There are few larger-than-life figures in Pakistani history. Asghar Khan was one of them. He became a legend in his lifetime, a man who had not one but three careers.

First, the air force career which conferred on him the lifelong title of air marshal. Second, the political career in which he took on more than one authoritarian figure. And, third, the writing career in which he penned many critiques of strongly-held myths in Pakistani psychology, notably that military rule is better than civilian rule and that Pakistan is militarily a match for India.

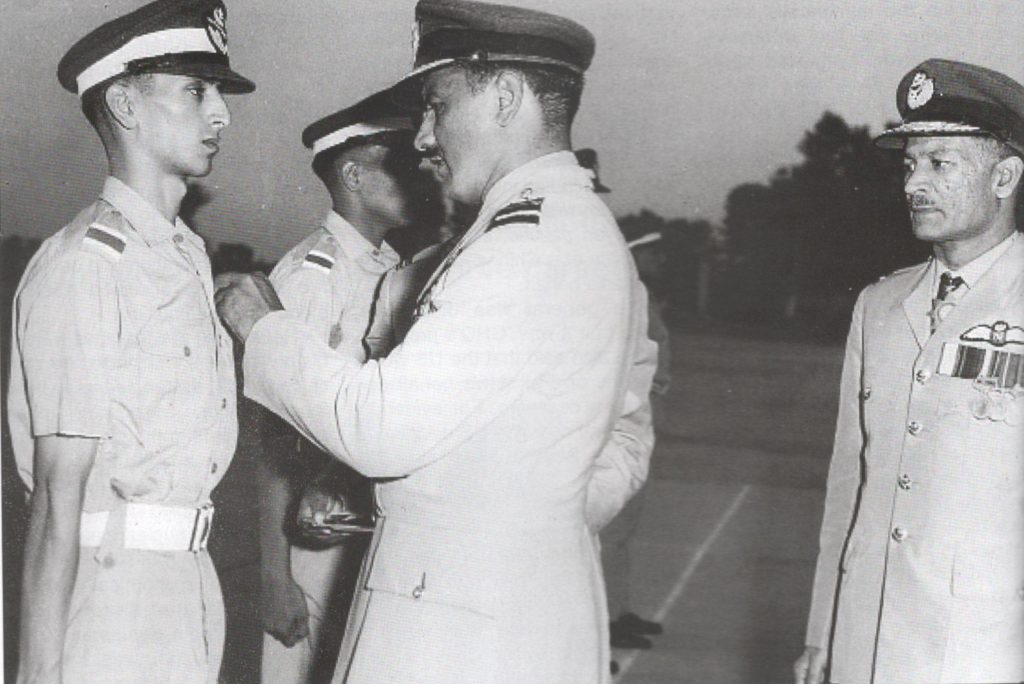

He was the first Pakistani to command the air force. During his tenure, which ranged from 1957 to 1965, modern jet aircraft were inducted into the air force, including F-86 Sabre fighter bombers, B-57 Canberra light bombers and F-104 Starfighter interceptors. The air force was honed into a fine fighting machine, possibly one of the best in Asia.

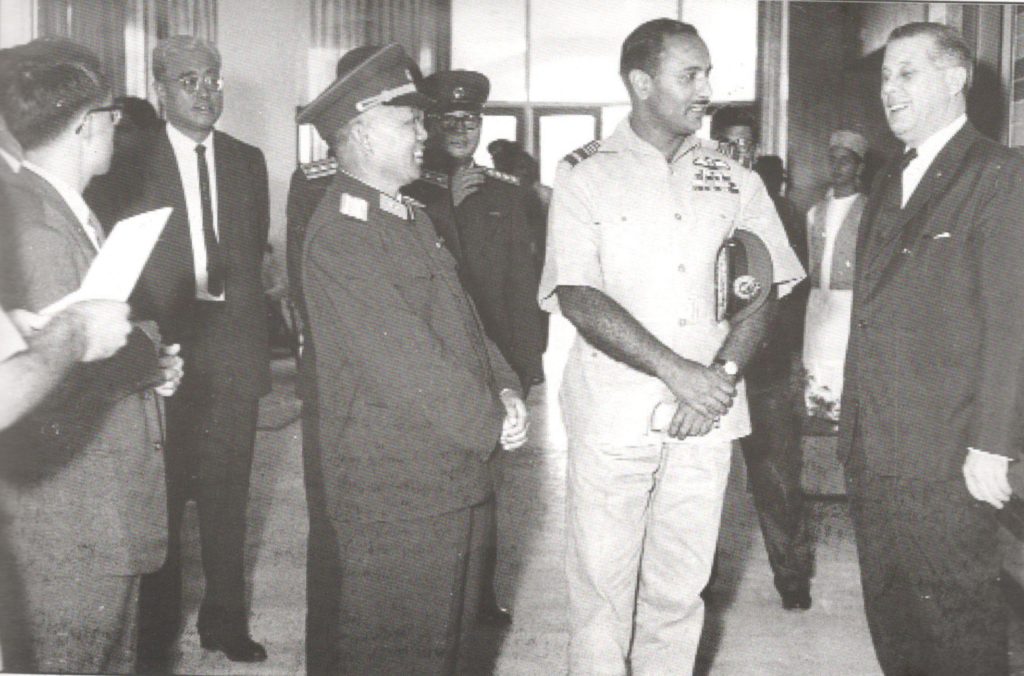

It was ready for the challenge when war against a much larger enemy was thrust on it by the Pakistani army’s ill-advised thrust into Kashmir in 1965. When war came, he had handed over the command of the air force to Air Marshal Nur Khan and taken over the management of PIA. On the fourth day of the war, he was sent as a special emissary by President Field Marshal Ayub to China.

In his first book, ‘The First Round’, he recounts the meeting with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. The latter offered generous military assistance to Pakistan. But Ayub did not want the arms to come directly from China because that might upset the Americans. Zhou was concerned that Pakistan would not be able to hold out long enough for the arms to arrive by any prolonged route. He wanted to meet Ayub in person to go over this matter, to determine his resolve to engage in a protracted war with India, and to suggest that the Pakistan army change its tactics to put the numerically larger Indian army on the defensive mode. However, Ayub was reluctant to have Zhou visit him in Pakistan, again for fear of upsetting the Americans.

Despite Ayub’s odd attitude, the Chinese provided the equipment Ayub desired through Indonesia. China also moved some of its forces toward India’s northern borders but they “had hardly arrived there when a ceasefire was ordered, and they had to say that they had come there with no aggressive intentions but to collect their cattle, which the Indians had taken away from Tibet.”

He says that all these developments “showed the non-serious manner in which we involved ourselves in a war with India in 1965… When we went to Tashkent in January 1966 we had no choice but to formalise an end to the war on India’s terms,” a war which had not only failed to wrest Kashmir from India but almost cost Pakistan the city of Lahore.

After Tashkent, Asghar Khan concluded that the field marshal had to go. He was approached by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto who had also fallen out with Ayub and who was in the process of creating the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). But after talking with Bhutto, he concluded that Bhutto was seeking power for its own sake. He concluded that Bhutto would prove to be even more dictatorial than Ayub if he came to power and decided to create his own party.

In 1971, civil war broke out in East Pakistan because of the army’s ill-advised decision to not transfer power to the Awami League that had won the general elections. He visited East Pakistan several times after military action had broken out. On being told by one of the generals that the Mukti-Bahini organisation was about to be eliminated, he warned that raised the odds of an Indian intervention, given that the snows would shut down the Himalayan passes, eliminating any possibility of a Chinese invasion on Pakistan’s behalf.

The general was dismissive, saying that it was ‘GHQ’s problem’, and he also said that the US would intervene on Pakistan’s behalf and institute a ceasefire. For evidence, the general cited the US decision to deploy the Seventh Fleet in the Bay of Bengal.

Asghar Khan notes that the when the Indians invaded East Pakistan, the general who had briefed him fled to Burma in a helicopter. As for the ceasefire, it did indeed come to pass. But it ‘was not brought about by the United States but imposed by India in a ceremony at Paltan Maidan which was the darkest day in our history’.

When Bhutto was installed in office, and he began to denigrate all other political figures, and began to have lesser opponents picked up and thrown into jail, or worse, Asghar Khan galvanised the nation’s leading opposing parties into the Pakistan National Alliance. Their rallies drew massive crowds and made Bhutto very nervous. With General Tikka at his behest, he was prepared to use arms to kill thousands to quell the opposition.

The elections were rigged, leading to nationwide protests. The ensuing political imbroglio was brought to an end by an army coup that deposed Bhutto. General Zia promised free elections in 90 days but never held them.

In 1999, General Pervez Musharraf attacked Indian positions in Kargil, Kashmir and claimed victory. Asghar Khan ridiculed the assertion. He asserted that Pakistan’s efforts to internationalise the issue had backfired. “The outcome was diametrically opposed to the campaign’s objective. All major powers, including our old ally China, told us to get back to the line of control.” An astute observer, he said that the high moral ground on which the struggle in occupied Kashmir stood had been sullied.

Reflecting on Pakistan’s long history of wars with India, he concluded that Pakistan seems to have fought all those wars for no apparent purpose other than to arrive at a cease-fire. He advised the nation to realise “that war is serious business, made more serious by the acquisition of a nuclear capability.”

He called on Pakistan’s leaders to build an ‘economically strong Pakistan with a prosperous population and stable democratic institutions … as that was the best guarantee for the survival of the country.’ This will also yield a bonus for Pakistan’s Kashmir policy since the urge of Kashmiris to join Pakistan ‘will gather strength if they see happiness and prosperity across the border’.

The air marshal was gifted with a long life. There can be little doubt his life will continue to inspire Pakistanis for generations to come. One hopes that it will also cause the army to rethink its Indo-centric national security strategy.

In his long life, the man who was an institution mentored many who will carry forward his mission. One of them, Air Commodore (Retd) Sajjad Haier, has penned a fine tribute.

Eventually, the air marshal’s legacy will endure through his writings. The book that sums it all up is his last work, “We’ve Learnt Nothing from History.”

Courtesy: Daily Times