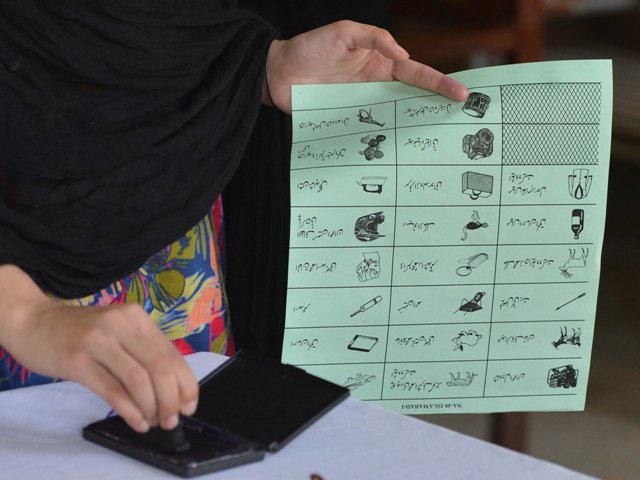

Winners and losers of Elections 2018 have kept up the national tradition, whereby the winners praise the elections while losers reject it. Participation in the elections was enormous, and nationwide. According to Election Commission of Pakistan, voter turnout was over 55.8 percent while over 47 percent women also cast their ballot. For the 272 general seats in the National Assembly, 3,459 candidates were in the run including 1,623 from Punjab, 824 from Sindh, 725 from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and 287 from Balochistan. In case of general seat of provincial assemblies, 4,036 candidates contested for 297 seats in the Punjab, 2,252 for 130 seats in the Sindh; 1,165 for 99 seats in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and 943 candidates for 51 seats in the Balochistan. Over the years, conducting elections is becoming more and more a security enterprise; over 371,000 soldiers were deployed for security duties, including their presence inside each polling station.

Keeping in view diametrically opposite stance on the credibility of elections by the two sides Winners and Losers it may be too early to pass an accurate judgement about its level of fairness; more so when Pakistan has a history of controversial elections. And in most controversy related cases, credible evidence to support the rigging claims surfaced too late to benefit the aggrieved party; conscience of the whistle blowers, more often than not, pricked too late to be of any practical use. The only exception to this pattern was Election 1977. When, after the national assembly voting, the losing side walked away enbloc from the remaining process, boycotted the provincial elections scheduled on third day of rigged national assembly polls. Political conglomerate, Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) took a two track approach, negotiating for settlement backed by a peaceful, yet paralysing protest movement. Their effort dragged on for a long time and in the meanwhile the military walked in. Rigging allegations in most of such controversial elections have generally proved to be right.

However now the environment does not support a 1977 like scenario, PMLN and PPPP are looking forward to coexist with PTI’s federal setup provided the latter lets them have their safe heaven, Punjab and Sindh respectively, with a reasonable free hand. If this combination gets a sustainable traction, then agitations will be confined to a few small parties which will not be able to mobilise worthwhile public support. However, if PTI chooses to hitch up only one of the two main rivals, most likely the PPPP, then the other would join the smaller parties and carry forward the agitation to a reasonable degree. Hence, in either of three combinations, no countrywide agitation is foreseen, at least in the immediate timeframe. The scenario could change dramatically if a credible whistle blower, like a senior insider of ECP comes up and puts forward sufficient evidence in support of rigging. The situation in Sindh is quite clear i.e. PPPP would form the provincial government; in Punjab, much will depend whether PTI takes a statesmanlike approach to let PMLN form and run the government or take a short sighted approach of installing its own government by wooing smaller groups who are dying to come forward and do poodles.

International assessments in the run-up to Election 2018 were hardly kind towards Pakistan’s democratic system and associated processes. Most of the predictions pointed towards a military engineered hung parliament leading to a weak government, which would remain bogged down with its day to day survival, leaving the political arena free for the military’s interventions as an accepted norm. Every Tom Dick and Harry liked to play the theme of pre-poll military intervention in favour of Imran khan. In all likelihood, the theme was over played. And there were different voices as well. For example in an interesting July 23 piece for Aljazeera, “Is Imran Khan the Pakistani military’s favourite son’?” Michael Kugelman commented:

“Given Khan’s personality and policy positions, there’s reason to doubt that he is the army’s blue-eyed boy. A big storyline in the lead up to Pakistan’s July 25 election has been the nature of the relationship between Imran Khan, the cricket star-turned-politician and leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party, and the country’s powerful military. According to the insinuations of some top leaders with the incumbent Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) party, the military is working behind the scenes to engineer an electoral outcome that results in a government helmed by Khan. It’s a theory one could certainly call it a conspiracy theory embraced by many commentators inside and outside Pakistan. Indeed, Pakistan’s army – which has held direct power for nearly half of Pakistan’s 70-year existence, and has enjoyed an outsize role in politics when not in direct control does have a strong incentive to undercut the PML-N, with which it sparred frequently in recent years, and to help propel the PML-N’s main challenger, the PTI, to victory. However, the notion that the military would actually be comfortable with Khan as its man in Islamabad is questionable. Indeed, given considerations of personality and policy positions, there’s reason to doubt that Khan is the military’s blue-eyed boy. The army prefers a predictable and pliable civilian leader. Khan, however, is known for being mercurial and stubborn. Even some of Khan’s positive traits like his charisma and supreme self-confidence could be liabilities for the military because these qualities suggest he would be unwilling to defer to higher authority. Cult of personality types aren’t known for being submissive. Ironically, a potentially more palatable prime minister choice for the military hails from the very party that the armed forces may be trying to undercut. Shehbaz Sharif, the brother of Nawaz, would be the PML-N’s candidate for premier if it wins the election. While lacking his brother’s charisma, he has a solid reputation as a capable and steady politician and he gets along well with the military. Strikingly, in a recent interview with the Financial Times, Shehbaz Sharif called for the PML-N and the military to improve their ties. If the military truly has a favourite son, Shehbaz Sharif may have a better claim to the title than does Imran Khan. Meanwhile, Khan expresses some views that are at odds with the military’s. Khan regularly expresses strong support for Pakistan’s armed forces, and he has signalled his willingness to work with the army. “It is the Pakistan Army and not an enemy army,” he said in a New York Times interview in May. “I will carry the army with me.” In a country where the military’s tentacles extend deep into politics, such comments from civilian leaders who aspire to ascend to the top echelons of power should come as no surprise. And yet, dig a bit deeper, and the differences begin to emerge. Khan has taken strikingly positive positions towards Iran; he has lambasted US President Donald Trump for his anti-Iran speeches, and he has even said Pakistan should “become like” Iran. Additionally, Khan’s shrill and strident anti-American messaging he once vowed to shoot down American drones if he were to be in power likely unnerves the military, which hopes to salvage Pakistan’s sputtering relationship with the US. The military is firmly behind these counterterrorism efforts and welcomes the “American money” that helps finance them. Earlier this year, however, Washington suspended $1.1bn in aid amid worsening US-Pakistan ties. In early 2018, Khan repeated his criticism that Pakistan shouldn’t be fighting its own people’s However, given his personality, it’s hard to imagine him happily ceding ground and giving in to the military; he’s more likely to defy than to defer. Accordingly, there’s a strong possibility that a Prime Minister Khan would spar with the military, exacerbating tensions in a civil-military relationship that already experienced ample strain during the last few years of the PML-N-led government. Such a dynamic could usher in a fresh period of political volatility in Pakistan. Ultimately, for Pakistan’s military, the type of government is more important than the person that leads it. A weak and divided coalition is easier to influence and exploit than is a strong and united administration”.

Notwithstanding the strong perception about Imran Khan’s under the table relations with the military are likely to persist. Ironically, he will be faced with an uphill task to recover back the authority on foreign policy and security related domains that military was able to wrench from the PMLN government due to leverage provided by Imran Khan’s long sit-in, during 2014, in Islamabad. People will wait and see how his fresh equation with military evolves.

The prospective Prime Minister’s victory speech was reassuring and refreshing. Hopefully, he won’t get bogged down in cosmetics and would go ahead with substantive reforms. Likewise, the tone of All Parties Conference indicated that the losing elements are more likely to settle down with fate accompli after making face saving noises.

With elections 2018 Pakistan has transitioned from a two to three party political system as for as Federal government making is concerned. Pattern of split mandate federal government not forming its own party governments in all provinces has sustained itself. Religious Right as well as remnants of the Left politics stand routed. Karachi is liberated from a four decades long pervasive and perpetual ethnic tainted fear. And the “Jeep” mystery stands buried, deep down, under the weight of people’s mandate. Alongside, myth of military supported parties and individuals also stood exposed.

A distinctive feature of voting this time was unpredictability. The surveys and impressions were generally subjective, rather than reflective of likely voter behaviour. A three-way party contest has its own complexities and, besides, there were so many spoilers. Most analysts played safe by suggesting a razor sharp contest by placing the three main contenders at around 70 National Assembly seats, and drawing a scary confrontational scenario with competing smaller parties in King Maker role; lucky that it did not happen so. The bloodiest elections of Pakistan’s history ended with usual political undertones. On the Election Day 31 people were killed in a suicide bombing in Quetta, a stark reminder of the security challenges facing the new government.

With Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf poised to form the new governments at the Centre and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, all other major parties across the country have cried foul over attempts to rig the elections and blamed the ECP for failing to conduct transparent polls. As usual, the Election Commission was quick to reject the allegations, it blamed National Database & Registration Authority (NADRA) for the delay in result announcement saying that the NADRA communication device did not function well. NADRA rejected the EC claim a familiar post election blame shifting environment in Pakistan.

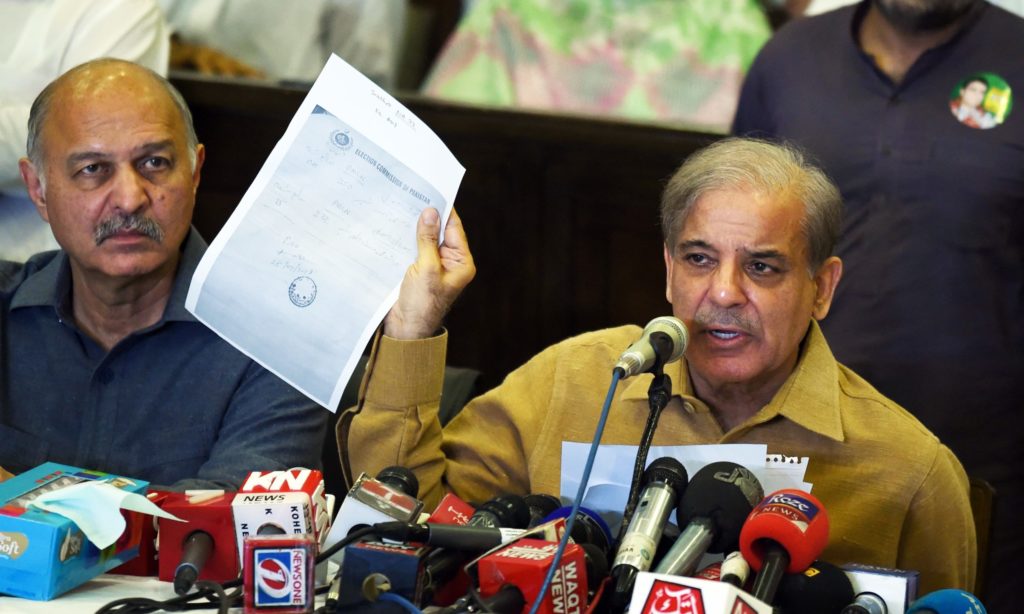

Polling was conducted peacefully in most parts of the country, with no major incident of rigging reported during the day. However, while the vote count was still under way, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz the main contender to the PTI rejected the election results and said: “Rigging has been committed in the elections. The puppet mandate [to PTI] is not acceptable. We will only accept the people’s mandate. It is unfortunate that the people came out of their homes to cast the votes in such a harsh weather but their mandate was stolen.” He announced that his party would adopt all available political and legal options, as “we cannot leave that matter like this”. He hinted at a joint strategy by taking on-board other complainant parties. The Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), Muttahida Majlis-i-Amal (MMA), Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan (MQM-P), Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP), Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party (PkMAP) and Balochistan National Party-Mengal (BNP-M) also raised almost similar complaints of foul play.

Most parties have claimed that their polling agents were forced out from polling stations without being provided with Form 45 (the statement of vote count) by presiding officers. Speaking on the occasion, PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto tweeted: “It’s now past midnight & I haven’t received official results from any constituency I am contesting myself. My candidates [are] complaining polling agents have been thrown out of polling stations across the country. Inexcusable & outrageous.”

The silver lining was that, in a historic first, women in some conservative parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab came out to cast their votes as candidates sought to fulfill the legal requirement of minimum 10 percent women’s turnout to validate their result. Women in tribal areas and other conservative areas had traditionally been barred from voting in the past general elections, as the practice of keeping women from voting had been a well-entrenched norm under verbal and written agreements between candidates and family elders in such areas. For the first time in the country’s electoral history, the ECP had annulled the result of Dir Lower (PK-95) by-polls in 2015 after finding that none of the registered women voters had cast votes. This deterrence has worked. In Balochistan, too, women voted in numbers.

The real hero of 2018 Election was the electorate the commoners in the street. In a bitterly polarised environment and biased predictions, the voter could not be restrained even by harsh weather. Voter was, by and large, disciplined and composed, indicating that electorate duly value their right to vote. This sort of commitment of the people will add resilience to our democratic process.

Perception has it that democracy in Pakistan is continuation of interplay between the filthy rich, moderated by institutions, with people’s wellbeing a low priority item on their agenda. It is indeed a dangerous assertion that has undermined Pakistan’s democracy, within and its image projection outside the country. Reality is that a typical Pakistani commoner has consistently and courageously demonstrated a commitment to the electoral process. There is a strong and visible change in the behaviour of Pakistani people where they have started questioning the time tested political leaders for non-delivery over their promises. This has led to defeat of previously tested political leaders and erosion of major political parties.

A few factors made these elections unpredictable: behavior of the voter falling in age bracket of 18 and 29, pre elections surveys on this count were, by and large, non-professional and judgmental; although there was a strong perception that youth may vote for the PTI, there was equally strong likelihood that, like earlier elections they could be tamed by their elders; number of contestants was un-precedently high, especially with religious affiliations and those disgruntled party ticket hopefuls whose wish was not granted by their respective parties; most of them contested as independents. They were expected to erode the voters of their ex- parties, there was a perception that those using the “Jeep” symbol were military establishment supported, and that Jeep group could emerge as a political force to reckon with. Likewise there were different scenarios being postulated with regard to Karachi, all hoping retention of overall Muhajir texture in one form or the other. Electorate shattered all these myths, and threw up clear mandate for parties rather than individuals.The PML-N is known for having an efficient and well tested electoral machine and for mastering the art of election-day activism. It had announced to undertake discrete measures to counter rigging, but it did not work and PML is one of the most articulate claimants of rigging. Three party contest was expected to throw up surprises, and it did.

Now the genie is out and it can’t be forced back into the bottle so everyone has to eventuality adjust to the reality. The so-called pre-poll rigging failed to achieve the objective of fractured mandate leading to a shaky coalition of the unwilling. The Federal government is poised to be fairly stable, at least initially; and so is the situation in KP and Sindh. Split mandate in Punjab may continue to make interesting turns on a day to day basis. Balochistan has its own dynamics where stability would rest of a proportionately huge conglomerate style cabinet. The post tooling and retooling has begun to put in place viable governments.

Challenges facing the federal government are phenomenal. Inter-institutional wrangling, inefficient bureaucracy, politicised police, corrupt revenue system lethargic lower judiciary, well entrenched corruption in Public Procurement System, unsustainable Defence spending, Current Account Deficit of US$ 18 billion, dysfunctional power transmission and distribution system, circular debt approaching Rs 700 billion, external and internal borrowing crossing 40 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), bleeding State Enterprises, resurgent terrorism and looming water shortage are some of the domestic challenged. External challenges are equally problematic: President Trump and Prime Minster Narendra Modi are unlikely to ease their squeeze; IMF conditions for bail-out are likely to be tougher than ever; exiting out of vicious cycle of Financial Action Task Force (FATF) listing is another daunting task; externally sponsored cross borders terrorism is unlikely to end any time soon, return of Afghan refugees is not in sight, so on and so forth. With an anti-status quo mind-set and promises of tall reforms agenda, the platter of the new federal government isany way over loaded.

Like all contemporary modern democracies, Pakistani version of democracy has its peculiarities whose roots are firmly grounded in historic, socio-economic, cultural and sectarian dynamics. Its best feature is that people are spring-loaded towards the democratic process. They have made a couple of very powerful rulers quit through peaceful urgings. They abhor inefficient and corruption tainted governments and are also not kind towards electoral rigging and governance failures. They are short on patience with regard to non-performing governments for which a typical tolerance time is of 2-3 years. Generally, people want unacceptable regimes to change through electoral process but when in terrible mood there are some isolated voices for military takeover as well. Governments are made by rural vote, which is captive to ethno-sectarian and local power dynamics; and governments are toppled through urban agitations which have dubious promotors, financiers and string pullers.

Typical span of a military takeover has been around a decade. Despite some of the very good development works and efficient governance, all ex-military rulers are publically condemned to the derogatory term “dictator”. Military rulers may have ensured a semblance of efficient governance, better revenue collection and financial discipline; they all lacked political acumen and made mistakes, some of which were indeed political blunders. Towards their fag end they were all found hobnobbing with same “dirty politicians” for prolongation of their rule. As a general practice, the judiciary’s role has been opportunistic (with rare exceptions), it routinely sanctifies all successful regime changes under one pretext or the other and condemns them only when “usurper” has either departed or his power has declined beyond redemption. The media is still struggling to achieve a balance between “truth” and “accepting compensation” for not telling the truth while the Social Media is a typical representation of a dangerous trend of misplaced power without responsibility and accountability; while truth is still busy putting on its boots, falsehood reaches half of the World.

The relationship between formal and informal State institutions is more often bumpy, and harmony is a rarity. These entities are often seen making alliances amongst themselves to paralyse functioning of remaining institutions. None of the duly elected Prime Ministers and most of the Parliaments could not complete their terms. And, most of the times transition has been problematic. Need was felt to amend the 1973 Constitution 31 times; of these, the processes reached logical end 25 times. Majority of these amendments hovered around rewriting inter-institutional balance; most of such efforts were subsequently undone and at times redone. Lax criteria and poor scrutiny allows shady persons to become a lawmaker. Making it to parliament by such people is seen as strengthening their positions in the local fiefdoms and covering own criminal trails; when in parliament, they do not support governance and transparency friendly law making.

Tendency of amassing political power within family has touched dangerous proportions, politics of “electables” have made the political parties captive to, say, a dozen of families, whose members are found at leading tiers of all mainstream political parties; no matter which party come to power, the strategic interests of these families are perpetually protected at the cost of well-being of a common man. Smaller political parties play the role of King Makers when there is no clear winner; and their political broker like leaders extract much more power than their legitimate share.

Most people blame certain apolitical institutions for making the polls controversial, but one cannot altogether absolve the politicians of the mess in which we have ended up. A significant section of our political leadership has a track record of entering into marriage of convenience with the entities notorious for interfering in the elections; and especially so when they find that they have no chance of winning the electoral race through fair and transparent process.

National political leadership has repeatedly failed to lead the nation and bridge differences to ensure stabilization of political processes and strengthen democratic institutions. This is a well-known fact that all candidates use all means at their disposal to win the elections, be they fair or unfair; and at the end of the election the winner individual or party is crowned for rigging. Crying foul is a common feature in such elections the World over, some real some fictions. Accusations of Russian inference in the US elections and Pakistan’s interference in recent elections of Indian state of Gujarat are some contemporary bizarre examples.

The new government may not be able to resolve most of these daunting problems but it cannot afford to leave any one of mentioned issues unattended. While appearing in a struggle to overcome all the challenges, the government must prioritise a few vital areas to mitigate the hardship of under privileged segments of masses.

While there are credible domestic and international concerns that polls were rigged in favour of PTI, overall, Election 2018 has enhanced the national stature at home and abroad and improved Pakistan’s image amongst the comity of nations. The need of the hour is that the victorious parties and individuals must approach politics with a more democratic and conciliatory spirit. And for losers: for the sake national stability, politics must not be allowed to return to an era of open warfare akin to 1990s. Hopefully, all political parties and political individuals will soon put behind post electoral bickering and reconcile to the realities that be. We wish good luck to the new governments and expect them to do well.