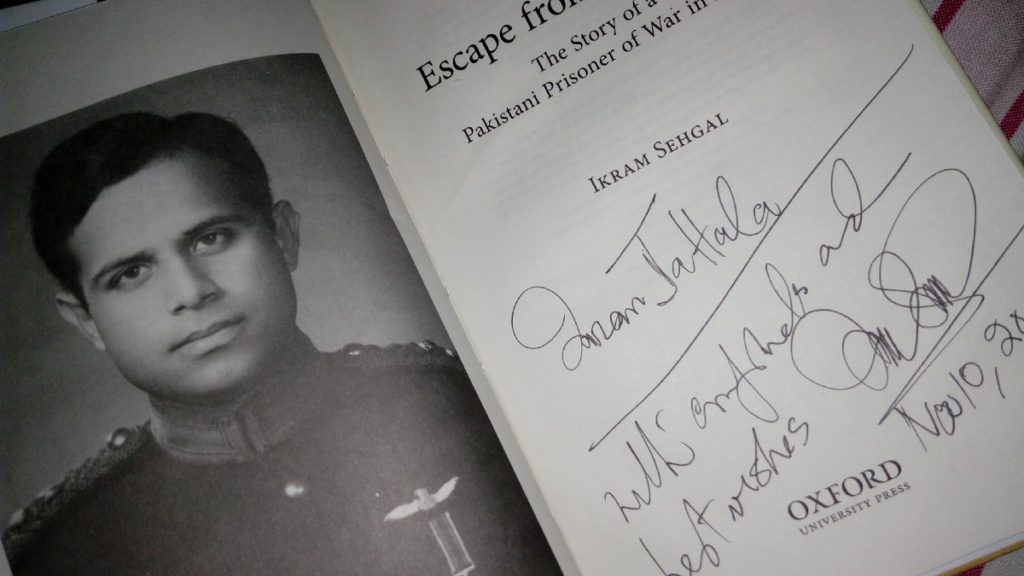

Ikram Sehgal, an articulate member of Pakistan’s strategic community, has been long time editor of the respected Defence Journal, representing the views principally of Pakistan’s military veterans. He earned his spurs as one of about twenty, by his count, prisoners of war of the 1971 conflict who made it back to Pakistan, of the forty or so who made it beyond the barbed wire. The ceasefire of the fortnight long war yielded up a PoW count of about 95000 (among them about 35000 regular servicemen from the Pakistan Army, PAF and PN alongwith 10000 from Frontier Corps, Rangers, Police and East Pakistan Civilian Armed Forces), the rest (50000) were dependants and civilians (civil bureaucracy personnel included). There was little incentive for most to attempt escape since the war was over and parleys for their return were under way. These eventuated in the agreement six months on in Simla, taking another year for their repatriation.

His story is singular in that his escape was not during or after the war, as is the case with most escapes, but prior to it. Its retelling is absorbing not only from the great adventure he recounts but from the little discussed facets of the prelude to the war he pro vides. Sensibly, the prologue is a recap of his breakout from a camp in Panagarh where he was detained. From Agartala to Panagarh he, alongwith other PoWs, was moved by an Indian Air Force Dakota on 25 April 1971. Sehgal characterizes Panagarh as a Prisoner of War (PoW) camp since retrospect indicated that the Indian Army was entrusted with operations in East Pakistan some time beginning late April. While there, for working out his escape, he pieced together information that suggested that it was run by 430 Field Company of 203 Army Engineer Regiment reporting to Brigadier Coelho as the Station Commander working directly under India’s Eastern Command at Calcutta (now Kolkata).

This indicates that while at the time of his incarceration and decamping, there was no declared war on, the levels of Indian military involvement, alongside that of political, intelligence and border guarding para military, was of the order of a ‘clandestine war (p. 134) However, needing to keep their involvement secret, since interference in internal affairs is prohibited in international law, Indians did not own up to their captives, leaves alone hand them back. This puts India’s record in observing the Geneva conventions under cloud. To sehgal since there was an internal armed conflict, on that had spilled over the border it was covered by universal Article 3 of the conventions and applicable for non-international armed conflict. His treatment by the BSF and Agartala jailers fell afoul of these, as did India’s opening of an undeclared PoW camp in Panagarh. How he gets there and what hap pens in the camp forms the first part of the ‘book and his escapades as he makes his way out of India form the remainder of the ‘un-put-downable ‘ book. Ikram Sehgal, a helicopter pilot, arrived on 27 March by a round-about route through Sri Lanka from West Pakistan for taking up his posting to the Logistics Flight at Dhaka (then Dacca). A month earlier the hijack of an Air India plane ‘Ganga’ to Lahore and its blowing up there had led to India cancelling over flights between Pakistan’s two wings. The episode in retrospect has the signature of an intelligence operation designed to make it difficult for Pakistan as the going got tough in its eastern wing. As it turned out, East Pakistan rose in revolt, a rebellion that had a profound emotional impact on sehgal, not quite twenty five then.

Born to a Bengali mother and a Punjabi father in his emotionally charge state, he opted while on ‘joining time’ to visit his erstwhile unit, 2E Bengal. 2E had revolted, fearing it was to be disarmed the following day. In doing so, it besmirched its record by murdering its West Pakistani brothers-in-arms and in the case of the subedar major, even his family. Since Sehgal’s father had raised the unit and Sehgal spent both his child hood and his subaltern days with the unit, it was regimental spirit that drew him to the unit in the troubled times. Welcomed back, he never the less threw the unit officers into a turmoil as to what to do with him, particularly since their revolt they were forming. Up as the core of the insurgency, covertly aided by India. His Bengali compatriots were deeply suspicious of his arrival and his older colleagues more nostalgic eventually, he was handed over through a ruse, to Indian 91 Border Security Force battalion. Tortured for information and on suspicion that he was a commando infiltrating the rebellion to find out more about it for Pakistani authorities, he was rescued by the Indian army that was at the time not involved in the sponsorship of the insurgency. Handed over to the civilian administration, he spent time in Agartala jail, only to eventually be clubbed with other West Pakistani servicemen handed over by the East Pakistan military units and carted off to where his story begins, Panagarh , a Second World War military station and one that today houses the headquarters of India’s Mountain Strike Corps.

As it turned out, getting out from the barbed wire to freedom was the easy part. Pepping him self-up with recall of his training days, he headed for Burdwan on foot. The word of his escape was out. He evaded his pursuers by hitching a ride to Calcutta with an elaborate cover story. His intent was to meet up with someone who had shared her address with him. Instead, he found a tailor shop. Thinking rapidly on his feet, he scouted the American consulate. Little did he know then that the Americans were beholden to Pakistan for patching them up with China? His bold telephone call to the consulate gained him respite, but not succor. The American’s not wanting a diplomatic incident on their hands outfitted him and let him go.

An aviator, he naturally gravitated to the airfield, aware that Indian security would be watching other escape routes, but might not think of covering the aerodrome. Off he flew to Delhi, managing there to contact Pakistan’s military attack. He was kept at a safe house and then dispatched in an undercover operation involving Pakistani agents and their Indian contacts, to Kathmandu. There he boarded a flight for Bangkok with two of his chaperones, managing to reach Dacca (now Dhaka) back finally after five months and 99 days of Indian captivity.

Though through this journey, Sehgal witnesses the worst of rebellion and faces torture, he does not lose his humanity. He understands what the context to the lives of those he encounters does to them and shapes their actions towards him. He comes face to face with his own mercurial personality, leveraging it for creative problem solving. That is the easy part. Implementing is made doubly difficult by fear, which Sehgal describes firmly as a constant companion. That he made it back is evidence he overcame it with aplomb, the signature of courage since courage is not about not feeling fear, but not taking its counsel. Besides an adventure story waiting to have a producer turn it into an action thriller, a significant issue the book deals with is of inter-ethnic tensions. His mixed parentage enabled him a unique vantage point, besides pitch-forking him into being the hero and eventual author of his own book. Suspicion continues to dog him when he returns to Pakistan. Facing hostility on joining his aviation squadron in West Pakistan on return, he opts for infantry. He recounts apprehensions of his new Commanding Officer Mohammad Taj, later brigadier holding reservations about Bengalis. Taj had been on intelligence staff in the Dacca garrison when the uprising took place on 25 March. Nevertheless, when the balloon went up, Taj Mohammad personally came round to sehgal’s company to make Sehgal a battle field Major for his showing in operations. Even Sehgal’s company senior Junior Commissioned Officer overcame – his prejudices, preferring ear retirement to serving on when Sehgal was dismissed from service under cloud for his days in India. the ultimate tribute, his war time company that his CO Taj had initially christened ‘Deserter company carries his name, Sehgal Company to this day!

What Sehgal manages to con vey is that people are all alike whereas the Bengali troop’s rebellion visited atrocities on W Pakistani and Bihari compatriots such as in Chittagong West Pakistanis were ruthless in putting down the rebellion. As one with: foot in both camps emotional Sehgal is aware of the good in both and the compulsions behind bad. It is to his credit that though witness to India’s doings in East Pakistan and the fact that it did own up to the Pakistani officers in its custody, he owes its military no more ill will than any self-regarding military man for a war time enemy with the empathy he brings to narration, he packs his adventures with a deep message of, humanity war, deserving of a wider South Asian imprint. It is insensible for the subcontinent to continue to have such youth as Ikram Sehgal’s younger self pitch themselves against each other in conflict. This review must end with Sehgal’s message: ‘Freedom from captivity is worth risking one’s life for.