First article in this series

Art imitating life or life imitating art? This is the question philosophers have posed for years. Whether one is a proponent of the Aristotelian Mimesis of art imitating life or a supporter of the Anti-Mimesis philosophy of life imitating art, one thing is certain inspiration can come from anywhere. Consider.

The Chilcot inquiry in the UK setup to assess the Iraqi weapons of mass destruction (WMD) claims, suggested that the 1996 film The Rock might have been the inspiration behind the insinuation that chemical agents could be carried in glass containers. Recall that in The Rock, green globules of a nerve agent are secured in glass containers and deployed in Alcatraz prison in San Francisco.

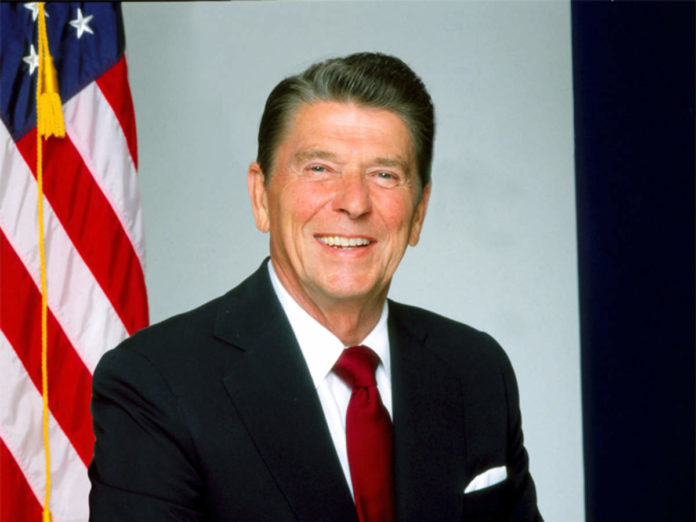

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan’s policy of Strategic Defence Initiative commonly known as Star Wars was most likely inspired by the film Torn Curtain in which Paul Newman plays an American rocket scientist tasked with retrieving Soviet plans for a missile defence system. But an even stronger indication of life imitating art comes from the fact that Reagan’s policy of nuclear deterrence was conclusively influenced by the film The Day After. The story goes that, in keeping with the film’s message, Reagan called for peace and nuclear disarmament knowing quite well that he would gain a propaganda victory over the Soviets by portraying them as the aggressors especially considering the fragile nature of the Soviet economy. This culminated in Reagan’s famous “tear down this wall” speech in Berlin. All this resulted in the complete dismantling of the Soviet Union.

Interestingly, President Kennedy was a personal acquaintance of Ian Fleming who thought up the James Bond character. Kennedy’s fascination with fictional espionage was said to be behind the Bays of Pigs debacle in Cuba. So much so that it is rumoured that afterwards he reflected “why couldn’t this have happened to James Bond”! Kennedy’s rose-tinted view of a policy of state sponsored espionage didn’t end there. He asked CIA officer Edward Lansdale to setup Operation Mongoose with the aim of toppling Fidel Castro. In personal circles, Kennedy used to refer to Lansdale as “our James Bond”. That is why Operation Mongoose had hair-brained schemes from contaminating Castro’s underwear to making his beard fall out. To no avail, as history shows.

In recent times, the US drama Madam Secretary has also dealt with the fictional universe of diplomacy and international relations. Though, based purely on conjecture and undoubtedly a one-sided interpretation of world events which this author doesn’t subscribe to. In one particular plot line, a Pakistani aircraft accidentally crashes on the Indian side of the border across Lahore. It’s cargo? A nuclear warhead that was being transported within Pakistan. The device becomes a bone of contention between India and Pakistan and the United States tries to mediate between the two nations. Pakistan’s just claim is that because it is a Pakistani plane, it should be allowed to enter Indian territory and run a salvage operation to reclaim the warhead. The Indians think that they can tackle this issue as the plane crashed in the Indian side of Punjab. The US Secretary of State runs between the Pakistani Prime Minister and the Indian Premiere with demands and inducements in order to come to an agreement. Something that will allow both parties to use the graceful window of exit that diplomacy demands.

As the story unfolds Elizabeth McCord the US Secretary of State, ably played by Tea Leoni, tries to appeal to the human side of both Prime Ministers by asking for peaceful co-existence between the two neighbours. Of course, dangling some carrots along the way and arm twisting to some extent is always par for the course. In the meanwhile, there are demonstrations in the streets of Islamabad. Wisely, the Pakistani Premiere lets equality prevail and allows the demonstrators to make their case. Although there is an amicable settlement in the end but not before a lot of diplomatic hurdles must be crossed by both parties.

Quite a roller coaster, isn’t it? Of course, it goes without saying that the above narrative comes from the imagination of the writers of the drama and won’t come to pass because sovereign countries such as Pakistan are capable of managing, maintaining and defending their own armament and territorial integrity come what may. Nonetheless the above scenario is intriguing! Not only because of its insight into diplomatic wrangling but also because it show-cases the policy options that might be a good fit to any end.

Therefore, the ultimate question is this, is it possible to find policy options in well written dramas such as Madam Secretary and other fictional sagas? The answer, quite so based on the above narrative.

Baseline opinion pieces in this series have defined policy as guidance that is directive or instructive; i.e. it is clear in stating what is to be accomplished. It is a galvanizing vision that describes the end goal and is selected out of a choice of possible directions. Recently, this author suggested that for the Imran Khan government, rooting out corruption is a good strategy but ultimately that strategy should be underpinning an overarching governmental policy. And in one word, that policy should be equality! Furthermore, in order to ensure peaceful co-habitation between Pakistan and India, a foreign policy of inclusionism was also much debated in one of the preceding op-eds quite recently.

Notice the resemblance of the policy options with the aforementioned fictional saga? It seems that even for diplomatic upheavals, art can imitate life and provide and corroborate policy formulations.

In the last ten odd years, there have been numerous films and television series that intermingle fact with fiction but still churn out credible policy options. From West Wing to Homeland and from 24 to Designated Survivor the list is plentiful.

As stated initially, inspiration comes in many forms. It doesn’t matter whether it is art imitating life or life imitating art. Our leaders and diplomats will do well to get on that bandwagon and be truly inspired whatever the form and do their jobs. Or else they will go the way of Andrew Shepherd another fictional US President as he laments “I was so busy keeping my job, I forgot to do my job”!

Second article in this series

BREXIT – nationalism, internationalism or patriotism?

Sunday, 11th of November 2018 was a historic day. It was the centenary of the end of the First World War and was marked with great respect in many countries across the globe. During one of these ceremonies in Paris, a dozen or so world leaders congregated and weighed in on this momentous occasion. One leader rekindled the spirit of camaraderie of 100 years ago that was essential in bringing WW I to an end. He suggested, “Let’s remember: let’s take away none of the purity, the idealism, the higher principles that existed in the patriotism of our elders. In those dark hours promoting universal values, was the exact opposite of the egotism of a people who look after only their interests”. This was because “patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism: nationalism is a betrayal of it. In saying ‘our interests first and who cares about the rest!’ you wipe out what’s most valuable about a nation, what brings it alive, what leads it to greatness and what is most important: its moral values”. The reader could be excused in thinking that this rhetoric may have come from a liberal and left of Centre prime minister or president. But it doesn’t! These are the words of the French President Emmanuel Macron! The leader of the conclusively nationalist French people. Essentially, he denounced those who arouse nationalist sentiment for personal gain and to disadvantage others, deeming it a ‘betrayal of patriotism’.

It says a lot, doesn’t it? Mostly because it takes great courage for a French president to stand up and effectively repurpose the centuries old call to nationalism into a demand for redefined patriotism. It must be the need of the hour!

Nevertheless, three questions arise from a policy perspective. One, what is the difference between nationalism and patriotism? Two, where does patriotism lie in the spectrum of nationalism and internationalism? Three, and most importantly, does this discussion provide any insight into the polarising discourse about BREXIT in the UK? At the very least, yes to the last question. Consider.

On one hand, there is nationalism. Although patriotism is used to define nationalism but in the ensuing debate since Macron made these comments, that can no longer be true. This new paradigm must have better demarcations of the three policy options. Nationalism is based, apparently, on the premise that the individual’s loyalty and devotion to the nation-state surpasses other individual or group interests. But in doing so it also confirms the notion of ‘our interests first and who cares about the rest!’ ably put by Macron. This is an isolationist ideology which is dangerous and frankly unrealistic for a globalised world. Any conservative base in any country would easily identify with this idea of nationalism.

On the other hand, internationalism is a policy which generally transcends nationalism and advocates a greater political or economic cooperation among nations and people. The European Union (EU) project is one such example. Voter base given to liberal tendencies would be sure proponents of such an interpretation of internationalism. However, both nationalism and internationalism are a difficult sell for any government. Supporting one of the two definitely alienates the half that aligns to the other policy. That is why liberal governments generally feel a backlash from conservative commentators and leaders. While conservative administrations experience the same treatment from those of a liberal disposition. Can these two ideas be reconciled? Perhaps yes, it seems that Macron’s newly defined notion of patriotism might hold a clue.

This new model of patriotism is based on invoking the memories of the allied forces working together for the greater good in a ‘win-win’ scenario for all involved. Although this doesn’t jettison the idea of being loyal to one’s own nation but also, at the same time, advertises the advancement of common interests that are complimentary to national interests. In-fact, reusing the French president’s language, international patriotism could mean ‘our interests first along with caring for the rest’! It won’t be easy as the margins of nationalism and internationalism have been entrenched for centuries. Nevertheless, international patriotism can be seen in a new light and can become the middle ground between the two extremes.

Can this help the BREXIT debate and make any deal between the UK and the EU palpable on both sides of the leave and remain divide? Yes!

The leave camp has mostly canvassed on a message of closing down UK borders and embarking upon independent policy formulations away from the ‘over-bureaucratic’ politicians from the European Parliament. Therefore, the ‘leavers’ have taken a very nationalistic approach to BREXIT though they try to balance it with a hint of globalism by suggesting that Britain will be free to trade with the rest of the world once out of the EU.

The remain voters believe that the regional and international engagement is key and thus the UK must be part of something bigger, like the EU, in order to prosper further and secure the people and the state in a globalised environment. This argument is mostly an internationalist position.

The partisan debate since the BREXIT vote in 2017 suggests that the only way of reconciling these disparate views would be to re-contextualise the discourse around BREXIT within the newly suggested idea of international patriotism. That might appease both the leave and remain camps as staunch supporters would be able to find at-least the majority of their ideological narrative intact.

Emmanuel Macron prides himself on being a modernising force and he has struck a chord with his speech on Armistice Day. It would be unfortunate for the people of this planet that his suggestion to capture the middle ground through reinterpreting patriotism is not taken to its logical conclusion and adopted and defended world-wide. Because, “it’s co-existence or no existence!” as per Bertrand Russell.

Third article in this series

There is no such thing as a free lunch in policy formulation!

In the economic world, the phrase ‘there is no such thing as a free lunch’ has gained much currency since the 19th century. It is rumoured that this comes from the American businesses of the time which actually did use to serve free lunches in bars and drink houses with the expectation that consumers will come for the free lunches but end up paying for them in drinks they would be obliged to buy.

In the annals of policy making, the same phenomenon is at play and could be stated as paying with consequences, intended and unintended, for advancing any particular course. That is, in the end, all policy options have a price. And the advent of globalisation makes it an even more ardent certainty. Consider.

Thomas Friedman defines globalisation as the integration of markets, finance, technology, and telecommunications in a way that is enabling each one of us to reach around the world farther, faster, deeper, and cheaper than ever before. And at the same time, globalization is enabling the world to reach each of us farther, faster, deeper, and cheaper than ever before. Hence, the democratisation of information, technology and finance ensures that no event or underpinning policy is localised and that these will always have global ramifications.

The Syrian refugee crisis is how the world paid for its policy miscalculations in Syria! It all started with the Arab Spring of 2010 and the policy of armed repression of the movement within the country. This continued with a violent crackdown on dissidents which strengthened the hands of non-state actors. Then, US and Russia embarked upon a proxy war in Syria by backing opposing parties. The former strengthening co-operative rebel groups by providing them with training and small arms. The latter racing to the defence of Bashir Al Assad while ignoring the ground realities. This interventionist action, seemingly a boxing match between the heavy weights, exacerbated the problem further rather than curtailing it.

The idea behind the intervention was to contain the conflict before it spiralled out of control and affected the rest of the world. Did it? It certainly did not!

According to the UNHCR Over 5.6 million people have fled Syria since 2011, seeking safety in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and beyond. A total of 13.1 million people are in need of aid within Syria along with 6.6 million internally displaced persons. Being the Northern neighbour to Syria, Turkey is housing the biggest number of Syrian refugees about 3.3 million. But not before the world had to pony up the dough and that too in billions to get Turkey to agree to this deal. And what is the main aim of this agreement? That Turkey will restrict or reduce the north ward migration of these Syrian refugees. Again, the world seems to think that this will be a localised or regionalised event and again, it will be wrong!

A similar story played out in the late 70s and early 80s during the ‘Afghan Jihad’ a new great game played in Afghanistan at the behest of the US and the Soviet Union. Then too the idea was to contain the conflict, and the related fallout, using this flawed policy of unrealistic intervention. When Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s National Security Adviser, had the Mujahedeen created by Pakistan as proxies he wrote to the President, “we now have the opportunity of giving to the USSR its Vietnam War”. While he achieved some intended consequences, the unintended consequences were the ones for which the world paid a heavy price. The Muslim world in general, and Pakistan in particular, ended up facing the biggest brunt of this onslaught in the form of millions of Afghan refugees and the returning ‘America backed’ fighters who consequently became a nuisance as converted non-state actors.

Furthermore, since the late 80s and early 90s, the scourge of terrorism has extended outwards from its original conflict zone and into the heartlands of US and especially that of Europe. The world thought that this will never reach its doorstep and it will get away scot free. How wrong it was!

This has also been helped by the democratisations of information, technology and finance as described by Thomas Friedman. All the more reason that payback is quick, efficient and unfortunately in most cases deadly. According to Interpol, in 2017, 62 people were killed in 33 religiously inspired terrorist attacks in the EU, compared to 135 deaths in 13 attacks in 2016.In 2015, the number of deaths caused by this kind of attack reached a peak of 150, sharply up from four in 2014.

Moreover, nowhere the notion of ‘no free lunch’ finds more acceptance than in the corridors of international diplomacy. Since coming to power, Donald Trump’s response to the escalating tension in South China Sea has been the ‘quid pro quo’ policy. The Trump administration still believes, naively probably, that China can be persuaded to agree to a greater political and security deal in return for helping the US keep the Korean Peninsula safe. Along with the Americans promising they will do their best to wipe out trade deficit with China. Though, this might have been jeopardised by the newly found pessimism in the ‘tariff wars’ between the two countries. To Japan, the US is continuing to promise security guarantees, enhancing the existing US-Japan defence agreement but want, in exchange, more opportunities for American trade and investment. The global stage is full of such examples which confirms that there is no free lunch indeed.

Therefore, from the refugee crisis in Syria to the human and security costs of the Afghan war to the inducements regime in global negotiations, one message stands out: every action has a price and every policy has consequences. Hence, the leaders of today and tomorrow will have to bear that cross because whatever course they pick, there is no such thing as a free lunch!

Fourth article in this series

Is social media an effective tool for policy discourse?

Social media is officially part of the business, political and governmental environment. It is a very strong consequence of the three democratisations of information, technology and finance as described by Thomas Friedman. Thus, information is now available to a majority of the planet “farther, faster, deeper, and cheaper than ever before”. Social media is the biggest tool available that implements this new paradigm. But the question is this, does it affect the art of policy formulation and ensuing strategy execution? Yes, it does! But in a variety of ways and not always with a positive impact. Consider.

Contrary to popular belief, social media has been around in a number of forms and with a subsequent influence on different social spheres to match. Just before the French Revolution, the French finance minister strongly suggested the importance of ‘investor confidence’ to maintain social and financial cohesion. In the early part of the 19th century, the print media started to use ‘straw polls’ with the first one rumoured to appear in 1824. In the US, private organisations such as American Institute of Public Opinions pre-cursor to the Gallup corporation were focused on querying the mood of the electorate on a variety of topics. Since then not only gathering societal information has been pertinent but also influencing people’s mood has been a crucial lynchpin of the social media saga.

A good, modern day example of the optimal and appropriate use of social media would be President Obama’s re-election effort in 2012. The campaign team included a Chief Technology Officer, Chief Innovation Officer and even a Director of Analytics. They used voter data to identify voting patterns and also delivered localised and GPS dependent content to their support base. The clever aspect to all this was that even policy statements were disseminated using a myriad of social interfaces. This approach did work as Obama won a second presidential term.

From policy announcements to feuding with governmental institutions to firing people. It is rumoured that Rex Tillerson, former Secretary of State, got to know of his firing from Twitter! So did Reince Preibus, the previous Chief of Staff. White House council Don McGahn also found out that he was leaving from one of Trump’s tweets!

Donald Trump has also used Twitter for major policy statements. In July 2017, He announced his decision to ban transgender troops. James Mattis, the Secretary of Defence at the time, got to know about this one day earlier while he was on vacation. Suffice to say, the White House and the Pentagon were in damage limitation mode after this news broke on Twitter! The Trump Kim Jong-un meeting also got an honourable mention in quite a few of Trump tweets. His first tweet of 2018 was to flay Pakistan, wrongly so, for not doing much in the war on terror when Pakistan is the only country in the front line of this war and has lost over 70,000 lives!

Moreover, the armed forces of different countries use diverse social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to make major announcements, respond to geo-political scenarios and lend clarifications and provide further information on a variety of topics. In the US, the Pentagon does it with aplomb while in Pakistan, the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) uses social media with great affect.

The conclusion must be that social media is a very effective tool in getting policy arguments across to a wider audience “farther, faster, deeper, and cheaper than ever before”. But, for this to be effective and beneficial, some principles must be kept in mind. Or else it could backfire tremendously!

First, knowing one’s audience is key. This needs at-least some understanding of the people with whom one can engage on different platforms. There are a myriad number of ways to obtain social data to aid with this understanding. Second, policy announcements must be made when the top tier leadership whether it is a government, corporation or organisation is on the same page. A policy shift should never come as a surprise to anyone in the inner sanctum! Third, certain norms of diplomacy must be kept in mind when making major announcements. Premium among them is to not box an ally, or even a foe, in a corner from which there is no retreat. This is counterproductive for both parties. Fourth, keep policy and strategy announcements succinct and allow the process outside of social media to expand upon the details. The character limit on platforms such as Twitter should help this to a great extent. Fifth, prepare for backlash. Remember that policy statements will not be received in kind from both sides of the aisle. This is the time to avoid knee-jerk reactions and remain calmly and concisely on topic. Sixth and most importantly while social media is a good tool to reflect succinctly policy discussions and decisions but there is a plethora of leg-work and activity at the strategic, operational and tactical levels that doesn’t need to become part of this piece and must exist outside of such platforms.

There is no escaping social media. It is everywhere and that is the key policy and strategy information can be disseminated efficiently across this medium. If that is not done, then other non-representative actors can hog the limelight for their own ends. Thus, it becomes a necessity to use social media but while keeping the aforementioned values in mind. Ultimately, it is a fine balancing-act between populism and principle. Politicians might be occasionally guided by populism, but true leaders should always be led by principles!