Akbar Khan (1912-1994) was a Pathan from Charsadda area of Khyber-Pukhtunkhwa. He was from the pareech khel clan of Muhammad zai tribe that inhabits the village of Utmanzai. Akbar was from the last batch of Indian officers commissioned from Royal Military College Sandhurst in February 1934. Lieutenant General B.M. Kaul “Bijji” was his course mate at Sandhurst and they became friends during their service. Officers commissioned from Sandhurst were called King Commissioned Indian Officers (KCIOs). Akbar joined 6/13 Frontier Force Rifles (FFRif.). This battalion is now One Frontier Force (FF) Regiment of Pakistan army. He fought Second World War with 14/13 FFRif. (now15 FF). This was a new war time battalion raised in April 1941, at Jhansi. In new war time raised battalions, officers and men were posted from different battalions, usually from the same regimental group. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Felix-Williams, DSO, MC of 1/13 FFRis. was the first Commanding Officer (CO). There were fourteen officers in the battalion and Akbar at the rank of Major was the senior most of the four Indian officers of the battalion. Lieutenants H. H. Khan, Fazl-e-Wahid Khan and A.K. Akram were other Indian officers (Wahid won MC). Battalion was part of 100th Brigade (other battalions of the brigade included 2 Borderers and 4/10 Gurkha Rifles) of 20th Division commanded by Major General Douglas Gracey.

14/13 FFRif. was one of the few battalions well trained in jungle warfare and performed admirably. Battalion received three DSOs and 14 MCs. This included two MCs to Viceroy Commissioned Officers (VCOs); Subedar Bhagat Singh and Subedar Habib Khan. Battalion was patrolling about 1000 square mile area and many detachments were not in contact with battalion HQs. Akbar was commanding two companies (B & C) during Irrawaddy crossing and was quite independent in his command due to poor communications with battalion HQs. Battalion’s defenses fought against the onslaught of Japanese and suffered forty-six killed and more than 100 wounded. Akbar withdrew his two companies into the lines of 9/14 Punjab Regiment. Akbar fought very well and won his Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in June 1945. (Daniel Marston’s excellent work Phoenix from Ashes is the most authoritative work of documenting performance of Indian officers in Second World War as well as British-Indian relations.)

At the time of partition in 1947, Akbar was the only serving Pakistani officer with DSO. Former Air Chief Air Marshal Asghar Khan narrates an incident that happened on Pakistan’s Independence Day on August 14, 1947. Country’s founder and Governor General Muhammad Ali Jinnah gave a reception on that day. A group of about dozen officers of armed forces were also invited. Akbar then Lieutenant Colonel suggested to Asghar that they should talk to Jinnah. Akbar told Jinnah that officers have hoped that in new country “our genius will be allowed to flower” and that he was disappointed that “higher posts in the armed forces had been given to British officers who still controlled our destiny”. Jinnah pointing his finger reprimanded Akbar stating that “Never forget that you are the servants of the state. You do not make policy. It is we, the people’s representatives, who decide how the country is to be run. Your job is only to obey the decisions of your civilian masters”. Akbar’s views were well known on this subject and even before partition he had testified before Armed Forces Nationalization Committee and advocated immediate nationalization of armed forces. However, Akbar’s admirers and detractors will interpret these events differently.

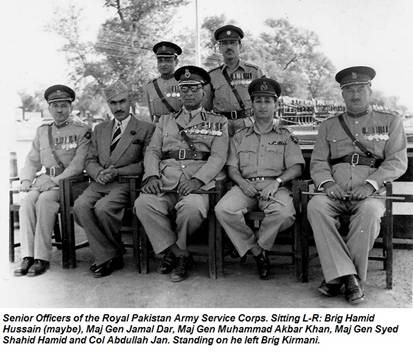

In September 1947, Colonel Akbar was appointed first deputy director of Weapons & Equipment (W&E) directorate. He got involved with Kashmir operations when he was appointed military advisor to Prime Minister. He used code name Tariq during Kashmir operations. He was given the command of 101 Brigade based in Kohat. He moved his brigade from Kohat to Uri sector in Kashmir. In addition to his own brigade, Akbar was also coordinating activities of the tribesmen operating in Kashmir. He commanded 101 Brigade from April 1948 to January 1950. After Kashmir operations, 101 Brigade was moved to Sialkot. In 1950, he attended Joint Services Staff College course in London. He came under suspicion of British authorities when he met some communists in London. This information was passed on to Pakistani C-in-C General Gracey who already knew about Akbar and some other officers and called them “Young Turk Party”. In December 1950, he was promoted Major General and appointed CGS.

Several officers involved in Kashmir operations were upset at the ceasefire and this resentment evolved into talk about overthrowing the government. Akbar took advantage of these sentiments and became the leader of the conspiracy. The roots of this problem lie in the fact that during Kashmir operations, new political leadership used junior officers out of normal chain of command resulting in breakdown of discipline. Senior British officers warned Pakistani civilians about this mistake. In March 1951, he was arrested along with several other officers. A special tribunal convicted and sentenced him to five years in prison. He was released in 1955. He joined Pakistan People’s Party and served as Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s national security advisor in 1972.

Akbar was married to Nasim Akbar. Nasim was a social, educated lady from a very affluent family of Lahore. She had leftist ideas and it was alleged that Akbar was under the influence of his wife. Nasim was an ambitious woman and allegedly aspired to become the first lady. Nasim was present in some of the meetings of the conspirators but she was not charged with any offence. In fact, many officers were upset when Akbar brought some civilians including his wife into the loop. The couple divorced in 1959.

Akbar has been a controversial figure in Pakistan army history. Some leftists believe that if Akbar had succeeded in 1951, Pakistan army would have been pushed into the “left lane”. Seven years later, General Ayub Khan’s coup decisively put army and the country in the “right lane”. Akbar was well respected by his juniors for his professionalism, gallant performance in war and ease of interaction with juniors. On the other hand, he had a mercurial temper and at times behaved in a bizarre way. Several incidents are narrated as evidence of this bizarre behavior but two examples will suffice. When he was major general, he used to keep a rope at his office table declaring to visitors that some people need to be hanged with this rope. In February 1972, when he was national security advisor of Prime Minister Bhutto, there was strike by policemen in Peshawar. Akbar phoned commandant of school of artillery at nearby Nowshera asking him to send two 25 pounder artillery guns to sort out policemen. The order was cancelled by army headquarters. There was some violent streak in his personality and different interpretations have been offered. One suggests that in view of family trait of violence, he may have inherited some psychological illness that made him prone to bizarre behavior. Another theory points towards his clan. Pathans are generally viewed as having short tempers and even among Pathans, pareech khels are known for even shorter fuses.

The ironies of the times can be judged from the fact that before independence, Akbar portrayed himself as an ardent nationalist and had no love lost for the British. However, after independence, when he was given his dismissal order by Major General Mian Hayauddin “Ganga” (4/12 FFR), he wrote on the paper that he was a King’s commissioned officer and could not be dismissed even by Governor General. Long after independence, Akbar was now claiming to be the subject of the King/Queen rather than citizen of Pakistan.