East Asia exhibits a vast seascape rather than landscape by most of Asian, African and European states. Except for Laos and Thailand, all other states in East Asia have sea openings; in fact majority of them are islands as well as archipelagoes. The seas surrounding the East Asian states and the narrow straits passing from different choke points play a pivotal role in the economic well-being of these coastal states. Owing to the importance associated with the seas, East Asia is strewn with multiple maritime discords amongst its different states. For instance North Korea and South Korea are yet to concur over conclusion of their maritime borders, South Korea and Japan have disagreement over a group of islets in the Sea of Japan, Japan and Russia disagree over the islands dividing the Sea of Okhotsk, China and Japan had contesting claims over the Senkaku islands in the East China Sea. But the most scintillating dispute is in the South China Sea, (SCS) between China and five littoral states surrounding the sea, that is, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan. The two distinctive features of the SCS issue unlike others are: It’s a multilateral issue rather than bilateral; the intensity of this conflict can invite the US into the picture anytime.

China accosts two issues of different nature in the SCS. With five littoral states it has overlapping claims over the ownership of islands in the sea whereas its interpretation on the Freedom of Navigation (FON) in Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) created under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) differs with that of the US. Thus the five littoral states along with the US pose two different challenges to China’s sovereignty and historic claims in the SCS. Though China’s claims on the SCS are as old as the hills but the issue got prominence after the implementation of UNCLOS in 1994 and the decision of International Court of Justice in July 2016. The status quo in the SCS not only strengthens China’s position vis-à-vis the US but enmeshes a sound opportunity for China becoming a regional hegemon.

The South China Sea—A Strategic Treasure Trove

The South China Sea possesses colossal strategic importance due to its geographical position. In simple terms the SCS melds the Persian Gulf with the Pacific Ocean. In a broader context the Persian Gulf through the Strait of Malacca opens in the South China Sea where its confluence with the Pacific along with the East China Sea (ECS) takes place. Following four significant features highlight the enormous importance of the SCS in the region:

1. Efficient Connectivity

The SCS provides the shortest path to East Asian ports from the Persian Gulf through the Strait of Malacca. Though two other alternatives also exist: first, from the Persian Gulf to Indonesia’s Strait of Sunda or Lombok passing south of the Philippines into the Pacific towards East Asia; second, proceeding from Australia towards the South Pacific to reach East Asia. Owing to being the shortest as well as the most efficient route, the SCS through the Malacca Strait is the preferred option either entering or leaving the East Asian seas.

2. Trading Hub

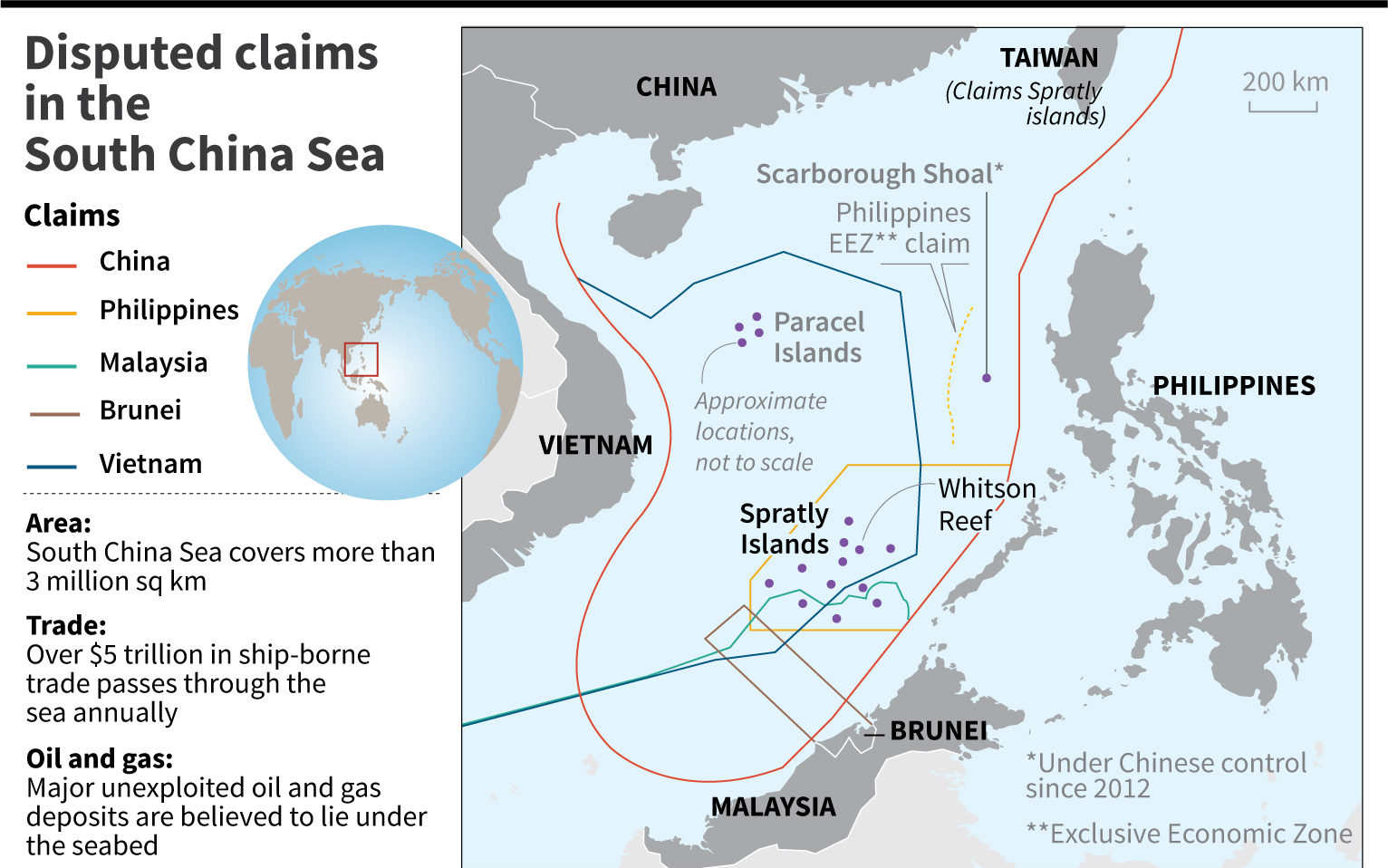

An estimated $5 trillion of shipping trade passes through the SCS every year. Roughly two thirds of South Korea’s energy supplies, 60 percent of Japan’s and Taiwan’s energy supplies and 80 percent of China’s crude oil imports come through the SCS. Unlike the Persian Gulf where only energy is transshipped, the SCS is used for energy and finished as well as unfinished goods. Numerically 100,000 ships pass through the SCS per annum / 275 per diem thereby depicting round-the-clock involvement of the SCS in commercial activities of the region. Much of this trade travels to and from China.

3. Hydrocarbons’ Heaven

Besides the proven oil reserves of seven billion barrels various astonishing estimates have been stated by different organizations. The Global Times has reported untapped reserves of natural gas from 23 to 30 billion tons whereas some other Chinese estimates have revealed 130 billion barrels of oil in waters in the SCS. If the Chinese calculations are not assumed to be apocryphal, then the South China Sea possesses the second largest oil reserves in the globe after Saudi Arabia.

4. Fish-Plethora

For a country like the Philippines fishing plays an important role in vitalizing its economy. Some 1500 species of the fish, in cornucopia, can be found in the waters of the South China Sea. The fish-abound South China Sea is not only the source of income for fishermen of coastal areas but it boosts the exports of respective states. Besides ample fishing, some 60 species of birds feed in the South China Sea.

China’s Historic Claims

China, the largest East Asian state has historic claims on sovereignty over the resources and discretion in the South China Sea; it also calls its claims irrefutable and not worthy of any debate. China’s claims cover large swathes of the SCS under its historic line in a grand loop called “nine-dash line” due to depiction of covered area in the map by nine dashes. Though some Chinese maps have also shown ten as well as eleven dashes while encompassing the entire area. Owing to its shape the nine-dash line loop is also called as “cow’s tongue” and “U-shaped line.” The cow’s tongue historically claimed by China in maps encloses an area roughly between 80–90 percent of the SCS.

China claims incontestable sovereignty over the South China Sea by over and over again calling as well as proving its claims historic. As maintained by Robert Kaplan in his writing: “Chinese analysts argue that their ancestors discovered the islands in the South China Sea during the China’s Han dynasty in the second century BC. They add that in the third century AD a Chinese mission to Cambodia made accounts of the Paracel’s and Spratlays; that in the tenth through fourteenth centuries during the Song and Yuan dynasties many official and unofficial Chinese accounts indicated that the South China Sea came within China’s national boundaries; that during the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries the various maps of the Ming and Qing dynasties included the Spratlays in Chinese territory; and that in the early twentieth century during the late Qing dynasty the Chinese government took action to exercise jurisdiction over the Paracel’s. This is to say nothing about the de facto rights Chinese fishermen have enjoyed in the South China Sea for centuries and the detailed record they have kept of islands, islets and shoals”.1

While reiterating its historic claims in the South China Sea, a document submitted by China in the United Nations in May 2009, expressed its historic claims in the SCS as:

“China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof. The above position is consistently held by the Chinese Government and is widely known by the international community.”2

The South China Sea possesses “limbs-like” importance in the geography and geopolitics of China evinced from a statement of Chinese navy Commander Wu Shengli at a forum in Singapore. “How would you feel if I cut your arms and legs?” “That’s how China feels about the South China Sea,” replied the commander when asked about China’s stance on the South China Sea.

China’s Verve for the South China Sea

China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea and its intractable stance are production of multiple factors based on its past chronicle, domestic issues, security milieu and future needs. The important factors behind China’s emotional and assertive attachment with the South China Sea are explicated below:

1. Rancorous Past

China has a nightmarish history of foreign depredations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the 19th century it lost huge swathes of its territory: the Southern tributaries of Nepal and Burma to Great Britain; Indochina to France; Taiwan and tributaries of Korea to Japan; and Mongolia and Ussuria to Russia. The twentieth century reminds China of the bloody takeover of the Shandong Peninsula and Manchuria by Japan from the heart of China. The Western states also took over the control of Chinese cites under the treaty called as “Treaty Ports.” China’s dismemberment seemed imminent at that time had the foreign burglary continued for some more period.

China now views the South China Sea as a bulwark against foreign forces after recalling its rancorous past. Surrendering its claims in the SCS is equivalent to relinquishing its cities and seaports. Patently the SCS provides a shield to China against the US-led security threats and probable forays.

2. Unmolested Passage

Sovereignty in the SCS provides a smooth sailing of goods and energy from and to China. Its ships travel to and fro from the SCS without being interdicted. Therefore relinquishing its sovereignty means handing over the control of its ships to US-aligned coastal states.

3. Malacca Dilemma

Chinese oil reserves account only 1.1 percent of world’s total whereas it consumes 10 percent of the world oil production and 20 percent of all the energy consumed on the globe. Crude oil from the Persian Gulf has to pass through two narrowest choke points: Strait of Hormuz and Strait of Malacca. The former is mostly controlled by Iran whereas latter is the entrance Strait in the SCS crossing Singapore by voyage through the South western side of Malaysia. Iran, in the past, had time and again threatened for closing the Strait of Hormuz owing to its nuclear crisis and threat of preventive strikes from Israel. But no similar threat from Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore has ever been hurled for the Strait of Malacca due to relative calm in Southeast Asia. However if such threat appears anytime in future it will cripple China’s standing because of its over-dependence on the Persian Gulf oil. This scenario is called as China’s Malacca Dilemma Reliance on the narrow Malacca Strait for its oil imports from the Middle East. The other two routes are also available from the Persian Gulf to Chinese ports, as explained above, but they involve en route two major allies of the US, scilicet, Australia and the Philippines thereby making matters worse for China. If the astounding estimates of hydrocarbons in the SCS prove true in future then China’s Malacca Dilemma will be alleviated to a greater extent besides converting China into a self-reliant oil state.

4. Security Dynamics

East Asia is home to two treaty states of the US—Japan in the North and the Philippines in the South. The US has defense obligations with these two states besides cozy relations with all claimants in the South China Sea, Vietnam Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan. China’s sway in the SCS impedes the intervening ability of the US on behalf of its allies in the case of conflict or crisis. Besides the US forces in the Western Pacific for multiple purposes cannot conduct their requisite tasks uninterruptedly and intrepidly. On the other hand if China surrenders its claims, the US will expand its missions in the SCS, not least the military ones, in a glabrous manner. The US views the Chinese’ claims as a severe impediment to its security plans and accomplishing the defense needs of its allies and partners. The SCS is the only maritime area under the sun where the US grapples for its supremacy. Beijing’s claims in the SCS solidify its position against Washington besides presenting an entirely different security outlook—the one in which the US plays the second fiddle. John Mearsheimer writes this situation as “An increasingly powerful China is likely to try to put the US out of Asia, much of the way the US pushed the European powers out of the Western Hemisphere. Why should we expect China to act any differently as the US did?”3

5. Nationalism

Attached with the South China Sea are emotions of the Chinese who display unmatched elan while talking about the SCS. The Chinese government under President Xi Jinping has successfully commingled this international issue of the SCS with domestic politics and depicted the SCS as pride of China. Therefore Beijing will never even think of relinquishing any of its claims in the SCS.

Bones of Contention

China confronts two different issues in the South China Sea. Its issues with the five littoral states and the US are entirely different. With littoral states, sovereignty and occupation of the three major islands namely Paracels, Spratlys and Scarborough Shoal define the crux of crisis. China calls these islands Xisha, Nansha and Huangyan respectively. The overlapping claims in disputed islands can be broadly categorized as:

(a) The Paracel Islands are claimed by China and Vietnam.

(b) The Spratly Islands are claimed entirely by China, Taiwan and Vietnam, and in part by Malaysia, The Philippines and Brunei.

(c) The Scarborough Shoal is claimed by China, Taiwan and the Philippines.

The Paracel’s and Scarborough Shoal are controlled by China whereas the Spratlys are possessed, in parts, by all claimants except Brunei. Dispute between China and Taiwan also exists on the Pratas Islands in the northern part of the South China Sea but the former does not consider it as a significant issue owing to non-recognition of the latter as an independent state.

Whereas with the US, the different interpretation of the Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOS) in Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) permitted under the UN-mandated Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the apple of discord between both the major powers.

China versus Littoral States

The five littoral states, that is, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei, have overlapping claims for the possession of afore-stated islands. By dint of being weaker to an incomparable extent, they all have arrayed themselves against China. The US enjoys convivial relations with these states and they all consider Washington’s help and involvement in region as the ultima ratio in case the situation aggravates further. The geographical, demographical and political aspects of these states play an important role in determining their overall position on the SCS dispute. Case by case study of the each state is given below:

1. Vietnam

Vietnam dominates the western edge of the South China Sea. It has a bitter history with its northern neighbor China owing to multiple invasions of the country in the past. The South China Sea is of prodigious importance to Vietnam as one-third of its population lives in coastal areas and maritime sector comprises 50 percent of Vietnam’s GDP. It claims the Paracel Islands, in full, and some features in the Spratlys. It refutes the Chinese claimed cow’s tongue by calling it China’s “historic dream” against the phrase “historic claim” put forward by China. Expressing loath towards Chinese nomenclature it calls the South China Sea as “East Sea” owing to its own geography. Hanoi considers the sea expansion of China as Pax Sinica and has called for curbing the sea expansion of its northern neighbor. However its cruddy experience of the Vietnam War in the previous century raises suspicions over the future US support and intentions in the region. The location of China’s Hainan Islands in front of Vietnam greatly perturbs its claims. Vietnam, a battle-hardened state is supposed to be the toughest of all the opponents in the SCS as scholars Clive Schofield and Ian Storey write “If China breaks off Vietnam they’ve won the South China Sea.”4

2. The Philippines

Geographically the Philippines is in the strongest position in the South China Sea as it dominates its eastern portion. It calls the South China Sea as “West Philippines Sea.” The Philippines, a state with more than 100 million inhabitants relies on the SCS from fishing to oil exploration: it imports all of its oil by sea. It claims 53 features in the Spratlys chain along with the Scarborough Shoal. The loss of the Spratlys and Scarborough Shoal would be a death blow to its economy and future plans. Its erstwhile President Benigno Simeon Aquino III (2010-16) planned stamping out poverty through oil and gas reserves in the South China Sea. The Filipinos say “The most important thing for us to do as a nation is to explore for oil and gas in the West Philippines Sea, because we are the poorest country in the Western Pacific.”

Manila is the only overlapping claimant in the SCS having mutual defense treaty with the US which was signed in 1951. Nevertheless its relations with the US have declined during the last few decades. Once in the mid 1990s, US military assistance to the Philippines zeroed out because of closure of its two bases namely Clark and Subic. The US has expressed its commitments with 1951 US-Philippines defense treaty but the epithets of incumbent Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte hurled against the US leaders have undermined the durability of this treaty.

3. Taiwan

Taiwan possesses a unique position in the South China Sea. In the map it can be viewed as an extension of two arch-rivals in East Asia: China and Japan. It seems the centre point of the entire sea region from the East China to South China Sea. Taipei has a very little chunk in the ongoing conflict, it occupies the Taiping Island commonly called as Itu Aba in the Spratlys. However its major issue with China is against the aim of subsuming Taiwan in its territory by China. The US gives enormous importance to Taiwan not least the Taiwan Strait separating China from Taiwan. If China engulfs Taiwan it would be spine-chilling for the US and its allies as the SCS route towards two major US allies in Northeast Asia namely Japan and South Korea would then be dominated by China. Keeping in view the important position of Taiwan, former US assistant secretary of state of East Asia Paul Wolfowitz once called Taiwan as “Asia’s Berlin.”

4. Malaysia

Malaysia, encompassing the Malay Peninsula and the northwestern coast of the island of Borneo retains a golden position owing to the Malacca strait joining the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea. Malaysia is located in V-shaped manner in south of the SCS. Almost one-fourth of its estimated 30 million population is ethnic Chinese thereby raising chances for a suspected China-supported uprising. Kuala Lumpur has military warmth with Washington witnessed by the frequent visits of US ships and submarines to Malaysian ports. It claims twelve features in the Spratlys but unlike Vietnam, the Philippines and Taiwan it has not shown aggressiveness in its claims. Dzirhan Mazadir, a consultant defense specialist, once said “We emphasize deterrence and readiness vis-à-vis China we are not looking for a fight.”

5. Brunei

Brunei shares the southeastern side of the South China Sea having claim on a single feature in the Spratlys called Louisa Reef. Brunei, an oil-rich state, has remained calm, composed and collected while raising its claim in the SCS. In fact it’s the only claimant state with no military occupation of any feature in the sea. Bandar Seri Begawan has aligned itself with rest of the claimants because of similarity of the claims and conflict nonetheless.

China versus the US

Geographically the US is not a part of Asia but it retains some major maritime interests in the Asian seas. Its position on contesting claims by littoral states in the South China Sea against China is not as aggressive as in the other arenas like trade. With China its controversy in the SCS hovers around the interpretation of Article 58 of the UNCLOS. The differing interpretation of the US and China has accrued mano a mano situation between the ships and vessels of both states multiple times in the past. Before proceeding to the core of US-China issue in the SCS, it’s imperative to define UNCLOS and EEZs.

UNCLOS—The Global Seas Law

UNCLOS is a UN-mandated Convention on the Law of the Sea explicating maritime boundaries of coastal states, types of maritime features, maritime zones created by maritime features, rights of landlocked states and related necessary issues. It was opened for signatures in December 1982 and enforced in November 1994. China is a party to the UNCLOS whereas the US Senate is yet to ratify the UNCLOS membership.

The Part V of the UNCLOS gives birth to concept of “exclusive economic zones” in Article 55 and the two subsequent articles define the rights of coastal states in EEZ and jurisdiction of EEZ. The Article 58 refers to the rights and duties of other states in EEZs. In simple terms Exclusive Economic Zones encompass from land a sea territory of 200 nautical miles equivalent to 370 kilometers (1 nautical mile = 1.852 kilometers). As per UNCLOS, coastal states have sovereign rights in their EEZs for exploration, exploitation, conservation and management of living and non-living natural resources besides managing activities for economic exploitation for instance production of energy from hydro, tidal and geothermal means.

Differing Interpretation

Apropos the rights of other states in EEZs, the US and China are sharply as well as scathingly divided. China views that coastal states reserve the right for regulating foreign military activities in their EEZs like surveillance, patrols and others of foreign ships and vessels. The US, on the other side, holds that UNCLOS grants sovereign rights to coastal states in their EEZs on economic activities only broadly entailing oil exploration and fishing; EEZs have nothing to do with regulation of foreign military activities. Washington emphasizes for innocent passage of both civilian and military vessels from EEZs of coastal states. China’s stance is supported by 27 states prominent being: Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Iran, Malaysia, North Korea, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Thailand, UAE, Venezuela and Vietnam. In other words, if support in terms of world’s populace is considered then Beijing’s viewpoint gets an out-and-out support of more than 55 per cent of world’s population. China’s stance in the words of one Chinese diplomat is, “Freedom of navigation does not mean to allow other countries to intrude into the airspace or the sea which is sovereign. No country will allow that. We say freedom of navigation must be observed in accordance with international law. No freedom of navigation for warships and airplanes.”5

The US replies China by calling its definition of Freedom of Navigation, FON, as “narrow” and has coined the phrase “Freedom of the Seas” an alternative term for freedom of navigation. By freedom of the seas, the US encapsulates all the prerogatives and lawful maritime and airspace uses including military ships and aircrafts guaranteed to all nations under the international law. Peter Dutton, a retired US Navy international lawyer in an article wrote:

“The creation of the exclusive economic zone in 1982 by UNCLOS was a carefully balance compromise between the interests of the coastal states in managing and protecting the oceanic resources and those of maritime user states in ensuring high seas freedom of navigation and over fight, including for military purposes. Thus in the EEZ the coastal state was granted sovereign rights to resources and jurisdiction to make laws related to those resources, while high seas freedom of navigation were specifically preserved for all states to ensure the participation of maritime powers in the convention.”6

The US-China discord over the FON has led to some major maritime skirmishes between them during the last two decades. Most of those incidents had happened during President Obama’s tenure who was accused of maintaining a flaccid policy against China in the SCS. Had Donald Trump been the US President at that time any of the minor tiffs could have morphed into a full scale war owing to Trump’s insular stance against China evinced from his trade war against the Asian giant.

The nebulous wording in Article 58 of the UNCLOS has germinated a war front between Washington and Beijing in the SCS. Para 1 of the said article reads:

“In the exclusive economic zones, all states, whether coastal or landlocked, enjoy, subject to the relevant provisions of this convention, the freedom referred to in Article 87 of navigation and over flight and of the laying of submarine cables and pipelines and other internationally lawful uses of the sea related to these freedom, such as those associated with operation of ships, aircrafts and submarine cables and pipelines, and compatible with the other provisions of this convention.” 7

The article bristles with evasiveness, needless repetition and it requires a holistic exposition of the phrases: other internationally lawful uses of the sea; associated with operation of ships; compatible with the other provisions of this convention. Who will determine other internationally lawful uses of the sea? Which types of operations of ships are associated with the Freedom of Navigation? Is there any international authority for adjudicating the compatibility of actions with the other provisions? These are some questions which appear in mind after reading this article. Had the phrase “freedom of navigation for military purposes is permitted/not permitted” been used, it would have solved the quandary. Though the Article 87 has been referred for freedom of navigation but again it focuses on freedom of over flight, laying submarine cables and pipelines, constructing artificial islands and other installations, fishing and scientific research. In Article 95 warships in the high seas have been granted complete immunity from the jurisdiction of any state except the flag state, but here the phrase “high seas” carries contesting meaning for the US and China. The US refers entire sea area as the high seas regardless of the area covered in exclusive economic zones or even in territorial sea, 12 nautical miles from the coast of a littoral country. Whereas China refers the sea outside EEZs as the high sea.

The differing and conflicting interpretation of various provisions coupled with US desire for command and control in the SCS by sailing its military ships without respecting the maritime zones could have disastrous consequences. In continuation of sophistry transpicuous from US’s attitude in the other international treaties, the US has signed but not ratified the UNCLOS. But the successive US governments have emphasized the other states for implementation of UNCLOS in true letter and spirit. Can a non-follower of international law apropos the global seas urge other states for proceeding as per the law?

UNCLOS and Nine-Dash Line

The nine-dash line of China in the South China Sea permeates the exclusive economic zones of five littoral states. As explained earlier, China calls its claims historic, irretrievable and non-negotiable; whereas its high-level authorities have repeatedly called the UNCLOS as “inconclusive” when it comes to decision of historic rights and claims. The argument put forward vociferously by Beijing is that the UNCLOS cannot take into account China’s historic claims and nine-dash line: the nine-dash line predates UNCLOS for four decades and China’s historical rights predate UNCLOS for centuries, ergo the UNCLOS provisions cannot be applied here with retroactive effect for deciding the fate of China’s centuries long sovereign rights and claims. Simply China’s claims supersede the UNCLOS. In manifestation of its stance, China repudiated its participation in arbitration sought by the Philippines in 2013 against China’s historic rights and violation of maritime entitlements at the Scarborough Shoal. China questioned the jurisdiction of tribunal for deciding the fate of historic rights. Though the tribunal continued its proceedings without China’s participation and it issued its verdict in favor of the Philippines in July 2016; China refuted to comply by calling the judgment as “a piece of Kleenex.” China’s vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin called it nothing more than a waste paper and one that would not be enforced by anyone. The Chinese were also dissatisfied with the presence of a Japanese judge in the tribunal owing to inimical relations and the trenchant past between China and Japan.

US Stance on Overlapping Claims

The US has maintained an ambivalent stance over resolution of disputes in the South China Sea. The US, being a non-party to UNCLOS, has stressed for resolving the issues as per international law. Nevertheless Washington takes no position on competing claims to sovereignty over disputed land features in the South China Sea. US policy in the SCS broadly encompasses: amicable resolution of disputes, support for freedom of sea involving both sea and air-based use, use of international law for resolving bilateral/ multilateral maritime disputes, consistence of maritime claims with international law; forsaking provocative ex parte actions, and finally unqualified military activities in EEZs of other states.

Double-Peaked Military Strategy

The littoral states surrounding the South China Sea including Singapore, a non-claimant for any feature in the SCS, have warmth with the US. They all believe that if China’s trespasses further in its designs and objectives or shows bullying aggression, the US will reply sternly on behalf of them. Their belief cannot be refuted owing to US interests in region. The double-peaked US military strategy for the SCS entails: Enhancing the maritime military capabilities of coastal states; and increasing the presence of US ships, vessels and personnel in the region. Greater interoperability, integrated operations, combined exercises and imparting maritime domain awareness have been the key objectives of US maritime policy for littoral states in the SCS. Implementation of first parameter has witnessed a non-linear increase in presence of submarines and radars in the SCS acquired by coastal states particularly Malaysia and Singapore. The multi-million dollar US-Malaysia military deals also include training of Malaysian army. In fact Malaysia is called the quietest and most reliable partner in the South China Sea. The US‘ tacit support to Taiwan is regardless of the SCS dispute as already explained that prevention of Taiwan becoming China’s territory is its policy objective. The Philippines enjoy a defense treaty with the US but the US-Philippines relations have taken a nosedive during the tenure of incumbent Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte which could improve any time soon in future if China utterly bars Filipino fisherman for fishing in region around the Scarborough Shoal.

The second parameter of US double-peaked policy is strengthening its own military presence in the SCS. The Obama administration announced a major shift “from Atlantic to Pacific” in its naval posture in July 2013. President Obama’s National Security Advisor Susan E. Rice while announcing the shift in US policy had stated:

“We are making the Asia-Pacific more secure with American alliances and an American force posture that are being modernized to meet the challenges of our time. By 2020, 60 percent of our fleet will be based in the Pacific and our pacific command will gain more of our most cutting-edge capabilities.”8

The Obama administration had also announced “pivot to Asia” and rebalance strategies both focused security reassurance to allies and partners by active engagement in the South China Sea. The importance of the SCS region can be gauged from “immune-status” granted by the Obama administration from reduction in defense outlays in the Pacific.

Probable US involvement in the conflict

Except for minor dust-ups, the SCS region is free from any major conflict malagre involvement of two major powers. However the US can incite a major dispute if any of the following takes place:

a. Passage/Entrance of US military ships in the territorial sea (12 nautical miles) or closer to any installation of China;

b. Its security commitments with the Philippines may invoke military conflict in the region.

As explained earlier, multiple little-intensity squabbles in the past between China and the US have time and again taken place in the SCS owing to differing interpretation of freedom of navigation. Despite harsh rhetoric against China over the SCS issues, the Trump administration had been chary of conducting freedom of navigation operations in the region in its early months. It did not authorize a single FON operation in first four months. But during the subsequent 10 months (May 2017–March 2018) it allowed six FONs: three, two and one in the Spratlys, Paracel’s and Scarborough Shoal respectively. All the three operations in the Spratlys were within 12 nautical mile range of Mischief Reef, a low tide elevation turned into an artificial island by China. During all the six FONs by the US, the Chinese ships warned them for leaving the intruded zones which they did immediately; failing that a severe clash would have transpired immediately. If Washington plans further FONs in future in territorial sea or any of the island, rock, low tide elevation or other installation, seemed important by China, and shows brittleness by refusing return of the entered warships, the crisis could transmogrify into a high-calorie conflict accruing war between both the states.

On the other hand, the Article IV of 1991 US-Philippines treaty reads:

“Each party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific Area on either of the parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common dangers in accordance with its constitutional process.”9

Simply an attack on the Philippines will be treated as an attack on the US and vice versa. In the existing state of US-Philippines relations Manila may not deem an attack on Washington’s ships or personnel as on their owns’ but the US has reaffirmed its commitments multiple times for security of the Philippines under its defense treaty. If a clash between the Chinese and Filipino vessels takes place and the Philippines knocks on the US door for fulfilling its security commitments under defense treaty then surely the US will intervene on behalf of its security partner and a direct confrontation between Beijing and Washington may happen.

RIMPAC without China

US Defense Secretary James Mattis has remained vocal against China in his rhetoric and admonished the Asian giant for curbing militarization of the South China Sea or face dire consequences. Ostensibly he played a major role in turnaround displayed by the Pentagon for China’s participation in biennial Rim of the Pacific, RIMPAC, exercises held in June 2018 involving twenty four states for US-led joint naval drills in the Pacific. The prominent participants being the US, the UK, Australia, India, South Korea, Japan, France and four littoral claimants in the SCS except Taiwan. Initially Pentagon invited China for participation in RIMPAC exercises but later on it disinvited on the pretext of militarization of the South China Sea by China. A statement from US Department of Defense DOD reads.

“As an initial response to China’s continued militarization of the South China Sea we have disinvited the PLA Navy from the 2018 RIMPAC exercise. China’s behavior is inconsistent with the principles and purpose of the RIMPAC exercise.”10

China had participated in the last two RIMPAC exercises held in 2014 and 2016 but this year’s China-less RIMPAC showcases a different but unyielding and bellicose stance of the US. Since most of the RIMPAC participants have estrangement with China so China’s participation would have provided an excellent opportunity for harmonizing its naval relations with RIMPAC partners. East Asia, where maritime security is of prime concern owing to overlapping claims and acrimonious past among coastal states, would have benefitted a lot from China’s participation as cordial relations among the navies would drastically reduce the chances of misperception and misjudgment. Absent China from the RIMPAC, means preparation for war as mala fide intentions against China are deduced from the US-led RIMPAC.

South China Sea—A Choice Between Gloomy and Halcyon Days

The South China Sea predicament presents an extremely volatile situation in East Asia. The contesting claims of littoral states and China, and divisive interpretation of freedom of navigation by China and the US could have catastrophic upshots. Perhaps a war is brewing in the seas surrounding the coastal states in the SCS and it could irrupt any time on a subtle issue or slight miscalculation. China will not relinquish an inch of maritime territory under its nine-dash line hypothetic claim in the SCS whereas the US will not accept its decline-oriented China’s claims. Eventually the entire region will witness new or solidification in existing anti-China US-led military alliances and agreements. Besides, the SCS region will witness an increase in up-to-the-minute submarines, surveillance vessels, patrolling boats, joint military drills and related security-enhancing measurements in the days to come.

However the conclusion of a defense treaty between the US and any coastal state will intensify the ongoing crisis and be considered by China as “an overt preparation of war by the US” in the SCS. Defense treaty will put obligation on the US for defense of its ally in case of crisis like that of Japan and the Philippines. In fact a new defense treaty will give the US a war ground with China in the SCS which its existing defense treaty with the Philippines may not yield in near future owing to declining state of US-Philippines affairs. Taiwan and Malaysia will be preferred options for the US for any future defense treaty: Accessibility in the Taiwan Strait and dominating the Malacca Strait will define the case for any such treaty. Though the US does not have official relations with Taiwan but the Taiwan Relations Act and the Trump administration’s enacted Taiwan Travel Act may pave the way for spawning a new era between Washington and Taipei.

In the light of US’ non-membership of UNCLOS, China rightly questions the validity of US suggestions for resolving disputes in the SCS as per international law. The US Senate must ratify the UNCLOS without any further delay and a framework for freedom of navigation, including both commercial and military vessels, may be drafted by all states in the region. Prima facie the Chinese interpretation for freedom of navigation seems more logical as unrestrained entrance of foreign military ships and vessels in the territorial sea region or even in exclusive economic zone of any state signals some venturesome military objectives; the same can be legalized through prior notification or permission from the particular coastal state. Concluding a common interpretation for freedom of navigation would be a major repellant to war in the SCS and is not a gigantic or unachievable task but it requires resolve among states for preventing the region from war-like crisis.

Questioning with aggression the sovereignty claims of China in the SCS as per “cow’s tongue” would act as casus belli. China aims for retention of maritime territory in the SCS and it can surpass any limit for maintaining the status quo in the South China Sea: its repudiation of ICJ’s July 2016 decision in favor of the Philippines is testament to this fact. Therefore pressing China for surrendering its historic claim is tantamount to star-gazing. Rather the coastal states, being on receiving end, along with the UNCLOS-ratified US, may opt for sharing of hydrocarbons and the fish stock in the SCS under the supervision of China. The sharing criteria can be devised for a definite time, say 5-10 years, keeping in view proximity of exploration site with exclusive economic zones, economic status of coastal belt, population density of coastal regions and other factors as agreed upon by the states surrounding the SCS. Though Beijing has declined, in the past, for sharing of the SCS resources but the UNCLOS-ratified, new and conciliatory US posture can compel China for reconsidering its previous statements.

Undoubtedly the SCS is an empyrean for littoral states and it must be utilized for peace and prosperity only: Individual progress engenders collective prosperity. Militarization of the SCS with military paraphernalia would stifle the chances of glorious and wealthy future from all states. The South China Sea in its current situation is a powder keg which can lead to a full scale war any time in the future. And if war happens no state would ripe fruits from the SCS. The US must recalibrate its South China Sea policy by realizing the eternal truth that SCS is the only region in the globe where it cannot preside over the proceedings; rather it’s China here on the US’ seat. Therefore by realizing its secondary position it must display an impartial role in the region. A favorably changed US stance and posture in the SCS could dramatically alter the entire scenario and avert the war-probability to a marvelous extent.

References

1 Robert D. Kaplan, “Asia’s Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of The Stable Pacific,” Random House International Edition, New York 2014.

2 Communication from China to the United Nations dated May 7, 2009.

3 John J. Mearsheimer, the Tragedy of Great Power Politics, W.W. Norton, New York, 2001.

4 Clive Schofield and Ian Storey, “The South China Sea Dispute: Increasing Stakes and Rising Tensions,” Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC, November 2009.

5 Jim Gomez, “Chinese Diplomat Outlines Limits to Freedom of Navigation,” Military Times, August 12, 2015.

6 Peter Duton, “Three Disputes and Three Objectives: China and the South China Sea,” Naval War College Review 64, no.4 (Autumn 2011).

7 Article 58, “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,” November 1984.

8 Susan E. Rice, “America’s Future in Asia,” November 20, 2013, Georgetown University.

9 US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty, signed August 30, 1951.

10 DOD Statement, “China disinvited from Participating in 2018 RIMPAC Exercise,” USNI News, May 23, 2018.