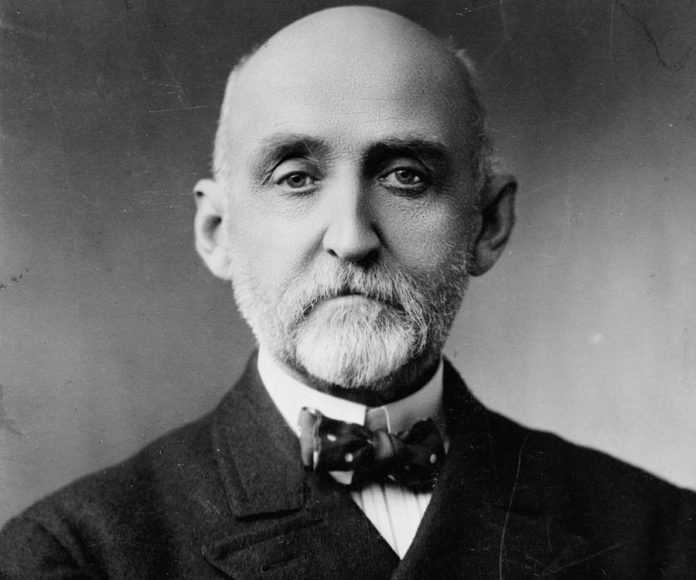

The contesting maritime claims and conflicted sea-lanes along with unyielding clashes over key water paths, main straits, major canals and important ports always remind about the significance of Mahanian political model in international politics. The doctrinal attributes of Mahanian model enunciates an undeniable role of sea power in strategic clashes of great powers. As a proponent of sea power under oceanic politics, Alfred Thayer Mahan supports the notion of naval supremacy for economic dominance through the seas. As a US naval admiral and one of the prominent strategists of nineteenth century, Mahan became the father of modern naval warfare. The advancement of modern naval strategies and development of strong naval muscles under Blue–Water school are formalized by Alfred Mahan. Mahan’s intellectual propositions emphasise the role of a robust naval force in world politics. He prefers the role of maritime power over land power by highlighting the essence of battleships in effecting the outcomes of wars. Mahan’s ascendency in naval school of thought focuses on significance of the state’s strong maritime position in international system. A systematic examination of Mahan’s intellect and its application on contemporary world politics leads the debate toward China’s emerging role in the world affairs. The idea of developing navies in the seas and nations in the oceans to influence the oceanic politics refers to a strong naval leadership which could not only help a state to defend its commerce in the sea but it also empowers the state to counterbalance its rivals in the waters. The adherence to Mahan’s doctrine of sea power has become an enduring feature of world politics in which the evolving models of power politics in international relations are still revolving the role of unbroken oceans and connecting seas. The importance of seas in strategic calculations of states reflects the influence of Mahan in strategic thinking of leaders.

The blue water ambitions of the People Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) towards first and second islands chain in the Pacific Ocean and development of ports in Indian Ocean reflects the Mahanian influence in Beijing’s strategic mind-set. The fundamental imperative for full implementation of Mahan’s doctrine for obtaining effective command of sea shapes the modern strategic thinking of China under The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road. The combination of continental or land–based Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and a widespread network of ports under Maritime Silk Road (MSR) usually denotes China’s Belt–Road Initiative or One Belt, One Road (OBOR) plan. The MSR, formally introduced by the Chinese President in 2013 is introducing a new shipborne paradigm of maritime politics to create China’s seaborne deterrence. By actively involving more than sixty countries in Beijing’s mega economic plan, China will be able to strengthen its strategic positions across Asia, Europe and Africa. Contrary to multilateral framework of economic agreements, Beijing preferred to follow bilateral patterns in Belt–Road Initiative. The feasible bilateral trade deals with different states will solely provide economic advantages by empowering its strategic standing in world politics.

The South Asian version of MSR under OBOR has resulted in China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). A decent pattern of Beijing’s economic diplomacy attracted Islamabad to Chinese sponsored model of regional integration through regional connectivity by massive development of ports and coastal areas of Pakistan. The CPEC emphasized the construction of deep–water Gwadar port which will serve Chinese commercial interests in future. The critical circles of international community view Beijing’s mega plan of CPEC as a strategic gambit laced with serious consequences for entire region. The Chinese strategic interests in the Indian Ocean are inherited in Gwadar. The construction of Gwadar port will strengthen China’s position against the swelling naval capabilities of India. Therefore, the signing of CPEC under Belt–Road Initiative is going to mainly alter traditional wisdom of Pakistan’s national security. The Indian concerns over growing Sino–Pak economic cooperation under CPEC are difficult to ignore. The traumatic historical accounts of Indo–Pak rivalry must be considered seriously by Islamabad and Beijing mutually. The dramatic Indian response has proposed India–China–Silk Route Corridor (ICSRC) based on Ladakh–Xingjian connection as a substitute of CPEC. New Delhi is basically cautious about the emerging Sino–Pak bilateral economic cooperation which will boost strategic relations of both neighbours. Indian anti–Pakistani behaviour further supports Iran’s Chahbahar port project by activating New Delhi’s connections with Tehran and Kabul. The promotion of contrast development schemes has further resulted in India’s support to the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a multi-link model of European and Central Asian states to connect New Delhi, Moscow and Tehran in mega connectivity plan.

In response to the construction of Gwadar port, a source of maintaining Beijing’s access across Asian states and PLAN’s strategy to influence Indian Ocean, New Delhi is considerably stretching its naval muscles while establishing seaborne deterrence. Apart from developing alternate connecting economic projects, India is seriously improving its naval strategies equivalent to mammoth economic policies. The gigantic naval arrangements in the South Asian subcontinent has resulted in Indian nuclear capable submarine (INS Arihant) which has considerably granted New Delhi a nuclear triad force. The Submarine–Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM) under three–branched nuclear capability has already undermined Pakistan’s strategic position in the region. Moreover, a six fold strategy of increasing naval spending, strengthening naval infrastructure, increasing naval capabilities, arranging naval exercises along with active naval diplomacy and influencing the chokepoint in and out of Indian Ocean is portraying a worrisome future for neighbouring states. In this way, the greater naval capabilities based on high budgetary allocation, vast naval command based on Western, Eastern and Southern command, maritime capabilities for implementing a robust maritime military strategy, diplomatic naval strings to enhance cooperation with other states coupled with practicing various models of naval exercises and ambition to control the strategic points of Indian Ocean, exclusively the straits, are broadly the belligerent components of Indian naval posture. The inclusion of extra–regional powers to augment New Delhi’s naval strength in oceanic politics has not only resulted in construction and purchasing of more naval capabilities and their timely deployment, but it has also exploited the strategic ambitions of counterbalance forces like China.

The maritime aspirations of both states, China and India, extensively hamper Pakistan’s strategic thinking by inflicting a sense of insecurity and strategic vulnerability in Islamabad’s perception–set. India’s audacious naval advancements coupled with New Delhi’s maritime infringements in the Arabian Sea are repeatedly forcing Pakistan to react accordingly. Both Beijing and New Delhi have undoubtedly learned Mahan’s philosophy “Who controls the seas controls the world” and applying it properly. The strategic community from both states have learned Mahan’s ideas of naval development and applied it for reorganizing the Asian regional order. The burgeoning less economic–more strategic interests of both states are vividly analogous to the Mahanian model of world politics.

The rapidly growing influence of Mahan’s philosophy in Chinese strategic thinking directs the neighbouring states to follow Beijing’s footsteps. Mahan, as an espouser of maritime politics, focuses on the acquisition of chokepoints and an active control of seaborne trade is prerequisite to secure a status of great power. The economic development through maritime commerce introduces prosperity and noticeably support to a state to become a great power in international relations. The gaining of a prestigious status of an economic power further activates an economic competition which forces the states to empower their navies. The naval advancement based on maritime commerce–riding strategies help economically strong states to defend their strategic position in the oceans by subduing the rival forces in the seas. Mahan’s geostrategic thoughts, in this way, support the notion of naval supremacy.

Beijing obsessed with Mahanian politics is ambitious to influence the oceans along with terrestrial routes. The aspiration of global dominance by countering the antagonistic alliances of adversaries forced China to chalk out OBOR. The Beijing’s maritime planning is primarily designed to counter Indo–US strategic partnership which is not only a severe threat to PLAN in Arabian Sea, but it also has become a potential threat in South China Sea. Moreover, the rapidly evolving trilateral naval association of Japan, India and US is forcing China to increase its naval interaction with other states. Therefore, China’s enlarged naval role is primarily a strategy to counter Washington’s policy of encircling Beijing. The South Asian version of this great game is dragging Pakistan towards the Mahanian model of naval power politics.

A complex matrix of significant but varied nature of maritime security challenges are formulating South Asian future politics. Pakistan, which is not a maritime state will profoundly become a gravitational point of oceanic politics of subcontinent. A maritime Pakistan is sturdily becoming an undeniable reality for Islamabad. Therefore, it is essential for the leading national security architectures of Pakistan to define Islamabad’s strategic position in Indian Ocean while polishing the state’s naval muscles. The regional engagement of South Asian states in maritime politics needs the active performance of maritime thinkers in mainstream policies of Islamabad. A vivid application of Mahan’s intellect will be the subcontinent’s future in which a well prepared naval force with technologically advanced weaponry will be able to effectively neutralize maritime contingencies in Indian Ocean. In short, the burgeoning naval competition based on an environment of changed naval doctrines, updated naval strategies and non–traditional maritime postures of New Delhi and Beijing in South Asia are pushing Pakistan to modify its traditional values of national security. Now, it is necessary for Islamabad to pragmatically determine its naval standing between adversarial India and economically powerful China instead of unrealistically visualizing South Asian future.