Introduction

1. For many years after independence in 1947, the street slogan in India was that Hindus and Chinese are brothers1. Later, there was the 5-point agenda, the Panj Sheel, forwarded by the Indian leadership regarding peaceful coexistence and maintenance of cordial relations with China2. However, in the winter of 1962, following strained diplomatic and military relations, India and China went to war in the contested Himalayan region over border demarcation issues. The seeds of this conflict were laid long before i.e. during the British colonial rule when various borders of India were demarcated under a different set of conditions. While there is a long history of contentious pre-partition demarcations3, this particular conflict pertains to two distinct areas in the northern mountainous regions where India shares a border with China. Located on arid lands with extreme weather conditions and an average altitude of 14,000 feet, the British-Indian government had previously made several attempts to resolve these issues. However, in the Indian pre-partition era, the geostrategic situation of the late 19th to early 20th Century had a different context. The primary concern at that time was that the jewel of the British crown – India – an important provider of imperial wealth, commodities and military manpower was to be safeguarded from the north by a growing threat of possible Russian expansion4. Creation of buffer zones was thus one of the prime factors in British demarcations and boundary settlements. At some places, tradition and understanding was given precedence over exactness5. Decades later, these incomplete or dual interpretable demarcations were to haunt their native inhabitants.

2. After independence in the post WW 2 era; the context of boundary demarcations quickly transformed for India and then China as she transformed into the Peoples Republic of China or PRC in 1949. Consequently, each claimed rights to their traditional sovereign territorial lands. In part, misunderstandings and misinterpretations followed by political mishandling of the situation caused these two6, who once enjoyed cordial relations and were in constant diplomatic communication, to finally draw battle lines and go to war. Clausewitz thus wrote more than 100 years ago, ‘it is clear that war is not a mere act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political activity by other means’7. What exactly happened from 1947 to 1962 is not just another war story of military history. It laid down the context of the future security matrix for the South Asian region and beyond. Today, this region has the two most rapidly rising economic and military powers of the 21st Century and is home to more than 2.5 billion people. While this conflict concerns two protagonists, as a consequence, few major and secondary effects were generated on other regional and global players that are valid till date.

3. As of today, the 1962 Indo-China war stands as a frozen conflict8; what can be drawn from this war in terms of regional stability? The answer to this question is not simple as it is a live and evolving situation. Then, due to the continuing applicability of its causes, it would be necessary to briefly narrate history of the problem, conditions leading up to the conflict and its outcome. This article will analyze the problem in its entirety following the single case study methodology, then it will evaluate its impact on future relations between the two opponents in particular and other ‘concerned’ regional countries, specifically Pakistan. While undertaking this analysis, it would be evident that from 1962 onwards, the two nations view each other with caution, with momentary periods of border conflicts and rising tensions in an irregular sinusoidal sequence9. Consequently, the main structure of external security for the two, at least in the South Asian region and specifically for the Indian defence policy has clearly transformed. It would be clear as to why continued development of Indian military potential10, including its nuclear, space and guided missile programs11 and efforts to acquire blue water naval capabilities12 clearly link with her foreign policy. This in turn is based on Indian relations with Pakistan, her conflicting interests with China and her desire to attain great power status. Hence, the Indian politico-military psyche, despite the Bollywood stance and other soft image initiatives is set at a threshold defined by the strong requirement to retain overall balance with a rising China13.

4. However, in this article, due to the vastness of the subject, multiple issues like details of Indian rivalry with Pakistan and other Chinese disputes in the South or East China Sea’s would be briefly mentioned, only to provide an overview of the wider canvas of the future context of South Asian geostrategic concerns. Today, beyond the dawn of the 21st Century and hyper-connectivity of the globalized world, opportunities have revitalized intentions of China and India to sustain high economic growth. Even as there is realization that economic cooperation would be mutually beneficial, there is an additional factor i.e. competition for attaining or retaining strategic leadership – at least in the South Asian region. While both India and China are well placed on the path of improving diplomatic and economic relations, the factor of ‘keeping an eye on each other’ with transient periods of tensions continue to exist till date. Needless to emphasize, another military conflict between these now two nuclear powers could easily translate to adverse global effects. Subsequently highlighted arguments explain their relations and reasons. As a final point, we will also highlight the consequent impact of 1962 Indo-Chinese war on global strategic bloc alignments and their readjustments that would affect global stability in the 21st Century. In conclusion, we would synthesize the main factors considered and attempt to rationally answer whether there is possibility of reemerging tensions or improved relations between the India and China.

Historical Perspective of the Problem

5. The border war of 1962 with the ensuing rivalry and strategic competition between India and China is not limited to one incident. While the 1962 border war is the main event, there are a series of short skirmishes before and much later. As in many other cases, China is usually considered and portrayed as the aggressor – the Asian tiger that initiated this conflict as well14 – supposedly initiated as a part of traditional and ancient Chinese grand strategy to secure its near abroad or peripheral regions. However, Neville Maxwell, amongst others, in his epic work, ‘India’s China War’ has carried out in depth research and traces the background of this conflict. As the conflict stands unresolved till date, a short lesson in the context of geographical orientation is thus necessary.

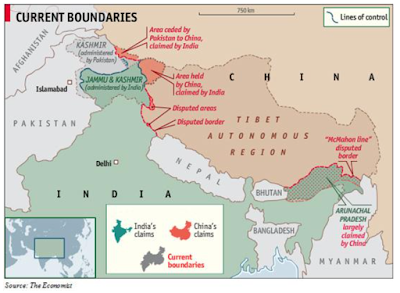

6. To this day, the conflict involves two separate areas on the approximately 4000 Km northern border of India with China. First is the North Eastern Frontier Agency or NEFA, a province of India, now called Arunachal Pardesh that borders with Bhutan (see map). The northern boundary of this area is the disputed and infamous McMahon Line15, used by the British to demarcate and separate China’s current autonomous Tibet region. This line was drawn after a formal treaty with the then independent Tibetan government in 1914 through another Simla agreement16. The line was contested after independence and an independent Indian survey after 1947 did find some inconsistencies. However, Maxwell and others have has gone into great length to explain the problem in its interpretation by the Indians17. This was primarily due to the traditional Indian comprehension and folklore that the summits of the Himalayan range separate India and China rather than other demarcated boundaries. While there are other minor inconsistencies in the actual border pillars marked in the pre-partition era by the British Army, these issues strongly came to limelight when India started publishing her own maps of this region in 1954. The actual McMahon line therefore exists South of Indian interpretations. The other contentious point for the Chinese till this date is the town of Tawang under Indian control and remains as one of the potential flash points of the future18.

7. The second area is more than 1000 Km to the west of NEFA and is called Aksai Chin19. Both China and India lay claim to this land but once again Maxwell along with other sources explains at length, problems of Indian interpretations. In essence, this issue goes further back to the 1840s when independent Sikh regiments i.e. of Indian princely states had conquered this area. But these were evicted by the Chinese counterstroke and pushed back further down till present day Ladakh in India. The two fighting forces finally disengaged and a non-interference treaty was signed in 1842. Each force i.e. the Chinese and the Sikh regiments had a reason to disengage. The Chinese were involved in their first Opium war while British India was getting destabilized as it drew near the Anglo-Sikh tensions before the first war of independence or the mutiny of 1857. To the Chinese therefore Aksai Chin was their land as always20. In this case, the McDonald – McCartney line i.e. the 1865 British survey expedition to demarcate this area from China was acceptable to the Chinese. India realized this only after Tibet was annexed by China in 1950 and a road was being subsequently built by them through this area from 1956-67.

The 1962 Border War

8. At the core, it was not the demarcation or rejection of these lines that led to war. The problem lay in handling of the situation in which Indian domestic political bickering and an extreme hard line stance adopted by the Indian government under Indian PM Nehru21. Initially after 1947, there were steadily growing relations between India and China. India was the 16th Country to recognize China and was a mediator and facilitator from the Chinese side in the resolution of the Korean conflict of the 1950s22. But as the years passed and when problems of border demarcations came to light, there was no clear perusal of diplomatic claims or strategy to peacefully resolve the issue. The exception, (as of today) was the media fire and parliamentary rhetoric in India. Clarifications were not directly sought despite Chinese non-recognition of Indian maps printed in 195423 (which are since then taken as reference, specifically by the western countries). Diplomatic miscommunication or inadequate communication or a combination of both soon led to a short skirmish in 1959 between Indian border patrols beyond their territory in NEFA i.e. the McMahon line while confronting Chinese frontier guards. Another skirmish occurred two months later in Aksai Chin24. In response, the Chinese strengthened their positions north of NEFA and initiated diplomatic efforts while consolidating their positions in Aksai Chin. But even then, initial Chinese military re-deployments went largely unnoticed.

9. After the first skirmishes, Indian domestic portrayal of the situation was understandably of Chinese aggression. In the post Korean war era and height of the cold war, this view was largely accepted by the west in support of a democratic India rather than a communist China25. Strangely, while diplomatic communications continued, the skirmishes soon went into the background due to other domestic commitments in both countries. When the topic did revive, it arose strongly in Indian parliamentary debates. Hence the Indian government came with a plan to resolve the issue – once and for all!

10. What followed subsequently actually aggravated the situation as India adopted an aggressive stance that was subtly called its forward policy26. This was to militarily evict the aggressors from perceived Indian claimed territory with no further discussions unless complete and unconditional Chinese withdrawal. The stance in itself was the perfect ingredient for a military conflict. Therefore, despite repeated Chinese requests, visits by PM Chou En Lai27 and numerous other diplomatic efforts, the Indian stance grew harder. Peace initiatives by other countries like Sri Lanka were also fruitless (note the similarities even with today). Contrary to the facts and against strategic appreciation by the Indian army, the Indian political leadership domestically portrayed India to be militarily in a stronger position with better preparations. Moreover, it was the assessment of the political leadership (that was largely uncontested by the Indian army’s hierarchy) that China would not militarily respond to aggressive Indian patrols – a critically incorrect military and strategic assessment that caused neither the government nor military leadership to adequately prepare for a Chinese response. This posture was in fact converse to the Indian army field commanders’ views from the Himalayas28.

11. Consequently, as the media and public debates on military skirmishes grew intense, soon it was a matter of internal drive by the population and political opponents to the ruling Indian leadership to militarily evict the Chinese29. Therefore, during October – November 1962, Indian army forward patrols on encountering and engaging Chinese frontier guards initiated the spark for the border conflict30. After a brief lull in the fighting, what followed next was the systematic defeat of ill prepared but numerically equivalent strength of Indian troops31. By the time the Indian political leadership and military hierarchy did accept the real ground situation and began emergency deployments with logistic moves, it was too little too late32. Despite all efforts, the conflict concluded with a humiliating defeat for India. As often, strategic miscommunication, operational misinformation and incorrect strategic appreciations do cause such results.

12. After achieving their objectives, the Chinese ground forces unilaterally declared ceasefire and withdrew to the pre-war positions. The Chinese leadership simultaneously exhorted the Indians to diplomatically resolve the issue while returning all Indian captured weapons and ammunition. Interestingly, there was no use of airpower by either side other than pre-war logistics drops and reconnaissance flights with the Indians continuously fearing repercussions of Chinese air force retaliation. There was no role for either navy in this war either and no assets were ever deployed. While there were numerous political and military errors at the strategic and operational levels, this was a scar on the Indian political leadership, military hierarchy and the public that was not to go away easily. In essence, what the Chinese had adopted was a strategy that was militarily applied on them by the Russians previously33.

13. Through the years after 1962, no progress on any of the issues could be made specifically until the death of PM Nehru in 1964. Moreover, it was only later when public pressure into answers following tensions with Pakistan that the Indian government initiated an inquiry and began to look into the real reasons of the conflict and its outcome34. The official results of the war in terms of casualties were published by India in 1965. Diplomatic relations between the two actually never revived until 15 years later35. Between these years, there were a series of events and two more near engagements until one more recently that highlight the reality of the issue. However, other than these military centric events, there have been a series of political, diplomatic and economic aspects of this conflict that are essential to contemplate.

Indo-China Diplomatic and Economic Relations: Post 1962

14. Barring occasional statements to denounce each other, there were no diplomatic relations between the two states until the end-1970s. During this time period, the Indian stance remained unchanged from the legacy of Nehru and the Chinese retained their stance for diplomatically resolving the issue while maintaining forces at the pre-1962 war positions – a stance not followed in totality by India36. However, after elections in 1977, Indira Gandhi’s political party (the daughter of Nehru) lost the elections and power was transferred to a new leadership and political party in India. Thus, efforts for reviving diplomatic relations were reinitiated at the end of 1978 when the Indian Minister for External Affairs visited China37. The build-up of relations was painfully slow as there were various tensions and military events in parallel (explained later) that would stall the process. Nevertheless, through the 1980s there were reciprocal visits by the Chinese and diplomacy also prevailed in thwarting military buildup in the north during the mid 1980s. Nevertheless, after the end of the Cold War, the context of relations between the two started to change. The 1990s again witnessed reciprocal visits between the heads of states of the two states and border dispute resolution mechanisms were put in place. Occasional reminders by the Indian leadership that China remains its prime enemy continued, such as after the Indian nuclear tests of 1998. The development of Indian long range ballistic missiles to reach major Chinese cities and other military capability enhancement measures were also in the same context. These developments involving billions of US $ in an otherwise third world state clearly indicate that despite steady improvements in relations, the 1962 conflict has played a major role in the instability of the region.

15. By the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, globalization and 21st century international system of free markets, commerce and trade diversities were in the prime interest of both states. Both were raising economies. Therefore, to reduce tensions, the 2000s marked further improvements in diplomatic relations38. Although tensions did not totally cease, mutual visits by high level delegations and heads of states continued. By now, it was evident that track-2 diplomacy and Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) needed to go beyond cultural visits and be accompanied with inter-state trade to improve relations. Thus by 2004, the Indo-China trade had crossed US $ 10 Billion mark with steady increase.39 Occasional political disputes, for example on China’s membership in the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and China’s opposition to Indian permanent membership to UNSC and NSG continue40. However, alongside these mutual diplomatic, political and economic measures to improve relations, there is a gray shade to this relationship that needs to be taken into perspective to acquire a 360 degrees view of their mutual relations.

Post 1962 Military Events

16. Contrary to common understanding, there is more than one event in the Indo-China conflict. Excluding the 1962 war, there are six major events between the two states over recognition of borders till date. Commencing in September and October of 1967 there were two separate incidents involving exchange of fire on the northern border between India and China with casualties on both sides41. This time, the area was close to Sikkim, then a protectorate of India. While there are several claims and counter claims from each side, the cause of these incidents was similar to the earlier border clashes of 1959 and 1962 i.e. troops coming in contact while the Indian army was putting-up border markers along with some other trivial issues42. However, more significant was an event in 1987 when the second border war between the two was predicted43. In this case too, a similar event occurred when the Indian army had started patrolling areas north of the demarcated McMahon line as far back as 1984. This was after India politically granted NEFA the status of a province but being disputed, the Chinese objected to the same. Consequently, the Chinese once again consolidated their positions. When the Indians found out, they airlifted a Brigade to the area and war was imminent. Nonetheless, by the summer of 1987, both sides disengaged and diplomacy, though antagonistically applied, did prevail. This incident coincides with a revived aggressive Indian policy of securing its frontiers and the Siachen glacier issue with Pakistan that also commenced in 198444.

17. Nevertheless, the first modern day incident occurred in 2013 when both countries’ ground forces took up aggressive postures with counter claims in the Aksai Chin area45. The two withdrew after diplomatic efforts with India dismantling few border posts that were viewed as aggressive Indian posturing by the Chinese. Hence the cause of the incident is yet again related to Indian advances in a region that was required to remain demilitarized as per pre-1962 positions i.e. the convention being followed after the Chinese withdrawal after the war of 1962. Again in September 2014, a standoff occurred in the south of Aksai Chin as India started construction of a canal that was resisted by the local Chinese population46. After three weeks of standoff, both sides pulled back due to hectic diplomatic efforts.

18. The incident of 1987 occurred while there were gradually improving diplomatic relations between the two and mutual visits by important dignitaries including PMs from both sides had concluded. However, the last two incidents i.e. 2013 and 2014 occurred much later when trade, commerce along with diplomatic relations between the two significantly improved. Note that bilateral trade exceeded US $73 Billion in 2012 and was targeted to exceed US $ 100 Billion. The seemingly improving relations were met with exceptions as explained above. Even the 2013 event had occurred days before the Chinese PM visit to India (Pakistan should draw important lessons). What can be drawn from the 1962 Indo-Chinese war in terms of regional stability is that it has and continues to be assessed as threat to regional stability. Some assess these relations as strategically stable but with tactical anxiety. A rather mild view of the situation.

19. However, going by Maxwell’s analyses supported by other facts mentioned above, the Indian army’s overall line of action in this conflict does appear to occasionally adopt pre-1962 war tactics. This is the shade of gray that is perhaps or could be transforming into the dark side of the story and would require a completely separate research. Without over simplifying, it can be explained that the Indian army, by nature of Indian political system, cannot act independently. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that when shades of aggressive politics are accompanied by domestic political compulsions, these set a belligerent mood in India. This was the setting and method applied by Nehru, the military hierarchy and his political opponents before the aggressive forward policy was formulated and applied. As elsewhere, often this mood is generated by a congregation of individuals with hawkish political mindset47 like unifying the nation through war– a repeat of 196248, 1987 and perhaps recently in 2014 – a factor that Pakistan must keep in view when the bravado of the Shiv Sena of today comes through the Indian parliaments. Unfortunately, after arrival of the new Indian political leadership of Mr. Modi with the controversial Shiv Sena (read also as Gujarat riots of 2002) related background, further possibilities of enhancement in tensions cannot be ruled out49. In essence, this dark side may potentially also impede progress made between the India and China. However, there is yet another side of this conflict that needs elaboration to further complete the picture i.e. this was a military conflict between two of the worlds large and rising states. Each brought with itself its friends and allies – a factor that shaped the dynamics of strategic alliances and continues to do so till date!

Analysis of the World of Strategic Interests and Alliances: Past, Present and Future

20. From the military forces application point of view, all incidents including the 1962 war were tactical manoeuvres conducted by tactical sized forces i.e. only three divisions or equivalent strength from each side were involved in 1962 war50. However, the ensuing political and military contest between India and China resulted in certain strategic effects. An overview of these relationships using the 3G (Geopolitical, Geo-economic and Geophysical) analytical51 tool would therefore be beneficial to comprehend the wider effects of this conflict. Moreover, the ensuing strategic partnerships can be seen in light of the background of Indian political stance at regional and international level. When it comes to strategic alignments and blocs, it is motivated by state interests and events.

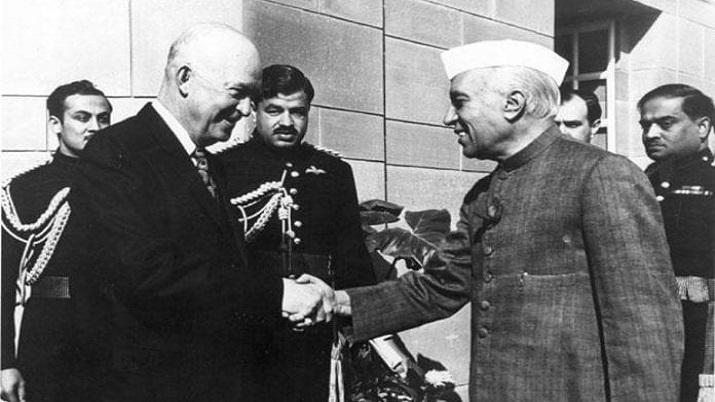

21. Firstly, regarding alignment of regional players and then the great powers. Interestingly, since independence, India had strongly adopted and steadily solidified its stance as a non-aligned state i.e. it was not a member of the US (western) or Soviet Bloc. In fact, India was the de facto leader of the Non Aligned Movement (NAM) of Afro-Asian states – only to be rejected by most after the 1962 war52. Nevertheless, India had continued to receive economic assistance from USA since 1947 that increased as tensions enhanced with China after 195953. Subsequently, as initial Chinese reactions became evident after their forward patrols were engaged, the Indian leadership pleaded to the US in secrecy for assistance. Thus, US emergency aid and later British military aid was made available before the intense fighting in 1962. The reason was simple – India was a symbol of democracy while China was a communist power. Actually, short of the main military engagements, Indian army’s assessment was the necessity to involve US tactical airpower to hold the Chinese. Upon request, a US aircraft carrier was also dispatched to the Bay of Bengal but was too late to intervene and turned back before deploying54. All this was in addition to the ongoing assistance by USSR. Note that India-USSR relations had been initiated earlier by mutual visits between Nehru and Khrushchev in 1955 as a part of Soviet attempts to influence Third World Countries. Therefore, economic, trade and military relations between the two had commenced much to the disliking of Mao. But during this conflict, USSR was recovering from the Cuban Missile crisis of mid-196255. Thus, USSR was neither in a position to antagonize the West nor did it want to close its options with India. Simultaneously, it also consented to the Chinese requirements in 1962 for defending their own territory, should the Indians cross the traditionally accepted geophysical boundaries between them.

22. Whereas, Indo-US relations date back since post-independence era, they were strengthened by Eisenhower’s visit to India in 195956. Unknown to many and never accepted openly, US economic aid had flowed to India since the post-independence era. In 1962, India clearly depended on the West and in particular USA when the conflict was unfolding. Hence, on one hand, despite its NAM posture to the world and domestic audience, the Indian government followed a policy of western alignment by playing the anti-communist role of containing the Chinese only. On the other, it also successfully followed a policy of dual front by keeping the Soviet’s engaged and supportive – a repeat of these would be visible decades later.

23. That the pre-partition Indian border demarcations had several issues is widely known. It is also equally understandable that due to the dynamics of the partition process and historical perspective of cultural factors, India has always maintained certain amount of hostility towards Pakistan. Nonetheless, during the mid-1950s to early 1960s, China had peacefully settled border disputes with Myanmar, Nepal and Pakistan57. In fact, initial Chinese assessment had expected the Indian issue would be relatively simpler. It is interesting to note that in the years before settlement of the border demarcation issue, Pakistan was apprehensive about China regarding her possible expansionist policy (as normally perceived at that time). Thus Pakistan had initially proposed a joint defence pact with India, only to be rejected by Nehru58. Under a separate set of circumstances i.e. apprehensions of Soviet communist expansion, Pakistan was also a member of the now defunct SEATO and CENTO since 195459. Nevertheless, after western military assistance to India in 1962, Pakistan feared that the same could be used against it. Later, in the backdrop of USSR’s continued assistance to India and subsequent US embargo60 on Pakistan after the 1965 war with India, relations with China progressively improved61.

24. Separately, during the late 1950s, China had started to drift away from the USSR due to its own border quarrels62 but most importantly due détente63. Therefore, while today’s reasons may differ up to a certain degree, it is clear that the bloc and allied-state realignment was evident through the mid-1950s – 60s. This was prominent in 1962-65 (as transition years), as the US would continue to leverage India against China. This, as evident, exists till date albeit greatly improving economic, trade and technology improvement and military ties with USA. Therefore, in the era of 1960s, it was never really ‘NAM’ as openly stated. India always maintained dual bloc relations with Russia and USA in Diplomatic, Informational, Military and Economic (DIME64) spheres to improve its instruments of power – these also exist today. The exception is that it is accompanied with positive attempts to diplomatically and economically improve relations with China while aggressively following a policy that is benign on the face. The motivation has improved stability in relations, trade and of course, the overall business.

25. Viewed from the lens of Indo-China conflict, the differences from 1962-65 are also important. While Pakistan still maintains very friendly relations with China, it definitely enjoys a love-hate relationship with the US since the 1965 war. It is dependent upon USA in several ways including the stability of the region in context of the Afghan issue. Overall, Pakistan is no longer as strong a US ally since Russian expansion is no longer valid in South Asia. It is only a US partner in regional Counter Terrorism efforts with several concerns from both sides. While Pakistan has only recently started to improve relations with Russia, the context is totally different. However, the Sino-Russian relationship65 is steady with improvements since post Mao era of 1980s and after the demise of USSR. Another major contextual difference is that US-China relationship66 is totally transformed. In brief, besides issues East of China with Taiwan and the ownership of islands in South China Sea, it is transitioning beyond economic competition and economic interdependence with USA. To the Pacific states and USA, it is less about the fear of communism spreading. Now, it is more about ‘which system of governance is better’ and that ‘who would dominate the world in the future’. Similarly, despite its economic dependence on the west including USA and EU, Russia has politically drifted, specifically from USA and is following its own path. Perhaps it is an attempt or drive to revive its USSR-like political might and military status at global level. For these and other strategic factors, it is more cooperative with China.

26. Finally, compared to 1962, there is one more aspect regarding India i.e. stronger US – India relationship that is in synchronization regarding each one’s counter-balancing strategy against China, at least in the Indian Ocean. These are the ingredients of developing near-strategic interests of both USA and India. Depending on circumstances, theoretically, it can play positive in Indo-China relations or the converse. The recent Indian attempts to stretch itself towards Vietnam and Japan, possibly as a counter to the Chinese string of pearls; and in support of US Pacific pivot can be interpreted in the same context67. Hence, Indian diplomatic and military ventures in the strategic domain including development of her air force as an aerospace force, the Indian navy as a blue water navy, expeditionary role for the army (called Out of Area Operations capability), massing forces for a two front scenario (against China and Pakistan), improved range Ballistic and Undersea Missiles and nuclear arsenal enhancements are in the context of her political and mythical psyche of Bharat. Viewed in the context of 1962 war, these developments, if played negatively, can be considered to possess the potential to destabilize not only South Asia but other regions as well. In this complex web of geostrategic, geopolitical and geo-economic factors between regional and global players, these are the intertwined, sometimes drifting and conflicting connections between nation-states based on national interests.

Conclusion

27. While there are many lessons and conclusions that can be drawn from this expose regarding our topic, in essence, we have considered six main factors while analyzing the 1962 Indo-China war. Chronologically,

(a) First is the history of the problem. Though complex but neither difficult to comprehend nor resolve, at least technically. Since it has a cultural context with customary understanding and perhaps folklore on Indian side, it remains unresolved. For resolution, the traditional Indian biases would need to be overcome by Indians themselves specifically the BJP/ RSS type hawks.

(b) Second is that diplomatic, informational and specifically economic relations between India and China are steadily improving based on a generation of efforts from both. These are the reasons that we should remain optimistic regarding their future relations. It must be though noted that economic cooperation was initiated to improve diplomatic relations and is not ‘critical’ in the sphere of either’s interdependence.

(c) The third point we considered was the scars of the 1962 war, specifically on India and the ensuing tensions with the two recent border incidents of 2013 and 2014. This counteracts the second factor (above), and that recurrence of such skirmishes or recent tactical standoffs (as late as 2016), though never desirable, cannot be totally ruled out. This is also a lesson, that business is business and that a diplomatic exchange involving sipping a cup of tea is just that. Hence, economic and trade relations can alone seldom deactivate tensions specifically in issues of national sovereignty and interests, this is something some in Pakistan yet need to understand.

(d) Fourth is about global relationships; bloc alignments and the drive towards multipolarity in the 21st Century. Although the Indo-Russian relationship continues to be time tested, India has diversified its military import sources. Nevertheless, there are still many mutual military (as recent as 2016) and economic cooperation projects. Conversely, Russia and China are now much more strategically closer compared to 1962. Although each would take care of its own interests, Russia would need to walk a much more careful path should there be any future Indo-Chinese conflict. Similarly, Russian politico-military support to India may not continue as it did in 1962. Therefore, the altered 3G (Geopolitical, Geostrategic and Geo-physical) priorities now affect previous regional strategic alignments and would place restrictions on India while allowing more strategic leverage to China.

(e) The fifth and dominant factor is that Indo-US relations are stronger and steadier than 1962 and span across the diplomatic, informational, economic and military realms. Each has mutual 3G benefits in this relationship along with achieving counterbalance against China in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). In the wake of increasing and open US support to India against China, India would really only need continued diplomatic support from its other allies. Recent examples include agreement on the signatures to a Logistics Exchange MOA (LEMOA) allowing USN and IN warships to replenish at each other’s ports. Another factor that we in Pakistan need to take care of in the 21st Century environment of multipolar and interchanging and floating coexistent Blocs.

(f) But beyond these five is lastly the most important and intrinsic factor that dominates the remaining i.e. India itself is the most important player regarding the future of this frozen conflict. After all, the conflict did start as a result of miscommunications, non-negotiating aggressive attitude, incorrect military advice and miscommunication between political and military leadership in India. Then, the fuel to the fire was from internal Indian politics (specifically from the BJP/VHP/RSS aggressive stance) combined with hawkish political inputs along with media outburst and public pressure something we in Pakistan must be able to read, should the events start to snowball. Today, the Indian internal political structure is getting more aggressive under the BJP and Mr. Modi along with a military that wants to become more vocal as it gains more muscle. In today’s media intense world, any minor incident can easily spin out of control with the aforementioned ingredients, whether for China or Pakistan. Then, other external factors of geostrategic alignments can come-up to play their role – positive or negative – as per the national interests of the regional and international players. Indeed, while there are reasons to remain optimistic about the improving political and economic factors in the conflict between India and China, there are at least an equal number of reasons that foretell that care must be exercised as any minor event can trigger another military confrontation. For example, any minor incident between patrolling Indian and Chinese Navy warships in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

28. In quintessence, for a combination of these six reasons including external and internal factors within India and China, it could be argued that, excluding economic dividends, the overall balance of assessment is that the 1962 Indo-Chinese war had and could continue to negatively affect regional stability even in the 21st Century. If aggravated, it can very easily affect global stability. Based on the available evidence, while the responsibility in-principle is on both sides, it appears to be higher on the Indian political leadership and it’s military. Both would need to monitor several internal politico-military aspects and should be kept under their control within India.

Bibliography

Bungay, Stephen. “Moltke: Master of Modern Management. The European Financial Review, April-May 2011, 54.

CIA FOIA. The Sino-Indian Border Dispute Section 2. www.foia.cia.gov/sites/default/files/document …/14/polo-07.pdf (accessed 10 January, 2015).

CIA FOIA. The Sino-Indian Border Dispute Section 2. www.foia.cia.gov/sites/default/files/document…/ 14/polo-08.pdf (accessed 10 January, 2015).

CIA FOIA. The Sino-Indian Border Dispute Section 3. www.foia.cia.gov/sites/default/files/ document…/14/polo-09.pdf (accessed 10 January, 2015).

Diplomat Staff. “India’s Top Secret 1962 China War Report Leaked”. March 20, 2014. http://thediplomat.com/2014/03/indias-top-secret-1962-china-war-report-leaked/ (accessed 12 Jan 2015)

Global Security. Org. “India-China Border Dispute”. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war /india-china_conflicts.htm (accessed 22 January, 2015).

Gurmeet Kanwal, India’s Military Modernization: Plans and Strategic Underpinnings, (The National Bureau of Asian Research), September 24, 2012,

http://www.nbr.org/research/activity.aspx?id=275 (accessed 03 January,2015).

Hedrick, Brian K, “India’s strategic defense Transformation: Expanding global relationships”, (Research paper of US Army Strategic Studies Institute), November 2009,

http://www.strategicstudies institutearmy.mil/pdffiles /PUB950.pdf (accessed 02 January, 2015).

Maxwell, Neville. “India’s China War”. Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970).

Mizokami Kyle, “Five Indian Weapons of War China Should Fear”, (The National Interest, June 21, 2014),

http://nationalinterest.org/feature/five-indian-weapons-war-china-should-fear-10714 (accessed 04 January, 2015)

Platias, Athanassios G & Koliopoulos, Constantinos. Chapter 1: Grand Strategy: A Framework for Analysis, In Thucydides on Strategy, 1- 21, London: Hurst, 2010

Saha, Subrata. “China’s Grand Strategy: From Confucius to Contemporary”. Research paper USAWC Class of 2010.

Stevenson, David. From Balkan Conflict to Global Conflict: The Spread of First World War, 1914-1918. Pp-170 Foreign Policy Analysis. Volume 7, Issue 2, 169–182, April 2011.

Steven, Jeremy, Strategy for Action, Framework for Thinking Chapter-9 in Strategy for Action, 198.

“Von Clausewitz, Carl (Karl) Quotes”, Military Quotes, http://www.military-quotes.com/clausewitz.htm (accessed 4 January, 2015).

Wikipedia. “The Chola Incident”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chola_incident (accessed 2 Dec 2014).

Wikipedia “Détente”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%C3%A9tente (accessed 10 January, 2015).

Wikipedia. “Sino-Indian skirmish” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1987_Sino-Indian_skirmish (accessed 2 Dec 2014).

Wikipedia. “Sino-Indian War”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Indian_War (accessed 2 Dec 2014).

Wikipedia. “Events leading to the Sino-Indian War”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Events_leading_to _the_Sino-Indian_War . (accessed 12 Jan 15).

Wikipedia. India–Russia relations. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/India%E2%80%93Russia_relations (accessed 18 January, 2015).

Wikipedia. “Sino-Indian border dispute”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Indian_border_dispute (accessed 19 January, 2015).

Wikipedia. “The Daulat Beg Oldi Incident”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2013_Daulat_ Beg_ Oldi_ Incident. (accessed 14 January, 2015).

Wikipedia. “McMahon Line”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/McMahon_Line (accessed 10 January, 2014).

Wikipedia. “Siachin Conflict”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siachen_conflict (accessed 22 January, 2015).

Wikipedia. “Frozen Conflict”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frozen_conflict (accessed 08 January, 2015).

Wikipedia. “MaCartney–MacDonald Line”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macartney%E2%80%93 MacDonald_Line. Accessed 10 January, 2015)

Wikipedia, “India-US Relations”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/India%E2%80%93United_States_relations (accessed 12 January, 2012)

Wikipedia, “Sino-Indian skirmish”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1987_Sino-Indian_skirmish (accessed 2 Dec 2014).

Wikipedia, “India–Russia relations”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/India%E2%80%93Russia_relations (accessed 18 January, 2015).

Wikipedia, “Macartney–MacDonald Line”,, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macartney%E2%80%93 MacDonald_Line (accessed 10 January, 2015).

Wikipedia, “Frozen Conflict”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frozen_conflict (accessed 08 January, 2015).

Wikipedia, “Indian Integrated Guided Missile Development Program”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integrated _Guided_Missile_Development_Program (accessed 30 December, 2014).

Wikipedia, “China-India Relations”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China%E2%80%93India_relations (accessed 3 Jan 2015)

Wikipedia, “Narendra Modi”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narendra_Modi (accessed 22 January, 2014).

Wikipedia “Pakistan-US Relations”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pakistan3United_States_relations (accessed 19 January, 2015).

Wikipedia “Sino-Russian Relations”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Sino-Russian_relations (accessed 9 January, 2015).

Wikipedia “China-US Relations, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China%E2%80%93United_States_relations (accessed 9 January, 2015).

End Notes

1 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son limited, 1970), 261.

2 Ibid, 79.

3 Ibid, 20-27.

4 Ibid, 28-30

5 Ibid, 21, 41, 63-64 and title page.

6 Ibid, 13.

7 “Carl (Karl) von Clausewitz Quotes”, Military Quotes, http://www.military-quotes.com/clausewitz.htm (accessed 4 January, 2015).

8 “Frozen Conflict”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frozen_conflict (accessed 08 January, 2015).

9 Refer to subsequent explanation of more related events.

10 Brian k. Hedrick, “India’s strategic defense Transformation: Expanding global relationships”, (US Army SSI), Nov 2009, http://www.strategicstudies institute army .mil/pdffiles/ PUB950.pdf (accessed 02 Jan, 2015).

11 “Indian Integrated Guided Missile Development Program”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integrated _Guided_Missile_Development_Program (accessed 30 December, 2014).

12 Gurmeet Kanwal, India’s Military Modernization: Plans and Strategic Underpinnings, (The National Bureau of Asian Research), Sept 24, 2012, http://www.nbr.org/research/activity.aspx?id=275 (accessed 03 Jan, 2015).

13 Kyle Mizokami, “Five Indian Weapons of War China Should Fear”, (The National Interest, June 21, 2014), http://nationalinterest.org/feature/five-indian-weapons-war-china-should-fear-10714 (accessed 04 January, 2015)

14 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970),11.

15 Ibid, 39-64.

16 “Sino-Indian War”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Indian_War (accessed 2 Dec 2014), 2.

17 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970),76.

18 “China-India Relations”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China%E2%80%93India_relations (accessed 3 Jan 2015), 2.

19 Sino-Indian War”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Indian_War (accessed 2 Dec 2014), 2.

20 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970), 87.

21 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970),77,79,80.

22 “China-India Relations”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China_relations (3 Jan 2015), 5.

23 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970),83.

24 Ibid, 131-134.

25 Ibid, 247-248.

26 Ibid, 174-177, 235.

27 Ibid, 135, 155, 163-6.

28 Ibid, 179-185, 191-193.

29 Ibid, 234.

30 Ibid, 243-245.

31 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970),335, 338.

32 Ibid, 384.

33 Ibid, 414.

34 “India’s Top Secret 1962 Report Leaked”, The Diplomat Staff, March 20, 2014, http://the diplomat.com/2014/03/indias-top-secret-1962-china-war-report-leaked/ (accessed 12 Jan 2015)

35 “China-India Relations”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ChinaIndia_relations (3 Jan 2015), 7.

36 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970),422.

37 “China-India Relations”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ChinaIndia_relations (3 Jan 2015), 5-7.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid, 1.

40 Ibid, 5-8.

41 Wikipedia. “The Chola Incident”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chola_incident (2 Dec 2014).

42 Wikipedia. “Sino-Indian border dispute”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Indian_border_dispute (19 Jan, 2015).

43 Wikipedia. “Sino-Indian skirmish” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1987_Sino-Indian_skirmish (2 Dec 2014).

44 Wikipedia. “Siachin Conflict”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siachen_conflict (accessed 22 January, 2015).

45 “The Daulat Beg Oldi Incident”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2013_Daulat_ Beg_ Oldi_ Incident (14 January, 2015).

46 “India-China Border Dispute”, Global Security. Org, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war /india-china_conflicts.htm (22 January, 2015).

47 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970),176-177.

48 Ibid,362-364, 438-443.

49 “Narendra Modi”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narendra_Modi (accessed 22 January, 2014).

50 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970), 425.

51 The 3G Methodology: A Practical Approach to Strategic Foresight, RCDS Synopsis, 16 December, 2014.

52 Ibid, 251-252, 262-264.

53 Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970), 378.

54 Ibid, 411.

55 Ibid, 423.

56 “India-US Relations”, Wikipedia,http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/India%E2%80%93United_States_relations (accessed 12 January, 2015).

57 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970), 425.

58 Ibid, 206.

59 Ibid, 207.

60 “Pakistan-US Relations”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pakistan%E2%80%93United_States_relations (accessed 19 January, 2015).

61 Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, (Worcester and London: Ebenezer Baylis and son Limited, 1970), 275.

62 Ibid, 285.

63 “Détente”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%C3%A9tente (accessed 10 January, 2015).

64 R Hilson, “DIME/PMESII Model Suite Requirements Project”, DTIC, Information Technology Division, www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA525056 (accessed 20 January, 2015)

65 “Sino-Russian Relations”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Sino-Russian_relations (accessed 9 January, 2015).

66 “China-US Relations”, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China%E2%80%93United_States_relations (accessed 9 January, 2015).