Vice Admiral Ahsan, for a fresh date for the assembly session. Mujib’s request was passed on to the Army Chief of Staff (COS), General Hamid, but instead, the top brass took a thoughtless decision to sack the Governor, and Lt Gen Yaqub was asked to take over that office also on 1 March.

Press censorship was imposed, followed by a curfew in Dacca. Mujib reacted by closing all doors on further negotiations and launched what he termed a ‘non-violent non-cooperation’ movement. The Bengali staff of PIA was the first to respond by refusing to handle flights, which brought troop reinforcements from Karachi to Dacca. Charged crowds attacked the Government House in which six people were killed in clashes with troops on guard duties. On 2 March, Mujib issued a statement calling on “all sections of the society, including government servants to rise against the unlawful government and recognise peoples’ representatives as the only legitimate authority.” Lt Gen Yaqub talked to Mujib on telephone asking him to withdraw the statement, but a hostile Mujib out rightly refused to oblige. The law and order situation continued to worsen. Reports of casualties poured in from all parts of the East Pakistan, with non-Bengalis suffering the worst at the hands of rampaging mobs.

President Yahya initially maintained a nonchalant attitude in the face of constant pleading by Lt Gen Yaqub for some decision, as the situation deteriorated rapidly. Yahya finally decided to call a meeting of all politicians in Dacca on 10 March, but Mujib reacted furiously by refusing any more ’round-table conferences.’ Yahya spoke to Mujib on telephone, and tried to talk him out of his obduracy. The result of the conversation became clear only when Yahya called Lt Gen Yaqub on the night of 4 March, and informed him that the planned visit to Dacca had been called off. An exasperated Lt Gen Yaqub immediately called the President’s Principal Staff Officer (PSO), Lt Gen Peerzada in Rawalpindi and told him that he would be sending in his resignation the following day. Before the resignation reached the president, Lt Gen Tikka Khan, the Martial Law Administrator of Punjab and Commander IV Corps, had been already been assigned to replace Lt Gen Yaqub as a three-hatted Commander of Eastern Command, Martial Law Administrator, and Governor East Pakistan.

The ‘non-violent’ movement that Mujib had promised was getting more and more violent. A particularly bloody day-long battle on 3 March between the Awami League terrorists and unarmed non-Bengalis in Pahartali near Chittagong resulted in 102 deaths. In Dacca, no one felt secure. Most of the well-off non- Bengalis had sold off their house-hold effects for a pittance, and purchased tickets to fly off to Karachi. The poorer ones went into hiding or sought refuge in the cantonment areas that were relatively safe.

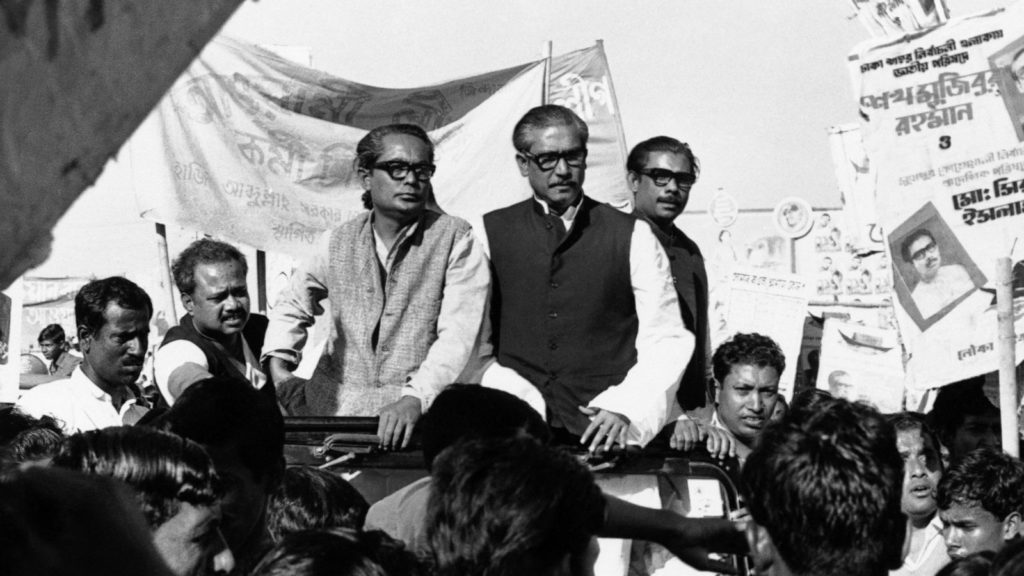

On 6 March, the Awami League went into session to take a final decision on the unilateral declaration of independence of Bangladesh. Getting wind of what might follow, President Yahya called Mujib, advising him not to take a hasty decision, and assured him of honouring his (Mujib’s) aspirations and commitments to the people. Yahya also promised to visit Dacca soon. The declaration of independence was perhaps averted as a result of the timely call, much to the satisfaction of the Martial Law Headquarters in Dacca. The same day Yahya announced that the National Assembly would meet on 25 March. Mujib responded to the announcement with four precondition’s for attending the session: 1) Lifting of Martial Law 2) Return of Army to the barracks 3) Transfer of power to the people’s representatives 4) A judicial inquiry into the killing of Bengali people.

General Yahya decided to make one last attempt at finding a political solution to the deadlock and flew to Dacca on 15 March. Soon after arrival, he asked his military commanders for a situation report. At the end of the briefing, Yahya muttered, “Don’t worry. I will line up Mujib tomorrow will give him a bit of my mind. Then if he doesn’t behave, I’ll know the answer.” While the Generals in attendance were dumbstruck, the PAF’s Air Officer Commanding (AOC), Air Cdre ‘Mitty’ Masud sought permission to say something. After Yahya nodded a go-ahead, Mitty opened up, “Sir, the situation is very delicate. It is essentially a political issue and needs to se resolved politically, otherwise thousands of innocent men, women and children will perish.” Nodding his head in fatherly fashion, Yahya replied, “Mitty, I know it I know it.” A few days later, the highly decorated 1965 War hero, Air Cdre M Z Vasud was relieved of his duties.

No Way Out

After a rather cold informal meeting the following day, it was evident that the time for accommodation of any sort between Yahya and Mujib had passed. Yahya was snug with his hold on absolute power while Mujib too seemed to exude complete control due to the massive mandate of the people of East Pakistan.

During the formal talks on 17 and 18 March, neither side was willing to compromise, which came as no surprise. The talks failed miserably, with Yahya and Mujib emerging dejected and irate over the fiasco. The Awami League had insisted that Martial Law be lifted and power transferred immediately to Awami League, while two independent committees of the National Assembly chalked out ways to promulgate a new Constitution agreeable to both the wings. Yahya agreed to the Awami League proposal on condition that Bhutto had no objection to it. This, despite the grave threat to Yahya’s regime as it would lose legal sanction with the removal of martial law. As for Bhutto, he was averse to any arrangement that saw him out of power, but, so as not to be seen as a spoiler, he agreed to visit Dacca nonetheless.

On arrival in Dacca on 21 March, Bhutto was briefed by Yahya about Awami League’s proposal for power transfer. Bhutto reacted by drawing Yahya’s attention to the impropriety of approving the scheme without full knowledge of the people. He was of the opinion that “two or more political leaders could not ignore the existence of the entire Assembly vested with constitutional and legislative power.” He also told Yahya that he saw ‘seeds of two Pakistan’s in the Awami League’s proposal.

Behind the scenes, an apprehensive Yahya had conveyed to Lt Gen Tikka to ‘be ready’, implying plans and preparations for military action in case the political talks failed.

23 March, regularly celebrated countrywide as the Pakistan Resolution Day, saw tumultuous rioting all over East Pakistan. Pakistani flags were burnt and replaced with those of Bangla Desh, while Quaid-e-Azam’s portraits in offices were replaced with those of Mujib-ur-Rahman. Joi Bangla (Long live Bangla Desh) slogans could be heard everywhere. It was quite clear that the writ of Martial Law was weak, and a parallel government, supported by the people, was in control in East Pakistan.

The following day, Awami League, proposed the formation of two Constitution Conventions to draw up separate Constitutions for East and West Pakistan. The National Assembly was to subsequently assimilate these Constitutions into a framework for the ‘Confederation of Pakistan. Yahya and Bhutto met soon after the announcement, and concluded that the Awami League had shifted radically from its demand of maximum provincial autonomy, to the outright disintegration of Pakistan. The hint of a tenuous link between the two wings in the Awami League offer was seen by Bhutto as a hindrance to his quest for absolute power a departure from his earlier position of sharing power under the so-called udhar tum, idhar hum formula, which was no less a confederal arrangement. Yahya, on the other hand saw it as the first step towards secession under his watch, and may have apprehended a severe reaction within the Army, as well as the masses in West Pakistan. Matters had come to such a pass that use of force to keep the country united seemed to be the only remaining option for Yahya.

Military Crackdown

On 25 March, Yahya and his aides quietly flew back to West Pakistan, followed by Bhutto a day later. As ominous clouds gathered over the horizon, it was clear that the time for politics was over.

The military had planned to conduct Operation ‘Searchlight’ starting at 0100 hrs. on 26 March, by which time General Yahya would have safely landed in Karachi. Maj Gen Rao Farman Ali, the advisor on civil affairs was put in charge of operations in Dacca and its environs, while Maj Gen Khadim Hussain Raja, General Officer Commanding (GOC) 14 Division, was given charge of the rest of East Pakistan.

Some of the more important tasks assigned to Farman’s subordinate, Brig Jehanzeb Arbab, (Commander 57 Brigade), included disarming of about 5,000 personnel of East Pakistan Rifles, disarming of 1 ,000 policemen at the city’s Police Lines, neutralisation of Awami League strong points inside Dacca University, and capture of Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rahman (code-named ‘Big Bird’). Additionally, combing operations and show of force was to be conducted, wherever required.

The operation in Dacca was over by first light, with all objectives achieved. The ‘Big Bird’ was in the cage, and was whisked off to Karachi three days later. The casualty figures of the Bengalis, especially at the University, remain moot. While the Army sources estimated around one hundred deaths in the University area, Bengalis insisted that these ran in thousands.

The main task of securing the rest of East Pakistan with a single army division was not an easy one. In rebel strongholds The Chittagong, Kushtia and Pabna were particularly formidable and well-defended, and needed to be neutralised promptly before the rebels went on the rampage against the non-Bengalis.

Chittagong had just one battalion with 600-odd troops to fight off an estimated 5,000 rebels. Reinforcements from the brigade headquarters at Comilla, including an infantry battalion and a mortar battery, were blocked by the rebels after blowing up of a bridge enroute. All attempts to make headway towards Chittagong were thwarted, and eventually, contact was lost with the relief column. The GOC himself undertook a search of the column from a helicopter, braving intermittent fire and several hits, but to no avail. A detachment of commandos was also flown in from Dacca to search for the column, but soon it came under rebel cross fire and took substantial casualties. i When the Officer Commanding of 24 FF fell in action, the Brigade Commander (53 Brigade) at Comilla, Brig Iqbal Shafi, himself took charge of the battalion and was able to break the rebel resistance not long after-wards. The way to Chittagong was cleared, but unfortunately, the troops were too late to prevent a horrible massacre of unarmed non-Bengali men, women and children at lspahani Jute Mills near the edge of the city.

The important tasks in Chittagong included destruction of radio transmitters that had been spewing virulent anti-Pakistan messages, as well as the neutralisation Pakistan Rifles of East Headquarters and Reserve Police Lines. The latter two locations had a strong presence of trained saboteurs, and were reported to have been heavily stocked with weapons. After two abortive and costly attempts by a commando detachment to blow up the radio transmitters, PAF Sabres were called in to do the job, which was easily accomplished. ii

The East Pakistan Rifles Headquarters was attacked with a couple of tanks, heavy mortar battery, as well as unconventional fire support from the destroyer PNS Jahangir and two gunboats Rajshahi and Balaghat. After a raging battle that lasted for three hours, the target was destroyed and the rebels subdued.

The defenders at the Police Reserve Lines could not face Pak Army’s battalion-sized onslaught and promptly vacated the area.

While the main operations in Chittagong were over in five days, mopping up continued into the first week of April.

In Kushtia, the task for the Army was to maintain security and establish own presence with the help of a company detached from its battalion headquarters at Jessore, 55 miles away. On 28 March, the local Superintendent of Police informed the Company Commander that an attack on the town by rebels was imminent. The attack commenced with heavy mortar firing early on the morning of 29 March. Troops of an East Bengal battalion joined by the Indian Border Security Force charged on the police armoury occupied by Pak Army troops. In the next few hours, twenty soldiers had fallen. The company headquarters, as well as posts at the telephone exchange and VHF station were also attacked by the Bengali-Indian combine, resulting in heavy casualties. Desperate requests for reinforcements were denied due to other commitments, and air support had to be called off due to poor visibility.

Kushtia was abandoned, and 65 surviving soldiers out of 150 were driven out in a convoy to Jessore. Enroute, a deadly ambush cut down all but nine soldiers who managed to escape, only to be rounded up and subjected to a bar- baric end. The ill-prepared company had been virtually wiped out in what was the worst disaster faced by the Pakistan Army during Operation ‘Searchlight’.

In Pabna, the task was not much different from the one at Kushtia, being mostly show of military presence in the area, by a lightly armed company of troops.

Some important vulnerable points like the power house and the tele-phone exchange were also to be defended against the rebels. A costly mistake was made in wrongly assessing the strength of the rebels in the area. This realisation came too late when the rebels carried out a surprise raid on the telephone exchange in which 85 troops were martyred. The remnants were evacuated by a relief party from Rajshahi, but were met with heavy resistance as they fought their way out. The column reached Rajshahi with just 18 survivors; 112 had been martyred in the operation.

Operation ‘Searchlight’ was deemed to have helped achieve full control over much of the province by the end of April. While the Bengalis claimed that their casualties ran in hundreds of thousands in less than a month, Pakistan Army sources insist that rebel deaths did not exceed four figures. India had good reason to inflate the numbers to paint Pakistan Army in bad light in the eyes of the international community, an exercise in which she succeeded resoundingly. Expulsion of foreign press prior to the operation did not help matters either, and was only too pleased to parrot India’s line on the subject.

Full-blown Insurgency

While Operation ‘Searchlight’ was underway, two more Army divisions (9 and 16 Divisions), as well as additional paramilitary forces, were flown in from West Pakistan. These forces were lightly armed, and their heavy equipment was left behind. A new Commander of Eastern Command, Lt Gen A A K Tiger’ Niazi was also posted in, and he had three new GOCs of the three divisions for conducting counter-insurgency operations.

The Indian government had, meanwhile, declared its full support to the rebels, having perceived a distinct possibility of Pakistan’s breakup. The Director of Indian Institute of Strategic Studies, Krishnaswamy Subrahmanyam gave heft to that perception when he brazenly suggested at a symposium to destroy Pakistan: “What India must realise is the fact that the breakup of Pakistan is in our interest, and opportunity the like of which will never come again.” iii He called it a ‘chance of a century’ to destroy India’s enemy number one.

India started a crash programme of military preparations including reorganisation and reequipment. On the diplomatic front she went all out in creating a favorable world opinion, as well as getting erstwhile Soviet Union’s commitment to help in the impending military action. lV the presence of Bengali refugees and their plight was also exploited advantageously.

The most consequential action by India was the formation of an organised, well-trained and well- equipped rebel force, to thwart Pak Army’s efforts in fighting the insurgency. The Mukti Bahini (freedom fighters) force was cobbled up with Bengali defectors from the army and para-military forces, students and able-bodied volunteers. Their task, as recalled in India’s Second Liberation by Pran Chopra, was: “Deployment in their own native land with a view to initially immobilizing and tying down the Pakistan military forces for protective tasks in Bengal, subsequently by gradual escalation of guerrilla operations, to sap and corrode the morale of the Pakistan Forces in the eastern sector, and finally to avail the cadres as ancillaries to the Eastern Field Force in the event of Pakistan initiating hostilities against us. v

With a constantly growing number of training camps in India, as many as 100,000 Mukti Bahini had cycled through training courses by end of November 300 frogmen had also been trained by India to under-take sabotage operations against shipping and riverine craft.vi

Pak Army had a total of 45,000 troops, including 11 ,000 paramilitary forces and police. Vii It also had additional support of about 50,000 Urdu-speaking Biharis and some sympathetic Bengalis under the support of an umbrella organisation called Razakars (volunteers). While the Razakars had been fired by patriotic fervour, they did not have proper training to transform their zeal into anything worthwhile. They could hardly conduct operations independent of the Pak Army.

Pak Army earnestly started active counter-insurgency operations in April. The main focus was on maintaining occupation of border posts, and controlling major towns. Rebels followed hit and run tactics, and could not be countered as they disappeared before the Pak Army arrived on the scene. This modus operandi of the Mukti Bahini continued incessantly for many months. With time and ceaseless Indian support their methods became more well-planned, and the rebels became more audacious in their attacks. Bridges, railway lines and electric power stations were the preferred targets. For the Pak Army, fighting an insurgency spread over more than 55,000 square miles was a tall order. Besides, being involved in a prolonged insurgency without any relief resulted in indifference and apathy setting in.

The writing on the wall was clear: the population of East Pakistan was not going to stop short of an independent Bangla Desh, as the West Pakistani power brokers had nothing to offer that could meet their aspirations. Retracting at this stage, when too much blood had been spilt, would have been seen by the Bengalis as an insult to their dignity. Sadly, the time for reconciliation was past.

General Yahya seemed completely afflicted by inaction and inertia over the nine months spanned by the insurgency. His efforts at some sort of reconciliation were confined to superficial measures, including replacement of Lt Gen Tikka Khan with a civilian Governor, to assuage the feelings of the Bengalis who saw Tikka as a tyrant. A former dentist, trade union leader, and elderly politician, DRAM Malik was sworn in on 3 September. A day later, general amnesty for ‘miscreants’ was announced but there was no mention of the release of Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rahman which made it appear meaningless to the Bengalis. Yahya’s actions were, decidedly, too little, too late.

A Chance of a Century for India

While preparing for a military intervention in East Pakistan, India continued with shrewd diplomatic efforts in parallel. Notably, she signed the euphemistically dubbed Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Co-operation on 9 August 1971. Her diplomatic offensive centred around the ‘massive humanitarian problem’ of refugees who had fled to India because of the civil war in East Pakistan. It also helped assuage any apprehensions of a possible wider conflict, especially with regard to US and China, whose beleaguered ally, Pakistan, could have clamoured for help. In any case, the US was unwilling, and China unable to do much to avoid a conflagration.

The Indian military, in the mean-time, found enough time to prepare for war on two fronts viz, West Pakistan as well as East Pakistan, the latter being considered as the main theatre. Equipment and man-power shortfalls were speedily addressed, and war plans adequately reviewed.

War preparations on the Pakistani side were seriously con-strained by shortfalls in the Army’s fighting formations. The move of two infantry divisions from West Pakistan was clearly a short-term response to the deteriorating situation in East Pakistan; it gravely altered the balance of forces in the West, the main theatre of war. Any operational reverses that might occur were to be redressed the strategic by denuding this reserve. Unfortunately, meant that the very foundations of a Pakistani military response had been utterly weakened.

While the insurgency within East Pakistan continued without let, India started artillery shelling on the border outposts in late June. This activity increased in the following months, with as many as 2,000 rounds falling daily. viii on the one hand, it served the objective of controlled escalation by India, while on the other, it helped the Mukti Bahini in occupying many salients and enclaves, as these became indefensible under constant fire. By the time of General Yahya’s address to the nation on 12 October, in which he declared that every inch of the sacred soil of Pakistan would be defended, 3,000 square miles of border area had already gone under Indian control. ix

India had carefully assessed that Pak Army troops in East Pakistan were tired of fighting an insurgency for over eight months, and their morale was not at its best. Indian Army had the numbers to overwhelm Pak Army troops three times over, and had adequate mobility and logistics support to make a fast run for Dacca. In West Pakistan, India enjoyed numerical superiority, especially in the Desert Sector where it was overpowering. Her defences were strong in all sectors, and she was confident of stopping any Pakistani foray, were Pakistan to attempt capture of vital territory as a sop for the loss of East Pakistan.

As for the Pakistan Air Force, India saw it mostly in a supporting role for Pak Army, and if the latter’s design could be stymied through deft planning, the aerial battlefront was not seen as a major threat to her designs. As war clouds appeared over the sub-continent, India found it opportune to act on Subrahmanyam’s advice to avail the chance of a century. Sadly, at this stage, there was hardly a way out of the morass that Pakistan found itself in but to fight, however best as was possible.

(Part I of this article appeared in the May issue of Defence Journal)

End Notes

i 16 commandos were martyred in this action.

ii 13 commandos were martyred in this action.

iii The symposium was organised by the Indian Council of World New Delhi. In Affairs Subrahymanyam’s speech was reported by The Hindustan Times, New Delhi, 1 April 1971.

iv The Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Co-operation was signed on 9 August 1971. 155.

v Page 155.

vi Pakistan Cut to Size, Manekar, D R, Delhi; page 133.

vii This figure is quoted by Lt Gen Niazi in his book, The Betrayal of East Pakistan, Chapter 14, page 237.

viii Witness to Surrender, Salik, Siddiq; Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1977, page 116.

ix lbid.