While charting out a constitutional plan for the Muslims of India, the All-India Muslim League. proposed in the Lahore Resolution of 23rd/ 24th March 1940 that geographically contiguous units, as in north-western and north-eastern India (which were confusingly also called regions, areas and zones in the same breath), should form independent states in which the constituent units would be autonomous and sovereign. As is quite evident, the resolution implied two independent states, each having a loose confederal structure for its constituent units (or provinces).

In the event, did the founding fathers renege on the agreed plan of more than one independent Muslim state? It would almost be heretical for Pakistani minds to think that it was anything but a typographical error, but it seems that some expediency compelled a revision of the original resolution. Thus, while the amended resolution laid the foundations of an independent state, it also sowed the seeds of secession in a constituent unit (East Pakistan) by overlooking its “distinctive culture, language, and a history of being1 in effect an outsider in South Asia.”2

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah was aware that the Muslim League had a very narrow base of support in Punjab, mostly amongst students. It had not held power in Punjab before Partition, and had virtually ceded leadership on Muslim issues to the inter-communal Unionist Party since 1922. It had managed to win just one seat in the provincial assembly in the 1937 elections. In the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), despite being the largest Muslim majority province (almost 92%), the Muslim League was unable to make inroads in the self-serving politics of the province. It had lost every single election until the June 1947 referendum in favour of joining Pakistan. NWFP indisputably had the strongest ‘contrarian streak’3 in the Muslim majority areas, which manifested itself in rejection of the idea of control from a remote national Centre. In Sind, the landlords and the spiritual leaders only came around to supporting the independence movement with some hesitation, though its legislative assembly eventually became the first to approve the Lahore Resolution. Under such shaky and uncertain conditions, it was important to gamer support of East Bengal where the League had done well on a Muslim communal platform in the 1937 elections. After all, the Muslim League began in Dacca in 1905, reflecting East Bengal’s proud history of Muslim separatism.

For Jinnah the pragmatist, a demand for two independent states would have meant that none might be achievable, given the weak electoral standing of Muslim League at the time of the Lahore Resolution. The resolution was, thus, belatedly amended by a small Legislators’ Convention in April 1946 in Delhi; it mentioned a united state of Pakistan.

To assuage persisting doubts in the minds of some Bengali Muslim members who insisted on a full session approval, the Muslim League leadership adopted a ‘memorandum of minimum demands’ on 12 May 1946, stating, “After the constitutions of Pakistan Federal Government and the provinces are finally framed by the constitution making body, it Will be open to any province of the group to decide to opt out of this group, provided Wishes of the people of that province are ascertained in a referendum to opt out or not,”

Overruling the clause calling for independent states did indeed help create a united Pakistan, but not to be forgotten was the ‘memorandum of minimum demands’ of 1946, which had clearly sanctioned secession if a province so desired. It was thus incumbent on the Centre to carefully address the aspirations of its Bengali compatriots who had been historically at odds with any central authority. In retrospect, a semi-autonomous formulation between the two provincial units similar to the way Peoples’ Republic of China and erstwhile Soviet Union managed their ethnically and linguistically disparate peoples could have been workable models. How long such an arrangement could continue to ward off any fissiparous tendencies in the unit (or province) is a moot question, but would have largely depended on the degree of accommodation the Centre was willing to live with.

Language Issue

Soon after gaining independence, the issue of a state language occupied the fledgling government of Pakistan. Believing that a single language was needed for a country to remain united, Urdu was officially declared as the state language of the Dominion of Pakistan on 25 February 1948. It has to be noted that this step overlooked a resolution of All-India Muslim League (Bengal) which had rejected the idea of making Urdu as the lingua franca of Muslim India during its 1937 Lucknow session.

Omission of Bengali as one of Pakistan’s state languages predictably resulted in riots in East Bengal (as it was known until 1956). Following a complete general strike in Dacca on 11 March 1948, the Quaid decided to explain the rationale of one state language during his first and last visit to Dacca after independence. On 21 March 1948, during the civic reception, he stated, “There can be only one state language if the component parts of this state are to march forward in unison, and in my opinion, that can only be Urdu.” Three days later, the Quaid repeated his stance while addressing students at Dacca University, much to their consternation. Quaid’s declaration caused considerable resentment amongst the Bengalis who were 56% of the country’s population, as compared to 44% of the combined four provinces that formed the western wing. Of the latter, only 7% spoke Urdu, the rest communicating in their regional languages.

The government of Pakistan based in the then capital of Urdu speaking Karachi, considered Urdu as a vital element of Islamic heritage and culture. The language, though based on Hindi’s Prakrit precursor, had developed under Persian, Arabic and Turkic influence, and even its Perso Arabic Nastaliq script was somehow fancied as ‘Islamic.’ In contrast, Bengali, with its Devanagari script that it shared with Hindi was seen as linked to Hindu culture. To get around this problem, even a halal version of Bengali in Arabic script was proposed by the government’s East Bengal Language Committee, but its official report never saw the light of the day.

Because of the decision regarding Urdu as the state language, a movement demanding Bengali as another state language started in earnest in East Bengal. The movement not only laid the foundations of Bengali nationalism, it heightened the cultural animosity between the two wings of Pakistan. Matters came to a head when language riots led to the death of five students in Dacca on 21 February 1952, a day that is considered as a watershed in the relations between the two wings. The sad event catalysed various Bengali nationalist movements in its wake, including the Six-Point Programme discussed hereafter.

After much squabbling and need less loss of blood, the Constituent Assembly finally voted in support of Bengali as a second state language alongside Urdu on 7 May 1954. The Constitution was accordingly amended in 1956, finally, but much had been lost by way of goodwill between the two wings of the country.

Socio-Cultural Divide

Bengal had a rich culture based on literature, poetry, music, song and dance. The Bengalis were inspired by the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), a secular poet and writer. To the West Pakistanis however, East Bengalis’ adulation of Tagore was somehow inconsistent with an Islamic Pakistan. Tagore’s works were banned from government-con trolled radio and television because they ‘promoted secular Bengali nationalism.’4 Even the East Bengali nationalist poet, writer and musician, Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899- 1976), failed to find admiration in West Pakistani literary circles. The people of West Pakistan were endeared to Allama Muhammad Iqbal, a poet with a pan-Islamic vision, and an inspiration behind the Pakistan Movement. Any possibility of syncretism of the varied philosophies and ideals was, in large part, obstructed by the language barrier. Attempts at cultural assimilation were tried out through various half baked methods, but the schism remained wide and unbridgeable.

While the literacy rate of both wings was dismal at the time of partition (remaining so for decades thereafter), the West Pakistanis found themselves better qualified for the civil services. Postings of West Pakistani civil servants to East Pakistan were, thus, a common practice. The Bengalis saw this as a perpetuation of colonial rule in a new form. West Pakistani bureaucrats ordering the Bengalis around was the last thing that could be endured by the latter. The result was an unintended social divide that manifested itself in a ‘master-subject’ relation ship of sorts, rather than as equals.

Despite the seeming social divide, the political front remained less affected as borne by the remarkable fact that in the early to mid-fifties, Pakistan’s second, third and fifth Prime Ministers were from East Pakistan.5 It is another matter that none of them completed their tenures, either due to dissolution of their governments or due to differences with the Governor General.

Perceived Lack of Development

A sizeable share of Pakistan’s foreign exchange earnings came through the export of cotton and jute, the latter growing exclusively in East Pakistan. Bengalis complained that the development projects set up in East Pakistan were few and far between, and not at all commensurate with their contribution to the national exchequer. Awami League, the mouthpiece of the Bengalis, went to the extent of claiming that for 60% of the export earnings, East Pakistan’s share in development projects was only 25%. The contention seems far-fetched if one were to note that several major industrial projects were first initiated in East Pakistan. The world’s biggest jute mill was established in Narayanganj, East Pakistan in 1951 by the industrial con glomerate of Adamjee Brothers who contributed a 50% share capital, while the rest was sanctioned by the government through the Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC). Pakistan’s first paper mill was set up in Chandargona, East Pakistan by PIDC in 1953. Many years later, Pakistan’s first steel mill was also set up by PIDC in Chittagong in 1969. Clearly, industrial development in East Pakistan was not as dismal as painted out by the Awami League.

A Reactionary Six-Point Programme

The Awami League’s Six Point election manifesto was obsessively fixated with devolution of powers from the federation to the provinces, to an unprecedented extent. The federal subjects included only foreign affairs and defence. Two mutually convertible currencies, or as an alternative, a single currency subject to establishment of separate regional Federal Reserve Banks for the two wings of the country were proposed to be established, ‘to pre vent transfer of resources and flight of capital from one region to the other.’ Fiscal policy was to be the responsibility of the federating units which would provide the requisite revenue resources to the federal government according to a laic down formula. More seditious was the proviso for separate accounts o’ foreign exchange earnings of each of the federating units, which were to be maintained under control o’ their respective governments. This stipulation entailed sanctioning the federating units to independent! negotiate foreign trade and assistance with other countries. Finally, the government of each of the federating units was to be empowered to maintain a militia or paramilitary force for ‘effective contribution towards national security.’

A latent problem of the Six-Point Programme was that it had unintended consequences for the federating units in the western wing.6 It implied, for instance that all four federating units (provinces) in the west ern wing along with the eastern wing could chart out their own fiscal policy, and could conduct foreign trade and negotiate financial assistance from international donors. There was also the ripe possibility of each of the federating units of the western wing demanding its own Federal Reserve Bank which would have virtually amounted to independence.

A cursory glance at the Six-Point Programme indicates that the cause of disagreement was essentially the purported flight of capital from East Pakistan to West Pakistan. Most of the points revolved around safe guarding East Pakistan’s share of export revenues. It was also clear that a maximalist position had been adopted by the Awami League, which stemmed from absolute confidence that it had the support of the masses and could carry the programme through without any hitch. Relenting on the extreme position was foreseen only if the showing at elections was not as expected, and some compromises had to be made.

Mired in multiple problems and responsibilities, President Yahya paid title heed to the consequences of the Six-Point Programme on Pakistan’s unity. On the face of it, the Legal Framework Order7 (LFO) that circumscribed the 1970 elections process accepted the Six-Point Programme as reasonable and legitimate. On the other hand, it was the LFO, which irked Mujib sorely, particularly a clause that vested powers of authentication of the future Constitution with the President. It implied that Mujib would not have a free hand to implement his Six-Point programme even if he obtained a majority in the National Assembly. Apparently, Yahya felt self-assured because he could exercise his powers to veto the Constitution Bill if the need arose. In any case, Yahya trusted his intelligence agencies’ prognosis of a split verdict, and thought that the stage of a veto may not be reached. In case of a split electoral verdict, Yahya was sure that the points of conflict in Awami League’s radical programme could be resolved through coercive diplomacy when the time came for transfer of power. If Yahya had foreseen that Awami League could sweep the elections, his plan of action for transfer of power would certainly have been less cavalier. Blaming the Six-Point Programme as subversive after having accepted it as a bonafide election manifesto just did not make sense. Disapproving a Constitution Bill passed by the elected representatives on grounds that its Six Points were violative of national integrity was a poor back-up plan, and an extremely provocative one at that. Mujib is claimed to have confided to his senior colleagues, “My aim is to establish BanglaDesh8 I shall tear LFO into pieces as soon as the elections are over. Who could challenge me once the elections are over.’·9

Elections and the Ensuing Impasse

Elections to the National Assembly were held on 7 December 1970 and to the Provincial Assemblies ten days later. Overall voter turnout was fairly high, with 58% of the registered voters casting their votes in the National Assembly elections. The turnout was considerably higher in the West Pakistani provinces 65%, compared to East Pakistan with 55%.

Of the 300 seats contested in the National Assembly, Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rahman’s Awami League won 160 (all in East Pakistan), while Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) won 81 (all in the West Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Sindh). The rest of the 59 seats were won by minor parties and independent candidates without any party affiliation. Clearly, Mujib had swept the elections, and was eager to take the chair of the Prime Minister.

Yahya and his coterie, as well as many West Pakistani politicians, were wary of a government led by the Awami League, whose radical programme was interpreted as thinly veiled separatism. There was also the anxiety about Awami League allying with the smaller parties and independents to get a two-thirds majority, and bulldozing its Six Point Programme in the National Assembly with full constitutional cover. Two days after the elections, Mujib unequivocally declared, “The election for the people of Bangladesh was above all a referendum on the vital issue of full regional autonomy on the basis of Six Points therefore a Constitution securing full regional autonomy on the basis of Six Points formula has to be framed and implemented in all respects.”10

It was feared that the Awami League could even take the extreme step of an outright declaration of independence in the National Assembly if it felt that the military was creating hurdles in its agenda. Misgivings also resurfaced regarding Mujib’s past involvement (1968) in the Agartala Conspiracy case in which he, along with 34 military officers, was accused of colluding with Indian agents in a scheme to divide Pakistan. A trial for sedition could, however, not go through due to large-scale protests and strikes in East Pakistan, and the charges were eventually dropped as a political expedient.

As if to fortify its position in the face of reservations in West Pakistan, the Awami League held a rally in Dacca on 3 January where all its recently elected members of the National and Provincial Assemblies took an oath of allegiance to the Six Points. The move clearly signalled that there was no possibility of bargaining, and the Six Points were there to stay, unaltered.

Faced with an utterly convoluted predicament, Yahya decided to visit Dacca on 12 January for parleys with Mujib and his team, “to come to a thorough understanding of the Six Points.” Vice Admiral S M Ahsan, the Governor of East Pakistan who was in attendance ruefully reminisced later that it was too late to attempt a ‘thorough understanding’ of the Awami League programme. The discussions, unsurprisingly, were frustrating for Yahya, as Mujib repeatedly insisted on each point by proclaiming that, ”There is nothing objectionable in it. What’s wrong with it? It is so simple.”11 Professor G W Chaudhry, the Minister of Communications who accompanied Yahya to Dacca thought that Yahya was bitter and frustrated by Mujib’s betrayal. “Mujib has let me down. Those who warned me against him were right. I was wrong in trusting this person,” said Yahya, according to Chaudhry.

A completely flustered Yahya sought counsel from Bhutto at the latter’s family residence in Larkana, to which he flew on 17 January. What transpired at Al Murtaza is not exactly known, but it appears that Bhutto was able to convince Yahya about the consequences of handing over power to Mujib, in view of the latter’s unrepresentative electoral standing in West Pakistan. Bhutto and Yahya also deliberated upon the seditious nature of Awami League’s manifesto, whose actualisation was now imminent. “We discussed with the President the implications of the Six Points and expressed our serious misgivings about them.”11 Whatever went on at Larkana during three days of parleys (interspersed with duck shoots), Yahya emerged satisfied after having enlisted his host’s support.

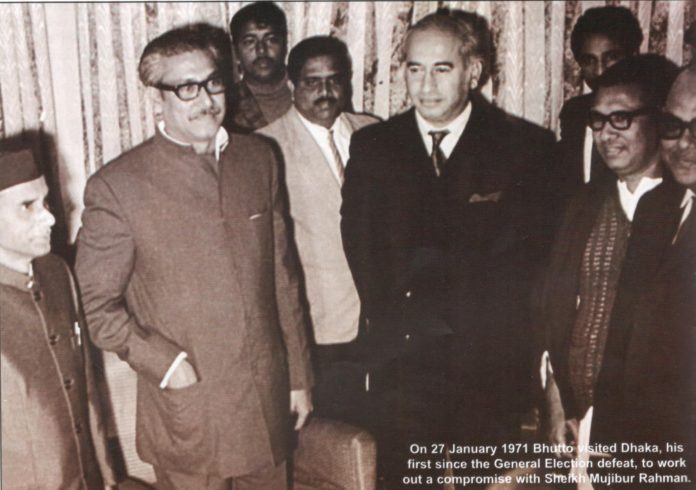

Backed by Yahya’s brief and confident of his own astuteness, Bhutto decided to visit Dacca on 27 January. Though piqued by the goings-on between Yahya and Bhutto in Larkana, Awami League was still amenable to the latter’s visit. It was interested in Bhutto’s cooperation only to the extent of rendering the President’s veto on the Constitution Bill ineffective. There was to be no compromise on the Six Points by Awami League. Bhutto, on the other hand, was seeking a power-sharing formula on the grounds that his Pakistan People’s Party had not received any mandate on the Six Point Programme, and public opinion was against it in West Pakistan. This stance was obviously unacceptable to Mujib who was not seeking any coalition partners. With the situation at a total impasse, Bhutto returned from Dacca in a recalcitrant mood.

Under the rapidly deteriorating political situation Yahya thought it wise not to delay the announcement of the National Assembly session any further. After all, the veto power vested in the President by the LFO was an adequate safeguard against the possibility of Awami League bulldozing the Six Points through the National Assembly. Yahya had another long discussion with Bhutto on 11 February, but without arriving at any agreement. He decided to go ahead with the logical next step following elections, and on 13 February, it was announced that the National Assembly would meet at Dacca on 3 March. Two days later, Bhutto declared at a press conference in Peshawar about his party’s inability to attend the inaugural session of the National Assembly, “in the absence of an understanding, compromise or adjustment of the Six Points.” He even threatened “a revolution from Khyber to Karachi if the People’s Party were left out.”13

With people in East Pakistan already seething with resentment at the delay in power transfer, and Bhutto out rightly threatening an uprising in West Pakistan if he did not have his way, matters had come to a head for Yahya. He once again wore his military hat, dismissed the civilian cabinet, and reverted to Martial Law in its classic form.

Vice Admiral S M Ahsan and Lt Gen Sahibzada Yaqub, the Martial Law Administrator in East Pakistan, were summoned by General Yahya to Rawalpindi for a conference on 22 February. Both were told that Mujib would be given one more opportunity to prove his good intentions. This implied a political dialogue with Mujib, failing which, military plans would be operationalised to regain full control in the disorder that was bound to ensue.

While Lt Gen Yaqub finalised the military plans for internal security, Vice Admiral Ahsan held a round of talks with Mujib. The only outcome of the talks was that Mujib agreed not to insist on application of the Six Points to Wes Pakistan, but there would be no change to their application to East Pakistan. Nonetheless, it seemed that the Awa mi League got the drift of military preparations, and was starting to show some flexibility. Lt Gen Yaqub had, in the meantime. sent a telegram to Yahya, urging him to visit Dacca immediately in the hope of averting a major crisis that he saw looming.

Disregarding Lt Gen Yaqoob’s telegram, Yahya announced on 28 February a sine die postponement of the National Assembly session which was originally planned for 2 March. This was done ‘to allow more time to the political parties to work out an agreement on the draw” Constitution outside the Assembly to the Awami League, this act was tantamount to repudiating the popular mandate. Yahya had overlooked the fact that Mujib had immense street power in East Pakistan; more ominously, he had full support of India which would not let go the distinct possibility of Pakistan’s break up. Regrettably, Yahya had played not India’s hands with his ill-considered announcement, and the die had been cast.

Postponement of the National Assembly session resulted in immediate protests, and the start of a civil disobedience movement in East Pakistan. Radio Pakistan Dacca was taken over by Awami League miscreants and calls for protests were broadcast, triggering a complete shutdown in major cities. Mujib sternly demanded an immediate transfer of power to the elected representatives of the people of Pakistan. Sensing violence, and belatedly heeding to some sane advice, a wavering Yahya made another announcement on 6 March for the inaugural session of the National Assembly to start on 25 March.

Bhutto, who had no chance of ‘arming even a coalition government at the Centre, fast-tracked his machinations in the wake of Yahya’s latest announcement. He cleverly floated the idea that, “If power is to be transferred to the people before a constitutional settlement, then it is only fair that in East Pakistan it should go to the Awami League, and in the West to the Pakistan People’s party, because while the former is have majority party in that wing, we have been returned by the people of this side.” The daily Azad of 15 arch 1971 gave a twist to Bhutto’s speech with a startling headline that screamed, ‘udhar tum, idhar hum’ you there, we here). Though the Nording of the headline has been incorrectly attributed to Bhutto ever since, a confederal structure, had, in effect, been proposed by him. Bhutto’s ambition and impatience came through clearly from his statement. His formula overlooked the fact that the Legal Framework Order had no stipulation for a political party having to win seats in other provinces, or both the wings, to be able to form a government at the Centre. Mujib’s disparaging of any such belated ploys was, thus, neither surprising, nor unfounded.

There were a few last-minute amendments to the Six Points suggested by the Awami League Executive Committee, which were conveyed to Lt Gen Yaqub. The amendments called for a token ratification of some of the contentious provincial subjects by the Central Government before implementation. These amendments were expected to be discussed with General Yahya, if he decided to visit Dacca, which unfortunately, he delayed until it was too late.

(to be Continued)

End Notes

1. resolved that it is the considered view of this session of the All-India Muslim League that no constitutional plan would be workable in this country or acceptable to the Muslims unless it is designed on the basic principle, viz that geographically contiguous units are demarcated into regions which would be so constituted , with such territorial adjustments as may be necessary, that the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in majority as in north-west ern and eastern zones of India, should be grouped to constitute independent states in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign.”

2. “Bangladesh and Pakistan, Milam, William B; Hurst & Co, London, 2009, page 18.

3. Ibid, page 21

4. Witness to Surrender, Salik, Siddiq; Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1977, page 16.

5. Khawaja Nazimuddin was the second Prime Minister of Pakistan; he remained in the chair for 18 months. He belonged to the family of the Nawabs of Dacca, whose ancestral links to Kashmiri merchant’s date back to the early 1ath century. Muhammad Ali Bogra, a Bengali of the Pakistan Muslim League, was the third Prime Minister of Pakistan; he remained in the chair for 28 months. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, a Bengali of the Awami League, was the fifth Prime Minister of Pakistan; he remained in the chair for just one year.

6. The four provinces, the federally administered tribal areas, and 10 of the 13 princely states of the western wing were merged into a single province of West Pakistan on 30 September 1955, although an official announcement had been made a year earlier. This arrangement, called the One Unit, lasted till it was rescinded by President Yahya Khan on 1 July 1970.

7. The Legal Framework Order was announced by President Yahya on 31 March 1970. It laid down the principles of the future constitution to guarantee the ‘inviolability of national integrity’ and the ‘Islamic character of the Republic’.

8. The name Bangladesh was originally written as two words, a convention that was discontinued after independence. The two-worded nomenclature is referred to as such because of mention in various books, before the name Bangladesh was adopted.

9. This statement is said to have been secretly recorded on tape by intelligence agents, and was played to President Yahya, as claimed in Last Days of United Pakistan, G W Chaudhry; Hurst and Company, London, page 98. The statement has also been quoted in Witness to Surrender by Siddiq Salik.

10. The Pakistan Observer, Dacca, 10 December 1970.

11. Quote attributed to Vice Admiral Ahsan, Governor of East Pakistan, by Siddiq Salik in Witness to Surrender, page 33.

12. he Great Tragedy, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, 1971, page 20.

13. The Dawn, Karachi, 16 February 1971.