Prelude to Big Dams in Pakistan

The story of big dams in Pakistan has its beginning in the historic Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) accord that was signed in 1960 by India and Pakistan on the water sharing formula of the five major rivers that originate in the Tibetan Plateau/India and flow through the Indian territory before entering Pakistan, making the latter the lower riparian. The accord was midwifed by the World Bank (WB) and among the numerous accords and treaties signed between the two warring nations, IWT is the only one which has so far stood the test of time (minor infringements notwithstanding) even when the two nations were at war.

Pakistan won its independence in 1947 and its western wing (known as West Pakistan then) comprised the provinces of NWFP (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), West Punjab (now Punjab), Balochistan and Sindh. The state of Kashmir which was adjacent to the area designated as West Pakistan by the Boundary Commission of India had an overwhelming Muslim majority and based on the principles that governed the partition of British India into two sovereign states, Kashmir should have been an integral part of Pakistan’s western wing. Through chicanery India was able to absorb the entire state of Kashmir into its domain.

Pakistan protested vehemently and even initiated a limited military campaign in 1947 to win back the territory usurped by India. About a third of Kashmir was liberated by the Pakistani forces before a ceasefire was declared after India offered to refer the matter to the United Nations for arbitration. UN Resolution 47 adopted in 1948 decreed the holding of a plebiscite in the state to determine whether it wanted to be a part of Pakistan or India. Unfortunately despite passage of nearly seven decades no plebiscite has been held as India refuses point blank to honour its commitment and the unresolved Kashmir issue remains a major thorn that has bedevilled relationship between the neighbours and was the principal factor that led to the 1965 India – Pakistan War, the Kargil Conflict, the ongoing Siachen battle and the water dispute.

The loss of a substantial portion of Kashmir (referred to as Indian Held Kashmir or IHK by Pakistan) to India was a major factor that led to the signing of IWT by Pakistan. Five key rivers, Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi and Sutlej that are water lifeline for Pakistan originate from the Tibetan Plateau (Indus and Sutlej), the Pir Panjal Range in the Indian Held Kashmir (Jhelum) and the state of Himachal Pradesh (Chenab and Ravi) and traverse through India and/or IHK before entering Pakistan.1 With IHK under Indian control and East Punjab their legitimate domain, Pakistan remained at the mercy of their largesse because India as the upper riparian had the ability to turn the tap off the four key rivers (Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi and Sutlej) that flow into Pakistan that could practically turn it into a veritable desert. This huge disadvantage had to be neutralized if the future progress and survival of Pakistan was to be guaranteed. IWT was a way forward.

The World Bank divided the Indus Basin into two sub-basins – the Eastern sub-basin comprising basins of Sutlej, Bias and Ravi rivers, and the Western sub-basin comprising the basins of Indus, Jhelum and Chenab rivers. There was, however, a problem: territorially speaking the Eastern sub-basin was under Indian occupation, and therefore, the hydrological rights and territorial coverage were in accord with each-other. In case of the Western sub-basin, the rivers comprising it originated outside Pakistan – the Indus in China while the other two – Jhelum and Chenab in the Indian Held Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh province of India respectively. Indian hydrological rights of the Eastern sub-basin were problem free because of occupation of the Eastern sub-basin by India. Pakistan did not occupy the whole of the Western sub-basin, as a part of it was located in the Indian occupied Kashmir. Pakistan’s claim to the entire water system in the Western Basin was subject to its ability to utilise it gainfully which it could achieve only by building dams and reservoirs within Pakistan, committing that water. Pakistan’s failure to do so would weaken in quantitative terms its water rights of the Western Basin.2

According to unconfirmed reports when the President of the World Bank met with the Pakistani President Ayub Khan on the subject of IWT, he had made the following remark: “Mr. President, if you can fight a war with India on this issue and win it, I would not advise you to sign this deal but if you cannot do that this is the best deal you can have.”3 After much deliberation and debate, Ayub Khan accepted the proposal and the treaty was signed.

To the critics who blamed Ayub Khan for bartering away much of water to India without getting adequate return, he answered by asking if they could show him a better option. To the extent he was right because without the IWT accord Pakistan would have remained at the mercy of India where the latter could divert as much water from all the six rivers as it pleased. The only options for Pakistan would then have been to declare war on India which militarily enjoyed marked numerical superiority; to accept desertification of its territory or to re-join the Indian union on their terms. Under the circumstances, the ITW accord was and still is the best guarantor of ensuring Pakistani water rights as the lower riparian is not violated, provided it implemented steps that would make it almost impossible for India to take advantage of the legal loopholes in the accord to obstruct the flow of water from the three western rivers.

The World Bank had advised Pakistan that while the accord gives the entire water of the three western rivers to Pakistan its failure to utilise the waters gainfully could provide an opportunity to India to justify building of power generation dams on these rivers that could adversely alter their normal flow. Pakistan must, therefore, build major multipurpose storage dams which would also generate cheap electricity for the nation. Following the IWT accord the World Bank initially mandated the construction of Mangla Dam on River Jhelum. The dual purpose mega project Mangla Dam, one of the largest earth filled dams, began in 1960 and completed with technical and financial assistance of the World Bank in 1967. WAPDA in the meanwhile asked the World Bank’s opinion on future dams the country needed. The World Bank recommended the building of a dam at Kalabagh followed by one in Tarbela. WAPDA argued that Tarbela Dam should be made before the one at Kalabagh because the former was bigger, costlier, would produce more power and store more water than Kalabagh and technical assistance and finances were available for the project. Kalabagh was relatively simpler to construct and after the experience of Tarbela, WAPDA should be able to make it with minimum assistance of the world body. WAPDA’s views prevailed and work on Tarbela commenced in 1967 and the dam was made operational by 1977.

While the work on Mangla Dam was still in progress, WAPDA became concerned about the timeframe for which the benefit of electricity and irrigation water made available by these dams would suffice. In their assessment more dams of similar nature would become necessary, given the additional demand that would be generated by the increasing population. Ayub Khan during his visit to Washington in November 1963 explained WAPDA’s concern and requested the World Bank to prepare a post Tarbela development map for Pakistan. As a result the Indus Basin Study was initiated in 1963 by the WB and its report was submitted to Pakistan in 1967. Singularly very detailed, the study was one of the most comprehensive exercises ever undertaken by the World Bank for a river basin. In the words of the Bank, “it will serve as an indispensable model for engineers, economists and planners for years to come.”4 The report recommended construction of Kalabagh Dam after the completion of Tarbela and the benefit streams of the two dams (power, water, flood control) should be sufficient up to 1990. It further recommended that given the high rate of progress Pakistan was achieving then where its economy was dubbed as the Asian Tiger, dams upstream of Tarbela preferably one at Diamer Bhasha would be required beyond 1990.5 On the basis of the Indus Basin Study report, WAPDA mobilised and planned for the construction of the Kalabagh Dam to be completed by 1994 and Bhasha Dam by 2010. Unfortunately WAPDA’s recommendations never materialised6 and if it had, the acute power crisis and severe water shortage being currently faced by the country would have been avoided, besides considerably lessening the severity of recurring floods down-stream of Kalabagh.

Political Inertia Delays the Start of KBD: Controversies against the Dam Surfaces

Unfortunately for the nation after completion of the Tarbela Dam the leadership and its people lost focus and dam building was relegated to a very low priority and by the time the realisation finally dawned that dams on River Indus was an inescapable need of the nation, the KBD was mired in controversies that so far appear almost impossible to resolve. The failure of Pakistan to build power and water storage dams on River Indus has deprived the nation of cheap affordable hydel power generated electricity that does not pollute the atmosphere, stunted the agriculture growth in the country because of water shortage and subjected it to devastating floods that occur periodically playing havoc with life, property and economy of the nation.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) and his party, the PPP was in power from 1972 to 1977. Tarbela Dam whose construction was started in 1967 was finally completed in 1976 and the work on Kalabagh Dam should have started in 1977. Before Bhutto was ousted in a military coup by Zia ul Haq, he had reportedly ordered to start work on the Kalabagh Dam and complete the project on a fast track.7

Zia ul Haq, the military dictator had usurped power from ZAB and ruled the country with an iron fist for the next eleven years and his failure to build KBD cannot be condoned. True, he was occupied in his efforts to legitimize his unconstitutional takeover, deeply involved with the USA in expelling the Soviet forces from Afghanistan and propagate his version of Islam. It would also be correct to point out that in the 1980s the combined Tarbela/ Mangla hydel generated electric power output along with the availability of cheap gas to produce electricity at an affordable cost, power shortage was not an issue and did not figure high in the priority of the government. The World Bank, however, had warned that by the turn of the century Pakistan’s power and water needs would burgeon to an extent where KBD and other multipurpose dams upstream of Tarbela in the River Indus would become inescapable. WAPDA had establish the Directorate of Kalabagh Dam Project earlier and Dr. Shams ul Mulk on his return from duties abroad took over as the General Manager/Project Director of the KBD Project in 1987 but by then opposition to the dam had grown substantially. Two years later he was transferred on promotion as Member/Managing Director Water, WAPDA.

Zia ul Haq had the necessary power and authority to override the objections to KBD and build the dam. His failure to do so besides exposing his lack of vision and statesmanship has cost the nation dearly.

The first sign of opposition to KBD surfaced in 1982. In 1929 Nowshera and its adjoining areas in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province had suffered a devastating flood and WAPDA commissioned a study in 1982 to mark the areas that were most severely affected so that necessary flood protection embankments could be built to prevent similar disaster if the floods of 1929 was to recur. Watermarks were painted at the levels where the flood water had risen. Subsequent development confirmed a specific interest to create mischief and the word spread that the watermarks indicated the level groundwater would rise if KBD was constructed thus water logging the fertile lands of Nowshera and Swabi making them unfit for cultivation.8 The Awami National Party (ANP) under the leadership of Ghaffar Khan aka the frontier Gandhi, and his son Wali Khan latched on to this aspect and began a major campaign against KBD.9

Despite clarifications from WAPDA that the watermarks did not indicate the groundwater levels that would occur if KBD was built, the opposition did not abate and continued to snowball. The fact that the water level of the KBD reservoir even when filled to capacity was lower than the heights of Nowshera and Swabi and water does not flow upstream failed to convince the ANP. WAPDA’s efforts to redesign and lower the height of the dam to allay any fears of water logging only heightened their suspicion about the danger of losing precious agriculture lands in the province. With the ANP already up in arms against the KBD, serious objections to the dam project were also being voiced in Sindh. Their opposition to KBD was predicated on a number of factors, some technical and some political, these will be dealt with subsequently.

Democracy returned to Pakistan in 1988 and lasted until 1999, during this eleven year period Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif were alternately in power but neither had the vision or courage to untangle the opposition to KBD which solidified further. Musharraf overthrew the government of Nawaz Sharif in 1999 and for the next three years was given the mandate by the Supreme Court to rule the country singlehandedly. He too failed to overcome the resistance to KBD by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh and by then Balochistan had also joined the opposition bandwagon. Now only the province of Punjab was in favour of the dam while the other three opposed it tooth and nail. Musharraf did realise that KBD was critical to the future of Pakistan but could do little to advance its cause. As an alternate under his rule preliminary work on construction of Diamer Bhasha Dam, upstream of Tarbela was initiated.

Seven years have elapsed since the departure of Musharraf and during the five years of the PPP rule under Zardari the three provinces unanimously passed resolutions in their respective assemblies outrightly rejecting the KBD. Work on Bhasha Dam has continued albeit at a snail’s pace since then but experts agree that while Bhasha Dam has now become a necessity, without KBD Pakistan will not be able to realise the true potential of River Indus in provision of water for agriculture, generation of cheap and environmental friendly power generation and flood protection. Besides, the inability of Pakistan to harness and utilise the river waters allowed India to justify building of power generation dams on the three western rivers whose waters exclusively were allotted to Pakistan under the IWT.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Opposition to the Kalabagh Dam

The opposition to the KBD in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa primarily stems from the Awami National Party (ANP) that was founded by the late Ghaffar Khan and is currently headed by his grandson, Asfandyar Wali Khan. ANP was in power in the province from 2008 to 2013 and during their reign a bill rejecting the KBD was unanimously passed by the provincial assembly. To that extent Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s opposition to the dam may be justified though critics are quick to point out that the ANP received a mere 5% of total votes in the provincial elections even in 200810, hence it cannot be said to truly represent the voice of the people in the province. Pakistan Tehreek Insaf (PTI) under the charismatic Imran Khan is currently heading a coalition government in the province along with Jamat-e-Islami (JI) and a few other minor parties. While Imran Khan has periodically issued statements in favour of the KBD, his ruling coalition has not yet tabled a motion in the provincial assembly overturning the earlier one that had rejected the KBD. Perhaps they fear that any support to the KBD project might be portrayed by ANP as a betrayal of the Pashtun cause resulting in loss of public support for their party in the province.

ANP’s objections to the KBD is based on two pillars: one, the dam would further exacerbate the recurring floods on River Kabul and two, the construction of the dam would raise the ground water levels at Nowshera and Swabi to an extent where fertile plains would be rendered barren due to water logging and salinity issues.

As mentioned earlier, the rumours of Nowshera getting submerged by flood waters and the rise of groundwater to a dangerous level had its beginning in 1982 when wall chalking marks meant to estimate the level flood water had risen in the 1929 floods was assumed to be the level water would rise if the KBD reservoir was made. Many suspect the misinformation was deliberately fed to the then ANP doyen, Ghaffar Khan who publicly voiced his strong opposition and reservations on KBD.

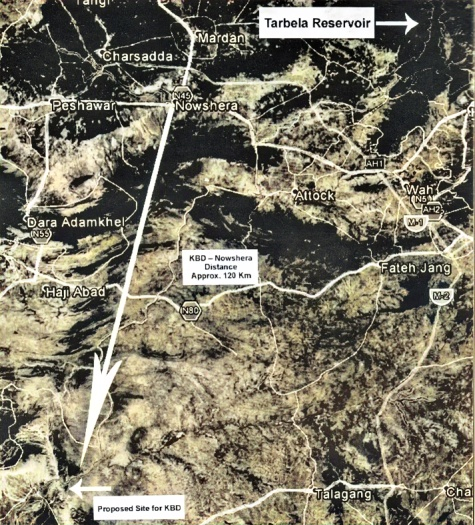

About KBD aggravating the Kabul floods, the statement is untrue. The confluence of River Kabul and River Indus occurs at Khairabad, a site close to the Attock Fort where the Indus river is about 4 to 5 Kms wide and the two then pass through a very narrow gorge (aka the Indus Gorge), barely 800 feet (20.5 metres) wide before re-emerging in the Kalabagh district. When Kabul is in high floods, the Indus Gorge becomes a bottleneck and the resultant backlash is the primary cause of the flooding of the River Kabul. The 1929 Nowshera floods were traced to this phenomenon when there was no KBD and this prognosis was reaffirmed in the 2010 super floods. KBD site which would be 120 Kms downstream of the Indus Gorge hence has no bearing to the flooding of Nowshera and its surrounding areas by River Kabul.

On the subject of the rise in groundwater level in Nowshera and Swabi, it has been repeatedly pointed out to the party that at its highest level KBD reservoir when filled to capacity would be 915 feet above mean sea level and the state it remains filled to the brim normally lasts for less than two months in a year. Even when the water touches the maximum height of the dam, Nowshera and Swabi would still be at a higher level than the water level in the reservoir. Unless the laws of physics are altered, the likelihood of Nowshera and Swabi getting waterlogged because of Kalabagh Dam is practically zero.

Despite repeated clarifications, briefings and presentations by eminent engineers and experts on large dams some of who were blue-blooded Pashtuns, ANP has not budged from its stance. In private a few of the present party stalwarts concede that their fear of Nowshera drowning and/or becoming waterlogged if KBD is constructed is unjustified but because a leader of the stature of Ghaffar Khan had opposed the dam unless his current successor Asfandyar Wali Khan takes it back, they are helpless.11 A sitting senator from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa did concede in confidence that opposition to KBD was unfounded but lamented that any alteration in their stance could sound the death knell for the party. When asked if his party’s interest supersedes those of Pakistan, he had no answer.12 A matriarch of the party is reported to have quipped that the federal governments should go ahead and start construction of KBD – her party would have no option but to protest publicly against it for about six months, perhaps even court jail sentences but the sky would not fall and the dam would be built without the loss of face of the party.13

To sum up, ANP’s basis for rejection of KBD project holds no water (pun intended) but unfortunately political expediencies prevent the party from reviewing its stance.

Sindh’s Objections to the Kalabagh Dam Project

Compared to the resistance from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa on KBD, Sindh’s opposition is far more contentious and would be more difficult to overcome. In the former the challenge to KBD is mounted mainly by the ANP, which is in a minority in the province; in Sindh the PPP which commands a majority in the assembly totally rejects KBD to an extent where it even refuses to debate the issue calling it a closed subject. The small nationalist parties in the province display even greater animosity towards KBD and in combination with the PPP they present a formidable opposition. The MQM, which is the fourth largest party in the country and has a stranglehold over Karachi’s electorate while enjoying a significant share of votes in other urban centres of the province has so far displayed ambivalence towards the controversy. They have no axe to grind on KBD but for the sake of provincial harmony and the fear of being labelled anti Sindh, votes against it whenever a resolution rejecting the dam is tabled by the PPP.

The objections of the PPP are varied and could be classified under four categories: ecological, technical, political and psychological. They need to be analysed rationally to determine their validity.

Ecological Impact of Kalabagh Dam on the Province of Sindh

Ecologically the PPP and the opponents of KBD argue that a dam of the size of KBD on River Indus will play havoc with the ecology of the entire region and Sindh will have to bear the ultimate cost. The loss of the three eastern rivers plus Tarbela and Mangla Dams along with their link canals have already reduced the mighty Indus to a mere trickle during the lean period and another large dam on the river will decrease it even further. They point out that the water that eventually makes it to the Arabian Sea through the Indus Delta should not be considered a waste of water because it helps maintain a delicate ecological balance in the Delta region and prevents the sea from further inland incursions.

Much of the Delta region where precious mangroves thrive has already been devastated due to sea incursions as a result of earlier damming of the river. These mangroves play a key role in reducing the fury of tropical storms/cyclones and protecting precious lands from being reduced to wasteland because of sea water invasion. The mangroves also provide a haven for shrimps and prawns besides other sea creatures and any assault on them will negatively impact the fishermen in the delta whose livelihood depend on fishing. The reduced amount of fresh water that currently flows into the Arabian Sea is barely enough for the remaining mangroves to survive and any further reduction could result in their total destruction which would play havoc in the lives and property of the people residing in the delta. And finally they point out that the normal flooding of the river during the wet season is a boon for a vast area along the river bank known as the Kachho. The annual flooding brings in rich soil that make the Kachho fertile and a large number of people along the river banks depend solely on the cultivation of these lands for their survival. Once Kalabagh Dam reservoir is operational the annual flooding will be further reduced and much of the Kachho lands would no longer be cultivable creating a major crisis in the province.

There is a human cost as well because large dams displace a number of people who have to vacate their ancestral abodes and have to be provided an alternate. Pakistan’s experience of Mangla and Tarbela indicate that the process is complicated, expensive, long drawn and tedious. For the KBD, however, the burden of population relocation would fall primarily on the Punjab province with the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province sharing a small portion, while Sindh will not be affected at all. Since Punjab is willing to bear the cost and burden of the population shift this aspect should not be listed as a factor in the litany of objections Sindh has against the KBD.

The KBD opponents point out that in USA and other advanced nations there is a moratorium on big dams and the older ones are being decommissioned. This statement is partly true – yes, the environmentalists there oppose large dams and a few have been dismantled but even today USA has about 75,000 dams of which about 8,100 are major ones that are still operational and despite the protests of a few, these will not be decommissioned any time soon.

Can a severely resource constraint nation like Pakistan afford to ignore the rich hydel potential nature has gifted it? Small dams and run of the river power plants on rivers and large canals is an alternate but it would require over 750 small dams of 8000 acre feet capacity to equal the storage capacity of one Kalabagh Dam which will also generate 3600 Megawatts of electricity.

Pakistan should compare itself with its two immediate neighbours, China and India as the three nations live under the shadow of the mighty Himalayas. China has over 22,500 dams and continue to build new ones while India has crossed the 4,500 mark and many others are in the pipeline – on the other hand according to the International Commission on Large Dams, total dams and reservoirs over the height of 15 metres in Pakistan are only 150,14 of which only two, Tarbela and Mangla classify as large dams.

The ecological observations of the critics of KBD are valid – in fact any human development in the shape of towns/cities/ road infrastructure etc. hurt the ecology to various degree. There is, therefore, an ecological price to be paid when a large dam is raised on a major river: fish and other aquatic wildlife including birds that depend on the flow of the river downstream of the dam would be disturbed. The reduced flow of fresh water through the river delta would affect the natural balance and some species of plants/trees and wildlife would be adversely affected. These losses should be measured by the gains that would accrue by its construction and the decision to go ahead with the dam should only be taken if the former significantly outweigh the latter.

Large dams built for power generation is a source of power at a very affordable rate. Yes, they are capital intensive but if the funds are made available, they generally pay back the cost in less than a decade of becoming operational and from then onward the cheap electricity generated without the negative environmental impact of coal/gas/oil fired power plants is a boon especially for a nation like Pakistan which is woefully short of power and cannot afford the high generation cost of fossil fuel driven power plants. Besides production of electricity, a multipurpose dam like the KBD provides water for irrigation. Pakistan has ample land that can be brought under cultivation provided fresh water is made available. Most of the southern half of the country receives scant rainfall – in fact much of the eastern portion of lower Sindh is classified as a desert. Water from River Indus is their only source for both agriculture and drinking purposes because majority of the province receives less than ten inches of rainfall annually and even access to ground water is difficult as it lies at a great depth and in most instances its salt content make it unfit for both drinking and agriculture. For the province of Sindh, a major dam like the KBD would be a boon as it would be a source for both affordable environmental friendly power and additional fresh water to bring further lands under cultivation that currently lie barren because of non-availability of fresh water.

Kalabagh Dam, experts estimate would cost around US dollar five billion and within five years it would have paid back its capital cost. The power produced by the dam would cost approximately around one third that of coal fired, one fourth of gas operated and one tenth of oil fired plants. In addition there will be no air pollution. Renewable energy sources like wind and solar powers are also environmental friendly but at today’s price they would be seven to twelve times respectively more expensive than hydel run systems.

According to Shams ul Mulk, KBD would make available about 10.36 Million Acre Feet (MAF) of which Sindh’s share has been planned at 4.75 MAF by IRSA.15 Munir Ghazanfar, however quotes WAPDA figures as a storage capacity of 6.1 MAF with the share of Sindh being 2.1 MAF.16 Even the lower figure should bring more land under cultivation and make up for the loss of land along the delta region because of sea incursion. Conversely, at the cost of bringing additional lands under cultivation, Sindh could allow some of the additional water to flow into the Arabian Sea to limit the damage to the mangroves and the Indus Delta.

As far as the Kachho is concerned, it is no secret that the wild growth there provides a safe haven for robbers and dacoits, many of whom operate under the protection of influential landlords in the region. The deforestation of Kachho lands would go a long way in improving the poor state of law and order there – and if the province still feels the Kachho forests must survive, part of the share from the KBD could be diverted towards the Kachho.

Technical Objections to the KBD Project

PPP members and parliamentarians from Sindh along with the nationalist parties of the province claim that the River Indus has already been dammed to its full capacity. The average river water flow of the past two decades show that any further damming can only be achieved at the expense of the 10 MAF of water which has been agreed upon by the Indus River System Authority (IRSA) accord of 1991 as the minimum flow down the Kotri Barrage, even in the average year of water availability.17 They reject the WAPDA study which indicates that after allowing for the 10 MAF flow downstream of Kotri Barrage, KBD storage on an average basis will be around 6.1 MAF18 according to Munir Ghazanfar and 10.32 MAF according to Shams ul Mulk.19 Munir Ghazanfar in his treatise Kalabagh Dam and its Water Debate in Pakistan has given sets of comprehensive and bewildering (for the layman) statistical data on the water availability in the Indus Basin, covering both the governmental study reports under WAPDA and independent ones by A.N.G. Kazi and Abbasi, specialists in the field from Sindh. The conclusion which may be drawn from his dissertation is that while the WAPDA figures appear to be optimistic, even if one accepts the reports by Kazi and Abbasi, on an average basis KBD will make available extra water for irrigation.

KBD critics point out that currently about 4 MAF filter through the three eastern rivers and in future this figure is likely to be reduced to a trickle when the Indian plan to consume all the water from these rivers reach fruition – there will just be no extra water left for further storage and KBD as a storage dam would become irrelevant. Assuming the three eastern rivers are completely bled dry by India in the near future, this will have very little impact on the Kalabagh storage potential as KBD site on River Indus is much before its confluence with Ravi and Sutlej. River Indus enroute to the KBD site is fed primarily by Gilgit, Swat, Chitral and Kabul rivers besides a number of streams and rivulets and none of them flow through the Indian territory. If the objection by the critics of no extra water availability in the Indus River System is to be accepted, they should also demand that the under construction Diamer Bhasha Dam upstream of Tarbela on River Indus should only be meant for power generation and not for storage. Accepting Diamer Bhasha Dam as a multipurpose dam would indicate that they themselves do not take the objection of unavailability of water for storage very seriously.

The fear of the opposition that KBD would contribute further to the already serious issue of water logging and salinity that afflicts Sindh is also unfounded. As has been explained earlier, dams do not cause water logging and salinity, canals do. If Sindh does not want any increase in this menace it could allow the extra water accruing from KBD to remain in the river, flood the Kachho and eventually flow down to the sea.

Should Sindh opt to forego bringing additional land under cultivation for fear of water logging or would it be wiser to undertake other measures that have proven effective in controlling the menace. Lining of the existing and fresh canals and water courses and better irrigation and farming practices where instead of flood irrigation technique, drip irrigation system is adopted will address the water logging and salinity threat to a large extent. The drip irrigation method is far more efficient use of sweet water for farming and if it is mandated and adopted as a matter of state policy, much more land can be made arable within the current amount of water availability. It is estimated that by adopting measures of water conservation and prevention of water wastage, as much if not more water that KBD would store can be saved. Even if KBD is built, adoption of more efficient water usage for irrigation and farming has become unavoidable if the nation wants to avoid further deterioration of the water starved condition it is already suffering from and aims to overcome the deficit.

Political and Psychological Objections to the Kalabagh Dam Project

Munir Ghazanfar has correctly concluded that the real basis for the resistance to KBD by Sindh boils down to a lack of trust. He states: “The federal government has repeatedly offered to incorporate Sindh’s water concerns in the Constitution. Since Sindhis have refused that offer, clearly there is a breach of trust.”20

Sindh politicians blame Punjab for their lack of trust. They complain that Punjab is perpetually guilty of violating the IRSA water sharing formula and cannot be trusted. In support of their assertion they cite the Chashma-Jhelum link canal which was to be opened only when excess water was available in the river but Punjab uses the canal even during the lean season.

When Shams ul Mulk was asked to comment on this accusation, he answered that yes, this violation did take place once in the past twenty years and since then the IRSA formula is being adhered to. It is unfair to mistrust an entire province for a single breach which has since been rectified.21 Munir Ghazanfar, however, maintains that the Chashma Right Bank Canal which was made on the promise that water will be drawn from it only during flood seasons is being fed on perennial basis.22 When questioned on the observation of Munir Ghazanfar, Dr. Shams ul Mulk responded that even if the statement of Ghazanfar is true, Punjab is only taking its due share from the link canal and not taking any share of Sindh which continues to receive 70% of water from the Tarbela reservoir. IRSA records will substantiate his statement, he asserted.23

On the charge of Sindh that their share of water agreed by IRSA is not being provided, Shams ul Mulk remarked that Sindh continues to blame Punjab for misappropriation of its water share in public and on talk-shows but wonders why it has never officially taken it up even once with the Council of Common Interest (CCI), which is the constitutionally mandated forum to resolve these issues. According to him, for the past twenty years on an average Sindh has been getting about 70% of water from the Tarbela Dam, while KPK receives a mere 4%. Any fresh debate in the CCI on the water distribution subject could result in a more equitable water sharing formula of Tarbela Dam – hence, according to him, Sindh is reluctant to approach the CCI to address their concern.24

On the psychological plane, the objection to KBD by the PPP and Sindhi nationalists could be traced to the proud and ancient history of the province. The very name of Sindh is derived from River Indus, which in local language is known as River Sindh. River Indus has always been historically revered as a gift of nature and a life-line that has allowed humanity to survive and flourish in a land where rainfall is scarce and inadequate – Sindhis genuinely believe they owe their very existence to the river. The IWT accord and the follow up dams in the Indus River Basin both in India and Pakistan has shrunk the once mighty river to a mere stream and any further damming must be resisted if the river is to be preserved from further deterioration. Protection of Sindh and its ancient heritage, therefore, takes precedence over Pakistan. While this stance may be justified for the Sindhi nationalist parties who make no bones about putting the interest of Sindh ahead of Pakistan, for the PPP, which has always claimed to be a national party, such an attitude belies its claim.

Distrust of Punjab by Sindh appears to be the central theme in its naked opposition to KBD. Munir Ghazanfar wryly observes:

“Why on earth then are the three provinces against the construction of the dam even when the land to be lost to submergence (24,500 acres) and the population to be displaced (48,000) is located mostly in the Punjab? The dam is going to neither submerge any land in Sindh or Balochistan nor displace any people. Yet, all the three provinces are dead set against the construction of the KBD. No wonder the media has highlighted the opponents of KBD as irrational, politicized and malicious. Only one explanation has been put forth for this apparent irrational attitude of the smaller provinces i.e. the three smaller provinces do not want Punjab to receive the royalties from power generation and that issue has been politicized and, therefore, not being decided on merit.”25

The dam itself and the release of water from the reservoir would also be under the control of Punjab which makes Sindh uncomfortable. About the Tarbela Dam which is based in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh has rarely raised such fears about its function. Diamer- Bhasha Dam currently under construction will also be outside the Punjab province hence Sindh has given its approval as a multipurpose dam despite claiming that there is not enough water left in the Indus Basin system for further storage.

Sindh’s fear of Punjab as the big brother which tends to bully the others is shared by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan where the latter despite having no axe to grind against KBD has also passed a resolution in their assembly rejecting the dam. Perhaps a division of Punjab into two by the creation of Seraiki Province in southern Punjab could lessen the Punjabi fear syndrome of the other three provinces in the federation. It could also ease the Sindhi anxiety about Punjab stealing their share of water as it would not find it easy to overcome the joint resistance of Sindh and Seraiki provinces.

Conclusion

That Kalabagh Dam has become highly controversial and politicised is obvious and it is equally true and evident that its construction would help alleviate the acute power and water shortage the country currently faces. The water storage and distribution of KBD may be controversial but the 3600 Megawatt of electricity that could be generated is beyond dispute – its power generation capability on its own would make the project worthwhile. The cost per kilowatt hour of as low as Rs. 1.54 may be challenged on the grounds that it does not factor in the capital cost, which is substantial. Even after including the capital cost, per unit price would still remain below Rs. 10 with no air pollution to boot. A multipurpose dam like the KBD is expected to pay back the investment in about five to six years and from then onward the cost of Rs. 1.54 per unit (at the current market rate) would apply as this would be sufficient to cover the operational and maintenance costs of the dam.

By its very location, a dam downstream of Tarbela Dam will enhance Tarbela’s power generation capacity without any additional investment. Since water for Kharif crop downstream of Tarbela is required from July onward, no water can be released from the Tarbela reservoir before July to run the power generators even when enough water is available in the reservoir for the purpose. After the Kalabagh Dam is commissioned, Tarbela can open its spillways to produce electricity before the start of the Kharif season and the water released instead of going down the Indus River into the Arabian Sea can then be restored in the KBD reservoir and discharged from July onward both to produce power and meet the Kharif season’s agricultural needs of Punjab and Sindh. The two dams working in tandem and in synergy will provide additional hydel power to the national grid at practically no extra cost.

The water distribution mechanism downstream of KBD is the one aspect that needs to be resolved among the provinces. Both Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh vociferously oppose the dam because they do not trust Punjab controlling the water tap at Kalabagh. Ironically, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa would be the biggest beneficiary of the Indus water if the multipurpose KBD project is made operational. The province currently has zero share of the Mangla Dam reservoir because of its geographical location and from Tarbela reservoir, which is within its territory, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s share is barely 4%.

The River Indus meanders through the D. I. Khan region of the province which lies west of the river bed before it enters Punjab. Unfortunately the arable lands of D. I. Khan is in the shape of a flat plateau around 50 -200 feet above the river. Since water cannot be delivered to these parched lands through gravity feed, the only way to provide water to them would be by pumping it up, which would raise the cost to above Rs. 5000 per acre – ten times more expensive than through gravity feed. With the KBD reservoir raising the level by up to 900 feet above ground level, canals emanating from there can easily provide gravity fed water to the entire water starved lands in D. I. Khan and Bannu divisions of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa should also remember that even after the completion of Diamer-Bhasha Dam the two divisions of D. I. Khan and Bannu would still be unable to receive even an inch of extra water and the same leaders who are presently opposing KBD would blame Punjab for stealing their share of water from the Indus River.

Of the total quantity of water that can be stored in the KBD reservoir, IRSA has earmarked 20% for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which according to Shams ul Mulk would amount to about 2MAF, or 1.22 MAF according to Munir Ghazanfar. For the water deficient province to oppose a project which would provide this amount of extra water is sheer lunacy. As a senior ANP leader had once stated to Dr. Shams ul Mulk: “even if you are giving us gold in the form of KBD, we are not the buyers.”26 If the people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa truly realise the tremendous cost they are paying for the policies of some of their leaders, they could well force them to review their rigid stance or be prepared to be routed in the next General Elections.

The reservations and fear of Sindh about being short-changed of their share of water from River Indus merit consideration but Sindh’s refusal to discuss their grievances at the appropriate forums, calling it a dead issue that can only be revived at the cost of national integrity, is simply unacceptable. Sindh’s apprehensions must be taken up at IRSA and the CCI and a resolution sought on the basis of logic and reason rather than emotions. The mantra that Kalabagh issue is dead and buried and not open to any further debate is totally unacceptable – the small feudal/political oligarchy must not be allowed to hold the entire nation hostage to their narrow selfish interests.

In a democratic federation like Pakistan, bulldozing of the KBD project without taking into confidence the general public in Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa would be counterproductive. During the floods of 2010, when the local Sindhis learned that a dam like the KBD can mitigate the fury of floodwaters and reduce the loss of life and property, many asked why the dam was not being constructed. When informed that their leaders from the PPP and the nationalist parties were preventing it they implored the federation to go ahead with the construction of the dam and if their leadership opposed it, they would reject them.

Public education about both the merits and demerits of a dam like the KBD is the need of the hour. Unfortunately both the supporters and those who oppose it tend to take extreme positions much like opposition lawyers who only want to promote their viewpoint. A realistic and balanced campaign can educate the public and when the people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh learn the truth about the Kalabagh Dam project, the very same politicians who scream blue murder at the very mention of the Kalabagh Dam will either fall in line or fall away.

Diamer-Bhasha Dam and various steps for water conservation and its more efficient usage are the need of the hour but by themselves they are no substitute for the Kalabagh Dam project. Pakistan is already water starved and way short of power and unless all necessary measures to generate power, store additional water and its conservation through more efficient usage are simultaneously incorporated, Pakistan would continue to struggle. As Dr. Shams ul Mulk lamented: “When I think of the Kalabagh site and I see no dam there, it is not only that I miss the enormous benefits the country could have obtained but I see the situation as a monument of triumph of falsehood over truth and reason.”27

There are credible reports about a visit to Dera Ismail Khan by Quaid-e-Azam way back in 1948 where the people of the area had managed to approach the Quaid and complain that since their land situated west of the River Indus was higher than the river bed, they could not utilise the river water for irrigation. The Quaid had then ordered the construction of a storage dam large and high enough at the current Kalabagh Dam site from which canals could be taken out to irrigate the lands west of River Indus in the Dera Ismail Khan region.28 This is one more of the Quaid’s dream and vision that the nation has yet to fulfill.

End Notes

1 River Beas originating from the province of Himachal Pradesh in India Join River Sutlej in the Indian province of East Punjab before the two enter the Pakistani territory as River Sutlej – hence Punjab which literally means the land of five rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi and Sutlej) is so named.

2 Interview Dr. Shams ul Mulk, ex-Chairman WAPDA, October 19, 2015.

3 As narrated by Dr. Shams ul Mulk. He had heard it from some key WAPDA officials, including ex-President Ghulam Ishaq Khan, who were a part of the IWT negotiation team and were a witness to this conversation, which for obvious reasons was never recorded officially.

4 Shams ul Mulk, the grievous betrayal, based on an article written for Hilal ISPR Rawalpindi

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

7 M. Suleman Khan, Kalabagh Dam per Ittefaq e rai zururi kyun, monthly Mustafai News, Karachi, July 2015, p 12

8 Op cit. interview Dr. Shams ul Mulk

9 Ibid

10 Ibid

11 Ibid

12 Name of the host and the senator withheld on request.

13 Op. cit. Interview Shams ul Mulk.

14 Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_dams_and_reservoirs_in_Pakista, accessed on November 6, 2015.

15 Shams ul Mulk, Facts and Fancies, Part – 1, May, 2013,

16 Munir Ghazanfar, Kalabagh Dam and the Water Debate in Pakistan, Lahore Journal of Policy Studies 2(1), September 2008, pp 154-155.

17 Ibid p 165

18 Ibid p 154

19 Shams ul Mulk, Fact and Fancies Part 1, (Revised on August 6, 2013.

20 Op cit. Munir Ghazanfar, p. 169

21 Op cit. Interview, Shams ul Mulk

22 Op cit, Munir Ghazanfar, p. 170

23 Op cit. Interview, Shams ul Mulk

24 Ibid

25 Op. cit. Munir Ghazanfar, p155.

26 Op. cit. Interview Dr. Shams ul Mulk

27 Ibid

28 Col Abdul Razzaq Bugti, Pakistan ki maashi tarraqi kay liay Kalabagh Dam ki taameer na guzeer hai, monthly Mustafai News Karachi, p 16