We have done with hope and honour;

We are lost to love and truth.

We are dropping down the ladder rung by rung,

And the measure of our torment is the measure of our youth.

God help us, for we knew the worst too young;

Our shame is clean repentance for the crime that brought the sentence.

And we die and none can tell them where we died,

We’re poor little lambs, who’ve lost our way,

Baa’ Baa’ Baa

Gentlemen-rankers out on the spree,

Damned form here to eternity’

God ha’ mercy on such as we,

Baa, Yah, Baa

Rudyard Kipling

54th Regiment of Foot was a regiment of the British army having a long and illustrious history of two hundred and fifty years went through various transformations. It was raised in 1755 as 56th Foot by Colonel John Campbell. In 1756, when two senior regiments (50th & 51st Foot) were disbanded, 56th became 54th. It was also called West Norfolk Regiment and served all over the globe. In 1881, 54th Foot was amalgamated with 39th Foot to become Dorset shire Regiment. In 1951, it was re-named Dorset Regiment. In 1958, it was amalgamated with Devonshire Regiment becoming Devonshire & Dorset Regiment. In 2005, it became Light Infantry and in 2007 First Battalion of The Rifles.

A year after raising, 54th Foot went to garrison Gibraltar and returned to Ireland in 1765 after a decade of overseas service. The regiment fought in the American War of Independence where it was part of Lord Cornwallis’s force. Major John Andre of 54th Foot opened secret negotiations with Benedict Arnold commanding American forces at West Point. He was captured when returning after one such rendezvous with details of all American forces in Arnold’s handwriting and was later hanged. 54th Foot fought in the battles of Brooklyn and New London. In the battle of Fort Griswold, they lost their commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Eyre. It burned the town of New London along with several prisoners thus earning the nick name of The Flamers. After the American war, the regiment moved to Canada and returned to England in 1791.

In 1801, the regiment sailed for Egypt and earned the battle honor of Marabout. It served several long tours at Gibraltar, West Indies and South Africa and was at Waterloo but didn’t participate in the battle. In 1820, the regiment landed at Madras to start its first long tour of duty in India. Cholera was raging in the presidency when the regiment landed, the first casualty was Sergeant Major Patrick Kelly. The regiment moved to Bangalore and remained there for four years. Peace time idleness had its own complications and four officers of the regiment died in duels. In 1824, the regiment was ordered to join the force getting ready for First Anglo-Burma war where regiment earned the battle honor of ‘Ava’. This was a trying campaign and disease took more toll than fighting. In December 1825, when regiment returned to Madras there were only enough fit men to escort regimental colors. There were two British regiments in the force; 54th and 44th and both suffered heavily from disease. This was the main reason that any plan of garrisoning European troops in Burma was abandoned. In 1840, regiment returned to England. During its stay in India, regiment lost thirty officers including three doctors.

The news of mutiny reached England in June 1857 and 54th was ordered to India. It sailed to India in August 1857 in three detachments. Headquarters section of the regiment along with commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Bowland Moffat and his family sailed in Sarah Sands. There was a major fire at the ship with the danger of powder and ammunition exploding and the troops worked tirelessly to put out the fire. The regimental colors were secured in a saloon where fire was raging. Regiment’s adjutant Lieutenant Houston and Lieutenant Hughes made the first attempt to secure the colors but failed due to fire and smoke. Ship’s Quarter Master Richard Richmond covered his face with a wet cloth and dashed to the saloon. He took the colors down but fainted. Private William Wiles ran after him and dragged him out as well as secured the colors. Damaged Sarah Sands limbered into the port of Mauritius.

Headquarters section finally made to Calcutta in January 1858 exhausted and short of supplies after another perilous journey. They had run out of tobacco. An American ship was anchored at Calcutta and an officer was sent to purchase tobacco from Americans. After hearing the story of their journey, the captain of the American ship gave them all his supply of tobacco but refused any compensation. The regiment thanked the Americans by sending firework rockets in the air and the band played Yankee Doodle. In 1858, various detachments of the regiment chased remaining rebel groups in Banaras, Azamgarh and Allahabad and Oudh. 54th lost more men from the weather than battle. In the month of May alone, fifty four soldiers of 54th died of heat stroke. From 1859 to 1865, the regiment was stationed at Bareilly, Fayzabad, Gorrackpor, Cawnpore and Calcutta. In 1866, it left for England. The nine year tour of India cost the regiment five officers and over three hundred and seventy dead and 350 invalided.

In October 1871, regiment sailed again for Bombay for its third tour of India. In 1872, during the rebellion of the kooka sect of Sikhs, 54th was rushed to Ludhiana. However, civil authorities with the help of local state troops of Maler Kotla had severely dealt with the trouble by blowing forty kookas from the guns. In the summer of 1872, regiment lost 30 men from cholera. 54th was stationed at Jullundur, Amritsar, Phillour, Morar, Calcutta, Salimgarh and Meerut, Roorkee and Cherat. In 1879, trouble started in Burma and regiment once again landed at Rangoon.

In 1881 regulations, 54th joined another regiment with special connection with India. 54th became 2nd Battalion of Dorset shire Regiment and 39th Regiment of Foot First Battalion of Dorset shire Regiment. 39th Foot was the first regiment to land in India in 1754 thus earning the title of primus in indis (First in India). On June 30, 1881, 54th Foot assembled for the last parade in memory of 54th and saluted their colors. In the evening in the officer’s mess, the punch bowl was filled for the last toast for 54th and regiment faded from the pages of history.

The story of 54th is typical of a British regiment of the era. European soldiers in India were divided into four different categories. First category was soldiers of fortune who started their career with local powers and after supremacy of East India Company (EIC), transferred their services to company army usually with irregular cavalry. Company army consisted of native and European establishments. Europeans were officers in native establishments although in early history some non-commissioned officers were also posted to native regiments. The third category was company’s European regiments where officers and privates were Europeans. The last category was British regiments stationed in India for a specified period of time usually from five to twenty years. To differentiate them from local forces prefix HMs was added to their numbers. In 1759, HMs 84th Regiment of Foot was raised specifically for service in India.

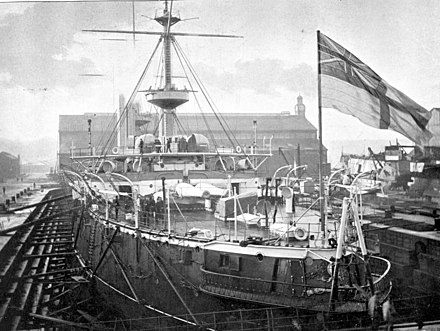

HMs regiments embarking for India maintained a small depot in barracks at Chatham. In eighteenth and early nineteenth century, travel from England to India took about six months and journey was hazardous. Many troop ships were lost on these journeys. HMs 91st Foot lost four hundred soldiers when their ship sank. Soldiers were as disciplined at the time of sinking as they were on parade. During the journey, when ship anchored at a port, soldiers were not allowed to disembark for the fear of desertion. Soldiers spent most of their time drinking, gambling, shooting at sea birds and fishing. The captain’s hands were full with court martials and awarding confinement and lashing. British soldiers landed at the ports of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta and marched inland to their cantonments. Before the rail days, the march was by foot. For each soldier there were 3-5 non-combatants and a whole native bazaar accompanied the regiment on the march.

In the early days, soldier’s barracks had no sanitation or water supply. There was no system of garbage removal and a flock of vultures around the barracks removed lot of waste and were nick named ‘adjutants’. There was endemic sickness and mortality rate was over ten percent from sickness during peacetime and climate and disease killed more European soldiers than combat. 50th Foot arrived in Calcutta in 1840 and lost twenty soldiers from Cholera in the first few months. After a brief trip to Burma, it came back only to lose eighty more men from Cholera. It moved to Cawnpore to escape the dreadful epidemic but lost additional sixty eight soldiers. In comparison, in the fierce battle of Punniar against Marhattas in December 1843, regiment only lost only eight men and one officer. HMs 3rd Light Dragoons landed in India in 1837 and the strength of the regiment was 420. In 1853 when it left for England, only forty seven of the original soldiers returned home. In the first five years in India, regiment lost eight officers and 168 men from sickness (seventy three in a single month of June 1838). Royal Northumberland Fusiliers lost 232 men from sickness during fourteen years stay in India.

Hot weather and the unpractical thick European outfit resulted in most uncomfortable situation for soldiers. The monsoon brought fever and sickness. Soldiers turned to drink to forget the harshness of the environment and the ever present danger of sudden death in the absence of combat. Many commanding officers punished drunkenness in the lines by ordering two parades a day. In hot weather, this aggravated the problem as thirsty and exhausted soldiers drank more and dying from heat stroke.

In general, the British army was an army of poor soldiers of lower social class commanded by rich aristocrats. Enlisted soldiers were poor and most joined the army to avoid starvation as they had no job while some joined to avoid prison for a criminal offence. Magistrates offered them to either go to the prison or serve the sovereign. Majority of soldiers were Irish and Scottish. British soldiers enlisted for life (usually a 25 years stint) before short service was introduced in 1874 and regiments served long tours overseas. Serving soldiers transferred to another regiment to stay in India when the tour of duty of their own regiment was up. HMs 16th Lancers spent twenty four years in India and in 1846 when regiment left for India, a large number of troopers (240) transferred to HMs 3rd Light Dragoons to stay in India. British soldiers and junior Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) were called British Other Ranks (BOR) and they came from poor families of lower socio-economic class. The life in India with all its hardships was still better for them compared to England. Many soldiers married local women and preferred to stay in India.

A very small numbers of wives were allowed to accompany the regiment on overseas duty. The only sexual outlet for young soldiers was to resort to the world’s oldest profession. Colonial authority obsessed with control and regulations closely supervised brothels. In 1850s, there were seventy five military districts and in every district prostitution was supervised by the authorities. All prostitutes were registered, minimum age for prostitutes was fifteen and women were provided with their own living quarters or tents that were regularly inspected. These bazaars were called ‘lal bazaars’ (red streets). Some establishments were quite large and a brothel in Lucknow had fifty five rooms. Prostitutes were regularly examined by European doctors and those infected with sexually transmitted diseases were removed and not allowed to practice their trade until recovered. Both native and European soldiers used these bazaars; however sepoys were discouraged to visit those prostitutes preferred by European soldiers. Most British soldiers were from lower strata of the society and were not held to the standard of a British officer. British soldiers visited prostitutes more often than sepoys. One reason was that British soldiers were not married while sepoys were usually married men. Both heterosexual and homosexual relations were common in mid nineteenth century. British regiments spent several years in India and many a times children were born of such relationships. Special houses and schools were assigned as early as eighteenth century for these children.

In the later part of nineteenth century, living conditions of British soldiers in India markedly improved. A number of soldiers after retirement also stayed in India and joined pensioner and invalid companies that performed some garrison duties. Others joined civilian occupations related to activities in military cantonment such as military contractors and became quite prosperous. Their pension enabled them to live much more comfortably in India, however, uprooted from their own culture, not allowed to mix with English of higher class in India and separated from teeming millions of Indians around them, they were isolated and a large number of them became alcoholics. The fate of those who returned to England depended on the strength of their family. If they had strong family network, they were able to adjust, marry and live a normal life. Those with no family network quickly spent their savings in drinking establishments and usually died on streets or in poor houses.

On 28 January 1948, the last British battalion 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry (old HMs 13th Light Infantry) embarked from Bombay thus drawing the curtain on two hundred years history of British presence in India.

We broke a King and

we built a road

A court house stands where

the reg’ment goed

And the river’s clean where

the raw blood flowed

When the widow give the party

Rudyard Kipling

Sources

• Records of the 54th West Norfolk Regiment (Roorkee: Thomasen Civil Engineering Press), 1881

• Richard Holmes. Sahib: The British Soldier in India (London: Harper Perennial), 2005

• The Keep Military Museum. http://www.keepmilitarymuseum.org/

• Hamid Hussain. Mangal Panday – Film, Fiction & Facts. Defence Journal, November 2012