Pakistan has mostly dealt with its water security issues from technical and political point of views, and has rarely explored any legal options. There are serious capacity issues with regard to legally contesting our cases at international forums; this has led to a mindset of reactive approach based on patchy and ad-hoc measures. There is no substantive victory to our credit with respect to earlier matters that we pleaded at international forums. There is hardly any Pakistani expert in international water laws, hence every Tom, Dick and Harry is an expert.

The water issue is quite politicked both in India and Pakistan. Every time there is a decision by neutral experts or arbitration courts, both countries simultaneously claim victory. India has an inherent mindset of smallness with respect to neighbours in general, and has serious water issues with all adjoining states. For India the whole affair of tampering with the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) may be a political gimmick, but for Pakistan it carries high stakes. And Pakistan should act accordingly.

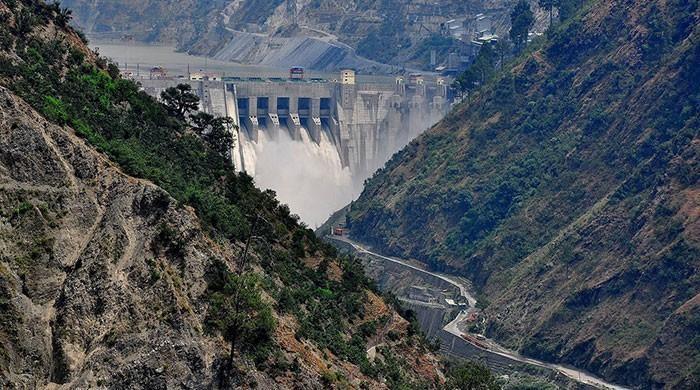

The World Bank (WB)—the underwriter of ITW— has self-imposed a temporary pause with regard to its mandatory role of Treaty arbitrator. The clumsy reason advanced by the WB is that the tangential stances taken by the two sides might harm the treaty. The Bank has halted the processing of appointing a Neutral Expert as demanded by India, alongside Pakistan’s request for appointing Court of Arbitration’s Chairperson, for bridging the divergent opinions over building of Kishenganga and Rattle dams by India, in contravention to IWT. It is for the first time since the IWT became operational that the WB has halted the arbitration process. “Both processes initiated by the respective countries were advancing at the same time, creating a risk of contradictory outcomes that could potentially endanger the treaty”, said the handout. But as Pakistan was first to apply for appointing the Chairman of the Court of Arbitration, the WB should not have considered India’s request for appointment of Neutral Expert.

The WB announced the pause the day it was supposed to appoint the Chairman for the Court of Arbitration. “We are announcing this pause to protect the IWT and to help India and Pakistan consider alternative approaches to resolving conflicting interests under the treaty and its application to two hydroelectric power plants,” said WB Group President Jim Yong Kim. “I would hope that the two countries will come to an agreement by the end of January,” he added.

WB’s spokesman Alexander Ferguson while responding to a question whether the WB has accepted India’s position by pausing the process said, “The announcement is consistent with the WB’s historic role as a neutral, pragmatic and proactive partner to both countries and is without prejudice to the processes initiated by [them].” It has not been clarified as to what WB perceives as ‘alternative ways’ and how it assumes that the two governments could resolve their differences. The development is worrisome in the context of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s hint at abrogating the treaty unilaterally and an Indian announcement in November that it would not participate in the process of appointment of Chairperson.

If India and Pakistan were capable of resolving the matters bilaterally, there would have been no need to have an IWT and things would not reach such a pass and that too so frequently. WB President’s intent may be decent but he may observe that implications of pause are quite harmful to Pakistan unless World Bank’s halting of the two processes was accompanied by a simultaneous directive asking India to suspend construction work on the two dams in question. Pakistan has suffered on this account because so much of procedural delays occurred in Baglihar Dam that by the time the matter reached a neutral umpire, the dam was already complete; though in his reward the neutral umpire held that dam had violated the IWT by incorporating a storage enabling design of gates, it was cordoned as fait accompli.

By requesting for detailing the Chairman of the Court of Arbitration, Pakistan has only exercised one of its rights as stipulated in the text of the IWT, so apparently there is no plausible reason for denying this request. Pakistan had approached the Bank for arbitration after exhausting all bilateral discussions. WB needs to act as the guardian of IWT and should avoid taking a stance that could encourage India to follow a deviant trajectory. Under the Treaty, the only other option was taking up the matter at the Permanent Indus Commission level. Both the countries have already exhausted this option and availing it again would not resolve the disputes.

The WB’s role has been made clear, it must gather courage and take this issue head-on. In November last year India had refused to take part in the Court of Arbitration established by the World Bank to solve the Kishenganga dispute with Pakistan, stating that “it was legally untenable to set up two parallel dispute mechanisms”. The Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Vikas Swarup had said India could not be party to actions which were not in accordance with the IWT.

India had long ago taken a deliberate decision to use water as an economic weapon against Pakistan. Narendra Modi recently said: “The fields of our farmers must have adequate water. Water that belongs to India cannot be allowed to go to Pakistan”. The well thought out strategy followed by India is of incrementally building dams along tributaries of the Indus River deliberately designed to trap water. Constitution of Court of Arbitration and Neutral Experts is meant to decide whether such dams fall within IWT provisions or not.

The Treaty is neither time barred nor event specific and is binding on both countries with no exit provision. According to Article XII of the IWT, the treaty cannot be altered or revoked unilaterally. The Treaty is inherently self-guaranteeing and self-healing in nature. Indian Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Vikas Swarup conceded to this fact: “India remains fully conscious of her international obligations and is ready to engage in further consultations on the matter of resolving current differences regarding these two projects”. India will be too happy to have IWT relegated to bilateral status and do with it as it is doing with other issues and disputes.

IWT is a regulatory framework; it does not specify the number of dams that India could build. However, international law declares a positive obligation, for all states to not inflict unreasonable harm on the lower riparian state. The Treaty itself is a non-negotiable matter, however dialogue could be held to remove any doubts and ambiguities. Adviser to Prime Minister on Foreign Affairs Sartaj Aziz said that Pakistan’s foreign office would issue a statement after reviewing the World Bank’s press release. Pakistan’s Indus Water Commissioner Asif Baig also declined to comment before taking a thorough stock of the matter. The eventuality should have been anticipated and suitable response should have been ready.

Pakistan needs to view the development seriously. India is not likely to pull out of the Treaty but would do anything to erode its provisions that safeguard Pakistan’s interests. The entities responsible for handing ITW matters are certainly in for a long haul and need to prepare for that appropriately.

At the same time, there is a need to enhance capacity of our Foreign Affairs and Indus Water Commission with regards to comprehension of legal aspects of the Treaty and other international water laws. ITW is a Pakistan-India specific treaty based on division of rivers between India and Pakistan and not on sharing of water, except when otherwise provided in the Treaty, for specific purposes and in stipulated quantities. Unnecessary referral to other laws as well as riparian concept is only likely to dilute our stance.