Historical Perspective

By the year 1978, western powers considered Iran as a stable and trusted ally in Gulf region. Armed with sophisticated and most modern warfare weapons made in US, the oil-rich state had a highly specialized army and an efficient and dreaded secret police, the Savak.

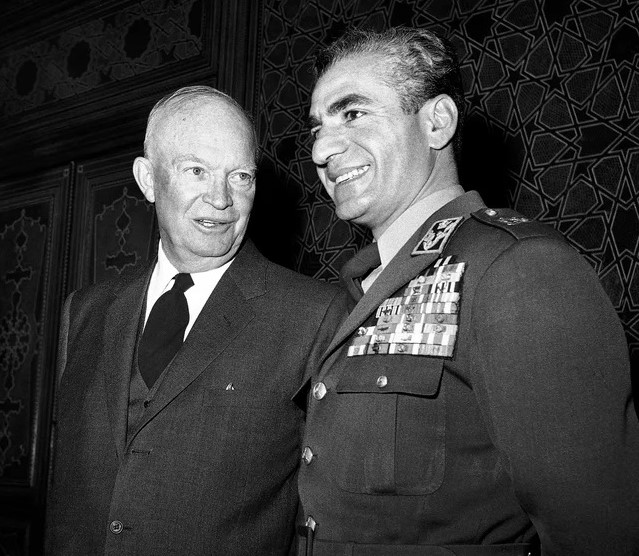

Raza Shah Pehlavi was the supreme leader of Iran, he was commonly known as the Shah of Iran (King of Iran)1. The Shah was totally reliant on its western allies for maintaining his power inside Iran and gaining influence over regional and neighboring countries. This was one source of anger in the Iranian people, which later resulted in anti-western sentiments and public protests. Some other events also fueled anger against Iran’s western allies:

1. Britain’s meddling in Iran during its 19th century power struggles with Russia in Central Asia.

2. Britain and the United States jointly sponsored a coup in 1953 that ousted the democratically elected prime minister, Mohammed Mossadeq. This was termed as CIA’s first overthrow of a foreign government.

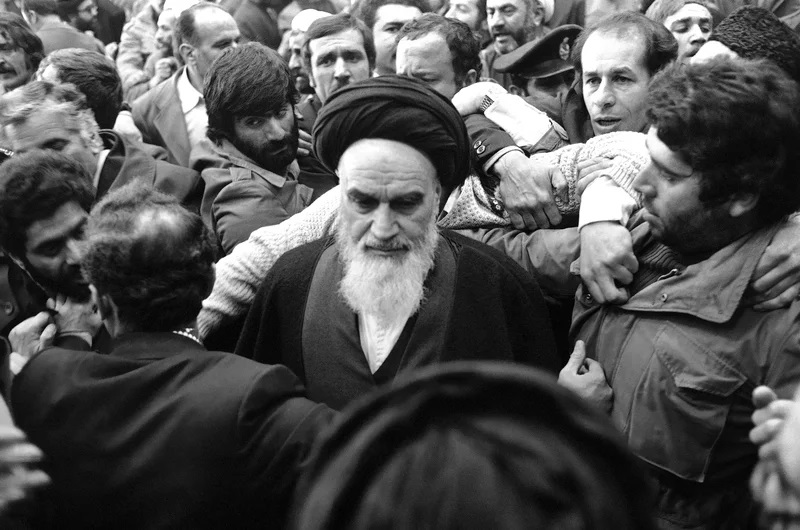

Collectively all this resulted in mass civil disobedience and public demonstrations in Iran. Ten years later in 1963 the Shah’s so-called White Revolution and series of modernizing reforms brought him into conflict with an angry clergy (the mullah) from the dusty town of Khomein in central Iran the hometown of Ayatollah Khomeini. Infuriated at government encroachment on traditional areas of clerical responsibility, notably education and family law, Khomeini publicly denounced the Shah. His subsequent arrest sparked three days of rioting that left hundreds dead. He was sent into exile the following year. With cosmetic modernization in the upper class while life of the ordinary citizen lingered at the lower stream spawned a sense of frustration among the people. With the passage of time the Shah had started exercising authoritarian rule. The oil boom of 70‘s that quadrupled Iranian revenue and poured billions of dollars in the national exchequer enabled Raza Shah to indulge in luxury. Public opinion was generally suppressed and whoever dared speak against the government had either to face imprisonment or he had to flee from the country. The Shah practiced zero tolerance for people who spoke against him or his government. Ayatollah Khomeini was the only one who was successful in maintaining his struggle. Gradually the Shah’s very close associates fled to the US and Britain following his extreme and unwarranted attitude and ruthless exercise of power.2

“Mohammed Reza Shah’s rule of Iran from 1942 until 1979 spanned eight U.S. presidents. His desire for military supremacy over his neighbors and his distrust of the Soviets led him to seek a military relationship with the United States following the end of the Second World War. As the U.S.-Iranian relationship developed, the idea of arming Iran came to form a key component of U.S. policy due to waning U.S. options in the Gulf through the 1960s and an alignment in U.S. and Iranian regional policies in the early 1970s. This relationship eventually resulted in Iran wielding a military that was, on paper, within reach of becoming the world’s fifth-most-advanced force in 1978.”3

In January 1969, Richard Nixon was elected as president of the United States of America, by the time Iran was already America’s single-largest arms purchaser. In late 1972 Nixon leveraged U.S. Middle Eastern regional policy primarily around the focal point of a militarily strong, pro-American Iran. Concurrently, the Shah was encouraged and empowered to begin an unprecedented and virtually unbalanced military spending spree in what is now known as the “blank check.”4

Nixon had practically envisioned the future course of American involvement in gulf politics. He did this for two reasons,

1. Taking advantage of the situation while the British decided to withdraw their military forces from the Gulf, leaving behind a vacuum.

2. The Vietnam quagmire stressed the limits of the direct application of U.S. power in peripheral areas. Iran seemed the obvious candidate to turn to.

There was a legacy of U.S. investment going back to the 1953 coup that the CIA engineered with the British to restore the Shah’s autocracy after a left-leaning nationalist government had marginalized him. The other US allies in the Middle East were left alone, like Saudi Arabia was weakened by military redundancy and political instability. If the Americans opted for any other ally in the region such as Israel, then it would risk pushing the Arab states further towards the Soviet bloc.

In 1972 the Shah of Iran purchased more than $3 billion dollars worth of arms from the United States within in a short span, which was comparatively twentyfold increase against the previous year. For the remainder of the 1970s, the Shah continued to buy arms in the multibillions per annum, dwarfing all other U.S. allies such as Israel and the NATO countries.

Experts were concerned about US option to choose Iran as the primary vehicle for outsourcing containment and policing in the Gulf, while Iran’s role was quite controversial in its essence in the region, due to following reasons:

1. Iran was not an Arab nation like the majority of its neighbors.

2. The Iranian religious population was comprised of Shia Muslims rather than the regionally dominant Sunnis.

3. Under the Shah’s rule, Iran was widely perceived as an arrogant and status-quo-threatening regime by its neighbors.

“In sum, the Shah’s Iran was neither respected nor liked in the region. Therefore, investing in promoting Iranian hegemony as a proxy for American power was at odds with the reality in the wider region.”5

After Nixon, Gerald R. Ford assumed office as the thirty eighth President of the United States. During his period by 1974 Congress had begun to recover lost ground in Gulf. Congress remained in confrontation with the Ford Administration on military sales to Iran, primarily due to huge amount of arms supplied to Iran. Nixon kept the congress in the dark and no one was aware what was actually going on the sidelines of US-Iranian relations. The arrangement was kept secret.

Washington had practically set up the Shah as a regional policeman who was willing to accept this position with its huge oil revenues. An over estimated supply of arms to Iran by the US was a partial factor for the drift of anti-American sentiment that sustains in Iran even to this day. Experts believe that if the Shah had not been overthrown by the Iranians themselves in 1979, it is likely that wider regional opposition would have manifested to the Shah’s ambitions as his plans became ever grander. For those reasons, Nixon’s blank check and the policy package that resulted became extremely risky.6

In 1979, the Right Wing Ayatollah Rohullah Khomeini returned from exile and became the Supreme leader in Iran as a religious guide and an interpreter, while the Shah was forced to flee Iran on the outset of pre-revolution arrangements. The US embassy was stormed by fundamentalist Iranian students who took the US embassy staff hostage demanding return of the Shah of Iran, the seizure went on for 444 days. By 1980 US cut diplomatic ties with Iran seizing most Iranians assets in US while blocking trade and commercial activity. The US hostage rescue mission which was ordered by President Jimmy Carter failed and further action was called off when US gunship helicopters crashed in sandstorms, at the cost of eight US servicemen. When US tactical and diplomatic efforts failed Iran released U.S. hostages. Ronald Regan assumed office as US president and former US president Jimmy Carter was defeated in elections. Three years later US branded the Iranian State a sponsor of terrorism.’ Intelligence reviews always suspected US-Iran relations to be dubious, calling them as a ‘friendly enemy‘, most of the experts believe that there always remained a relation between Iran and the US administration to some level. In 1986 President Reagan struck a secret arms deal with Tehran in violation of the arms embargo, money from these sales were spent secretly on US sponsored anti-communist guerillas in Nicaragua. In the year 1988, a US warship shot down an Iranian passenger plane killing 290 people onboard. Even after such a horrific incident the newly elected Iranian President Ali Akbar Rafsanjani tried to resuscitate secret contacts with the US:

“ Ali Akbar Rafsanjani, president from 1989 to 1997, initiated secret contacts with the Americans to receive arms during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, provoking the so-called Iran-Contra affair. After the 1991 Gulf War between the US and Iraq, I interpreted for him at a conference in Tehran when Rafsanjani told an audience of foreign security experts that “Iran could accept the reality of the presence of US military forces in the Persian Gulf”, although in public Iran was completely opposed to their presence.”7

Soon after the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US, President George W. Bush termed Iran, Iraq and North Korea as an ‘axis of evil’, at the same time accusing Tehran of building a secret nuclear weapons program. The claim was later endorsed by a US based Iranian exile group that was opposed to the government in Tehran, disclosing that Iran had two previously hidden nuclear facilities under construction: a uranium-enrichment plant at Natanz and a heavy water-moderated nuclear reactor at Arak. The United States was against any kind of nuclear build-up in Iran. Later in 2006, the United States conveyed its willingness to join multi-lateral talks with Iran if it verifiably suspended it nuclear enrichment program. The following year Iranian foreign minister Manoucher Mottaki and US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice had a brief meeting on the sidelines of the Egypt Conference at Sharam Al Sheikh.8 A US based National Intelligence group predicted that Iran was working to develop nuclear weapons by fall of 2003. The suspected Nuclear weapons program was later halted to convince President George W. Bush for negotiations. Under Secretary of State Bill Burns was sent for the first time to directly take part in negotiations with Iran in Geneva on the nuclear issue. In 2009, Barak Obama assumed office as President of the United States, he told the leadership in Tehran that the United States would extend a hand of friendship on the condition that Tehran would convince its allies that it is not building a nuclear bomb. Unfortunately, the efforts proved to be fruitless when France, Britain and the United States revealed that Iran was building a secret uranium-enrichment site at Fordo near the holy city of Qom. Iran later maintained that it had already disclosed the site to the UN Nuclear watchdog for inspection. For the next three years negotiations between the West and Iranian officials came to halt. In 2012, the US and Iranian officials began secret talks which intensified in 2013 on the nuclear issue. In due of course of time Hasan Rouhani (commonly considered to be a pragmatist) in Iran was elected President. His primary aim was to improve Iran’s relations with the world and boost trade and economic activity but his aim would only be possible by easing sanctions imposed due to its nuclear program. On 28 September 2013, President Barak Obama and President Hasan Rouhani talked on the phone, this was termed as the first highest level contact between the two countries in decades.

The Joint Plan of Action (JPOA)

Hasan Rouhani believed that to revive Iranian economy and to bring back Iran into the mainstream global politics, Tehran had to make some major compromises on its nuclear program which remained crucial for negotiations on any level. In November 2013, A US-Iran secret deal materialized, Iran and six other major powers reached an interim pact called the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA) under which Iran agreed to curb its nuclear program in return for limited relief in sanctions. The other six powers were the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia. The JPOA finally came into effect in 2015 when Iran agreed to a long-term deal on its nuclear programme with the P5+1 group of world powers the US, UK, France, China, Russia and Germany. Under the accord, Iran agreed to limit its sensitive nuclear activities and allowed international inspectors in return for the lifting of harsh economic sanctions.

Iran had two major nuclear facilities Natanz and Fordo where uranium hexafluoride gas was fed into centrifuges to separate out the most fissile isotope, U-235. Low-enriched uranium, which has a 3% to 4% concentration of U-235, can be used to produce fuel for nuclear power plants. “Weapons-grade” uranium is 90% enriched. In July 2015, Iran had almost 20,000 centrifuges. Under the JCPOA, it was limited to installing no more than 5,060 of the oldest and least efficient centrifuges at Natanz until 2026 i.e. 15 years after the deal’s “implementation day” in January 2016. Iran’s uranium stockpile was reduced by 98% to 300kg (660lbs), with a condition that the volume may not increase until 2031. It must also keep the stockpile’s level of enrichment at 3.67%. By January 2016, Iran had drastically reduced the number of centrifuges installed at Natanz and Fordo and shipped tonnes of low-enriched uranium to Russia. In addition, its Research and Development facility was been limited to Natanz Nuclear Facility until 2024. Nuclear enrichment would be restricted at Fordo Nuclear Facility until 2031, and the underground facility would be converted into a nuclear, physics and technology center. The 1,044 centrifuges at the site will produce radioisotopes for use in medicine, agriculture, industry and science.

Arak heavy water reactor and production plant

Iran had been building a heavy-water nuclear facility near the town of Arak. Spent fuel from a heavy-water reactor contains plutonium that is suitable for a nuclear bomb. Threatened with possible buildup of nuclear bomb by Iran, the US and its allies wanted this facility to be dismantled immediately due to proliferation risks. With an interim nuclear deal agreed in 2013, Iran contracted not to commission or fuel the reactor while further assuring the JCPOA that it would redesign the reactor to reduce the risk of any weapons-grade plutonium and stop its production. The remaining fuel would be sent out of the country as long as the modified reactor exists. Iran was further restricted to build any additional heavy-water reactors or accumulate any excess heavy water until 2031 from its aides.

The Obama Administration further assured its allies that the JCPOA would prove to be a comprehensive agreement which would prevent Iran from building a nuclear programme in secret. Through this Iran allowed international inspectors for an “extraordinary and robust monitoring, verification, and inspection”. Inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) would continuously monitor Iran’s declared nuclear sites, in addition the agency would verify that no fissile material was moved covertly to a secret location for building a bomb. Iran also agreed to implement the Additional Protocol to their IAEA Safeguards Agreement, which allows inspectors to access any site anywhere in the country they believe suspicious. Until 2031, Iran would have 24 days to comply with any IAEA access request. If it refused an eight-member Joint Commission including Iran would decree on the issue and decide on punitive steps, including re-imposition of sanctions.

Isfahan Uranium Enrichment Plant

Before July 2015, Iran had a large stockpile of enriched uranium and almost 20,000 centrifuges, enough to create 8 to 10 bombs, according to the Obama administration. US experts projected that if in any case, Iran had decided to rush to make a bomb, it would take two to three months until it had enough 90% enriched uranium to build a nuclear weapon.

Natanz uranium enrichment plant

The Obama administration maintained that the JCPOA would remove the key elements such that Iran would need one year or more to create a bomb. The agreement further refrained Iran from engaging in any kind of research and development activities which might help in the development of a nuclear bomb.

“In December 2015, the IAEA’s board of governors voted to end its decade-long investigation into the possible military dimensions of Iran’s nuclear programme. The agency’s director-general, Yukiya Amano, said the report concluded that until 2003 Iran had conducted “a coordinated effort” on “a range of activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device”. Iran continued with some activities until 2009, but after that there were “no credible indications” of weapons development, he added.”

Economic fallouts for Iran

Sanctions have had a drastic impact on the Iranian economy previously imposed by the UN, US and EU in an attempt to force Iran to halt uranium enrichment. It cost Iran more than $160 billion (£118 billion) in oil revenue from 2012 to 2016. Under the deal, Iran gained access to more than $100 billion in assets frozen overseas, and was able to resume selling oil on international markets while using the global financial system for trade. If in any case, Iran failed to comply with any aspect of the deal there was an established automated system by which the sanctions would be imposed for next 10 years, extendable to five more years. If the Joint Commission could not resolve a dispute, it would be referred to the UN Security Council. The deal stipulated continuation of UN arms embargo on the country for up to five years, although it could end earlier if the IAEA is satisfied that its nuclear programme is entirely peaceful. A UN ban on the import of ballistic missile technology will also remain in place for up to eight years.

The US drift on Iran’s Nuclear Deal

On 20 January 2017, Donald J. Trump assumed office as President of the United States. He was elected on the a slogan to ‘Make America Great Again.’ Soon after Trump’s assuming office, Iran tested a medium-range ballistic missile, the Trump administration reacted and put Iran on a watch list and maintained that Iran should be held accountable for disciplinary action.

On 18 July 2017 at the G-20 summit, Trump urged all foreign leaders attending the summit to avoid doing business with Iran. Iran took issue with the move saying it violated the United States’ end of “the bargain.”9 The very next day, renewing its role in the agreement the US administration at the G-20 summit disclosed a series of non-nuclear related sanctions against Iran, blaming that Iran’s actions “undermine regional stability.”10 In the beginning of 2018, the US administration warned it would withdraw from the agreement unless flaws in the deal were reworked. President Trump revealed that he was in negotiation with his administration and in talks with European allies on a revised deal that would impose further sanctions if Iran ventured to test another long-range missile. This situation gave rise to great concern amongst the European leadership who were worried of the outcome and after effects in case the US withdrew from the deal. The French President and German Chancellor Angela Merkel tried to persuade Trump to remain part of the deal and not jeopardize the multinational accord. A week later Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in a televised presentation accused Iran of lying about its nuclear weapons capabilities and urged the United States to withdraw from the deal. President trump endorsed Netanyahu‘s claims and emphasized that Iran possesses nuclear weapon capability. On 8 May 2018, Trump announced the United States withdrawal from the nuclear deal and re-imposition of sanctions on Iran.

European Concerns on Iran: Challenges for US

“More than a generation of European leaders and diplomats were engaged in the talks at one time or another.”11

European leaders claimed that it was their decade old struggle to convince Iran to come to terms for making a deal on Joint Plan of Action for Nuclear non-proliferation. They insisted that it was primarily to maintain peace in a troubled region and that a generation of leadership have invested their time and energy in negotiation and talks at one time or another. On the contrary the Trump Administration and other American critics link this deal solely to Obama.

“Indeed, in European foreign policy circles, the deal was considered the most significant achievement of European diplomacy in living memory.”12

The general feeling in Europe about the deal was promotion of peace and not about the pursuit of economic opportunities for Europe. Hence, the Europeans believed that if the US withdrew from the deal it would be a big upset for European diplomacy for maintaining balance of power in the Gulf region. The Middle East is already at war in Syria, Saudi Arabia is going through a transformation period, Iraq is not stable yet where small uprisings and social unrest still prevails in the country.

“European leaders’ overarching goals in the Middle East are to de-escalate the hegemonic struggle between Iran and Saudi Arabia, prevent nuclear proliferation, combat terrorism, and stanch the flow of refugees into Europe. But many of these goals are now being actively undermined by the Trump administration, which has made a show of siding with Israel and Saudi Arabia against Iran in regional conflicts from Yemen and Iraq to Lebanon and Syria.”13

The international community turned down the US idea of withdrawal and imposing new sanctions on Iran while four major US Allies Israel, UAE, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia supported the US.

Conclusion

“It started in 1957,” he says, “and ironically, it is a creation of the United States. The U.S. provided Iran with its first research reactor a nuclear reactor, a 5-megawatt nuclear reactor that is still functioning and still operational in Tehran.”14

From very beginning the United States and Iran were on sort of a love-hate relationship. National interests are supreme while friendships are temporary in theory of international relations. Donald Trump believed that his idea of ‘Making America Great Again’ might be attained through war or confrontation, hence his threatening the global peace. Iran on the other hand had not stopped its nuclear program except for the period the deal (i.e. JCPOA) was signed since 2015 till date. The European are furious, with a US withdrawal, Iran would possibly restart building its nuclear enrichment and that may result in some uneven equation in the region. In its squabble with Israel, Iran has been attacking Israel but that does not translate into any victory for Iran. Israel may have a reason for joint action against Iran and may form a new coalition as a counter measure. The United States for the sake of global peace will have to rethink its strategy on JCPOA, it may annoy its European partners. In Iran President Rouhani and Foreign Minister Javad Zarif have a weakened position due to possible US withdrawal from JCPOA. The hardliners in Iran urging the present leadership not to trust the US. If the US does not comply with the deal there will be a possibility of a new nuclear arms race in the region that may further worsen unrest in the region.

End Notes

1 By the time there was no constitutional position of Kingship in Iranian constitution, Mohammad Raza Shah Pehlavi was self-proclaimed Supreme leader and King of the Iranian republic.

2 David Patrikrakos, The last days of Iran under Shah, 7 February 2009

3 Stephen Macglinchey, How the Shah Entangled America, The National Interest, 2 August 2012

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

7 Benafsheh Keynoush, The secret side of Iran-US relations since 1979, The Guardian, 10 July 2015

8 Mariun Karouny, Rice meet Syrian minister greets Iranian, Reuters, 3 may 2007

9 Laura Figueroa Hernandez May 08, 2018 2:09 PM

10 Ibid

11 Mathew Kartschnig, Trump Nukes Europe’s Iranian Dream, Politico, Berlin, 9 May 2018, https://www.politico.eu/article/trump-nukes-europes-iranian-dreams/

12 Ibid

13 Mark Leonard, How Europe save the Iran Nuclear Deal, Project Syndicate, 30 April 2018, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/how-europe-can-save-the-iran-nuclear-deal-by-mark-leonard-2018-04

14 Steve Inskeep, Born in the USA: How America created Iran Nuclear program,www.radio.wpsu.org, 18 September 20