International agreements play an instrumental role in resolving the decades-long inimical issues amongst the states which otherwise would have never been resolved besides bloating the bad blood between them. These accords, either bilateral or multilateral, have drastically scaled down the prospects of World War III involving major powers. The US being the sole super power, after the breakup of former USSR, has a key role in almost all such agreements but it’s history, under Republican presidents, bristles with abrogating the treaties and accords. The era of President George W. Bush (2001-2009) witnesses the demise of two major US’s bilateral treaties in the arena of arms control and non-proliferation: Anti Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty with Russia in 2001 and the Agreed Frame Work with Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK in 2003. Had both these treaties been preserved till to-date the world would have been free of missile aggression between Russia and the US and North Korea might not have crossed the nuclear Rubicon.

Most of the arms control agreements and peace treaties are the legacy of Democratic Presidents: President Carter played a pivotal role in Camp David Accord between Egypt and Israel; the 1994 Agreed Frame Work between the US and North Korea was drafted and signed under the auspices of President Clinton and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between P5+1 and Iran can patently be called the effort of President Obama to clinch a nuclear deal with Iran. The historic nuclear accord, JCPOA, signed in the penultimate year of President Obama’s two-term tenure has major opponents in the Middle East casting aspersions on the intentions of Iran since its outset. The deal also infuriated many Republicans at that time and the Republican presidential candidate in November-2016 elections, Donald Trump, said that he would tear up the Iran deal if elected as President. Nonetheless he gave a go ahead to the deal during the first fifteen months of his tenure by waving off sanctions besides tearing down various provisions of the JCPOA but May 12 seems a decisive date for the nuclear deal as President Trump may refuse to sign sanction-waivers this time.

JCPOA may not be detrimental to the interests of the US and its allies as President Trump’s recently-fired Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and incumbent Secretary of Defense James Mattis have time and again reaffirmed the benefits of this deal to the national security interests of the US. However appointment of Mike Pompeo as the Head of Foggy Bottom replacing Rex Tillerson and the belligerent John Bolton as the National Security Advisor signals something untoward from the Trump administration in the month of May. Mike Pompeo and John Bolton are the staunchest critics of the Iran deal and their opinion converges at the point of regime change in Iran by preventive military strikes alike Iraq. John Bolton, the Bush era’s US ambassador to the UN and undersecretary of state for arms control and international security is widely known for his significant role in preparing an unneeded, unjustified and flawed case for military adventure in Iraq which was vituperated gravely in the report presented by the Iraq Study Group chaired by the former Secretary of State James Baker. Coincidently, Trump’s closest aides are disgusted at the Iran deal besides being the advocates of military strikes. The incumbent US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley, who enjoys an excellent rapport with President Trump, is no different from Pompeo and Bolton and has criticized the Iran deal multiple times at the UN forum.

On the other hand President Trump’s two major allies in the Middle East scilicet Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Saudi Arabia’s crown prince Mohammad Bin Salman are the long-time opponents of this deal and have a converging conclusion that the fiscal benefits enjoyed by Iran from this deal would solidify its nuclear and missile base for future activities besides ramping up its monetary support to non-state actors and disaffected groups in Syria and Yemen. The Saudi crown prince during his recent two-week state trip to the US cautioned that they might be in a war with Iran in the next 10–15 years. Ergo, the allies and advisors of President Trump stand on four common parameters: JCPOA serves tenebrous prospects for the US and its allies; the US must retreat from the JCPOA immediately; re-imposition of pre-JCPOA sanctions on Iran waived under Security Council resolution 2231; and military action against Iran if it continues with its nuclear and missile program. The common conclusion makes the way easiest for the US President but he must re-think JCPOA, which flat out defers the case of preparing a nuclear weapon by Iran for more than 15 years from its date of implementation. The US’ withdrawal from the landmark deal will not only destroy the strategic equilibrium created under JCPOA but a nonpareil turbulence will get its inception in the Middle East.

JCPOA—a 15-year pause to Iran’s nuclear weapon

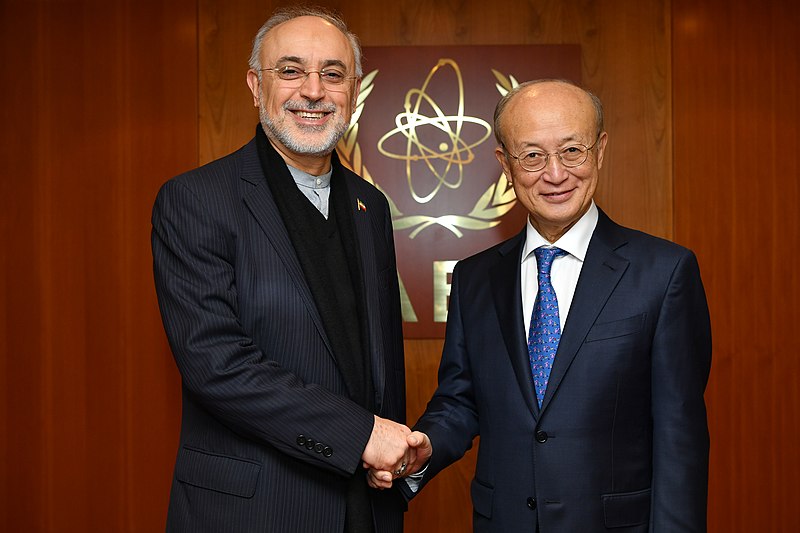

JCPOA—a lengthy-negotiated document is a legacy of President Obama encompassing cardinal role of his second-tenure Secretary of State John Kerry. Unlike the US’ bilateral 1994 Agreed Frame Work with DPRK, the JCPOA is a multilateral agreement involving five veto-yielding powers and Germany christened as “P5+1”. The accord occludes both the paths to obtaining the nuclear weapon: It places stringent limitations on uranium enrichment program; secondly it absolutely uproots the plutonium path. As per the Implementation Plan outlined in Para 34(iii) of the document, January 16, 2016 is marked as the Implementation Day when IAEA reported compliance on prime nuclear commitments by Iran to the U.N. Security Council thereby lifting nuclear-related sanctions on Iran slapped by the U.N. Security Council, the US and the EU. Nonetheless the expiration dates in both the paths are the prime causative factor for criticism by the opponents.

Limiting the Uranium Enrichment program

The historic nuclear accord between P5+1 and Iran severely restricts the uranium enrichment path towards possession of nuclear weapon. The uranium enrichment is an indispensible and inevitable step towards preparation of nuclear weapon. Two broad classifications of enriched uranium exist: Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) containing greater than 20% enriched U-235; and Low Enriched Uranium (LEU) maintaining U-235 quantity lesser than 20%. The weapon-grade HEU is believed to be enriched more than 93% in U-235 isotope. The Iran deal restricts uranium enrichment to a maximum level of 3.67% for a period of 15 years. The prescribed limit i.e. 3.67% falls under the category of LEU and it will be woolgathering to envision a nuclear weapon at this enrichment level. Besides Iran has agreed to restrict the installed centrifuges at Natanz facility to a maximum number of 5060 IR-1 and phasing out and storing the remaining installed centrifuges under the supervision and monitoring of IAEA for the next 10 years, from the implementation day. Therefore the uranium churning machines in Iran will be incapable of producing even LEU-range uranium greater than the prescribed limit of 3.67% for 15 years from the implementation day.

The nuclear accord caps the R&D programs as Iran is barred for conducting research in the fields of advanced centrifuges and isotope separation techniques for a period of 10 years from the implementation day. After expiration date Iran will lag far behind in the technological arena and most of its installed systems would be outdated. Iran has also agreed to convert its underground uranium enrichment facility near the city of Qom “Fordow enrichment plant” into a nuclear physics and technology centre. The said enrichment plant was constructed in redundancy of preventive strikes at Natanz enrichment plant. The elimination of redundant enrichment plant makes Iran’s nuclear enrichment program dearly vulnerable to preventive strikes from Israel in a manner similar to strikes on Osirak reactor in Iraq in 1981 and Al-Kibar reactor in Syria in 2007, the latter has been admitted recently by Israel’s authorities. In addition to this Iran has agreed for retention of only 300 kg uranium (3.67% enriched) for a period of 15 years. The excess uranium will either be down-blended to natural uranium or will be sold out to international buyer in return for natural uranium.

The non-proliferation experts unanimously agree that under JCPOA, uranium enrichment facilities in Iran offer no path towards preparation of nuclear weapon. The claim for use of nuclear technology for civilian purposes by any state is irrefragable and in sync with the Article IV of Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The NPT remains reticent on the number of installed centrifuges and uranium enrichment capacity. Therefore, the prescribed uranium enrichment limit of 3.67%, for a period of 15 years, depicts only the civilian use of uranium by Iran; the possibility of preparing a nuclear weapon requires enhancing the enrichment capacity to produce 93% enriched uranium. Any up-gradation of enrichment facilities during the JCPOA time limitations span, for preparing HEU, will be detected as quickly as lightning by the IAEA inspectors who possess access to disparate nuclear sites under the terms “routine” and “complimentary” access. Any suspicious nuclear site would be accessible to them within 14 days; failing that non-compliance of the accord will be reported. Under the Additional Protocol agreement between IAEA and Iran, use of nuclear technology and materials for weaponization would be detected in no time. Therefore in the existing tightest circumstances, Iran’s preparation of nuclear weapon or even retention of uranium above the prescribed level (3.67%) is not only unimaginable but if it happens it puts a huge question mark over the regime and performance of IAEA whose impeccable verification mechanism has been praised by different international organizations.

Eliminating the plutonium path to nuclear weapon

Plutonium path to preparing a nuclear weapon is considered more difficult than the uranium enrichment path owing to expertise required in mastering the back end of nuclear fuel cycle not least the spent fuel reprocessing technology. After a holistic review of JCPOA one fact becomes as clear as crystal: The nuclear accord utterly stamps out the path to preparing a plutonium-based nuclear weapon. The JCPOA weeds out the pestering proliferation concern from Arak heavy water reactor because of presence of plutonium in its spent fuel in a better proportion than that of a light water reactor. If reprocessed, the spent fuel could give weapon-usable plutonium. Iran agreed under JCPOA for redesigning and rebuilding the Arak reactor as per agreed conceptual design. The redesigned Arak reactor will be fed only 3.67% enriched uranium and will not produce weapon-usable plutonium. The spent fuel of Arak reactor will be shipped out of Iran for the lifetime of reactor. In addition to this Iran will neither engage in production of any other heavy water reactor nor in spent fuel reprocessing or construction of reprocessing plant for a period of 15 years.

These prohibitions give a deep-six to all the possibilities and paths of preparing a plutonium-type nuclear weapon besides denting the Iran’s nuclear infrastructure in a drastic manner. After 15 years, Iran will have to start from scratch as the country would be denuded of major facilities and materials required for travelling the plutonium path to nuclear weapon. The limitations on uranium enrichment facilities and elimination of plutonium path for 15 years, both from the date of implementation, uproot even the miniscule possibility of preparation or possession of nuclear weapon in that period and even soon after. Iran can acquire or prepare a nuclear weapon during this period only if it maintains a clandestine nuclear network which is well-nigh impossible during the current inspection regime under the JCPOA. Even the incumbent Director General IAEA Yukihi Amano in his multiple reports during the last two years has cleared Iran of retaining ulterior nuclear sites besides reporting its full compliance on the provisions agreed under JCPOA.

Trump’s apprehensions and baseless demands

While waiving off sanctions in January 2018, US president Donald Trump said he would not renew the sanction waivers next time if Congress failed to address his three primordial reservations explicating his loathsome attitude towards the nuclear deal. President Trump argues that: Expiration dates in tenure must be replaced with indefinite period; the US legislators must inseparably join Iran’s nuclear and missile program; and immediate inspections at all sites by international inspectors be given. A pragmatic analysis of President Trump’s three demands will reason them out as “needless, impractical and based on vinegary approach towards the Islamic Republic.”

1. Elimination of expiration dates

His first demand of supplicating expiration dates with indefinite time bears him out as an inexperienced politician and undiplomatic president living in never-never land. JCPOA-like agreements are always time-bound and are renewed, after negotiations, just before the maturity. The US-USSR arms control agreements starting from SALT-I and ABM treaty in 1972, SALT-II in 1979, INF treaty in 1987, START-I in 1991, START-II in 1993, and New START in 2009, enumerate the five-decade arms control diplomatic odyssey of world’s two major powers and can be taken as an archetype for discussing this demand of President Trump. These agreements were an outcome of continual diplomatic dialogue between the US and Russia, formerly USSR and every new agreement was the refined version of the previous one. It’s transpicuous that all these agreements gave fantastic results thereby truncating the number of offensive and defensive weapons programs and nuclear warheads from five to four digits. The firmness and durability of intentions for reducing the weaponization programs can be gauged from the fact that despite breakup of USSR into 14 republics, it continued its negotiations and clinched further agreements with the US.

In real sense, JCPOA-type agreements possess an immanent renewal capability: It’s very difficult for a party, Iran in this case, to relinquish the financial gains and restart working under the regime of sanctions once again. The monetary benefits of this accord and relieved sanctions in different sectors will place Iran in a highly advantageous economic position during the course of next 15 years. But as explained earlier, Iran will be outflanked in the nuclear world after expiration of JCPOA owing to restrictions imposed in R&D and technological sectors. So how could it be believed that the pre-JCPOA nuclear activities would get their recrudescence with same impetus in Iran after 15 years? If Iran concludes the deal in a manner its civilian nuclear needs are fulfilled especially in the field of power and medical isotopes and security dangers from the Middle Eastern states particularly Israel do not loom large then it can be presumed that Iran would opt for renewal of the deal diplomatically. Therefore it’s unwise, at this stage, to pre-decide the future of time-limitations in the JCPOA. Most probably they will be extended if the US trusts Iran and allow a lubricious path to this historic accord.

2. Nexus between nuclear and missile programs

The second demand apropos linking nuclear weapons with ballistic missiles shares some egregious input from Iran. The UN Security Council resolution 2231 not only endorses the JCPOA but encapsulates also a non-binding condition of forsaking the testing of nuclear-capable ballistic missiles by Iran. The Islamic Republic, on the other hand, has agreed to cap the range of its ballistic missiles below 2000 kilometers but continued missile testing after implementation of JCPOA. The inexorable missile testing is the major source of vexation for the US and its allies thereby placing Iran’s overall weapons program under a cloud. Tehran must clarify this matter publicly without which the US and its allies would have an unshakeable basis for fulminating Iran and the nuclear deal over and over again.

Nevertheless President Trump’s viewpoint of inextricably linking the nuclear and missile program does not hold much water. Had Iran detonated the nuclear weapon then warheads and missiles would have been linked in a manner desired by President Trump. Politically Iranian leadership is even yet to decide the preparation of nuclear weapon repeatedly conveyed from the top-tier and its supreme leader Khameini has walked an extra mile calling nuclear weapons “utterly un-Islamic.” However Iran possesses adequate conventional weapons and JCPOA-like limits on its missile program would be unacceptable for the Iranian government as it would greatly undercut its strategic calculation and capabilities, besides heavily hampering its existing deterrence posture in the Middle East. But Iran must abate continual missile testing, not least the ballistic, as missile testing not only widens the rift between the US and Iran but smells fishy on its future intentions anent preparation of nuclear weapons.

3. Immediate inspection at all sites

President Trump’s third demand of immediate inspection at all sites seems preposterous and is based on his peremptory attitude. The historic nuclear accord incorporates the routine and complimentary access of different nuclear sites under a certain time frame. Additionally the Section Q, para 74–78 (Annexure I) of the agreement is specific to activities and sites inconsistent with the JCPOA and entails mechanism for resolving any impasse between Iran and IAEA. The international inspectors have so for reported full compliance of JCPOA provisions except for the two times when amount of heavy water possessed by Iran exceeded the allowed limit; Iran promptly heeded the observations and complied positively. The concept of “anytime, anywhere” inspection as desired by President Trump is seemed to be an infringement and infraction of sovereignty of an independent state where foreign inspectors go unbridled in their routine activities. Moreover inspection falls in the domain of IAEA whose up-to-the-minute verification mechanism is robust, resilient, and reliable. Therefore, the US must leave the responsibility of inspection to the international nuclear watchdog rather than involving itself directly in the inspection matters.

Options for the US President

The options available for the Trump administration broadly vary from pulling out, re-negotiating and continuing with the deal and are explained below:

1. Pulling out of the deal

For the US president pulling out of the deal is as easy as a pie: Simply his refusal to sign the sanction waivers on May 12 will be equivalent to the US’ withdrawal from the deal as the pre-JCPOA US nuclear-related sanctions will get their instauration. Such a step by President Trump will tarnish the international image of the US in an unparalleled way besides rupturing the non-proliferation regime created after implementation of JCPOA. Two out of six P5+1 members, Russia and China, will come out in conspicuous favor and support to Iran besides heavily berating the US; whereas the UK, France and Germany, owing to their congenial relations with the US, may not express their views like Russia and China but they would be absolutely certain that the US president had not done justice with the deal. But the ghoulish prospect of this act will be the death of dealing the North Korean nuclear issue in diplomatic manner: Neither Kim Jong Un, the North Korean leader who has recently agreed for an amicable resolution of his country’s nuclear crisis and announced surprising moratorium on nuclear and missile testing, will trust the US for its nuclear dealings nor any member from P5+1 take risk for participatory and signatory role in negotiations and consequent agreement respectively. Scuttling the deal by the US president would divide the US and Iran like haves and have-nots: The US would be called the aggressor whereas Iran would be termed aggrieved. Therefore President Trump must avoid creating embolus in the path of JCPOA on May 12 by certifying the sanction waivers otherwise the US image will get an indelible scar and the world’s nuclear non-proliferation regime will be behind the eight ball besides adding one more crisis in the earth’s crises-riddled basket.

2. Re-negotiating the deal

Re-negotiating the historic accord of JCPOA addressing the apprehensions of President Trump is the second option available to the Trump administration. Probably deferring the expiration tenure and stalling the continual ballistic missile testing would largely be taken into consideration. Nonetheless, no P5+1 member other than the US is willing to re-negotiate the deal. The Iranians have out-and-out rejected re-negotiating the deal on President Trump’s lines and their stance is supported whole-heartedly by Russia and China. As regards the UK, France and Germany, they may agree to the revision of this deal as per the demands of President Trump but neither they would compel or pressurize Iran directly for doing so nor align themselves with the shrill rhetoric of President Trump against Iran. So the US will have to unilaterally exert pressure on Iran, for re-negotiations, by imposing new sanctions under non-nuclear reasons i.e. Iran’s support to non-state actors in Syria and Yemen; ballistic missile testing; human rights abuses etc. The nature of sanctions is going to play a decisive role in determining the fate of the nuclear deal in this case. If Iran judges the new sanctions as old wine in new bottle, i.e. pre-JCPOA sanctions under new label, then it will accuse the US of violating the JCPOA and may comply in lukewarm manner with the provisions of accord. Resultantly, the deal would be disrupted but in favor of Iran as the five other states would have sympathy for Iran. In both the cases, the outcome will be the demise of JCPOA but in conditions favorable to Iran

3. Continuing with the deal

Continuing with the deal seems the best possible option which is based on two inter-dependable factors: Iran’s compliance with the agreement and sanction waivers at stipulated time by the US president under the JCPOA. Compliance ensues sanction waivers and vice versa. At present the IAEA has reported full compliance of JCPOA by Iran so no other factor must get margin for rupturing the deal. President Trump’s ultimatum to the Congress for addressing his demands is set to expire on May 12—the date of certifying the new sanction waivers. The US president must allow a frictionless path to this nuclear deal against his high-handed desires and meaningless apprehensions which could be resolved in diplomatic manner too. This will be the best course of action agreed upon by all the parties involved in negotiations and preparation of accord. Expiration of tenure and immediate inspection of all sites, at this stage, are not worth-negotiating; however President Trump could refer the provocative missile testing by Iran to P5+1 for ferreting out a diplomatic solution. It’s highly unlikely that JCPOA-like accord would be concluded by Iran on missile testing but a pause can be pressed on further missile testing. Nonetheless the future of ballistic missile issue with Iran amply depends upon the Missile Defense Review (MDR) to be released by the US government in May 2018. The Obama era’s European Phase Adaptive Approach (EPAA) aimed at installation of missile defense shields in Europe, in multiple phases, in the wake of nuclear and ballistic missile threats from Iran should be revised significantly in line with Iran’s adaptations after the implementation of JCPOA. Otherwise the chances of diplomatic settlement of missile issue with Iran would die down.

Conclusion— JCPOA facing a bumpy ride on brittle track

It is widely believed that the break out time for possession of nuclear weapon by Iran is one year this means in the absence of JCPOA limitations Iran requires 12 months for the preparation of enough fissile material to detonate a nuclear weapon. The break out time is not the achievement of JCPOA, rather a 15-year hiatus between the implementation date and start of break out time. President Trump’s postulates are based on his self-presumed hypothesis “Iran will ineluctably follow the path to producing a nuclear weapon soon after expiry of JCPOA restrictions.” But as explained in the previous sections that absent the technological advancements in the nuclear infrastructure, Iran would be lagging far behind after the year 2030 and at that time it would be very difficult for the Iranian government to surrender its well-heeled status in lieu of sanctions if its civilian nuclear needs were fulfilled.

It goes without saying that JCPOA is a magnum opus in the field of nuclear non-proliferation racked up during President Obama’s eight-year tenure. Its ripe fruits are not only enjoyed by Iran but the entire world as keeping Iran at bay from possession of nuclear weapon is one of the biggest contributions towards the non-proliferation regime. Questioning the existing nuclear infrastructure in Iran does not carry conviction: Two of the US’s closest allies Japan and South Korea retain nuclear hedging and nuclear latency respectively, despite an assured extended deterrence by the US, and their break out time is too lower than that of Iran. Japan is even believed to possess an advanced and robust spent fuel reprocessing system. At this critical juncture, President Donald Trump, being an ardent opponent of the Iran deal, has been surrounded by intractable and belligerent advisors who are cynical about the outcome of the nuclear deal with Iran besides advocating vociferously for military attacks on Iran. Similarly his closest allies in the Middle East are no different and are as hard as the nether millstone when it comes to dealing matters diplomatically with Iran. Keeping in view the foregoing factors and discussed parameters the JCPOA, an indubitable piece de resistance, is skating on a thin ice and grapples for its survival. The momentous nuclear accord may hardly get a glabrous go ahead during the Trump administration.