Context

As the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia enters a new phase of political changes, questions are being raised about what it means for the region and beyond. The regional tussles between Iran and Saudi Arabia have already engulfed Yemen and Syria, and Lebanon is the recent causality.

As previously described in this space the peripheral regions of the Islamic world, which excludes the Arab world, are drifting into the influence of Russian and China and away from the western alignment. While Shiite Iran was already close to these emerging powers, the list now also includes NATO member, Turkey and major Non-NATO ally, Pakistan. The fate of Indonesia and Malaysia hangs in the balance, and the core regions represented by the Arab world, and Saudi Arabia seem to have aligning itself with the West for the time being.

The question becomes more important as these tussles mount between Russia, China and the US, how will they translate for the core and the peripheral regions of the Islamic world. More importantly, how will these competitions intersect with the local societal political balance and help us understand the future alignments.

World War l an ll present examples of how this is likely to play out. In World War l, the sick man of Europe, Turkey, had initially attempted to side with both the Central and Entente powers but ultimately sided with the Central powers. Muslims ended up fighting on both sides of the alliances, often with each other, depending on which colonial powers they were under. In both world wars, the various parties joined the alliances based on what the victory would represent for their respective interests.

Analysis

Liberal Elites and Client-State Structure

Subsequently, as the nation-state structure emerged from the ashes of world wars, the liberal order prevailed. The secular elements within the former colonies that had helped the colonialists in the wars and in the maintenance of their occupation, were naturally handed over the reigns of power as foreign powers departed.

This is in contrast to the conservative and religious segments within these societies which were usually leading and supporting the insurgencies against the colonial powers for independence, and had often sided with the adversarial global powers. In this context, while the colonial powers withdrew after being weakened under the weight of global power tussles, they maintained their influence over the newly emerged states.

As the Cold War got under way in earnest, the Client-State phenomenon emerged. There were a number of political, economic, and security mechanisms that helped to maintain the post world war client-state relationships. The liberal elites played a considerable political part towards this end for the nations allied with the West. This was in contrast to the methodology adopted by the Soviet Union which was close to the socialist segments.

After gaining independence, the fragile former western colonies faced a two-fold threat. On the external side they needed to confront the Soviet bloc represented by the Warsaw Pact nations, which came in to being in 1955. On the internal front, they had to counter elements that were often against the liberal order. Thus they needed economic and military support to survive politically and remain credible.

Many of the new regimes were rewarded with military and economic assistance for their allegiance. This developed into a dynamics where the leaders of these states, which were often undemocratically elected, paid scant attention to the needs of their citizens. Instead they required the support of foreign powers to stay in power rather than the consent of its populace. Obviously, this resulted in corrupt regimes and large military budgets. Because of these vulnerabilities and dependencies, the leaders of such nations were easily exploitable. Whenever they drifted from the script, mutinies and revolts were not far away.

Such policies also existed prior to and during the world wars and continued afterwards. The client states had to serve the interests of foreign powers and generally could not develop independent foreign and economic policies. Consider for example the Amau Doctrine to display the dynamics that was playing out in the Pacific and Latin America.

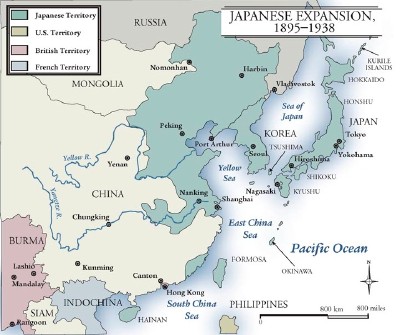

Through the Amau Doctrine, formulated around 1934, Japan declared that China does not have the right to seek foreign assistance or to resist Japan in establishing a new order under the aegis of an East Asian League. Furthermore, any third parties involved in China would have to consult Japan. Historians believe that between 1933 and 1937 two events occurred that made Japan nervous: first, the increased Soviet presence on the Manchukuoan frontier and second, the formation, in 1936, of an anti-Japanese alliance consisting of Chinese Nationalists and Communists, enjoying Soviet support.

The Amau Doctrine was the Japanese equivalent of America’s Monroe Doctrine (1823), which was designed to protect American interests in the Western Hemisphere. The premise of Amau is that Japan reserves the right to act unilaterally in order “to preserve peace and order in East Asia.”

The context was the depression of the 30s, when Japan lost a substantial amount of its trade as a result of international trade barriers. The Doctrine was chiefly intended to convert the then feeble China into a client state and to establish Japan as the dominant power in the Pacific while containing Russia, resurgent then as now. For Japan, China was the main source of raw materials, as well as possessing tremendous strategic importance in its struggle with Russia.

Afghanistan provides another example. Through the treaty of Gandomak reached in 1879, Britain gained full control of Afghan foreign policy from the king of Afghanistan.

Post Cold War Order, Power Realignment, and Local Power Centers

The Cold War ended with the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 and a period of Unipolar world emerged where the US reigned as the sole superpower. However, that phase has been followed by a world order marked by Multipolarity and depicted by BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa).

As the tussles of the emerging and established powers heats up, and with global power realignment in full swing, the traditional liberal power structures in the so-called client states are in flux too, and they are finding harder and harder to deliver.

The campaign against extremism has also significantly altered the traditional inter-institutional power structures. The direct causality of the war against terror has been the shrinking space for the liberals in the Islamic world, and the steady rise of the conservatives and the religious conservatives. Obviously, the natural political alliance that would emerge from this changed ecosystem is between the nationalists and the conservatives of different colors.

Moreover, while the role of liberal elites was questionable in the post World War order, the function of military establishment became the key as the arbiter of the societal balance. In Turkey, Egypt and Pakistan, the military establishment has helped in sustaining the liberal order.

Moreover, the cordial relations of the liberals with the West have also facilitated the nationalistic agenda of the military establishments. This is now changing under the realignment triggered by the Multipolar world. The liberal power structures have outlived their utility for the military establishment as well, and their credibility is too fragile and exposed to deliver for the West either.

To their advantage, both China and Russia are building their ties with the nationalists and the conservatives as the new power bearers of societal power. After all, in reaction to the Unipolar world, they have also adopted policies that support nationalistic agendas such as respect for national sovereignty and non-interference in the affairs of other states, while using UN as the primary platform to resolve crises.

How the liberals in the Islamic world adopt to the changing scene will be interesting. Will they act as spoilers or move themselves to the new Center is yet to be seen. Irrespective, going forward resisting or not recognizing the changed atmosphere will be risky for the West. It could lead to local unrest, civil wars, military coups, or hardliners taking over the helm of power.