“We know that it was not strategy nor tactics nor leadership that really gained us the victory, but the spirit of sacrifice”. General Sir William Birdwood’s address on unveiling of the Punjab Frontier Force (PIFFER) Memorial at Kohat October 23, 1924.

It is impossible to narrate the story of the Indian Army in the Great War on ethnic or religious lines as some modern observers are tempted to do. It is equally futile to attempt a “revisionist” narrative through the nationalist lens of modern India and Pakistan. What were then Indian soldiers of many different religious and ethnic backgrounds fought in the Great War under their regimental standards as imperial British subjects of the Indian Empire on a global battlefield.

In 1947, British India and its armed forces were divided between the two new nations of India and Pakistan. Punjab Province, which had provided the bulk of the old regular Indian Army, was carved up with a few strokes of the cartographer’s pen. Ambala and Jullundur divisions and Amritsar and Gurdaspur of the Lahore division became part of India. Punjabi Muslims, Muslim Rajput’s and Pathans of the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) became Pakistani citizens while Sikhs, Jats, Dogra and Rajput Hindus became Indian citizens. All of this cut across the traditional structures and allegiances of the old Indian Army, and the Great War experiences of men such as Subedar Major Parbhat Chand, a Hindu Dogra, who won a Military Cross fighting under the colours of the 59th Scinde Rifles, which would later become the 1st Frontier Force Regt. of the Pakistani Army, the many Punjabi Muslim sepoys who served under the colours of the 125th Napier’s Rifles and 101st Grenadiers which were allotted to India in 1947, and medical officers Capt. Indrajit Singh of the 57th Rifles and Major Atal of the 129th Baluchistan Infantry who died alongside their Punjabi Muslim and Pathan comrades. While these and other factors discourage any attempt to interpret the conflict in light of the later partition of the subcontinent, there is no reason why the war-time experience of what is now Pakistan, especially the Punjab, should not be studied in the same way that, for example, the impact of the war on the north of England and regiments raised there are examined for insights.

India raised a volunteer army of 1.4 million men in the First World War; by November 1918, the Indian Army had 413,000 soldiers on active duty. The Punjab sent 282,000 recruits to the army (156,000 Muslims, 63,000 Hindus and 62,000 Sikhs) during the course of the war. In October 1916, 10,000 drivers for transport units were recruited in Punjab in just 18 days. This disproportionate contribution of men reflected how the Punjab had long been the principal recruiting ground of the Indian Army; of the army’s total strength of 180,000 men on the eve of the conflict, more than 100,000 soldiers came from the province. Muslims formed 51% of the provincial population, Hindus 36% and Sikhs 12%. Punjabi soldiers were recruited from princely states as well British-administered districts in the Punjab. The NWFP, also within modern Pakistan, was also a major recruiting ground for the Indian Army before 1914.

Traditionally, the Indian Army only recruited from certain classes and districts of the Punjab and the NWFP because of the notion of “martial races” which claimed that the men of certain communities were natural soldiers for historical, ethnographic, social and other factors while other groups were unsuited to military life and war. Sikhs, Punjabi Muslims, Jats and Dogras from the Punjab and Pathans from the NWFP were considered among the finest of the martial races. Even within these races, however, the military deemed that only men from particular subgroups and regions made suitable recruits while their cousins or neighbours might be seen as lacking military qualities. Just a few districts of what is now Pakistan provided the lion’s share of recruits for the army. In Punjab, Rawalpindi, Jhelum, Attock, Shahpur and Gujrat districts of the Rawalpindi division provided the most recruits while Mianwali district sent very few men to the army. On the eve of war, over 28,000 men from the Rawalpindi division were serving in the army. In contrast, Multan division, comprising Montgomery, Lyallpur, Jhang, Multan, Muzaffargarh and Der Ghazi Khan, had less than 500 men in the army.

There was great variation even within the districts and ethnic groups from which the army recruited. In Gujrat distrist, Kharian Tahsil (subdivision) produced large numbers of recruits during the war while Phalia Tahsil in the same district sent very few. In Shahpur district, Khushab Tahsil sent large numbers of men while Bhalwal Tahsil did poorly. In Mianwali district, a single group of Bhangi Khels provided almost all of the recruits while very few Niazis in the same district opted for a military career. The Ghakkars of Jhelum and the Sattis of Rawalpindi sent 90% of their military age men to the army while just 20% of military age men of the Gujars of Rawalpindi and the Joyas of Shahpur served during the war. All of these facts are worthy of further, detailed historical study.

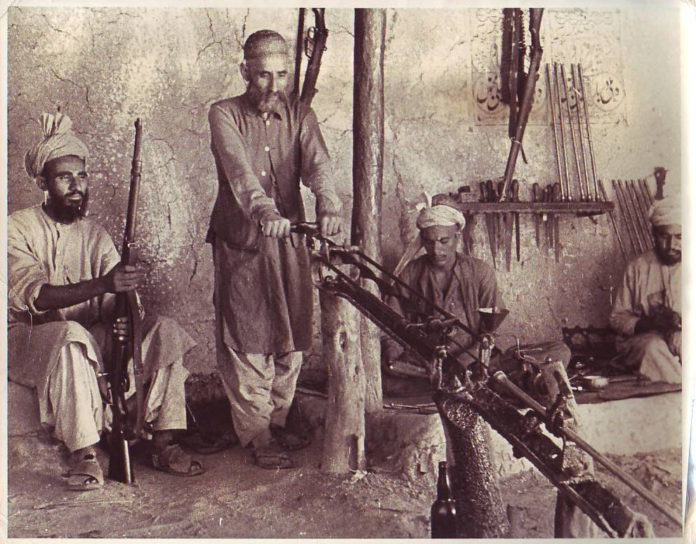

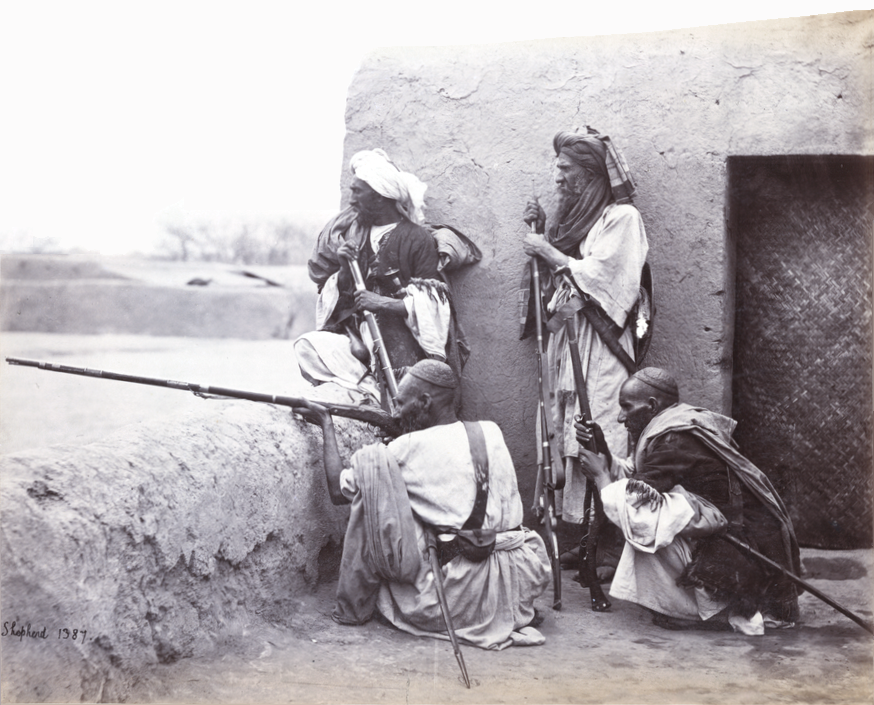

The Pathans were considered an outstanding “martial race” and highly prized as recruits while the Pathans considered soldiering as an honorable profession. This combined ‘push-and-pull’ resulted in over recruitment of Pathans. The NWFP had five British administered districts, but just three of them, Peshawar, Hazara and Kohat, provided most of the region’s recruits. Tribesmen living in the trans-frontier area, who were classified as British protected subjects and administered indirectly by a small cadre of British officers of the Indian Political Service (IPS), also served in the Indian Army. These independent tribes were known more for their frequent clashes with the army, and the countless military expeditions sent against them. It was far less well known that large numbers of tribesmen flocked to the regimental colors of the same army or proudly served in paramilitary forces such as the Frontier Constabulary and Frontier Corps.

In proportion to its population, the NWFP sent more military-aged men to the army during the Great War than any other province of India. It literally mobilized the flower of its youth with 85,000 men out of a population of 177,000 men of military age serving in the army and paramilitary forces. More than 96% of these men served as combatants. Some groups in the NWFP made contributions that were striking even by the high standards of the province. The sanctioned strength of the Khattak Tribe in the army was 23 companies of 114 men each for a total of 2,622, however, 3,400 Khattaks were in the ranks by 1918.

Many of the Indian troops sent to the European, Middle Eastern and East African theaters were from the Punjab and NWFP. Many illustrious regiments hailed from these regions and added to their reputations in the global conflict. The 129th Duke of Connaught’s Own (DCO) Baluchistan Infantry (now 11 Baloch Regiment in the Pakistani Army) was an all Muslim battalion on the eve of the war consisting of six Pathan and two Punjabi Muslim companies. The six Pathan companies were all trans-frontier Pathans – three Mahsud, two Adam Khel Jowaki Afridi’s and one Mohmand. It fought in France and later in East Africa, suffered heavy casualties and received repeated replenishments from sister battalions. Its depleted ranks were replenished with Mahsud and Wazir Pathans of the 124th Duchess of Connaught’s Own Baluchistan Infantry (now 6 Baloch Regiment) and Orakazai Pathans and Baluchis of the 127th Baluchistan Infantry (now 10 Baloch Regiment). More than 4,000 men served under the 129th’s colours and it suffered more than 3,000 casualties. The 40th Pathans (now 16 Punjab Regiment) was originally an all Pathan regiment. In 1900, its class composition was changed to four companies of Pathans (two Orakzai, one Afridi and one Yusufzai), two of Punjabi Muslims and two of Dogras. The battalion was decimated in France losing almost all of its British officers. It later fought in the East African theatre.

Indian Expeditionary Force – D which served in Mesopotamia was the largest contingent of Indian troops sent overseas with 400,000 combat and non-combat troops. Considerable numbers of soldiers from the Punjab fought in this theatre. The 20th Punjabis (now 6 Punjab Regiment), 22nd Punjabis (now 7 Punjab Regiment), 24th Punjabis (now 8 Punjab Regiment), 25th Punjabis (now 9 Punjab Regiment), 26th Punjabis (now 10 Punjab Regiment), 31st Punjabis (now 14 Punjab Regiment), 62nd Punjabis (now 1 Punjab Regiment), 66th Punjabis (now 2 Punjab Regiment), 76th Punjabis (now 3 Punjab Regiment), 82nd Punjabis (now 4 Punjab Regiment), 84th Punjabis, 89th Punjabis (now 1 Baloch Regiment), 90th Punjabis (now 2 Baloch Regiment), 52nd Sikh Infantry (now 4 Frontier Force Regiment) fought in the Mesopotamian theatre. The 21st Cavalry (now 11 PAVO Cavalry), 22nd Cavalry (now 12 Cavalry), 13th Lancers (now 6th Lancers) and the Guides Cavalry also fought in the Mesopotamian theatre. The Indian army suffered the largest number of casualties in this theatre; 11,000 men were killed in action, 4,000 died of wounds, more than 12,000 died of sickness, 13,000 were missing in action or Prisoners of War (POW), and 50,000 were wounded.

Indian Expeditionary Force – E fought in Egypt and Palestine. The 20th Punjabis (now 6 Punjab Regiment), 27th Punjabis (now 11 Punjab Regiment), 28th Punjabis (now 12 Punjab Regiment), 91st Punjabis (now 3 Baloch Regiment), 92nd Punjabis (now 4 Baloch Regiment), 51st Sikh Infantry (now 3 Frontier Force Regiment), 53rd Sikh Infantry (now 5 Frontier Force Regiment), 56th Rifles (now 8 Frontier Force Regiment) and 59th Scinde Rifles (now 1 Frontier Force Regiment) were part of this force.

Before the war, recruiting was done by “direct enlistment” whereby a soldier brought a relative directly to the regiment or by “class recruitment” in which recruiting officers enlisted only men from certain classes. Traditional recruiting continued during the first two years of the war, but it could not cope with the rapid expansion needed to meet war-time demands. In 1917, a new territorial system was introduced, and recruiting officers were instructed to recruit men from all classes in their administrative districts and divisions.

The Indian Army, like all forces in the conflict, suffered terrible losses. More than 37,000 Indian soldiers were killed in action of which 12,900 came from the Punjab along with more than 20,000 wounded from the province. The Punjab Frontier Force, recruited from the Punjab and the NWFP, suffered casualties of 171 British offices, 122 Indian officers and 3,425 men. Many families from the Punjab and families sent several members to serve and fight around the world. Sharaf Khan of Jehlum sent six sons, one grandson and three nephews to the war, and when Fateh Din of Rawalpindi lost two sons in the war he enlisted his remaining son. A Hindu widow of Rawalpindi, Lal Devi, enlisted six sons. Some communities made similarly striking sacrifices: Narra; a small village in Attock inhabited by Pathans had 843 men serving in the army while Dhulmial in Jhelum with a total male population of 1,200 sent 480 men to the army.

Pathan enlistment presented the Indian Army with certain challenges during the course of the war. Recruiting of trans-frontier Pathan tribesmen was halted in 1915 following the desertion of some Afridi’s on the Western Front and the reluctance of some Pathans to fight the Turks as fellow Moslems. In 1914, there were 5,437 trans-frontier Pathans in the army, almost all in combat formations. A further 1,200 Afridi’s and 375 Orakzais enlisted before trans-frontier Pathan recruitment was stopped. Another 1,600 trans-frontier men were enlisted in labor units. In February 1916, the army’s Adjutant General issued an order that trans-frontier Pathan soldiers and new recruits could take voluntary discharge; 65 of 208 trans-frontier Pathans serving in the Peshawar Division choose to leave. Nonetheless, when the war ended, there were still 3,090 trans-frontier Pathans proudly serving in the Indian Army.

The most notorious case of desertion involving a Pathan soldier was that of Jamadar Mir Dast Afridi of the 58th Vaughan’s Rifles, who crossed over to the Germans in France. Disaffection sometimes troubled entire units. The 130th King George’s Own Baluchistan infantry (now 12 Baloch Regiment) was in Calcutta preparing to be deployed overseas. A Mahsud sepoy shot the battalion’s second-in-command, Major Norman Anderson, who later died of his wounds. The battalion was sent to Burma where some of the men of the Pathan companies mutinied. Subsequently, 200 soldiers were court martialed and two executed. The battalion was rebuilt with the remaining sepoys and two companies of the 46th Punjabis, and later fought in East Africa. There was also trouble in the 15th Lancers in Mesopotamia. Two Multani Pathan squadrons refused to fight the Turks close to holy Muslim sites while insisting that they were willing to fight in any other theatre. The unit had served in France without any problem. Trouble was not confined to Pathan units. Four Musalman Rajput companies of the 5th Light Infantry mutinied in Singapore. The rising was suppressed and 37 NCOs and men executed after summary trials.

Several factors accounted for the wavering of a few trans-frontier Pathan soldiers. Religion was the main factor when Ottoman Turkey entered the war on the side of the Central Powers. Despair, war fatigue and sheer instinct for survival in such a great conflict was common in all the armies involved. Trans-frontier Pathans had an unusual advantage, however, as their homes were outside direct British administrative control. If a trans-frontier Pathan could cross over to the Germans in France, there was a chance he could get back to his home via Afghanistan and live unmolested. This option was not available to soldiers living within British controlled areas; even if a deserter managed to come back alive, the justice system would apprehend him and exert punishment for desertion.

Pathan tribal dynamics were an additional complication. Units traditionally were based on a tribe and clan basis, and if a unit composed of a particular tribe or clan suffered large-scale casualties it could significantly change the balance of power back home where tribal feuds were endemic. The Malik Din Khel clan of the Afridi’s joined the army while the Zakkha Khels were not keen on military service. Active service in the Indian Army in the decades before 1914 consisted mainly of frontier campaigns that were not particularly bloody in terms of casualties. In the industrial-scale slaughter on the killing fields of France or Mesopotemia, it was possible for an entire Malik Din Khel company to be wiped out in a matter of hours or days. This could have a significant impact on the local power balance on their home turf because it would mean the Malik Din Khels could not muster enough fighting men against rival clans.

Despite these problems, trans-frontier Pathans fought bravely in all theatres. Afridi’s were the first Indian troops to enter the trenches in France and draw first blood. Some of the most daredevil attacks on the Western Front were performed by trans-frontier Pathans. On one occasion after many unsuccessful frontal attacks on some German trenches, a sapper officer, Capt. Acworth, and eight Afridi volunteers mounted a flanking attack, clearing the way for a successful assault. Four of the Afridi’s received the Indian Order of Merit (IOM) and four received the Indian Distinguished Service Medal (IDSM).

Trans-frontier Pathans, especially Afridi’s, won many gallantry awards. The sole Victoria Cross winner from the NWFP was a Malikdin Khel Afridi, Subedar Mir Dast of 55th Coke’s Rifles attached to 57th Wilde’s Rifles. Out of four Military Crosses won by men from the NWFP province, three were awarded to Afridis: Subedar Major Arsala Khan Malikdin Khel Afridi of 57th Wilde’s Rifles; Subedar Gul Akbar Malikdin Khel Afridi of 24th Punjabis; and Jamadar Hawindah Kambar Khel Afridi of 58th Vaughan’s Rifles. The sole NWFP winner of the Indian Order of Merit (IOM) 1st Class was a Mahsud, Jamadar Ayub Khan of the 124th Baluchistan Infantry. Out of 61 IOM 2nd Class winners from the province, 23 were won by trans-frontier Pathans. The most decorated NWFP native officer, Subedar Major Arsala Khan of 57th Wilde’s Rifles, (now 9 Frontier Force Regiment of the Pakistan Army) was a Malikdin Khel Afridi from the independent tribal area of Tirah. He won the IOM in the 1908 Mohmand expedition, an IOM and MC in France and an OBI in East Africa.

Men from areas now comprising Pakistan, especially Punjabis and Pathans, fought all over the globe. In doing so many were part of a military tradition that preceded and continued after the 1914-18 conflict. One case of a century of uninterrupted service over five generations highlights this tradition. Risaldar Altaf Hussain Shah of 36th Jacob’s Horse of Kohat died in August 1918 in Egypt. The regiment’s British officers took care of his son, Pir Abdullah Shah, who joined the 14th Scinde Horse as a commissioned officer and fought in the Second World War. In 1947, when his regiment was allotted to India, he joined the 10th Guides Cavalry of Pakistan. His three sons; Brig. Gen. Hassan Shah, Maj. Taimur Shah and Lt. Hussain Shah joined the 10th Guides Cavalry. Hussain Shah was killed in action in the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war. Pir Abdullah Sha’s grandson, Lt. Col. Pir Israr Shah, and his great grandson, Capt. Zarrar Shah, also served in the Guides Cavalry.

Notes:

M. S. Leigh. The Punjab and the War (Lahore: Government Printing, 1922)

Lieutenant Colonel W. J. Keen. The North West Frontier Province and The War

Lieutenant Colonel J. W. B. Merewether and Frederick Smith. The Indian Corps in France (London: John Murray, 1919)

Tan Tai Yong. The Garrison State: The Military, Government and Society in Colonial Punjab, 1849-1947 (Lahore: Vanguard Books, 2005)

David Omissi. The Sepoy and The Raj: The Indian Army, 1860-1940 (London: The MacMillan Press, 1994)

Colonel H. C. Willy. History of the 5th Battalion 13th Frontier Force Rifles 1849-1924 (London: The Naval & Military Press, Reprint of 1929 Edition)

Lieutenant General S. L. Menezes. Fidelity and Honour (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999)

Jarboe, Andre Tait, ‘Soldiers of Empire: Indian sepoys in and beyond the imperial metropole during the First World War, 1914-1919” (2013). History Dissertations. Paper 11.http://hdl.handle.net/2047/d20003087

Alexander Davis. The Empire at War: British and Indian Perceptions of Empire in the First World War. Thesis for Bachelor of Arts degree, University of Tasmania, October 2008.

The author wishes to thank Lieutenant Colonel Zahid Mumtaz for providing details of family of Colonel Pir Abdullah Shah.

This article was originally published in Commemorative Edition November 1918 – November 2018 of Durbar: Journal of Indian Military Historical Society. Volume: 35. No. 2.