Introduction

When the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (or SAARC) was created in 1985 – and the consensus was that it was the product of a Bangladesh initiative – it can be said to have been a triumph of hope over experience. Till then South Asia, or the Indo-Pak Subcontinent by which the region was known, was but a geographical expression. Not only did the component States lack any sense of cohesion, they were constantly at loggerheads with one another. Bitter wars were fought between India and Pakistan for instance, in 1947, in 1965 and 1971, the last resulting in the birth of Bangladesh as another independent entity. Nepal had a long history of love-hate relations with India, nestled between two major State protagonists in Asia, China and India. Bhutan and the Maldives were sovereign, true, but with no capacity to leave any footprint upon global inter-state relations. The seeds of intramural conflict were being sown in Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, that were eventually to develop into massive conflagrations. That was the regional matrix, when an idea first mooted in Dhaka, found fruition in the regional organization called SAARC, which was formally established in 1985.

The States of South Asia are a product of the Westphalian system, a political order that grew out of the Treaty in Europe bearing that name, entered upon in 1648. The Treaty of Westphalia envisaged co-existing sovereignties, with aggression held in check by mutually agreed norms and mores. In due course empires fragmented into nation states. The two horrendous conflicts of the first half of the twentieth century, brought to the fore the destructive nature of warfare, and gave an impetus to the process of decolonization. The countries of South Asia were a product of this phenomenon. Quaid e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s claim for Pakistan was based on a separate nationhood for Indian Muslims and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s demand for an independent Bangladesh was based on the argument that his people were distinct from the Pakistanis.

Theories Driving Regionalism

The end of World War 11 witnessed a surge towards regionalism. It was particularly perceptible in Europe, which led the way in this regard. Jean Monnet, the prophet of the European Iron and steel Community, the precursor of the modern-day European Union, and others of his ilk were anxious to leave behind the days of the traditional Anglo-French rivalry. The philosophical mentors of this process of integration were, broadly, two schools of thinkers: the ‘functionalists’ and the ‘neo-functionalists’. The ‘functionalists’, like David Mitrany, argued that complex technetronic developments had thrown up equally complex issues whose solutions needed to be handled by international agencies with tasks defined by the nature of these problems rather than by interest of governments.

The ‘neo-functionalists’ like Ernst Haas would go even further. They would hope that future technical agencies would so integrate States as to make them lose all the attributes of sovereignty. While influenced by these rationalizations, the small group of professionals in the Bangladesh Foreign Office who crafted the concept of South Asian regional cooperation, to which I myself made a small contribution, entertained far modest goals. It was their hope that linkages across a broad spectrum of activities would generate such a sense of collaboration as to lessen the intensity of differences on more central issues (Kashmir, river water distribution etc.). That was the essence of the letter that went out from Dhaka to the South Asian Heads of government in 1980. Eventually, following several rounds of meetings at senior levels, the first SAARC Summit was held in Dhaka in 1985.

Regionalism in South Asia

SAARC began tentatively, almost hesitatingly. Initial areas chosen for cooperation were innocuous ones, like postal services, tourism, shipping, etc. on which differences were minimal to start with. The organization was headquartered in Kathmandu, not the capital of any of the major protagonists, and not the most attractive locale for senior personnel to serve in. The Secretary General was to have the rank of only an Additional Secretary, a second tiered level among the bureaucracies of South Asia. The Council of Secretaries had for its member the Foreign Secretary, most often not the ranking official within the member-states, and not the Cabinet Secretary, the most senior and coordinating civil servant in those governments, as was the case with , say, the Commonwealth. Then there was the famous and infamous Article x of the SAARC Charter that forbade discussions on contentious bilateral issues and called for all decisions to be taken on the basis of unanimity. This pretty much rendered the organization a toothless talking shop.

Unsurprisingly, any progress, if at all, was made at less than at a snail’s pace. At least on eleven occasions the original schedules of the summits had to be altered. India- Pakistan disputes appeared to go on unabated. There were also other bilateral problems between Nepal and Bhutan, Bangladesh and Pakistan, Nepal and India, Maldives and Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka and India, and Afghanistan and Pakistan that continued to queer the pitch for cooperation relentlessly. Agreements on counterterrorism were honoured more in breach than in observance. India has an overwhelming physical presence in the region, and with the component states becoming increasingly assertive, even in foreign affairs, New Delhi’s role in formulating and executing a clear-cut external policy was being rendered increasingly complex. The Teesta water distribution between India and Bangladesh, and the ability of the West Bengal State government to thwart New Delhi’s plans is a case in point. A major aspiration of SAARC was to promote welfare and improve the quality of life of the people of the region by accelerating economic growth and enhancing regional trust among member states. At least at a stated level at each major event the point was made that peace and prosperity were indivisible and the region had a common and shared destiny for a better and brighter future. Yet SAARC left little positive impact on the 20% of the global populace that comprised the region, and whose combined GDP in Purchasing Power Parity terms amounted to US $ 9 trillion (2014 figures).

On the contrary, there was a regular war between India and Pakistan on Kargil in 1999. There were constant mutual accusations of state-sponsored cross-frontier terrorism. There was a South Asian Preferential Trading Arrangement signed in 1993 which entered into force in 1995. This turned out to be one of the least ambitious trading arrangements in the world. Though it provided for a positive list of trading items, trade in each of those could be regulated. Commitments on tariff reductions were entirely voluntary. There were no clarity on rules of origin and most significantly a Dispute Settlement Mechanism was lacking. Despite this slow progress, indeed because of it, attempt was made to create a Free Trade Area (SAFTA) in 2006, incorporating the instruments that were missing in SAPTA. In spite of it, intra-regional trade continued to remain below 5 % of the total trade of SAARC members. This amounted to a paltry US $40 billion, compared to US $1 trillion the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) countries in the same year (2011).While there was a commitment to reduce trade barriers, non-trade barriers (NTBs) remained high. Commercial intercourse between the two largest neighbours, India and Pakistan, did not exceed the sum of US $3 billion, not more than that which occurs illegally, or through Dubai. The concept of ‘sensitive list’ of trade items were introduced which assumed unhelpful lengths.

Analysis of Limited Success

SAARC’s poor performance can be attributed to several reasons. First, unlike in Europe where nation states were firmly established, and the matrix was appropriate for the ‘Union’, the boundaries in South Asia were of far more recent origin. In this region there existed an intellectual confusion whether the commonalities that bind the peoples or the distinctiveness that separates them must be stressed, whether East or West Punjabis, or East or West Bengalis, or Indian and Sri Lankan Tamils, or Madhesis and Biharis should see themselves as the same or distinct communities. ‘Regionalism’ would encourage the former, whereas the separate sovereignties would be justifiable by the latter.

Second was the permanence of the poor state of India-Pakistan bilateral relations. They seemed locked into perennial disputes, not only of irredentist nature-Kashmir, Siachen and Sir Creek for example, but across a broad range of political and diplomatic issues, usually preferring to line up on opposite side on any contested subject. Both had acquired nuclear capabilities, developed deterrence postures vis-à-vis each other, but could not succeed in building the kind of détente that superpower rivals like the United States and the Soviet Union had done during the Cold War era. Pakistan resisted India’s aspiration for a permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council and India was not unhappy over Pakistan’s expulsion from the Commonwealth (in 2008). Whether over Kashmir or cricket, the two behaved as eternal rivals. There are of course glimmers of hope from time to time, such as the impromptu Modi visit to Pakistan last December, but there are often quickly eroded by contrarian incidents, such as the raid in Pathankot that led to the deferment of the Foreign Secretary-level talk.

Third, the operational/functional method of SAARC has been unhelpful. Unlike in most regional organizations where negotiations are held at two levels, senior officials and political, in SAARC there are two distinct levels of bureaucrats-Directors General (Planning Committee) and Foreign Secretaries (Secretaries Committee), before documents are presented to Foreign Ministers and thereafter to the Heads of Government. Issues are often determined at Secretaries’ level, the Directors General having cleared (or not cleared, as sometimes might be the case) those at the first instance. Consequently the hands of the Ministers and the Heads are usually tied by the time they examine the agenda. By training and tradition, South Asian bureaucrats tend to be conservative and crusted which leaves the political masters in this bottom-up approach with very little room to manoeuvre.

Finally, the SAARC Charter itself, Article X (2) for instance which precluded discussions on contentious bilateral issues structurally impeded any substantive deliberations. Only ‘low hanging fruits’ could be addressed, and, alas, there are not many of them of any significance in relations among the South Asian nations. The Secretariat was not trusted by the member states enough to represent their interests. For instance the SAARC Secretary General rarely spoke on behalf of the member countries of the organization in such international forum as the United Nations. SAARC countries were usually chary of allowing the Secretary General to initiate dialogues with external actors. He or she was seen as the Secretary General of the SAARC Secretariat, rather than of SAARC as an organization.

The Positive Aspects

This is not to say SAARC has not had any contribution in widening and deepening intramural relations among the regional countries. It has done so in many ways. First, it has provided a platform for bureaucratic and political leaders, as well as those of South Asian vibrant civil societies including media personalities to come together. Second, there have been a number of important understandings across cross-cutting thematic issues as on drugs, terrorism, climate change, transportation, energy and the social charter. Third, some institutions furthering aspirations for common public good such as food and Development Banks, and the SAARC University have been set up. Finally, it has accorded the peoples of the region a sense of South Asian identity – much more than a mere description of his or her being a Subcontinental. This has, in turn, impacted positively in creating linkages, social and psychological, among the very large South Asian diaspora.

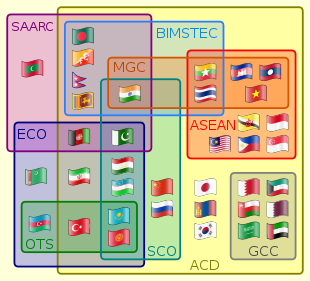

These are sufficient reasons to allow SAARC to continue to exist. However, it is obvious that certain actions are warranted to revamp, re-orient and retool SAARC in order to reorganize it in a way to be better able to achieve its objectives. This can be done, albeit partially, by undertaking certain steps pertaining to the structure and functions of SAARC. India, given its preponderance of size, strength and resources should be in a position to shoulder a disproportionate responsibility. It must be able to play the role of an ‘elder’ rather than a ‘big’ brother, something akin to how Germany behaves in the European Union. This is of course, easier said than done, because New Delhi would be constrained in myriad ways. Article X should be amended, but given the existing political climate, it would be well- nigh impossible to tinker with the original Charter. SAARC should allow for, and encourage other sub-regional groupings within its broad framework, such as BBIN (comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal)-which is happening in any case on the principle that one must let go to keep- but an argument could be made that this could weaken SAARC. Yet the aim should be to buttress, because it has such obvious uses. How can this aim be achieved?

Octagonal-ism: A New Paradigm

An answer could lie with what the author would term: ‘Octagonal-ism’, a loose and informal collaboration of the Heads of government of the eight countries. This eight-body interrelationship would comprise South Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, which is also co-terminus with the membership of SAARC. The leaders would work to evolve a ‘strategic partnership’ among their countries. A ‘strategic partnership’ would be distinguishable from the more formal ‘classical alliance’. The ‘strategic partnership’ would be designed to increase the power of states in absolute terms. In this sense it would be different from a ‘classical alliance’ which is ‘security –oriented’, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and even from political and economic integration processes (such as the European Union (EU), the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the African Union (AU). Another significant difference would be that, while a ‘classical alliance’ would normally seek a balance of power against a perceived adversary, a ‘strategic partnership’ would not be directed against a common rival, but instead would aim at a general accretion of influence. Also, while security pacts and political integration tend to surrender a portion of sovereignty in the form of sacrificing an element of decision-making powers on national defence, monetary and fiscal policies, a ‘strategic partnership’, on the other-hand, is based upon the mutual goal of increasing individual power and independence, thus allowing for the preservation of national sovereignty.

This is exactly why this ‘octagonal-ism, or a ‘club of eight leaders’ is more likely to succeed in forging a political entente than SAARC. The latter is a formal structure in which the fear of erosion of sovereignty precludes substantive discussions of a serious nature. That is indeed why the initial agreement or charter excluded contentious bilateral subjects from the agenda. That, in turn, led to a ‘catch 22’ situation, because as long as those intractable problems characterized mutual relations, progress on even functional areas were rendered difficult. ‘Octagonal-ism’ would not shy away from addressing such issues.

This forum would also afford the regional leaderships to discuss, understand, and if possible evolve similar positions on transnational, thematic issues such as climate change and terrorism, Global political milieu is in rapid change. The migration crisis in Europe, the failed ‘Arab Spring’ in the Middle East, the slow-down in the Chinese economy, the changes in how Japan acts in the global scene and shifts in the emphases in American policy, counter-terrorism strategies adopted by governments, all have a bearing on South Asia. Its leaders, and consequently, their countries, would benefit from a detached reflection in a collective informal format on these matters.

Take counter-terrorism strategies adopted by governments. In the world today deviant forms of Islam containing distortions of original tenets, are said to be a major breeding ground of violent extremism, including terrorism. Four countries in the region have a Muslim majority in their populations: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Maldives. India, with over 15 % of its 1.2 billion people contains the second-largest number of Muslims than any other nation–State in the world (just after Indonesia). The social fabric of many of these countries are threatened to be torn apart by extremist thought and actions. South Asia was also where Islamic philosophical schools as ‘Sufism’ and ‘Deobandism’ took roots. The former represents liberal syncretism and the latter is less akin to the extremist ‘Salafism’ and ‘Wahabism’ of the Middle East, which is not always known in that light. The eight leaders can informally deliberate on how the tolerant South Asian version of Islam can be used to counter radicalism, an intellectual and policy exercise that could be better conducted in less formal settings.

While the concept of this informal ‘Club of Eight’ would imply cutting down on bureaucratic red-tape and an overload of staff –work, one intellectual exercise would be helpful. That would be the creation of a ‘matrix’ dividing bilateral issues into categories: ‘green’, ‘orange’ and ‘red’ box issues, depending on the level of their complexity. The normal predilection would then be to initially focus on the ‘green’ box, then graduating thereafter to the ‘orange’ and ‘red’ boxes. If forward movement could be achieved on the simpler issues, it would be hoped that the resultant generation of goodwill would positively impact on the resolution of other disputes. While every issue would not involve all, all could informally bring to bear empathetically their minds on all issues. So rather than begin with Directors General or Joint Secretaries and then moving up to the level of heads, the process would begin with the heads and travel down below as directives. This would be a ‘top-down’ approach, rather than the ‘bottom-up’ as in SAARC. The idea would not be to supplant SAARC, but to further strengthen it.

Conclusion

The great lurking danger in South Asia is that as the rest of the world moves ahead, South Asia will run the risk of being left behind. This would happen if the world is changing, as it is, and South Asia is unable to change with it. The peoples of the region deserve much more, and the leaderships must be proactive in delivering what they deserve.

If there is a hill to climb for us, waiting will not make it any smaller. The time for action is now. As the Bengali poet, the mighty Rabindranath Tagore once said, if you wish to cross the sea, it would not do just to merely stand at its edge and gaze at the waters!