Abstract

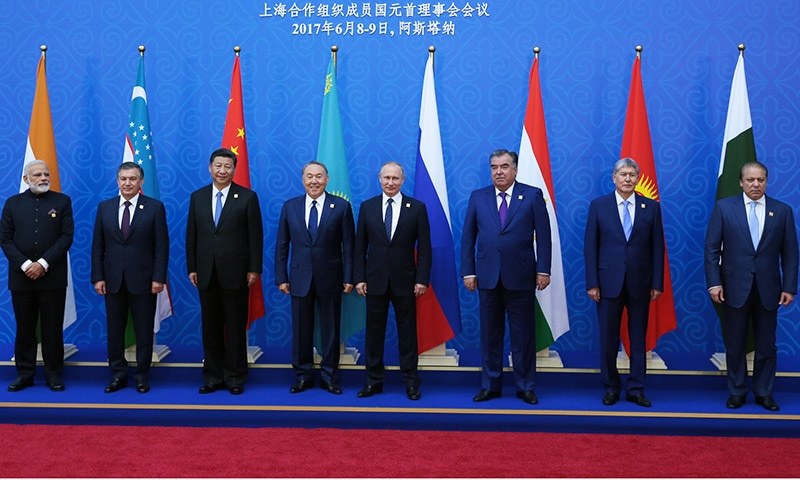

The International Code of Conduct for Information Security (ICCIS) is an international effort to develop norms of behaviour in the digital space, submitted to the UN General Assembly in 2011 and in revised form in 2015 by member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). According to its sponsors, the Code is intended to push forward the international debate on international norms on information security, and help forge an early consensus on this issue. With its connections to the SCO, the Code raises significant concerns over ambitious but ambiguous poster of international actors especially the Western powers towards their clandestine behavior in the sphere of digital space. The SCO states have been successful in building consensus around the Code given the ‘post-Snowden’ and ‘Arab Spring’ international political environment. Moreover, the SCO states confidently view the Code as a vehicle to redefine notions of sovereignty and territorial integrity to the digital space. Terrorism, extremism, separatism, and information security are posing fundamental challenges to sovereignty and territorial integrity of nation states. Some of the dominant states that exercise not only political, diplomatic, economic and military power over weak states to bulldoze their will are now very much capable of exploiting the digital space to shake the very stable foundations of sovereignty and territorial integrity. The close outlook of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security maintains a balance view towards safety and security for all. Due to its origin from the SCO member states, the Code already exists as a parallel binding agreement within Shanghai Cooperation Organization. All the new member states joining SCO will have to endorse and implement the SCO agreement on Information Security. Pakistan and India as new members will not be exception to it.

Introduction

According to International Telecommunication Union (ITU), more than 3 billion people are now using the Internet. With over 3 billion people using the Internet or nearly 40% of the world’s population, Information Security has become an international focus in this new age of computing.1 The Norton Cybercrime Report (2017) states that, “978 million people in 20 countries were affected by cybercrime in 2017.”2 Today, cybercrime rates are on the rise and almost every government in the world is affected by it. People are now, more than ever, falling victim to new forms of cybercrime, such as crimes found on social networking sites or mobile devices. As a result, consumers who were victims of cybercrime globally lost $172 billion an average of $142 per victim.3 Interestingly, this aspect of cybercrime is less expensive when it is compared to crime in cyber space, which is purely a domain of powerful States.

Many countries still are unaware of the future and without sufficient understanding have little idea regarding the threats of cyber space. The United States and the European Union have already mechanized information security, which many countries still lack. In countries without any awareness or security guidelines, vulnerability of cyber space would affect the very sovereignty and future of their nations.

According to France Diplomate, “new destructive practices are developing in cyber space, including criminal use of the Internet (cyber crime), including for terrorist purposes; large-scale propagation of false information, espionage for political or economic ends, and attacks on critical infrastructure (transport, energy, communication, etc.) for the purposes of sabotage”.4 The emerging dynamics of cyber security has opened not only new avenues of war but also policy dialogues to counter complex challenges associated with the threat.

Cyber Power and International Competition

Cyber power is a foundation of international competition and incorporates such elements as technology, personnel, economy, military and culture. The revelations by the whistle-blower Edward Snowden have offered the world a glimpse of the leading edge of the United States’ cyber power. The cyberattacks on Estonia, Georgia and Ukraine, widely reported by Western media, might be traces of Russian cyber power. Now, four of the world’s top 10 internet companies, Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu and JD come from China which might highlight the power of China’s internet economy. However, cyber power, just like national power, has also been in flux. In recent years, many countries have increased their investment in order to participate in the fierce cyber competition, even the United States, which enjoys extraordinary advantages in cyber power, is no exception. Japan, Australia and other countries are also making great endeavors to build their cyber capacities. Of course, for less developed countries, internet development and narrowing the digital gap remain their top priority.

Cyber Sovereignty vs. Cyber Freedom

In recent years, conflicts and stability of cyberspace have become an increasingly major concern to many countries who treat cyberspace as a strategic domain and have strengthened their cyber defense and offense capabilities. Cyberspace has been regarded as the “fifth domain” of equal strategic importance as the land, sea, air and space.5 This has intensified international competition in the field. As a result, cyber relations are becoming a new dimension for competition among great powers.

Countries such as China and Russia unequivocally support the principle of cyber sovereignty, while Western countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom vigorously advocate the idea of cyber freedom. The United States has attached great importance to forwarding its diplomatic messages with various information platforms, among which social media has become a new tool of American diplomacy. Although the US expects to occupy the international moral high ground through cyber diplomacy, many developing countries fear that freedom in cyberspace is just another pretext for the West to meddle in their internal affairs and violate their sovereignty, and worry that the West is seeking to engage in “color revolutions” through cyber means so as to undermine their national security, stability and development.

Cyber sovereignty is a natural extension of national sovereignty in cyberspace. After years of continuous negotiations, especially the persistent efforts of the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts (UNGGE) on information security, the principle of cyber sovereignty has been recognized by such international organizations as the United Nations and NATO6 and countries such as the United States,7 thus laying the foundation for future global internet governance and cyber strategic stability. However, the meaning of cyber sovereignty is still disputed. Of course, both cyber freedom and cyber sovereignty are relative in their significance and cannot be pushed to the extreme, otherwise these abstract principles may become a hindrance for a country’s internet development. For example, the European Union attaches much importance to such values as human rights, democracy and privacy in its cyber policy that its internet development lags far behind that of the United States.

Multi-lateral Approach vs Multi-stakeholder Approach

With regard to internet governance, countries such as China and Russia support the multilateral approach with governments taking a leading role, while the United States and other Western countries advocate a multi-stakeholder approach in which multiple actors participate, thus diluting the role of governments. The latter maintains that internet governance should take a bottom-up approach, in which actors like technical communities, individuals, and internet companies play a leading role, while governments are only one of the stakeholders.

In contrast, the multilateral approach is more in line with the national conditions of China, Russia and developing countries whose primary task is to strive for IT development. In this process, there is no doubt that their governments play a greater role in planning, guiding and coordinating the development of cyberspace. Along with the rapid expansion of the internet and the gradual growth of technological capabilities, it has become a strategic necessity for the participation of multiple actors in internet governance, as the government alone is not able to achieve effective cyber security. In its International Strategy of Cooperation on Cyberspace, released on March 1, 2017, China states that:

China calls for enhanced communication and cooperation among all stakeholders including governments, international organizations, Internet companies, technological communities, non-governmental institutions and citizens. Relevant efforts should reflect broad participation, sound management and democratic decision-making, with all stakeholders contributing in their share based on their capacity and governments taking the leading in Internet governance particularly public policies and security.8

Thus, both the multilateral approach and the multi-stakeholder approach constitute an integral part of any internet governance model.

Cyberspace Militarization

The existence of a cyber war is still controversial in theory, but there is no doubt that in practice ICT can be used for war. In recent years, the militarization of cyberspace has become more and more prominent, which is reflected in the flourishing ideas and theories on cyber war, the growth of cyber forces, and the research and development of cyber weapons, thus adding a new area of competition among nation states.

In the mid-1990s, the RAND Corporation put forward the idea of “strategic information warfare”9 and held that a “cyber war is coming.”10 Over a decade later, William J. Lynn III, then US. Deputy Secretary of Defense, wrote, “as a doctrinal matter, the Pentagon has formally recognized cyberspace as a new domain of warfare. Although cyberspace is a man-made domain, it has become just as critical to military operations as the land, sea, air, and space.”11 In December 2012, then US Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said that the US Department of Defense had drafted new rules of engagement in cyberspace, which would enable the US military to respond more quickly to cyber threats.

Russia has also conducted extensive theoretical research on cyber warfare from an early stage. The Information Security Doctrine of the Russian Federation, adopted by Russian Information Security Committee in 2002, listed cyber war as a sixth-generation war and charted the course for the development of Russian cyber forces. In short, Russia has attached great importance to cyber war, in particular the command of the information and electromagnetic domain. At its Warsaw Summit in July 2016, NATO recognized cyberspace as a “domain of operations” in which it would defend itself as it does in the air, on land, and at sea, and would focus on improving the cyber capabilities of its member states.12

Many countries have begun to build their cyber forces and related structures in an attempt to seize the initiative in cyber offense and defense. In June 2009, the United States set up a Cyber Command subordinate to the Strategic Command, conferring the new mission on its military of seeking dominance in cyberspace. On August 18, 2017, the United States elevated its Cyber Command to the status of Unified Combatant Command focused on cyberspace operations, whose head would report directly to the Secretary of Defense.13 A US Cyber Command news release said, “All 133 of the US Cyber Command’s Cyber Mission Force teams achieved initial operating capability as of October 12, 2016.”14 The Russian armed forces have also established “information forces” that are responsible for offense and defense in information warfare, with a view to ensure an advantageous position in information confrontation. The United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan, India and other countries have also set up their own cyber forces.

Countries have also been increasing their investment in the R&D of cyber weapons. The United States is well ahead of the rest of the world in this regard. In 2008, the Pentagon spent $30 billion building the National Cyber Range comparable to the Manhattan Project. In 2012, the Pentagon’s budget for cyber security and information technology reached $3.4 billion. The Pentagon has also developed a list of cyber weapons and cyber tools, whose use is broken into three tiers: global, regional and area of hostility, thus providing a foundation for waging cyber warfare in the future.15 Moreover, countries are also making great efforts to train their cyber forces. In short, despite the absence of a cyber war that leads to large-scale human casualties, countries are now scrambling to prepare for cyber warfare, and cyberspace is being increasingly militarized and weaponized. In other words, a cyber arms race has quietly begun.

Way Forward for Pakistan and the Information Security

In June 2017 Pakistan joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).16 Being a responsible SCO State means complying with all obligations taken within the framework of the Organization. Nonetheless, Pakistan has just started implementing all the relevant agreements which include almost 30 different protocols. One of the most important SCO documents is the intergovernmental agreement on cooperation in the field of International Information Security, which is also an effective instrument on combating cyber-crime.17 There are two competing models for ensuring IIS: one being imposed by the US and the other is set out in the aforementioned SCO agreement (which Pakistan is supposed to follow since we became full-fledged member of this prominent Organization).

The White House and its allies have unleashed a kind of an arms race in cyber space, building up its capabilities for affecting the critically important infrastructure of other States with sovereign foreign policy. In August 2017 Donald J. Trump increased powers of national cyber-command on conducting offensive operations abroad.18 Moreover, decisions adopted at the NATO summit in Warsaw in 2016 clearly show that the Alliance still regards cyber space as the fourth theater of war, enhancing methods for cyber offense.19

It is in Pakistan’s interest to develop a national International Information Security strategy and to design effective means of its implementation. In this regard it is worth using the experience already accumulated by the SCO and increase cooperation in the sphere, which includes providing assistance to the States suffered from cyber-attacks.

The SCO platform and its mechanisms are unique. It gives the opportunity to resolve inter-state contradictions through dialogue. The efficiency of the SCO is based on the principle of respecting interests of all members. They try to avoid confronting each other through hasty accusations as the International Information Security topic is largely sensitive and the source of a cyber-attack is extremely difficult to trace. It is vital to focus on shaping a regional International Information Security structure based on the SCO documents. This structure will give Pakistan additional opportunities to protect its sovereignty, cultural and religious values.

The US and its allies continue to enlarge the scale of cyber-weapons used to destabilize Muslim countries, first of all by means of the so called ‘color revolutions’, like the Arab Spring in Libya.20 The inter-confessional differences, ethnic and sectarian faultiness, social problems, dependency on foreign technologies and investments are ideal explosives of the cyber weapons. We can also be a target for such attacks. In fact, Pakistan has been a target of such attacks with clear intensions to destabilize it. All elements of national power are the targets of cyber weapons that through organized campaigns work to achieve its ultimate goal. Keeping in view the irrational US accusations and denial regarding Pakistan’s contributions in the war on terror and continuous silence of the majority Western countries; it is obvious that all of them collectively are not interested in a developed, prosperous and stable Pakistan.

Pakistan’s strategic partnership with China is being considered as a menace in Washington, because it is a serious impediment for setting US hegemony in the region. By now our authorities regard control on cyber-activities as an effective and adequate way to solve the problem. But it is not enough as the enemies are doing much more to exploit the narrow and simplified vision of Pakistan regarding international informational security. Due to neutrality and progressive posture of the regionalism vested in Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Pakistan needs to broaden the outlook and start practical cooperation with those SCO Members that have a genuine and substantial experience in International Information Security China and Russia and can assist in setting out national strategy in this sphere.

The US and its allies refrain from imposing international legal limitations on the development of cyber-weapons. Moreover, the US seeks not only maintaining its leadership but also legalizing cyber space militarization. They continue attempts to persuade other countries including Pakistan to support Western approaches to International Information Security. These approaches are based on the argument that the existing legal international norms such as ‘the Budapest convention on cyber crimes, 2001’ shall be followed.21 In fact, this document provides a trans-boundary access to national computer data of the states. It is assumed that the US and its allies exploit this situation to conduct cyber offenses abroad. At the same time, the status-quo states are trying to distract attention of the international community from the initiatives promoted by SCO and internationalization of Internet. Washington is trying to impose its model of cyber security based on the multilateral approach towards governing the internet, with government playing secondary role. The Americans have in fact blocked the work of the UN governmental experts on International Information Security, which failed to agree upon its final document that included proposals by SCO states. Pakistan could strengthen its authority within SCO through more active promotion of SCO initiatives in different international structures in the field of International Information Security.

The first step in this direction could be joining as a cosponsor to the “International Information Security rules of conduct” that have been circulated within UN.22 Russians also have submitted a proposal on ‘Universal UN Convention on Countering Cybercrime’ that is acceptable alternative to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrimes. It is also important to maintain the UN leading role in all the International Information Security issues because of economic and social problems many countries face and therefore, do not pay enough attention to the risks of militarization of the cyber space. In this regards, Pakistan could spearhead the formation in the Muslim world that can put a permanent check on the faultiness and future risks like ‘Arab Spring’. The influential group of likeminded Muslim states opposing military conflicts in cyber space and supporting SCO initiatives would definitely be a strategic gain for Pakistan. To start with, organizations like OIC and the OECD can provide launching pad to execute the idea.

After Pakistan joined SCO, it should expect more active steps of Western special services inside Pakistani cyber domain to discredit SCO instruments on International Information Security. Pakistan should show more restraint in bilateral interaction with the US in this field, at the same time engaging deeply in SCO cooperation based on the above-mentioned International Information Security agreement. One of the potential avenues for collaboration is sharing data on the facts of external cyber-attacks on government-controlled servers and hubs. Such sharing is extremely useful for developing a coordinated SCO response to cyber threats.

Conclusion

Washington is seeking to make Islamabad more dependent on Western technologies, imposing on her the unbeneficial partnership in some sensitive areas for national security, including military technical cooperation. Meanwhile, Pakistan cannot exclude that the military equipment and systems sold by the US will contain hidden software transmitting data to the producers and, moreover, enabling them to control these equipment and systems. A good example is “STUXNET” virus used by the Americans in Iran.23 The Pakistani competent agencies should reconsider their cooperation with US on whether it complies with its national interests or denounces the very national sovereignty.

End Notes

1 International Telecommunication Union (ITU), “2015 ICT Figures,” available online at: http://www.itu.int/net/pressoffice/press_releases/2015/17.aspx#.WpbVeq6WbIV (accessed on January 27, 2018).

2 “Norton Cyber Security Insights Report 2017 Global Results,” available online at:https://www.symantec.com/content/dam/symantec/docs/about/2017-ncsir-global-results-en.pdf (accessed on January 28, 2018).

3 Ibid.

4 “France and Cyber Security,” available online at: https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/defence-security/cyber-security/ (accessed on January 25, 2018).

5 William J. Lynn III, “Defending a New Domain: The Pentagon’s Cyberstrategy,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 89, No.5, September/October 2010, p.101.

6 Michael N. Schmitt, ed., Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Warfare (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 65.

7 Harold HongjuKoh, “International Law in Cyberspace,” September 18, 2012, http://www.state.gov/s/l/releases/remarks/197924.htm (accessed on January 22, 2018)

8 “International Strategy of Cooperation on Cyberspace,” Xinhua, March 1, 2017, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2017-03/01/c_136094371.htm (accessed on January 22, 2018)

9 Roger C. Molander, et al., Strategic Information Warfare: A New Face of War (RAND, 1996).

10 John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, “Cyberwar is Coming!” in John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, eds., In Athena’s Camp: Preparing for Conflicts in the Information Age, RAND, 1997, pp.23-54.

11 William J. Lynn III, Ibid.

12 “Warsaw Summit Communiqué,” Press Release (2016) 100, July 9, 2016, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm?selectedLocale=en (accessed on January 22, 2018)

13 The White House, “Statement by President Donald J. Trump on the Elevation of Cyber Command,” August 18, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/08/18/statement-donald-j-trump-elevation-cyber-command; Munish Sharma, “US Ups the Ante in Cyberspace,” August 26, 2017, http://www.eurasiareview.com/26082017-us-ups-the-ante-in-cyberspace-analysis (accessed on January 22, 2018)

14 “Initial operating capability” means that all Cyber Mission Force units have reached a threshold level of initial operating capacity and can execute their fundamental mission. See Department of Defense, “All Cyber Mission Force Teams Achieve Initial Operating Capability,” October 24, 2016, https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/984663/all-cyber-mission-force-teams-achieve-initial-operating-capability (accessed on January 22, 2018).

15 Ellen Nakashima, “List of Cyber-Weapons Developed by Pentagon to Streamline Computer Warfare,” The Washington Post, May 31, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/list-of-cyber-weapons-developed-by-pentagon-to-streamline-computer-warfare/2011/05/31/AGSublFH_story.html?utm_term=.7fb8069678ec (accessed on January 22, 2018)

16 “It is a historic day’: Pakistan becomes full member of SCO at Astana summit,” Dawn (June 09, 2017). Available online at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1338471 (Accessed on January 26, 2018).

17 Sarah McKune, “An Analysis of the International Code of Conduct for Information Security,” The Citizen Lab (September 28, 2015), available online at: https://citizenlab.ca/2015/09/international-code-of-conduct/ (accessed on January 25, 2018)

18 Lolita C. Balder, “Trump approves plan to create independent cyber command,” PBS (August 18, 2017), available online at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/trump-approves-plan-create-independent-cyber-command (accessed on January 25, 2018)

19 “Warsaw Summit Communiqué: Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw 8-9 July 2016,” NATO (July 09, 2016), available online at: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm (accessed on January 24, 2018).

20 According to Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Russian military leaders view the color revolutions as a “new US and European approach to warfare that focuses on creating destabilizing revolutions in other states as a means of serving their security interests at low cost and with minimal casualties. For more details please see, Anthony Cordesman, “Russia and the “Color Revolution”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, (28 May 2014). Available online at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and- “color-revolution” (Accessed on January 25, 2018)

21 Council of Europe, “Convention on Cybercrimes,” available online at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/185 (accessed on January 23, 2018)

22 “Russia Presents Draft UN Convention on Fighting Cyber Crimes in Vienna,” Sputnik (May 25, 2017), available online at: https://sputniknews.com/science/201705251053959333-russia-un-convention-cybercrimes/ (accessed on January 25, 2018). Also see, “Statement by H.E. Mr. Sergey V. LAVROV, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, at the 72nd session of the UN General Assembly,” (September 21, 2017), available online at: https://gadebate.un.org/sites/default/files/gastatements/72/ru_en.pdf (accessed on January 23, 2018).

23 By Ellen Nakashima and Joby Warrick, “Stuxnet was work of U.S. and Israeli experts, officials say,” The Washington Post (June 2, 2012). Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/stuxnet-was-work-of-us-and-israeli-experts-officials-say/2012/06/01/gJQAlnEy6U_story.html?utm_term=.53ba6ae59bfa (accessed on January 28, 2018)