Context

The results of Iran’s February 26, 2016, parliamentary and Assembly of Experts elections could prove to be an important turning point in the history of the Islamic Republic. Coming on the heels of the implementation of the nuclear deal, the election served as a referendum in favor of President Hassan Rouhani’s moderating approach to international affairs. What this means for the future of Iran’s relations with its Persian Gulf neighbors depends largely on the durability of the broad-based pro-Rouhani coalition and its ability to maintain the upper hand against hardline factions close to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, which prefer to keep Iranians in perpetual confrontation with the U.S. and its regional allies as a means of preserving the fervor of the Islamic revolution.

During the run-up to the Iranian elections, tensions were high between Iran and most of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. In January, hardline Iranian youths had set fire to the Saudi embassy in Tehran in retaliation for Saudi Arabia’s execution of the dissident Shi’ite cleric Sheikh Nimr Baqr al-Nimr. Saudi Arabia and Bahrain responded by severing diplomatic ties with Iran, while Qatar and Kuwait recalled their ambassadors and the UAE downgraded relations with Tehran. Oman was the only GCC member that did not take any diplomatic action against Iran.

The diplomatic spat occurred within a region already rife with sectarianism, fed in large part by the Saudi-Iranian cold war being waged throughout the Middle East. While the conflict is primarily geopolitical in nature — Iran and Saudi Arabia claim the mantle of leadership for the Shi’ite and Sunni communities, respectively — it has led to a hardening of sectarian identity among many of the regional players. This is especially the case with regard to the proxy war being fought in Syria between what many characterize as an Alawite-Shi’ite alliance, led by Iran, fighting against Sunni opposition forces backed by Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey. The Saudi war in Yemen also has sectarian overtones, with Riyadh justifying its intervention there as a means of countering the Houthis, whom it has long painted as Iranian proxies due to their Zaydi Shi’ite faith.

Meanwhile, with Iran emerging from years of sanctions, GCC leaders are concerned by what they see as U.S. naiveté regarding Tehran’s regional behavior.

Analysis

Iranian Foreign Policy Decision Making

To assess the potential impact that the election results could have on Iran’s foreign policy, it is necessary to understand the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy decision-making process. Although Supreme Leader Khamenei is the commander-in-chief and has veto authority over all decisions, he cannot simply dictate the outcome of policy disputes. This is because power in the Islamic Republic is dispersed among numerous factions connected through a multitude of political, familial, economic, and security networks. In order to maintain regime stability and to stay in power, Khamenei has had to balance the factions off of one another while also securing the interests of the most powerful among them.

Therefore, to pursue a consistent foreign policy strategy, Iran must achieve consensus among the various power centers. When this is not the case, Tehran can pursue contradictory ends. For instance, when hardliners became concerned in the early 2000s over the reformist President Mohammad Khatami’s “dialogue of civilizations”, which sought to moderate the Islamic Republic’s relations with the West, Khamenei undermined his efforts by pursuing parallel, hardline foreign policies through defense attachés abroad as well as cultural institutes attached to Iran’s embassies. Indeed, foreign policy disputes in Iran often revolve around factional competition rather than the specifics of the policies themselves. One striking example came in 2009, when reformists opposed President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s attempt to pursue a nuclear fuel swap deal, which would have eased tensions with the West, because they did not want the hardline president to benefit from such a landmark deal.

The Supreme Council on National Security (SCNS) serves as the clearinghouse for policy arguments throughout the system, and is the official arena in which elected officials can lobby for their preferred policies. Historically, Khamenei has gone along with most of the SCNS recommendations. Both the president and the speaker of parliament hold permanent seats in the SCNS, alongside the ministers of foreign affairs and intelligence, the judiciary chief, the leaders of the regular military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), and a representative of the supreme leader. Therefore, when the heads of the executive and legislative branches are aligned on the same side of an argument – as is currently the case – their voice is amplified. Moreover, during the run-up to the SCNS deliberations, the president and parliament have the capacity to issue public pronouncements, which can serve to shape public opinion and set the conditions within which a decision is made. It is important to note, however, that the IRGC and members of the supreme leader’s personal office are also able to lobby Khamenei directly, providing them with an advantage over the other SCNS members.

Today, the Islamic Republic establishment is divided into two camps with regard to foreign policy. Those aligned with President Rouhani believe that, above all, Iran must develop economically in order to regain its rightful place as a leader in the region. This means working to establish regional stability that can attract foreign investment. Others, including Khamenei, argue that Iran must prioritize resisting the West and pursuing economic self-sufficiency in order for the Islamic revolution to survive. They fear that, in the post-sanctions era of engagement with the outside, Iranians will lose their revolutionary fervor. For his part, Khamenei believes that youths’ interaction with the West will corrupt them. Rouhani, on the other hand, believes that preventing youths from interacting with the West will stymie technological development.

Election Results

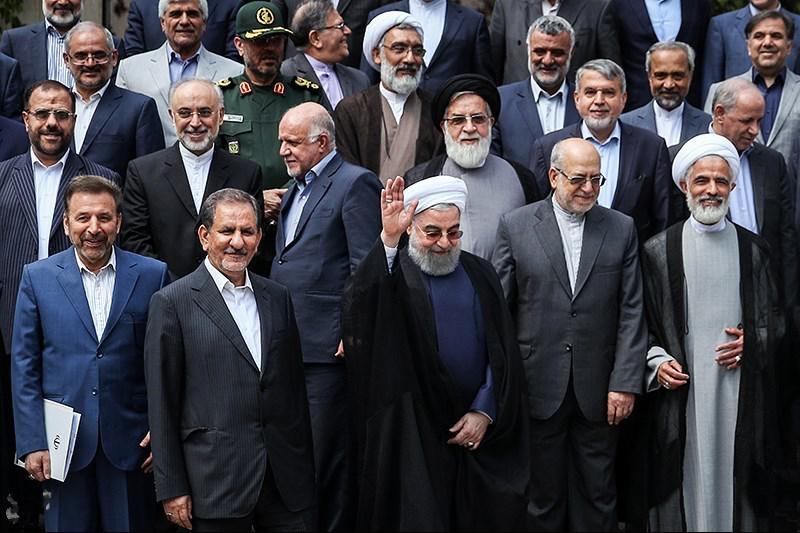

The results of the parliamentary and Assembly of Experts elections that took place on February 26 served as a public rebuke to Khamenei and other hardliners, and as a referendum in favor of Rouhani’s worldview.

Because Iran lacks formal political parties, each election is cause for new factional alliances, depending on the issues that are of highest national importance at that time. Furthermore, players within the regime look to election results to determine the nature of the current factional power balance. With the recent elections occurring shortly after the implementation of the nuclear deal, Iran’s path following the lifting of sanctions was the main issue at hand. This brought together an unlikely alliance of social conservative politicians with more reform-minded figures, who ran on a pro-Rouhani list, dubbed the List of Hope. Significantly for the president, the list won all of Tehran’s 30 seats, ousting a number of high-profile Rouhani adversaries, including Khamenei’s son-in-law Gholam Ali Haddad-Adel.

Tehran’s seats are important because members of parliament from the capital tend to play an outsized role in national debates compared to MPs from provinces, who tend to focus on local issues. One important Tehran MP to join the Rouhani alliance is Ali Motahari, the prominent son of a revered late ayatollah. Despite being a staunch social conservative, he has been supportive of the president. Of perhaps even greater importance has been the support of the pragmatic conservative parliament speaker from Qom, Ali Larijani, who hails from a prominent family that includes the judiciary chief. In the election, Larijani chose to run as an independent rather than join the conservative Principlist list, dominated by Rouhani’s opponents. Interestingly, Larijani received strong public backing from the IRGC Qods Force Chief Qassem Soleimani, who is tasked with implementing Iran’s military activities in Syria and Iraq. Soleimani’s backing of Larijani may indicate that he also supports Rouhani’s foreign policy approach.

The List of Hope’s success came despite efforts by Khamenei’s hardline allies in the Guardian Council to stack the deck against the moderates by disqualifying all but 30 of the 3,000 reformists who signed up as parliamentary candidates. Grassroots activism, including through social media, played an important role in uniting moderate voters around otherwise unattractive social conservatives. And while it is unclear whether the pro-Rouhani faction will have a definitive majority—59 of the 290 seats still must be decided by a run-off election because no candidate passed the 25 percent minimum threshold of votes to win outright—the president almost certainly will benefit from a less obstructionist parliament.

The List of Hope also did well in the Assembly of Experts election, with its candidates winning 15 of the 16 Tehran seats. Overall, candidates backed by the Rouhani coalition won 52 of the 88 available seats. This election may hold long-term importance if the assembly is tasked with selecting Khamenei’s replacement during its eight-year term. It is true that, despite its constitutional authority to select the supreme leader, the Assembly’s decision will be greatly influenced by outside players, especially the IRGC. However, the fact that prominent hardliners in the assembly were ousted and Rouhani himself gained a seat in the deliberating body has increased public expectations that the next leader will not be an extreme hardliner. Despite the government’s authoritarian nature, mass protests such as the 2009 Green Movement against President Ahmadinejad’s re-election have shown Iranian leaders that the public is still a force to be reckoned with.

Outlook

A pro-Rouhani coalition at the helm of Iran’s foreign policy decision making would bode well for Iran-GCC relations; in order to ensure economic development, Tehran would prize regional stability and constructive engagement with its neighbors.

This would include moderating official rhetoric, which impacts GCC leaders’ assessment of Iran’s intentions. In his first press conference after being elected in 2013, Rouhani referred to the Saudis as “our brothers”, and stressed the importance of good relations with the other Persian Gulf countries. At the Munich Security Conference in February 2016, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif stated Iran’s readiness to engage with the Saudis immediately, and called for a regional security agreement that would address common challenges. Zarif also reiterated that in a globalized world, attempts to arrive at zero-sum solutions are impossible. This is a far cry from statements by hardliners such as Tehran MP Alireza Zakani, who has boasted that “three Arab capitals [Damascus, Beirut, and Baghdad] have today ended up in the hands of Iran and belong to the Islamic Iranian revolution,” claiming that Sana’a would soon become the fourth. Zakani lost his re-election campaign to the List of Hope.

For constructive engagement to continue, however, the hardliners who want to prioritize exploiting instability in neighboring countries and propagating the Islamic Republic’s ideology—with whom Khamenei has an ideological affinity—must be counterbalanced by the pro-Rouhani coalition. There are three factors that could break up the President’s coalition: a domestic dispute over social issues or the economic windfalls of the post-sanctions era; GCC attempts at containment of Iran; and provocative actions from the U.S.

Pursuit of economic development is the primary issue uniting all the factions currently supporting Rouhani. If the President were to attempt to pursue substantive political reforms, he could lose the crucial support of some conservatives. At the same time, and although his approval rating stands at around 67 percent, Rouhani will feel pressure from the public to enact some change in the run-up to his 2017 re-election campaign. The President will also face the challenge of reforming the economy to make it more efficient and to attract foreign investment—a task likely to bring him into conflict with IRGC-affiliated companies that have done well due to lack of foreign competition as well as the quasi-private entities that control at least half of Iran’s GDP. Amidst the domestic infighting, it will be important to track the reaction of prominent conservative figures such as Larijani and Motahari. Their continued support for the president will indicate that he maintains a sufficient support base from among the various power networks.

The GCC’s overall reaction to Iran’s emergence from isolation is also likely to impact the factional balance within Iran. Attempts to contain the Islamic Republic could weaken the clout of Iranian politicians who advocate engagement. As the leading GCC power, Saudi Arabia’s actions will be influential. Officials in Riyadh are likely concerned that Iran will be able to entice other GCC countries with infrastructure development and technology cooperation agreements. Coinciding with Iran’s return from the cold, the kingdom is faced with the challenge of low oil prices and predictions that it will run out of financial reserves within five years. Iran, on the other hand, is better prepared to adapt to low prices because it has diversified away from oil to a greater extent. In the event of public agitation in response to austerity measures, the Saudi royal family could resort to painting Shi’ite protesters as agents of Iran in order to prevent Saudi Sunnis from joining them in the streets. Attacks on Saudi Shi’ites ultimately could force them, reluctantly, into Iran’s arms and would lead to a further deterioration in relations between Riyadh and Tehran. Meanwhile, Iraq could become another flashpoint, with the Saudis currently training upwards of 200,000 Saudi and allied forces to prepare for the possibility of clashes with Iranian-backed Iraqi militias.

Among the remaining GCC nations, there will be varying positions on how to engage Iran, shaped largely by each country’s ability to act independently of Saudi Arabia, the nature of each government’s relationship with its own Shi’ite citizens, and the level of potential business with Iran. Bahrain, for instance, likely will move in lock-step with the Saudis due to Manama’s heavy security reliance on Riyadh. The Sunni government in Bahrain has a long history of tensions with the island kingdom’s Shi’ite-majority population, and has accused Shi’ite protesters of being Iranian agents. Moreover, Bahrain’s Al Khalifa rulers have not forgotten a 1981 coup attempt that was backed by Tehran.

On the other end of the spectrum lies the Sultanate of Oman which, of all the GCC countries, charts the most independent path from the Saudis. Muscat has maintained cordial relations with Tehran throughout the history of the Islamic Republic, and played an essential role in facilitating backchannel U.S.-Iran talks that eventually led to the nuclear deal. Oman has also signed a USD 60 billion agreement that will have Iran replace Saudi Arabia as its largest supplier of natural gas. The direction the UAE takes will also be important. Dubai stands to benefit as a reshipment hub for the rejuvenated Iranian market. Abu Dhabi, however, has historically taken a more hardline stance toward Iran.

Finally, U.S. actions will have an impact on the balance of power in Iran. If sanctions removal is slow and Iranians fail to reap much economic benefit from the nuclear deal in the near future, it could weaken Rouhani and his allies in the run-up to his reelection. Furthermore, the U.S. Congress is intent on passing new sanctions on Iran over missile tests and human rights, which could also strengthen the voice of hardliners in Tehran. At the same time, if Iran’s reemergence is too fast, it could prompt fears among GCC leaders, in turn pressuring the U.S. to double down on containment efforts.

In the end, Iran and Saudi Arabia will remain rivals. Their differences over the U.S. presence in the region, leadership of the Muslim world, and Iran’s anti-monarchy stance are irreconcilable. However, if both countries prioritize economic development over geopolitical confrontation, it would go a long way in helping to stabilize the region. Other GCC countries can play an important role in bridging this divide.

A version of this article also appeared in Gulf State Analytics, an affiliate of POLITACT.