The Race towards Nuclearization

Pakistan’s quest for attaining nuclear weapons was solely driven by India. When ‘Buddha smiled’ in the Indian Pokhran in 1974, achieving nuclear weapons parity with its arch enemy for the beleaguered nation that had not yet fully recovered from the 1971 split became an obsession. There was across the board near unanimity among the country’s populace that without a matching nuclear response the perceived Indian threat to the national existence could not be countered.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto set the ball rolling by establishing an autonomous and powerful body tasked to build the bomb at any cost and/or by any means. His ouster in 1977 did not impede the progress towards nuclear weaponization and by 1985 under the much maligned Zia ul Haq Pakistan had eventually crossed the nuclear threshold – it had successfully put together and clandestinely cold-tested a nuclear weapon based on the highly enriched Uranium fuel. Delivery means, however, remained one dimensional and not very reliable.

The Bomb in the Basement

Possession of nuclear weapons was one thing, declaring it to the rest of the world was yet another matter. And here Pakistan was faced with one of the numerous paradoxes associated with the dynamics of nuclear deterrence. Publicly acknowledging the successful weaponization of the supposedly peaceful nuclear programme would have attracted heavy economic and political sanctions from the international community especially USA, that the country could ill afford especially at that point in time. And yet, unless its primary adversary India was unequivocally conveyed that it had the ‘bomb’, there would be no nuclear deterrence. India eventually provided the opportunity to resolve this quandary.

In December 1986 under the codename Exercise ‘Brasstacks’ the bulk of the Indian offensive formations along with the strike elements of the IAF were deployed right on southern border of Pakistan. From the Indian perspective this was a routine peacetime exercise but Pakistan sensed something sinister. The threatening exhibition of fully armed conventional forces right on the border and strategic intelligence gathered from other sources appeared to indicate that under the pretext of the exercise India was poised to launch a surprise major offensive in a sector considered Pakistan’s soft underbelly. Something had to be done quickly to deter the Indians from this misadventure.

An audacious military manoeuvre by Pakistan apparently put paid to any offensive design that Brasstacks might have had. The massive concentration of military formations in the exercise area had created a partial vacuum in parts of the Indian Held Kashmir. Pakistan mobilized and deployed its offensive formations in the Kashmir corridor poised to launch a major offensive should India open hostilities in the southern sector. Purely from the viewpoint of the balance of forces in the two sectors, the Pakistani offensive package was likely to achieve its military objectives earlier than the Indian one. In pure military jargon, Pakistan had the ‘superiority of strategic orientation’.

If the Indian military plan of a major land/air offensive to destabilize Pakistan is accepted, it would indicate that mere suspicion of the presence of nuclear weapons with Pakistan had failed to deter them. If the nuclear arsenal that the country had developed at a great cost and risk was to pay its peace dividend, it was important to convert the suspicion to near certainty by deliberately leaking key details about the nuclear programme that would in no uncertain terms convince India that the bomb really existed with Pakistan.

In a bold and which some might consider a reckless move in 1987, a very renowned and respected Indian journalist Kuldip Nayar was approached and covertly granted access to interview the controversial ‘father of the Pakistani bomb’ Dr. A. Q. Khan. He visited Pakistan on January 29, 1987i to conduct the interview and the good doctor apparently provided detailed information on Pakistan’s nuclear programme which left little doubt in the mind of the interviewer that Pakistan was in possession of nuclear weapons and had the necessary wherewithal and resolve to use it should India threaten its security.

Kuldip Nayar dropped this bombshell on his return to India when the scoop was published by the Observer a British newspaper on March 1, 1987ii It had the necessary impact and the message that Pakistan was now a nuclear weapons state finally sunk in. The government of Pakistan in the meanwhile debunked the interview as totally baseless and denied any weaponization programme. That Pakistan was a key US ally in the then ongoing war against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan helped stave off any serious international economic or political reprobation. The axe fell three years later when the service of Pakistan was no longer required by USA.

Indian military exercise Brasstacks eventually remained confined to their side of the border. While the Indians maintain that there never was any offensive design to begin with, Pakistan has no doubt that its own military response and Dr. A. Q. Khan’s planned leaks played the part in deterring India from the surprise attack. The nukes, according to them had provided its very first ‘peace dividend’ and it marked the beginning of the age of the ‘Bomb in the Basement’ phase between the two warring neighbours in the Indian subcontinent.

From 1987 to 1998 the ‘Bomb in the Basement’ policy was in play by both India and Pakistan. The period also witnessed an escalation in the number of bombs by both and the introduction of surface to surface ballistic missiles as the primary delivery means of the deadly cargo. Compared to the aircraft delivery mode, the missile based system enhanced the range by a considerable margin besides making their interception far more difficult – both the countries had to a large extent established the second strike capability against each other and had entered the phase of a smaller version of the Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) mode. There were a number of mini crises during the period which were eventually resolved without escalation to the use of the military force. The pro bomb lobby in the country credit it to the nuclear factor while the anti bomb ones would argue that sensible diplomacy avoided another war between the two belligerents.

Coming out of the Nuclear Closet

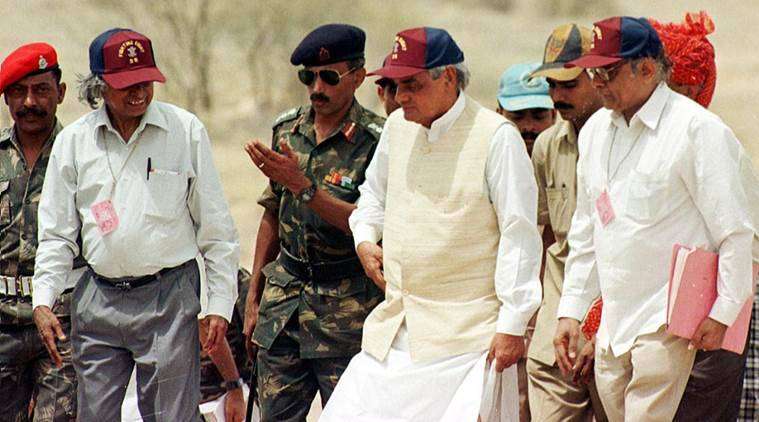

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led coalition formed the government in India following the 1998 General Elections and the nuclear stakes were raised when India detonated a series of nuclear devices on May 11, 1998 in Pokhran – India had finally come out of the nuclear closet and triumphantly announced its entry in the hitherto exclusive overt nuclear weapons club. A raging debate ensued in Pakistan whether it should follow suit and explode the bombs to prove to the world especially India that it did indeed possess nuclear devices. There was immense pressure from USA to prevent Pakistan from overtly demonstrating its nuclear might and both carrot and stick were abundantly employed.

The Pakistani public overwhelmingly supported a tit for tat response and only a handful of peaceniks advised against any such move. The anti bomb explosion lobby (labelled as nuclear doves or simply doves) argued that the nuclear deterrence will not add to the deterrence value that the Bomb in the Basement policy already provided, and by not detonating Pakistan would avoid the inevitable economic sanctions. Furthermore, they hoped by taking the high moral ground and not exploding Pakistan’s stature in the comity of nations would get a major boost. They also warned of a debilitating nuclear arms race if Pakistan followed the Indian lead, an arms race that would weaken its already impoverished economic state which could result in its disintegration, much as the Soviet Union had imploded by getting trapped into an arms race by the USA during the Cold War era.

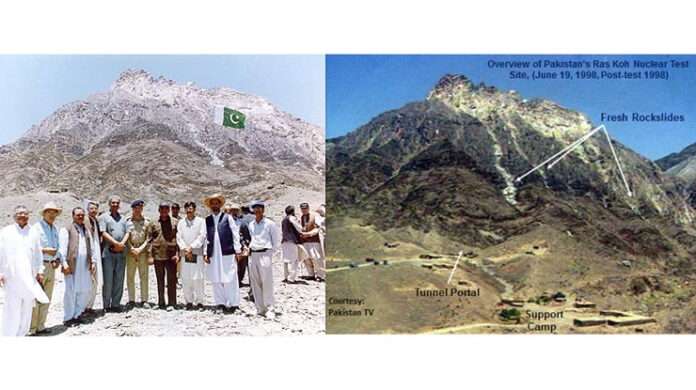

The pro bomb explosion lobby (aka nuclear hawks or simply hawks) also came up with some powerful arguments in support of the explosion. They maintained that without overtly demonstrating its nuclear weapons capability, the value of the Bomb in the Basement deterrence would simply evaporate. The Indian taunts about Pakistan bluffing regarding its nuclear arsenal during the debate further cemented their logic. Additionally they argued that a nuclear arms race could easily be avoided because the very massive destructive nature of these weapons makes it possible to establish a very potent deterrence by maintaining just a handful of deliverable weapons, regardless of the size and power of the adversary’s nuclear arsenal. And finally according to them a demonstrated nuclear weapons capability would in the long run allow Pakistan the luxury of not having to match the Indian growing conventional forces and could even permit trimming it down further, much like nuclear France and Britain have done post World War II. The hawks won hands down in the end and Pakistan exploded a series of nuclear devices on May 28, 1998.

The 1998 Kargil conflict was the first and so far the only limited military clash between the two belligerents following their overt entry in the nuclear weapons club. The hawks and doves have derived very different lessons from the event. The former claim that the nukes averted another India – Pakistan war of the 1965 and 1971 mould while the latter maintain that sans nuclear weapons there would have been no Kargil. There are elements of truth in both the assertions.

In hindsight it is clear that the nuclear factor did play an important role in keeping the conflict confined but not in the manner the hawks suggest. From 1948 to 1971, India and Pakistan were non-nuclear states and they fought three major wars during the period. In all the three instances even when the situation had reached a boiling point and an armed conflict was imminent, the world body led by the two superpowers merely expressed their concern but did not directly intervene to diffuse the crisis. In 1998, it recognised that if the Kargil Conflict spilled across the international borders it could easily lead to a nuclear holocaust that would severely damage the world ecology. This was too big a risk to ignore.

The world led by the sole super power USA first convinced India to avoid escalation across the international border or even the LOC. It followed up by putting Pakistan, which was considered the aggressor under immense pressure to withdraw the contingent which had infiltrated and occupied the Kargil heights. Pakistan eventually had to comply and a potential nuclear showdown in the region was averted. The world body very likely would not have reacted with the same urgency if the nuclear factor was not in play. The presence of nuclear weapons in effect favoured India, even if did prevent Kargil from turning into an all out war between the two nuclear armed neighbours.

On the other hand it can also be argued that the absence of the nuclear factor would have strongly discouraged Pakistan from launching the Kargil misadventure to begin with. Minus the nuclear deterrence a military assault across the international border similar to the 1965 model would have been the most likely Indian response to Kargil, which Pakistan was neither prepared for nor in a position to withstand. Kargil operations from the Pakistani viewpoint then would have been a non-starter.

From 1998 to the present, India and Pakistan have stumbled into a series of crises where an armed conflict appeared imminent but every time they have managed to pull back from the brink. The first was in 2001 when the Indian parliament came under attack by a group which it believed was launched by the Pakistani intelligence agency, the ISI. Pakistan vehemently denied any such link. India mobilized its armed forces for a major offensive in Pakistan and the latter also went on full defence alert and the two forces remained eyeball to eyeball for over six months. A combination of world intervention, Pakistan’s strong conventional defence posture and its oblique nuclear escalation threat eventually diffused the situation. Unlike the Kargil episode on this occasion the world pressure to de-escalate was much more on India than Pakistan.

In 2008 Mumbai, the Indian financial capital came under attack by a group having links to the Pakistani soil. Tensions rose to a very high level but it did not result in troop deployment by either side. The nuclear factor and foreign intervention finally helped in diffusing the crisis. Again since 2011 the two continue to trade accusations of conducting proxy war on each other through terror raids. Pakistan says it has solid proof of India abetting and financing the Baloch rebels and the TTP while the Indians blame the Pakistani ISI for masterminding a number of terror attacks inside Afghanistan, specifically the one that attacked and damaged the Indian Embassy in Kabul. Besides trading barbs and firing across the LOC in Kashmir that has risen in intensity ever since the Modi government has assumed power the uneasy peace between the two nuclear armed warring nations has held so far.

Nuclear Balance Sheet for Pakistan

2015 marks the completion of three decades since Pakistan acquired the indigenous capability to build a nuclear arsenal. This is a fairly long period to make an objective assessment of the positive and negative aspects that has accrued as a result of becoming a nuclear weapons state. The three major planks on which the hawks had successfully built their case in favour of the bomb explosion will be examined and these are: the deterrence value of the bomb; the avoidance of a nuclear arms race if Pakistan becomes an overt nuclear nation; the liberty to cut down on the conventional forces once nuclear deterrence was in place.

On the first point, the Kargil skirmish aside, India and Pakistan have avoided a military confrontation despite the two belligerents periodically accusing each other of grave provocations. Even the Kargil crisis remained confined and unlike 1965 did not widen into an all out war. The nuclear factor did play its role and one can conclude it has come good on this count and to date has delivered the peace dividend as envisaged by the hawks.

On the question of a nuclear arms race the hawks got it wrong while the fear of the doves has come true. The assumption that the race could be avoided might have worked in a utopian society but in the real world if the stronger side continues to increase its nuclear stockpile both in quantity and quality, the other invariably follows suit – a nuclear arms race then becomes inevitable. This phenomenon was seen during the Cold War era which eventually led to the demise of the Soviet Union and in the India – Pakistan scenario, a similar trend is being witnessed. Currently the size, quality and delivery means of the nuclear arsenal by both has the capability of destroying each other repeatedly and the nuclear arms race is a sad reality.

On the subject of reduction of conventional forces once nuclear deterrence is established, the hawks have again been proven wrong – the reduction of conventional forces on either side of the divide has not happened so far and is not likely in the near future. To the contrary, as the doves had feared, despite a sizeable nuclear armoury the conventional forces of both India and Pakistan have risen in number and cost. The nuclear weapons so far have put an even heavier defence burden on their respective national economies. UK and France could afford the luxury of reducing their conventional forces once nuclear deterrence was in place because they operate under a very different environment when compared to India and Pakistan. They have no unresolved land disputes with their neighbours and have the powerful NATO backup should any military threat materialize. Israel would be a more appropriate example and here despite a very large and potent covert nuclear arsenal, their conventional forces have continued to expand in size and capability.

To comprehend the working mechanism of nuclear deterrence another of its paradox needs to be understood. Unlike conventional arms that can be safely employed during war, nuclear weapons sole purpose is to deter the other side from military aggression; it cannot be used especially against another nuclear weapons state unless the nation as a whole has prepared itself to commit Harakiri. The weapon’s deterrence value is based on the assumption that even the slimmest chance of the threat of employment of these extremely destructive weapons materializing, would deter a potential aggressor. As the French General Andre Beaufre states: nuclear deterrence lies not in the actual employment of nuclear weapons but simply in the utilization of their threat.iii He further emphasises that the role of nuclear weapons is not to make war but to prevent it.iv

A shortcoming of the deterrence value of strategic (high yield) nuclear weapons was succinctly outlined out by General Andre Beaufre when he observed that the more stable the nuclear deterrence, the greater room it provides the other side to wage a war below the perceived nuclear threshold. The strategic nuclear weapons in his judgment only deterred full scale all-out wars and not the limited ones. When a stable nuclear deterrence is in place and the nuclear threshold is considered to be high, it might provide enough room and temptation to either of the antagonists to engage in limited intensity conflicts or even proxy wars.

The wily General observed that the mere induction of the tactical (miniature and low yield) nuclear weapons in the conventional battlefield as an integral part of the nation’s overall defensive response would extend the nuclear deterrence to even limited conflicts.v His analysis was based on the observation that in a number of war games where tactical nuclear weapons were employed, these eventually led to a full-scale nuclear exchange.vi Even limited conflicts, he postulated, can be deterred if the nuclear and conventional levels are firmly linked by the threat of employment of tactical nuclear weapons in a conventional battle.vii This would lower the nuclear threshold substantially and only by paying this price – and accepting the risk – he appears to argue, can nuclear deterrence be made effective across the full spectrum of armed conflict.viii

Pakistan apparently has embraced the Andre Beaufre doctrine when in 2013 it formally demonstrated the firing of the short-range Surface to Surface Missile Hatf 9 (Nasr) that can be armed with tactical nuclear warheads.ix It further announced that these nuclear tipped missiles would form an integral part of the defensive strategy as a counter to the Indian Cold Start and Pro Active Operations (PAO)x concepts.xi With this new radical step a case can be made where Pakistan should be able to exercise the option of a sizeable reduction in its conventional forces. There is, however, a major obstacle which prevents the country from doing so at this point in time.

Pakistan is currently facing a two-front threat scenario where it is actively engaged in a full scale prolonged subconventional war with powerful non-state actors with global links who have taken up arms against the state on its western border while it has to maintain a strong defensive posture against a potential potent threat on its eastern front. The Pakistan armed forces, especially the Pakistan Army is already overstretched. Besides carrying out major combat operations in its Tribal Belt – the stronghold of the militants – it is also actively involved in security operations across the country because the rebels have infiltrated the towns and cities and have embroiled the state in Urban Warfare. Under such strenuous conditions, reduction of conventional forces would be unwise, even suicidal. Once the western threat is neutralised and the border stabilized, the size and composition of the present conventional military setup could be re-examined. It might lead to a reduction in number but given the sophisticated and expensive modern military hardware required for war fighting, not necessarily in cost.

Nuclear and conventional deterrence work in tandem and a balance has to be maintained depending on the threat scenario. Nuclear deterrence by itself may not permit a reduction of conventional forces. For Pakistan these can only be scaled down once the threat matrix from India is sufficiently lowered by mutually negotiated resolution and settlement of major outstanding disputes.

Has the nuclear bombs fulfilled the peace and economic dividends as promised by the hawks and have the pitfalls that the doves had warned against been avoided. As the analyses indicate, the bomb has delivered on the first count but on the subjects of avoidance of an arms race and eventual lowering of the defence budget, it has failed so far.

The answer to the million dollar question whether the decision to become an overt nuclear weapons state has been beneficial or harmful will depend on one’s initial orientation: the hawks would give it a resounding thumbs up while the doves would consider it a potential disaster which was best avoided. Given that the hawks in the country far outnumber the doves, May 28 has been declared a national day and is celebrated by the entire nation every year as the Yom e Takbir (the day of greatness).

Endnotes

ihttp://www.telegraphindia.com/1071104/asp/7days/story_8508991.asp accessed on 30 January 2015

iiIbid

iiiAndre Beaufre, Deterrence and Strategy, translated from French by Major General R. H. Barry, New York and London, Frederick A. Praeger 1966, p 88

ivIbid p 103

vFor those unfamiliar with the nuclear lexicon, strategic (high yield) nuclear weapons are used against counterforce targets (population and industrial centres in this case) while the tactical (low yield) ones are meant for countervalue targets (military forces).

viOp. Cit. Andre Beaufre p 55. Also see Gavin J. Francis, the myth of Flexible Response, LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas, Austin, pp 14-15.

viiIbid. Also see Andre Beaufre, an Introduction to Strategy, translated from French by Major General R. H. Barry, Faber and Faber, 24 Russell Square, London, Chapter 3, p 88

viiiIbid page 55

ixhttps://www.pakistanarmy.gov.pk/awpreview/pDetails.aspx?pType =PressRelease&pID=131 accessed on 12 February 2015 and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasr_%28missile%29 accessed on 12 February 2015

xCold Start and PAO are war waging concepts which the Indian military planners have come up with as a counter to the nuclear deterrence of the Pakistani strategic nuclear weapons. Should the need to militarily punish Pakistan arise, the Indian Armed forces can engage Pakistan in a sharp and short war with limited political objectives while staying below their nuclear threshold employing the Cold Start or PAO strategies. According to the Indian military analysts, the Indian military publicly denies the existence of any such doctrines.

xiThe Express Tribune, Pakistan Army to Preempt India’s Cold Start Doctrine, 16 June 2013 accessed from http://tribune.com.pk/story/564136/pakistan-army-to-preempt-indias-cold-start-doctrine/ on 12 February 2015. (http://defenceforumindia.com/forum/pakistan/51976-azm-e-nau-4-a.html) accessed on 12 February 2015